DOI 10.1515/cllt-2013-0009

Corpus Linguistics and Ling. Theory 2013; 9(1): 1 – 38

Philip Durrant

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language:

the case of Turkish

Abstract: This study examines the extent to which complex inflectional patterns found in Turkish, a language with a rich agglutinating morphology, can be de-scribed as formulaic. It is found that many prototypically formulaic phenomena previously attested at the multi-word level in English – frequent co-occurrence of specific elements, fixed ‘bundles’ of elements, and associations between lexis and grammar – also play an important role at the morphological level in Turkish. It is argued that current psycholinguistic models of agglutinative morphology need to be complexified to incorporate such patterns. Conclusions are also drawn for the practice of Turkish as a Foreign Language teaching and for the methodol-ogy of Turkish corpus linguistics.

Keywords: formulaic language, collocation, collostruction, lexical bundles, usage-based model, Turkish, morphology

Philip Durrant: Graduate School of Education, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey E-mail: durrant.phil@googlemail.com

1 Introduction

The study of formulaic language is based around the insight that some linguistic sequences which could potentially be analyzed into smaller units are, for one reason or another, better treated as wholes (Durrant & Mathews-Aydınlı, 2011). In some cases, sequences need to be treated as wholes because their meaning or syntactic behaviour is not predictable from a more general knowledge of the lan-guage. Examples include idioms (e.g. the last straw), opaque collocations (e.g. French windows), and the ‘formal idioms’ discussed within construction gram-mar (e.g. the –er the –er) (Fillmore, Kay, & O’Connor, 1988). In other cases, se-quences are treated as wholes because, although they are semantically and syn-tactically regular, they have been accepted by the speech community as the usual way of expressing a particular message. Examples include phrases which have become linked to particular contexts (e.g. long live the king; as shown in Table . . .) and transparent collocations (e.g. answer the phone; commit a crime). Because the adoption of one form rather than another is largely arbitrary, nativelike production

2

Philip Durrant

requires specific knowledge of such forms (Pawley & Syder, 1983). Finally, a se-quence may be considered a formula if it occurs so frequently that some form of independent storage in long-term memory is cognitively more efficient than creat-ing the sequence from scratch each time it is needed (Goldberg, 2006, p. 64).

The study of formulaicity is closely associated with usage-based models of language (Kemmer & Barlow, 2000). According to such models, a speaker’s guage system is intimately bound up with their lifetime’s experience of the lan-guage. This is perhaps most prominently seen in the strong relationships which are held to exist between the frequencies of occurrence of various aspects of the language and their representation and processing by native speakers. Ellis (2002, 2008) has documented these relationships at length, showing how implicit learn-ing mechanisms ‘tune’ the language system, creatlearn-ing sensitivity to frequency of occurrence across all linguistic levels. The psycholinguistic evidence reviewed by Ellis shows frequency to affect the processing of phonology, phonotactics, read-ing, spellread-ing, lexis, morphosyntax, formulaic language, language comprehen-sion, grammaticality, sentence production, and syntax.

According to usage-based models, formulaicity can emerge in various ways (Ellis, 2003): through regular association between particular complex forms and particular contexts, leading to those forms’ entrenchment as formulaic items; through regular co-occurrence of words (or other linguistic units), leading to their mutual association, and hence status as collocations which have psychological reality for native speakers; and through the grammar learning process, in which even the most general syntactic representations emerge only from a gradual pro-cess of abstraction from lexically-specific exemplars, and never entirely lose their association with those concrete forms (Kemmer & Barlow, 2000, p. ix). On this view, the dichotomy between abstract syntax and concrete vocabulary – or be-tween rules and lists – is considered to be a false one. There is, rather, a continuum between wholly memorized and wholly rule-based constructions, with most forms falling somewhere between these extremes (Langacker, 1987). Hence, ap-parently abstract syntactic constructions may be associated with particular lexis (Hoey, 2005; Hunston & Francis, 2000; Stefanowitsch & Gries, 2003) and appar-ently memorized forms (such as idioms) may be subject to syntactic processing and variation (Gibbs, Nayak, & Cutting, 1989; Peterson, Burgess, Dell, & Eber-hard, 2001).

The formulaic perspective on language has provided important insights in a wide range of areas, including theoretical linguistics, psycholinguistics, corpus linguistics, second language learning, and natural language processing (see Wray, 2008 for a recent overview). A weakness of work in this area at present, however, is its focus on a rather narrow range of, usually European, languages, and especially on English. This has meant both that the benefits of taking a

for-Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

3 mulaic approach to language have been restricted to these languages and that the status of formulaicity as a general principle of language (rather than a quirk of a few selected languages) remains insufficiently firmly established. It is therefore important that formulaic language research be broadened to a wider range of languages.

As Biber (2009) has recently noted, a particularly interesting area for explora-tion is that of agglutinating languages, such as Turkish and Finnish, which make use of extensive systems of suffixes to build up complex word forms. The study of formulaicity in such languages is interestingly different from that in English in that their rich morphology raises the possibility that complex types of formulaic-ity may take place within, as well as between, formulaic words. Definitions of formulaicity have long acknowledged that formulaic language can include lin-guistic units at all levels (e.g., Wray, 2002, p. 9), and there is a rich psycholinguis-tic literature on the respective roles of memory and rules in the processing of morphologically complex words (see, for example, the papers in Baayen & Schreuder, 2003). However, there has been little consideration of how morpho-logical formulaicity might function in agglutinating languages. While some work has been done on the holistic processing of morphologically complex words in Finnish (Section 2, below), we shall see that these studies have adopted a rather simple dualistic model on which words are either stored as a fixed wholes or pro-cessed morpheme-by-morpheme. I will argue that, given the complexity of mor-phology in agglutinating languages, such an all-or-nothing dichotomy may be too simple to capture the full range of formulaic morphology in such languages. For-mulaic morphology, I will claim, is likely to include patterns falling between the extremes of full-form storage and full morphemic processing. Hypotheses about the types of formulaic patterns which might exist within morphologically complex words cannot be based on psycholinguistic data alone; they will require detailed corpus-based descriptions of the repeated patterns found in such languages.

The primary aim of the present paper is to provide an initial description of such patterns for Turkish. In particular, it will consider the extent to which three widely-researched formulaic phenomena – syntagmatic association between items (as in collocation), fixed sequences of items (as in lexical bundles), and associations between particular lexical and grammatical forms (as in collo-struction) – are demonstrated at the morphological level in Turkish. Each of these types of formulaicity offers a distinct, but incomplete, viewpoint on the repetitive patterning which exists in a language. Since these categories of formula were developed in the contexts of other languages, they may, ultimately, not be the best approaches to capturing Turkish formulaicity. However, it will be seen that the combination of the distinct viewpoints offered by each phenomenon both allows an evaluation of competing models of morphology and gives pointers

4

Philip Durrant

to ways in which the study of formulaic patterning in Turkish morphology might be further developed.

As well as extending our knowledge of formulaic language in general, and Turkish morphology in particular, studying formulaic morphology in Turkish will also, it is hoped, have more applied benefits. Descriptions of formulaic phe-nomena in English have provided important bases for applications such as dic-tionary writing, language pedagogy, and natural language processing, as well as serving as a foundation for the development of many corpus-linguistic method-ologies. It is hoped that a description of formulaicity in Turkish may provide sim-ilar benefits for that language. This is especially important at the present mo-ment in time, as corpus-based work in the language seems likely to accelerate rapidly in the coming years, with the recent release of the first Turkish National Corpus (www.tnc.org.tr).

2 Formulaicity in agglutinating languages

Turkish, like Hungarian and Finnish, is an agglutinating language, building up sometimes extremely complex word forms through an extensive range of suffixes. Though the distinction can be a problematic one (Beard, 1998), grammars tradi-tionally divide Turkish suffixes into the derivational and the inflectional. Deriva-tion is defined as “the creaDeriva-tion of a new lexical item (i.e. a word form which would be found in a dictionary)” (Göksel & Kerslake, 2005, p. 52). Attaching a deriva-tional suffix to a word creates a new word related in meaning to its stem, though the transparency of the connection between stem and word is variable. While a few derivational suffixes are still ‘productive’, in that they have a regular mean-ing and can be used with any stems fitting certain criteria, the majority are unproductive – i.e. they can be discerned within already existing words but native speakers no longer perceive them as available for use in the production of new words (Göksel & Kerslake, 2005, p. 52). Inflectional suffixes, on the other hand, are perceived as productive. Their primary functions are to indicate the relations between sentence constituents and to mark functional relations such as case, person, and tense (Göksel & Kerslake, 2005, p. 68).

We can take as a simple example of inflection the word olabileceğini (attested 18 times in newspaper corpus described below), which is found in contexts such as:

(1a) kasetin doğru olabileceğini düşünüyor

cassette-GEN genuine be-POSS-SUB-POS.3-ACC think-PROG.3 believe(s) that the cassette may be genuine

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

5 This word comprises the root form ol (‘be’) and four suffixes:

(1b) ol POSS-<y>Abil SUB-AcAK POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I root suffix 1 suffix 2 suffix 3 suffix 4

The notation used here indicates both the function and the phonemic form of the suffix (see Appendix for a full list of suffixes and their functions). The first suf-fix indicates possibility, the second indicates subordination through nominaliza-tion, the third indicates third person singular possession and the forth shows that the form is in the accusative case. It should be noted that Turkish morphemes are subject to a number of regular phonemic rules which can alter their phonological realisations. In the notation used here, and throughout the present paper, angled brackets indicate that a letter is included only if the suffix is adjacent to a vowel, while capitalisation indicates that a letter changes according to context, for example to ensure vowel harmony. In the present example, the As in suffixes 1 and 2 become Es and the K in suffix 2 is softened to Ğ.

There has to date been little investigation of the role of formulaicity in Turkish. Tannen and Öztürk (1989) and Doğançay (1990) describe the use and extent of situational formulas in conversation, and report such formulas to be extremely common. A few studies have also investigated collocation in Turkish: Oflazer et al. (2004) discuss how an automated corpus parser might handle multi-word expressions, Özkan (2007) draws on a corpus of literary works to identify and describe verb-adverb collocations, while Pilten (2008) uses a historical corpus to identify how the collocations of words within a certain semantic set have devel-oped over time. Doğruöz and Backus (2009) consider how Turkish as it is spoken by immigrants in the Netherlands is affected by Dutch formulas. However, none of these studies has addressed the key issue of formulaic patterns in morphology.

The most thorough investigation to date of formulaic phenomena in aggluti-nating morphology is found in the psycholinguistic literature on the processing of complex words in Finnish. Studies employing a wide range of methodologies (e.g, Lehtonen, et al., 2007; Lehtonen & Laine, 2003; Niemi, Laine, & Tuomainen, 1994; Soveri, Lehtonen, & Laine, 2007; Vartiainen, et al., 2009) have suggested a model on which most inflected nouns are processed morpheme-by-morpheme in both comprehension and production. This is revealed by consistently slower reaction times in lexical decision and naming tasks for inflected than for matched monomorphemic words, by the greater difficulties experienced by an aphasic patient in reading aloud inflected forms, by the same aphasic’s errors in produc-ing multimorphemic forms, and by evidence from magnetoencephalography of stronger and longer-lasting activation of the left superior temporal cortex when processing inflected forms. Very high-frequency inflected nouns were immune to

6

Philip Durrant

all of these effects, suggesting that such forms are holistically stored. However, it is notable that the frequency level at which holistic storage seems to occur in Finnish is much higher than that previously found for English. Whereas Alegre and Gordon (1999) found evidence for holistic processing in inflected forms with frequencies of around 6/million words, similar effects are seen in Finnish only at frequencies of around 100/million (Soveri, et al., 2007). It may be therefore that holistic storage is rarer in agglutinating languages than in languages with less rich morphologies.

While these studies provide a large amount of important evidence, one potential shortcoming is that they work within a dualistic paradigm, on which complex words are held to be either stored whole or fully processed. This model is at odds with usage-based models’ rejection of the dichotomy between lexis and syntax, and two different strands of research suggest that it may be too simplistic to capture the full extent of formulaicity. Firstly, within studies of formulaic lan-guage, corpus evidence suggests that formulas rarely consist of fully fixed strings. There is, rather, a predominance of partially-fixed sequences and probabilistic associations between linguistic units (e.g., Biber, 2009; Cheng, Greaves, & War-ren, 2006; Moon, 1998; Sinclair, 2004). Psycholinguistic studies of idiom process-ing have shown that this flexibility within formulaic sequences is reflected in pro-cessing, with the moveable semantic sub-parts of idioms playing an important role in their processing (Gibbs, et al., 1989).

The other strand of research which suggests that a whole-word vs. morpheme dichotomy may be too simplistic comes from connectionist models of morphology. According to such models, the psychologically-real components of words emerge from a language user’s input on the basis of overlaps between the words they encounter. Thus, a word-part such as past tense -ed is psychologically real only to the extent that it receives analogical support from its appearance across a range of words. Research in this tradition has shown that partial matches between words, which include not only word parts which are themselves words (e.g. the walk in walked) and traditional morphemes (e.g. the ject in inject and the ed in walked) but also phonaesthemes (e.g. the fl in ‘liquid’ words, such as flow, float, flood) can prime words with overlapping forms and meanings (Hay & Baayen, 2005).

Both of these lines of research suggest that a model on which the only alter-native to full morpheme processing is whole word retrieval may be too blunt to reflect the true nature of formulaic morphology. In order to develop more fine-grained models of what might be formulaic in agglutinating morphology, it will be necessary to provide a thorough corpus-based description of the repetitive pat-terns of morphology in agglutinating languages. The primary aim of the present paper is to provide an initial description of such patterning in Turkish.

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

7

3 Methodology

3.1 Corpus

Following researchers in the Firthian tradition (e.g., Hoey, 2005; Sinclair, 2004; Stubbs, 1996), formulaicity is defined here in terms of high frequency of occur-rence in a corpus. High-frequency forms are of interest in themselves in terms of what they can tell us about the nature of discourse (as discussed, for example, in the work of Stubbs (1996) and Biber and his colleagues (Biber, Conrad, & Cortes, 2004; Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad, & Finegan, 1999)). However, the central focus of the present study – like that of Hoey (2005) – is on the hypotheses that high-frequency patterns can suggest regarding the nature of psycholinguistic pro-cessing and representation.

As with Hoey’s work, the inference from corpus to mind relies on two key assumptions. The first is the usage-based principle that the frequency with which features of the language are experienced in input influences the representation of those features in the language system. The weight of psycholinguistic evidence in this area (see, e.g., Ellis, 2002, 2008) makes this assumption look plausible. How-ever, it should be borne in mind that links between frequency and representation are complex and affected by a variety of other factors (Ellis & Larsen-Freeman, 2006). Frequency-based hypotheses about the likely psycholinguistic realisation of any patterns found must therefore be read as exploratory and provisional. Pro-vided this caveat is kept in mind, though, corpus analysis of this sort has the potential to open up new avenues of psycholinguistic research whose potential may not become clear from online studies alone.

The second key assumption is that the corpus investigated is representative of the input experienced by language users. Unfortunately, this assumption is often an unjustified one. Corpora are usually intended as balanced samples of texts from across a particular language domain, whether that domain be a national variety (e.g. British National Corpus, Corpus of Contemporary American English, METU Turkish corpus) or a more specialised field of discourse (e.g. Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English, British Academic Written Corpus). While such corpora are excellent for some purposes, none of them resemble any language user’s likely experience with the language: no one will be exposed to the full range of different styles present in the British National Corpus or to the range of academic topics and genres covered by the Michigan Corpus (Hoey, 2005, p. 14).

This mismatch between the range of texts usually found in corpora and what a language user actually experiences is a serious shortcoming of previous work in

8

Philip Durrant

this area. This is acknowledged by Hoey (2005), who emphasises that his research into lexical priming is not able to indicate the primings of any particular language user. However, he maintains that corpora can indicate “the kinds of data a lan-guage user might encounter” and so suggest “the ways in which priming might occur and the kinds of feature for which words or word sequences might be primed” (Hoey, 2005, p. 14). No argument is presented for this claim, however, and it is not clear what Hoey’s optimism is based on. There is every reason to be-lieve that the highly skewed language exposure which is likely to be typical of most language users is radically different from that which is found in balanced corpora. Discourse analysts would be rightly distrustful of any research which tried to draw conclusions about ‘academic language’ based on a corpus of one individual’s exposure to the domain. We should be equally suspicious of research drawing conclusions about individuals’ exposure based on broadly representa-tive cor pora. This point is especially important in research on formulaic language, where the natural skew inherent in an individual’s experience with the language is likely to be an important factor in increasing the formulaicity of their input (c.f., Goldberg, 2006).

With this in mind, the current study does not draw on existing large-scale corpora of Turkish. It uses instead a corpus representing one language user’s (the present author’s) exposure to a single discourse type (online newspapers) in Turkish over a period of 6 months. Like many foreign/second language learners, my main source of extensive reading in my target language is online newspapers. Between November 20, 2009 and May 20, 2010, I stored everything I read in this form as text files, and collated these files to create the corpus. Over the six-month period, I read on a total of 111 days (usually reading on five days each week) and for a mean of 50 minutes per day. In total, I read 765 texts, or part texts1 – 515 news

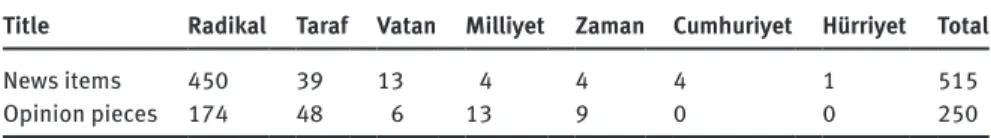

items and 250 opinion pieces – totalling 374,590 words. Though these texts were taken from 7 different newspapers, the vast majority were taken from a single title. Table 1 shows the total number of texts of each type taken from each newspaper.

1 Only those parts of the text which I actually read were recorded.

Table 1: Contents of the newspaper corpus (numbers of articles per publication)

Title Radikal Taraf Vatan Milliyet Zaman Cumhuriyet Hürriyet Total

News items 450 39 13 4 4 4 1 515

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

9 Clearly, given the nature of the corpus, the degree to which specific patterns found can be generalised to other language users and other text types is an em-pirical question, open to further investigation. What we can say, however, is that, given such experience, these patterns are likely to be real for this particular reader with regard to this particular discourse type. Moreover, if we make the highly plausible assumption that this reader’s experience is at least analogous to that of other language users, the types of frequency-based biases seen here are likely to be typical of any individual user’s input.

3.2 Procedure

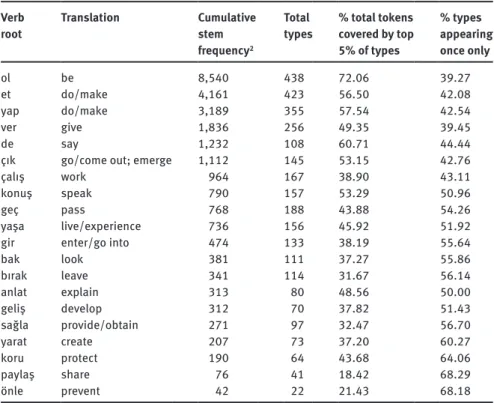

Whereas work on suffixation in Finnish has focused on suffixes following nouns, the present research will look instead at those following verbs since the latter comprises a much more extensive morphological set and so a richer database for study. Twenty verbs will be analysed. It seems likely a priori that formulaicity will be more prominent in higher than in lower frequency verbs. Verbs were therefore selected to cover a wide range of different frequencies. The verbs, their English translations, and their frequencies in the corpus are shown Table 2.

All inflected forms of these verbs were retrieved from the corpus using an alphabetical word list generated by WordSmith Tools (Scott, 2008) and each form was manually coded for inflectional suffixes. This coding was based on the list of inflectional suffixes provided by Göksel and Kerslake (2005). All suffixes identi-fied with these verbs are shown with their frequencies in the corpus and brief characterisations of their functions in the Appendix.

Two important points should be noted here. First, the analysis considers only inflectional morphemes. This focus was chosen because inflectional forms are considered to be, on the whole, actively productive. The question of formulaicity is, therefore, more open than for derivations, which, as we have seen, are consid-ered to be largely unproductive (though it is worth noting that the Finnish mor-phology studies suggest that derived forms are holistically stored in the input lexicon only, with morpheme-based processing employed in production (Laine, Niemi, Koivuselkä-Sallinen, Ahlsén, & Hynönä, 1994)). Second, some distinct morphemes in Turkish are orthographically indistinguishable from each other. For example, the subordinator SUB-<y>AcAK is identical to the future tense marker FUT-<y>AcAK. In such cases, concordance lines were consulted to deter-mine the frequency of each morpheme.

All inflected forms of the twenty verbs under investigation were listed in a spreadsheet, along with their frequencies of occurrence, with each column in the spreadsheet representing one suffix. Table 3 illustrates the contents of the

10

Philip Durrant Table 2: Verb stems studied Verb

root Translation Cumulative stem frequency2

Total

types % total tokens covered by top 5% of types % types appearing once only ol be 8,540 438 72.06 39.27 et do/make 4,161 423 56.50 42.08 yap do/make 3,189 355 57.54 42.54 ver give 1,836 256 49.35 39.45 de say 1,232 108 60.71 44.44

çık go/come out; emerge 1,112 145 53.15 42.76

çalış work 964 167 38.90 43.11

konuş speak 790 157 53.29 50.96

geç pass 768 188 43.88 54.26

yaşa live/experience 736 156 45.92 51.92

gir enter/go into 474 133 38.19 55.64

bak look 381 111 37.27 55.86 bırak leave 341 114 31.67 56.14 anlat explain 313 80 48.56 50.00 geliş develop 312 70 37.82 51.43 sağla provide/obtain 271 97 32.47 56.70 yarat create 207 73 37.20 60.27 koru protect 190 64 43.68 64.06 paylaş share 76 41 18.42 68.29 önle prevent 42 22 21.43 68.18

2 In this paper, the term ‘cumulative stem frequency’ is used to refer to the combined frequency of all inflected forms of a verb.

Table 3: Sample analysis

Word Freq. Root Suffix 1 Suffix 2 Suffix 3

Anlatmaması 1 anlat NEG-mA SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> Anlatmıyor 1 anlat NEG-mA IMP-<I>yor

Anlatmadım 1 anlat NEG-mA PRF-DI 1-m

Anlatın 3 anlat 2PL-<y>In

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

11 spreadsheet. This spreadsheet formed the database for all of the analyses which follow. All subsequent analyses were performed on the basis of this spreadsheet, using the open-source statistical package R (R Core Development Team, 2010).

4 Results

4.1 Overview of form frequencies

As Table 2 shows, a large number of differently inflected forms (types) were found for each of the 20 verbs studied. The frequencies of these forms, unsurprisingly, follow Zipf-like skewed distributions, with a very small number of high-frequency forms accounting for a high percentage of each verb’s tokens and a long ‘tail’ of very low-frequency forms accounting for a high percentage of their types.

These distributions suggest that both formulaicity and productive inflection are common. The ten most frequent forms identified all occurred on average more than once in every twenty minutes of reading time, strongly suggesting some type of formulaicity. At the other end of the spectrum, 39–68% of types of each lemma studied were hapax logomena, suggesting high levels of productivity (Baayen, 2008). The primary aim of this study, however, was to consider whether more complex formulaic patterns can be found below the level of the word. We shall now turn to this issue

4.2 Collocation between suffix combinations

The aim of this section is to determine the extent to which high-frequency combi-nations of morphemes occur across words. The initial approach will be to start with individual suffixes and determine the extent to which they enter into regular relationships with one another. On analogy with corpus work on relations tween orthographic words, I will refer to such relationships as collocations be-tween suffixes.

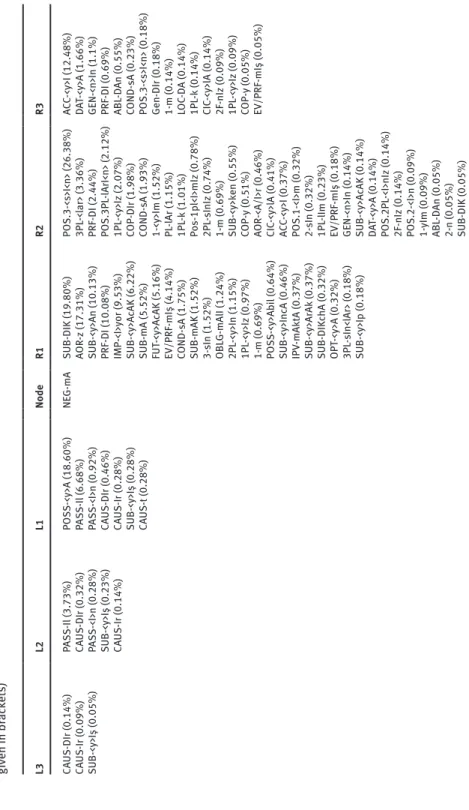

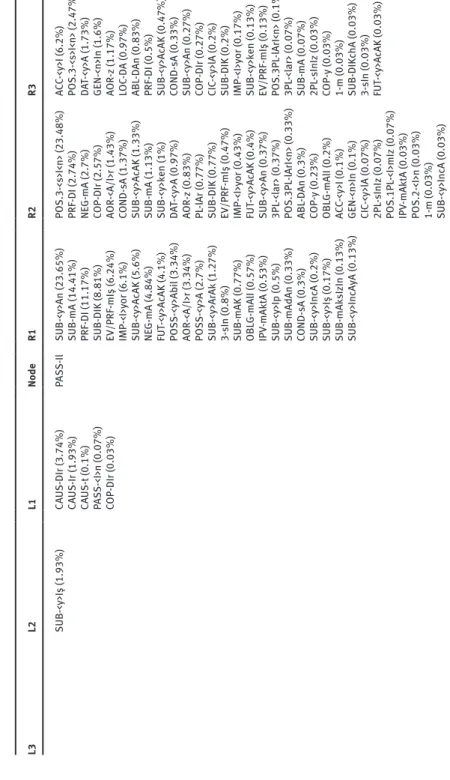

We can get an initial impression of the nature of collocation between suffixes by looking in detail at a few examples. Tables 4–7 show all of the morphological environments in which the four suffixes with the highest type frequencies (i.e. those used in the greatest number of different words) in the corpus appear and the percentage of tokens of the node suffix which are found with each collocate (I will take this percentage to indicate the strength of a collocational relationship). The columns in these tables indicate the position of the collocates – L1 collocates

12

Philip Durrant Ta ble 4: C ol loc ation s of the ‘NE G-mA ’ morp heme ( The per cent ag e of oc cu rrenc es of the node w ith whic h e ac h morp heme oc cu rs in thi s po sition i s gi ven in br ac ket s) L3 L2 L1 Node R1 R2 R3 CA US-DIr (0.14%) PAS S-Il (3.73%) PO SS-<y>A (18.60%) NE G-mA SUB-DIK (19.80%) PO S.3-<s>I<n> (26.38%) AC C-<y>I (12.48%) CA US-Ir (0.09%) CA US-DIr (0.32%) PAS S-Il (6.68%) AOR -z (17.31%) 3PL -<l ar> (3.36%) DA T-<y>A (1.66%) SUB-<y>Iş (0.05%) PAS S-<I>n (0.28%) PAS S-<I>n (0.92%) SUB-<y>An (10.13%) PRF-DI (2.44%) GEN-<n>In (1.1%) SUB-<y>Iş (0.23%) CA US-DIr (0.46%) PRF-DI (10.08%) PO S.3PL -lArI<n> (2.12%) PRF-DI (0.69%) CA US-Ir (0.14%) CA US-Ir (0.28%) IMP-<I>y or (9.53%) 1PL -<y>Iz (2.07%) ABL -D An (0.55%) SUB-<y>Iş (0.28%) SUB-<y>AcAK (6.22%) COP-DIr (1.98%) COND-sA (0.23%) CA US-t (0.28%) SUB-mA (5.52%) COND-sA (1.93%) PO S.3-<s>I<n> (0.18%) FUT -<y>AcAK (5.16%) 1-<y>Im (1.52%) Gen-DIr (0.18%) EV/PRF-mIş (4.14%) PL -lAr (1.15%) 1-m (0.14%) COND-sA (1.75%) 1PL -k (1.01%) LOC -D A (0.14%) SUB-mAK (1.52%) Po s-1p l<I>mIz (0.78%) 1PL -k (0.14%) 3-sIn (1.52%) 2PL -sInIz (0.74%) CIC -<y>lA (0.14%) OBL G-mA lI (1.24%) 1-m (0.69%) 2F-nIz (0.09%) 2PL -<y>In (1.15%) SUB-<y>k en (0.55%) 1PL -<y>Iz (0.09%) 1PL -<y>Iz (0.97%) COP-y (0.51%) COP-y (0.05%) 1-m (0.69%) AOR -<A/I>r (0.46%) EV/PRF-mIş (0.05%) PO SS-<y>A bi l (0.64%) CIC -<y>lA (0.41%) SUB-<y>IncA (0.46%) AC C-<y>I (0.37%) IPV -mA ktA (0.37%) PO S.1-<I>m (0.32%) SUB-<y>ArA k (0.37%) 2-sIn (0.32%) SUB-DIK chA (0.32%) 1PL -lIm (0.23%) OP T-<y>A (0.32%) EV/PRF-mIş (0.18%) 3PL -sIn<lAr> (0.18%) GEN-<n>In (0.14%) SUB-<y>Ip (0.18%) SUB-<y>AcAK (0.14%) DA T-<y>A (0.14%) PO S.2PL -<I>nIz (0.14%) 2F-nIz (0.14%) PO S.2-<I>n (0.09%) 1-yIm (0.09%) ABL -D An (0.05%) 2-n (0.05%) SUB-DIK (0.05%)

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

13 Ta ble 5: C ol loc ation s of the ‘SUB-mA ’ morp heme ( The per cent ag e of oc cu rrenc es of the node w ith whic h e ac h morp heme oc cu rs in thi s po sition i s gi ven in br ac ket s) L3 L2 L1 Node R1 R2 R3 SUB-<y>Iş (0.42%) PAS S-Il (1.1%) PAS S-Il (13.92%) SUB-mA PO S.3-<s>I<n> (49.37%) AC C-<y>I (9.12%) AP-k i<n> (0.26%) PAS S-Il (0.06%) CA US-DIr (0.81%) NE G-mA (3.87%) DA T-<y>A (10.92%) DA T-<y>A (6.83%) PRF-DI (0.16%) CA US-Ir (0.03%) SUB-<y>Iş (0.61%) PAS S-<I>n (2.45%) PO S. 3P L-l Ar I<n > ( 6. 64 % ) GEN-<n>In (6.06%) AC C-<y>I (0.06%) CA US-Ir (0.48%) CA US-DIr (1.58%) PL -lAr (6.25%) LOC -D A (2.67%) COND-sA (0.03%) PO SS-<y>A (0.26%) PO SS-<y>A bi l (1.19%) AC C-<y>I (4.35%) ABL -D An (2.51%) PAS S-<I>n (0.06%) SUB-<y>Iş (0.81%) GEN-<n>In (3.25%) CIC -<y>lA (1.71%) COP-DIr (0.03%) CA US-Ir (0.55%) PO S.1PL -<I>mIz (1.97%) COP-DIr (0.77%) CA US-t (0.03%) CA US-t (0.16%) PO S.1-<I>m (1%) PO S.1PL -<I>mIz (0.19%) LOC -D A (0.97%) COP-y (0.19%) PO S.2PL -<I>nIz (0.26%) PRF-DI (0.03%) CIC -<y>lA (0.19%) AP-k i<n> (0.03%)

COP-DIr (0.13%) POS.2-<I>n (0.1%)

14

Philip Durrant Ta ble 6: C ol loc ation s of the ‘P AS S-Il’ morp heme ( The per cent ag e of oc cu rrenc es of the node w ith whic h e ac h morp heme oc cu rs in thi s po sition i s gi ven in br ac ket s) L3 L2 L1 Node R1 R2 R3 SUB-<y>Iş (1.93%) CA US-DIr (3.74%) PAS S-Il SUB-<y>An (23.65%) PO S.3-<s>I<n> (23.48%) AC C-<y>I (6.2%) CA US-Ir (1.93%) SUB-mA (14.41%) PRF-DI (2.74%) PO S.3-<s>I<n> (2.47%) CA US-t (0.1%) PRF-DI (11.17%) NE G-mA (2.7%) DA T-<y>A (1.73%) PAS S-<I>n (0.07%) SUB-DIK (8.81%) COP-DIr (2.57%) GEN-<n>In (1.6%) COP-DIr (0.03%) EV/PRF-mIş (6.24%) AOR -<A/I>r (1.43%) AOR -z (1.17%) IMP-<I>y or (6.1%) COND-sA (1.37%) LOC -D A (0.97%) SUB-<y>AcAK (5.6%) SUB-<y>AcAK (1.33%) ABL -D An (0.83%) NE G-mA (4.84%) SUB-mA (1.13%) PRF-DI (0.5%) FUT -<y>AcAK (4.1%) SUB-<y>k en (1%) SUB-<y>AcAK (0.47%) PO SS-<y>A bi l (3.34%) DA T-<y>A (0.97%) COND-sA (0.33%) AOR -<A/I>r (3.34%) AOR -z (0.83%) SUB-<y>An (0.27%) PO SS-<y>A (2.7%) PL -lAr (0.77%) COP-DIr (0.27%) SUB-<y>ArA k (1.27%) SUB-DIK (0.77%) CIC -<y>lA (0.2%) 3-sIn (0.8%) EV/PRF-mIş (0.47%) SUB-DIK (0.2%) SUB-mAK (0.77%) IMP-<I>y or (0.43%) IMP-<I>y or (0.17%) OBL G-mA lI (0.57%) FUT -<y>AcAK (0.4%) SUB-<y>k en (0.13%) IPV -mA ktA (0.53%) SUB-<y>An (0.37%) EV/PRF-mIş (0.13%) SUB-<y>Ip (0.5%) 3PL -<l ar> (0.37%) PO S.3PL -lArI<n> (0.1%) SUB-mAdAn (0.33%) PO S.3PL -lArI<n> (0.33%) 3PL -<l ar> (0.07%) COND-sA (0.3%) ABL -D An (0.3%) SUB-mA (0.07%) SUB-<y>IncA (0.2%) COP-y (0.23%) 2PL -sInIz (0.03%) SUB-<y>Iş (0.17%) OBL G-mA lI (0.2%) COP-y (0.03%) SUB-mA ksIzIn (0.13%) AC C-<y>I (0.1%) 1-m (0.03%) SUB-<y>IncA yA (0.13%) GEN-<n>In (0.1%) SUB-DIK chA (0.03%) CIC -<y>lA (0.07%) 3-sIn (0.03%) 2PL -sInIz (0.07%) FUT -<y>AcAK (0.03%) PO S.1PL -<I>mIz (0.07%) IPV -mA ktA (0.03%) PO S.2-<I>n (0.03%) 1-m (0.03%) SUB-<y>IncA (0.03%)

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

15 Ta ble 7: C ol loc ation s of the ‘PO S.3-<s>I<n>’ morp heme ( The per cent ag e of oc cu rrenc es of the node w ith whic h e ac h morp heme oc cu rs in thi s po sition is gi ven in br ac ket s) L3 L2 L1 Node R1 R2 R3 PAS S-Il (1.39%) PAS S-Il (13.21%) SUB-DIK (61.23%) PO S.3-<s>I<n> AC C-<y>I (30.46%) AP-k i<n> (0.11%) PO SS-<y>A (1.2%) NE G-mA (10.73%) SUB-mA (28.74%) DA T-<y>A (6.08%) PRF-DI (0.11%) CA US-DIr (0.71%) PO SS-<y>A bi l (2.44%) SUB-<y>AcAK (9.77%) GEN-<n>In (3.51%) COND-sA (0.02%) SUB-<y>Iş (0.53%) PAS S-<I>n (2.25%) SUB-<y>An (0.15%) LOC -D A (2.53%) CA US-Ir (0.43%) CA US-DIr (1.09%) SUB-<y>Iş (0.09%) ABL -D An (1.95%) PAS S-<I>n (0.21%) SUB-<y>Iş (0.58%) AOR -z (0.02%) CIC -<y>lA (0.88%) NE G-mA (0.08%) CA US-Ir (0.28%) COP-DIr (0.41%) COP-DIr (0.02%) CA US-t (0.04%) COP-y (0.13%) CA US-t (0.02%) AOR -<A/I>r (0.02%)

16

Philip Durrant

are those one position to the left of the node, R2 collocates are those two positions to the right, and so on.

These data suggest a number of working hypotheses. First, it seems that the strongest collocates are usually found immediately adjacent to the node mor-pheme (i.e. at L1 and R1). The only exception is seen in Table 4, where the stron-gest right-hand collocate of NEG-mA is POS.3-<s>I<n>, found at R2. This is likely to be a product of the large number of subordinating morphemes (i.e. those pre-fixed SUB-) found at R1 (a similar effect also seen in Table 6, where again the POS.3-<s>I<n> suffix is common at R2). The possessive POS.3-<s>I<n> is (as Table 7 demonstrates) commonly used directly after such morphemes – a relationship analogous to possessive + gerund forms in English. Thus, while most important collocational relations seem to hold between directly adjacent morphemes, there also seem to be some discontinuous collocations, recalling the lexical bundles with variable slots identified in English by Biber (2009).

Second, all four morphemes appear in pairings which occur once only, even at the immediately adjacent L1/R1 slots, where collocational relations tend to be strongest: CAUS-t + NEG-mA (Table 4); SUB-mA + COP-y (Table 5); COP-DIr + PASS-Il (Table 6); and AOR-z + POS.3-<s>I<n> (Table 7) are all hapax logomena. All four node morphemes therefore take part in novel (or at least very low-frequency) combinations. At the same time, all four morphemes also enter into strong collo-cations. Almost a third of cases of NEG-mA are directly preceded by the mor-pheme POSS-<y>A (Table 4), while well over a third of cases of SUB-mA are directly followed by POS.3-<s>I<n> (Table 5). Most strikingly of all, over 99% of occurrences of POS.3-<s>I<n> are directly preceded by one of just three other mor-phemes (Table 7). PASS-Il forms weaker relationships, but nevertheless in around one in four occurrences it is directly followed by SUB-<y>An (Table 6).

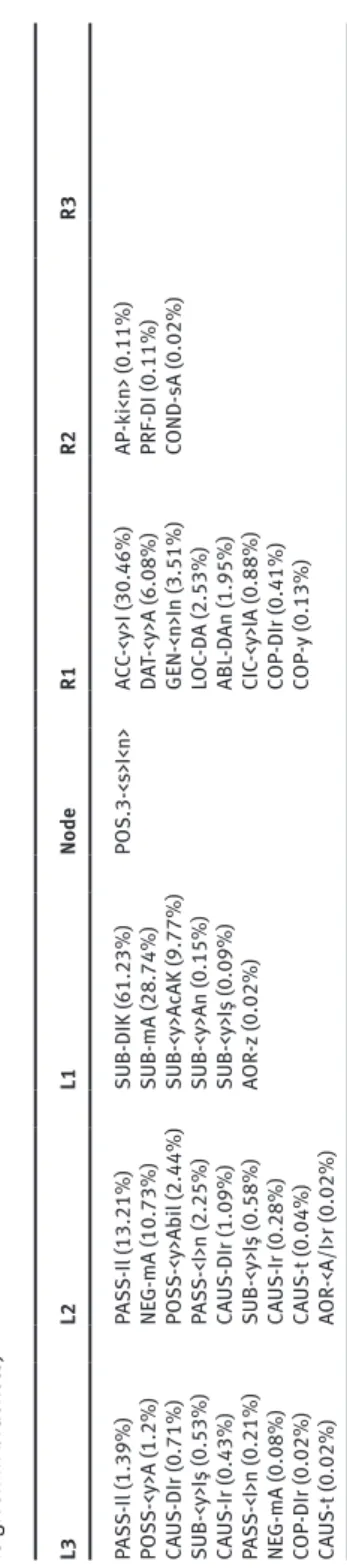

The description so far makes clear that there is considerable variation be-tween suffixes in the types and strengths of collocational relationship into which they enter. Before drawing any strong conclusions, therefore, it will be important to extend the analysis beyond this small set. To get a broader picture, I calculated for all high-frequency morphemes (i.e., the 29 morphemes which appear in 100 distinct words or more), the total number of morphemes appearing in each posi-tion from L3 to R3. To estimate the predictability of their collocaposi-tional environ-ments, I also calculated the percentage of cases of the node morpheme occurring with one of the top 3 collocates in that position (or fewer if the node did not have as many as 3 collocates in that position. For example, only one suffix is ever found directly after POSS-<y>A, so the 100% figure reported for that morpheme is based on this one collocate only). This percentage will be referred to as a morpheme’s collocate predictability. Table 8 shows the results for each morpheme; Table 9 summarises the collocate predictability at each position.

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

17 Ta ble 8: Nu m ber and st reng th of co lloc ating morp heme s f or high-f requency suffi xe s (In e ac h c ol loc at e c el l, the fir st nu m ber indic at es the t ot al nu m ber of diff er ent morp heme ty pe s f ou nd in thi s po

sition; the sec

ond nu m ber indic at es the per cent ag e of oc cu rrenc es of the node w ith whic h the thr ee (or f ew er) mo st fr equent morp heme ty pe s appe ar) Ro w no . L3 L2 L1

Node (type/t

ok en f requency) R1 R2 R3 8.1 3 / 0.28% 5 / 4.33% 7 / 26.2% NE G-mA (711/2,172) 24 / 47.24% 32 / 32.18% 16 / 15.24% 8.2 9 / 3.3% 9 / 26.37% 6 / 99.74% PO S.3-<s>I<n> (608/5,331) 8 / 40.05% 3 / 0.24% 0 / 0% 8.3 0 / 0% 1 / 1.93% 5 / 5.77% PAS S-Il (544/2,998) 24 / 49.23% 31 / 28.92% 26 / 10.41% 8.4 3 / 0.52% 8 / 2.51% 8 / 20.24% SUB-mA (528/3,103) 14 / 66.94% 11 / 22.01% 4 / 0.48% 8.5 9 / 1% 20 / 4.69% 19 / 20.03% PRF-DI (424/4,118) 8 / 12.94% 1 / 0.41% 3 / 0.15% 8.6 4 / 0.27% 8 / 1.83% 10 / 18.49% SUB-DIK (398/4,040) 9 / 94.65% 11 / 39.48% 4 / 0.15% 8.7 10 / 23.43% 12 / 90.3% 9 / 92.74% AC C-<y>I (296/2,134) 0 / 0% 0 / 0% 0 / 0% 8.8 4 / 1.88% 7 / 10.6% 8 / 45.89% SUB-<y>AcAK (284/1,009) 7 / 64.12% 6 / 35.98% 1 / 0.1% 8.9 2 / 0.52% 5 / 5.34% 9 / 25.73% IMP-<I>y or (260/1,772) 9 / 24.45% 9 / 1.05% 0 / 0% 8.10 0 / 0% 4 / 0.95% 7 / 21.99% PO SS-<y>A bi l (248/632) 15 / 78.01% 18 / 28.32% 8 / 9.97% 8.11 2 / 0.15% 6 / 4.89% 7 / 31.43% AOR -<A/I>r (240/1,330) 11 / 38.57% 9 / 4.51% 1 / 0.08% 8.12 3 / 0.59% 7 / 1.92% 10 / 28.37% SUB-<y>An (220/3,899) 10 / 11.62% 11 / 5.36% 5 / 0.21% 8.13 6 / 1.02% 11 / 2.77% 13 / 27.17% EV/PRF-mIş (216/1,082) 8 / 45.01% 5 / 4.53% 0 / 0% 8.14 1 / 0.25% 3 / 1.47% 5 / 22.11% PO SS-<y>A (202/407) 2 / 100% 19 / 63.88% 20 / 26.78% 8.15 4 / 0.71% 5 / 3.46% 8 / 26.63% FUT -<y>AcAK (195/984) 9 / 30.79% 8 / 1.63% 0 / 0% 8.16 0 / 0% 0 / 0% 2 / 51.86% CA US-DIr (191/403) 22 / 53.1% 37 / 28.04% 17 / 14.14% 8.17 3 / 2.58% 5 / 9.78% 5 / 91.44% PO S.3PL -lArI<n> (177/736) 8 / 43.48% 2 / 0.41% 0 / 0% 8.18 8 / 3.06% 12 / 17.01% 16 / 43.71% COND-sA (176/588) 6 / 21.26% 1 / 10.2% 2 / 1.7% 8.19 9 / 13.01% 13 / 50.88% 8 / 90.28% DA T-<y>A (172/792) 0 / 0% 0 / 0% 0 / 0% 8.20 6 / 8.41% 9 / 22.63% 11 / 71.55% 3PL -<l ar> (162/464) 5 / 13.15% 1 / 0.22% 0 / 0% 8.21 7 / 3.48% 14 / 29.51% 17 / 72.34% COP-DIr (154/488) 3 / 0.82% 1 / 0.2% 1 / 0.2% 8.22 0 / 0% 0 / 0% 0 / 0% PAS S-<I>n (136/559) 22 / 55.64% 23 / 32.56% 15 / 10.38% 8.23 2 / 0.51% 6 / 16.64% 5 / 99.49% PL -lAr (132/583) 12 / 45.8% 7 / 2.06% 0 / 0% 8.24 8 / 15.52% 9 / 71.26% 8 / 81.61% GEN-<n>In (128/522) 1 / 0.38% 0 / 0% 0 / 0% 8.25 4 / 4.07% 7 / 21.29% 8 / 87.56% 1PL -<y>Iz (112/418) 1 / 0.24% 0 / 0% 0 / 0% 8.26 1 / 0.08% 5 / 1.83% 7 / 8.04% SUB-mAK (106/1256) 4 / 16.16% 1 / 0.24% 0 / 0% 8.27 7 / 13.06% 10 / 45.54% 10 / 83.12% ABL -D An (106/314) 2 / 1.27% 0 / 0% 0 / 0% 8.28 0 / 0% 0 / 0% 1 / 1.35% SUB-<y>Iş (105/370) 19 / 79.73% 26 / 31.08% 34 / 15.41% 8.29 3 / 2.32% 9 / 12.25% 4 / 92.72% PO S.1PL -<I>miz (101/302) 6 / 21.19% 0 / 0% 0 / 0%

18

Philip Durrant

As Tables 8 and 9 show, collocate predictability does, in general, drop rapidly as collocates move further from the node. Only four morphemes have a figure of greater than 45% at L2, i.e.: ACC-<y>I (Row 7); DAT-<y>A (Row 19); GEN-<n>In (Row 24); ABL-DAn (Row 27).

The occurrence of these discontinuous collocates appears to be closely relat-ed to forms’ grammatical function. These four morphemes (Accusative, Dative, Genitive, and Ablative suffixes) correspond to four of the five suffixes classified by Göksel and Kerslake as ‘Case Suffixes’ (Göksel & Kerslake, 2005, p. 70), used here to modify nominalized verbs. The fifth case suffix, LOC-DA (not listed in Table 8 because it did not meet the frequency requirements) also shows high restriction at L2, with 85.65% of cases featuring one of three morphemes.

Only one suffix has similarly high levels of association at R2. This is the suffix POSS-<y>A, which indicates impossibility and is always followed by the negative suffix NEG-mA. The former is exceptional in being the only morpheme examined to be always accompanied by one particular collocate (suggesting, as we shall see below, that these two items may constitute a single complex unit). Given the strength of its R1 collocation, it is unsurprising that it also has strong collocates at R2.

In the node-adjacent slots (L1 and R1), collocate predictability is generally high – the top 3 (or fewer) collocates accounting for, on average, around 38–40% of occurrences of the node. As the interquartile ranges indicate, however, there is wide variation around this median. Though the majority of suffixes form strong collocations either to left or right – 19/29 suffixes have a score of at least 50% on one side or the other – a few suffixes do not seem to enter into strong colloca-tional relations. In particular, the infinitive form SUB-mAK (Row 26) and the per-fective PRF-DI (Row 5) are both used together with a wide range of other suffixes and do not have any collocate predictability scores exceeding 20%.

At the other end of the scale, the high level of collocate predictability of many morphemes at L1 or R1 suggests that there is likely to be some psycholinguistic link between them and their collocates, or that the combinations may be inde-pendently stored items. For 9/29 node suffixes, for example, over 90% of occur-Table 9: Summary of collocation strengths

L3 L2 L1 R1 R2 R3

Median 1.45 7.56 37.57 40.05 5.36 1.7

Min 0.08 0.95 1.35 0.24 0.2 0.08

Max 23.43 90.3 99.74 100 63.88 26.78

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

19

rences are found together with one of the top 3 (or fewer) collocates. This hypoth-esis is reinforced by the very high frequency of some of these pairings. Table 10 shows the 10 most frequent pairings found. Absolute frequency data are not given since the present data can tell us only how often the combinations occurred in inflections of the 20 verbs studied, not how frequent they were in the corpus as a whole. Frequency is therefore given in terms of the percentage of verb tokens which include each pair. To indicate how widely each bundle is used, figures are also given for the number of different verb types (out of the 3,198 forms studied) and the number of different verb roots (out of the 20 studied) with which they were found.

Assuming that the verb roots studied are representative of verbs in general, these pairings are extremely common. The most frequent pairing (the third- person subordinating form SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n>) was found in 12.59% of verb forms, suggesting that it must occur at least once in every few lines of text. In-deed, even the least frequent pairing in this top 10 is found on average around once every 70 verbs. These extremely high frequencies, together with the wide spread of the collocations across different verb roots and the regular syntactic function which each performs, suggest that some form of psycholinguistic en-trenchment is extremely likely.

From the analysis so far, we can draw two main conclusions. First, most high-frequency suffixes enter into both novel and regular combinations. Thus, while the language system must allow for the use of each individual morpheme in novel constructions, the dominance of certain high-frequency pairings suggests that an efficient usage-based system should also represent the typical immediate mor-phological environments of many suffixes. Second, strong collocations usually consist of two adjacent morphemes only. The exceptions are combinations which Table 10: 10 most common adjacent two-word collocations

Bundle Types Roots % verb form tokens

SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> 197 20 12.59 POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I 152 19 6.26 SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> 249 20 5.91 PASS-Il SUB-<y>An 37 15 2.73 SUB-<y>AcAK POS.3-<s>I<n> 152 19 2.01 PASS-Il SUB-mA 99 16 1.81 NEG-mA SUB-DIK 86 18 1.68 POSS-<y>A NEG-mA 200 17 1.56 SUB-DIK POS.3PL-lArI<n> 69 18 1.48 NEG-mA AOR-z 97 17 1.45

20

Philip Durrant

include a case suffix and those which include the negative possibility marker POSS-<y>A. The longer combinations which include these elements will be examined in more detail in the next section.

4.3 Morphemic bundles

To examine in more detail the prevalence and nature of longer collocations, I generated lists of the most common three- and four-morpheme bundles. The term bundle is adopted from the work of Biber and his colleagues (1999) on recurrent word combinations, and is used here to refer to frequently recurring sequences of morphemes.

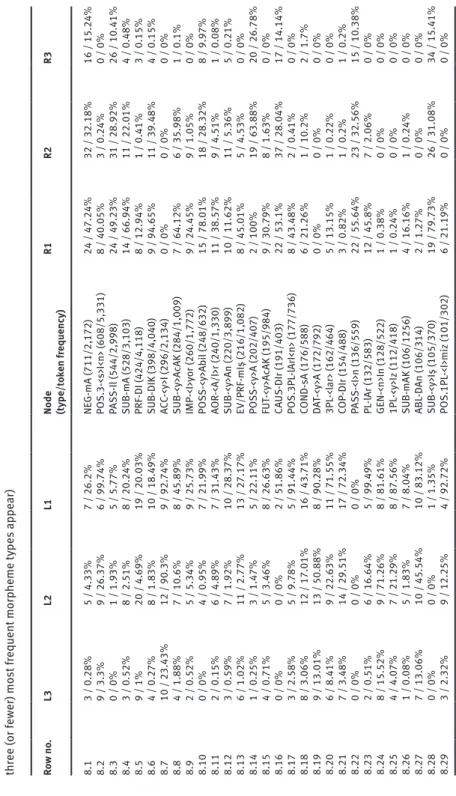

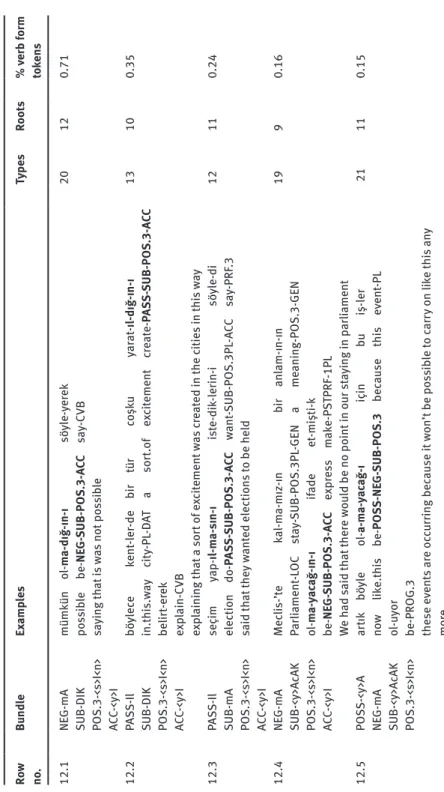

The ten most common combinations of each length are shown in Tables 11 and 12. Examples from the corpus of each suffix cluster in use are also given, along with an English gloss. It should be noted these clusters can be integrated with other morphemes to make still longer words, but that for simplicity of pre-sentation, such examples are not included in these tables. As in Table 10, fre-quency is given in terms of the percentage of verb tokens which include each bundle and the number of different verb roots with which they were found. For ease of presentation, bundles will be referred to using the row numbers given in the tables.

These data reveal a number of important facts. First, the three-morpheme combinations in Table 11 are all very common indeed. Since they also have regular grammatical functions, this makes some kind of holistic storage seem likely, given a usage-based view of language. Assuming that the verbs studied here are representative of those in the rest of the corpus, the most common combination (11.1) is used in almost one in twenty verb tokens. A speaker who had memorised all of the top ten three-morpheme forms would on average meet one of them in 12.38% of the verbs found in the present corpus. The four-morpheme combina-tions are considerably less frequent, between them accounting for only 2.22% of verbs.

Second, most of the three-morpheme combinations are used across a wide range of verb roots, all but two (11.8, 11.10) being attested with at least three quar-ters of the verbs studied. This reinforces the impression that an efficient language system may draw on some kind of representation of these bundles for use across a range of lexical contexts. For four-morpheme suffixes, the spread is much nar-rower, the majority of combinations being used with fewer than half of the twenty verbs studied.

Third, frequent combinations of three or more items are dominated by two structural types. 18/20 of the combinations identified include combinations of

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

21 Ta ble 11: 10 mo st common thr ee-morp heme b und le s Ro w no . Bu nd le Ex amp le s Ty pe s Root s % verb f orm to ken s 11.1

SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I

“Ç oc uk -lar -a ok ul yeti ştir -e-mi-yor -uz” de-diğ -in-i öne s ür -dü “c hi ld-PL -D AT sc hoo l k eep .u p-PO SS-NE G-PROG-1PL ” s ay -SUB-PO S.3-A CC c laim-PRF .3 cl aimed th at he s aid th at “W e c an’t b ui ld eno ugh sc hoo ls for the c hi ldr en” 59 17 4.57 11.2 PAS S-Il SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> Çü nk ü bı ra k-ıl-m a-sı is te-n-i yor Bec au se r ele ase-PAS S-SUB-PO S.3 r eque st -P AS S-PROG.3 Bec au se it is reque st ed th at he be r ele ased 67 16 1.50 11.3 NE G-mA SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> olu m lu bir s in ya l ver -me-diğ -i mu ha kk ak po siti ve a me ss ag e gi ve-NE G-SUB-PO S.3 i s.c er tain 51 16 1.48 it c er tain ly didn’t gi ve a po siti ve me ss ag e 11.4 PAS S-Il SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> darbe h azı rlı k-l arı n-ı n konu ş-ul-duğ -u top lant ı-d a co up pr ep ar ation-PO S.3PL -GEN di sc us s-PAS S-SUB-PO S.3 meeting -L OC 46 16 0.97 at

the meeting in whic

h the c ou p pr ep ar ation s w er e di sc us sed 11.5

SUB-<y>AcAK POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I

görü şme s ür ec -in-de bir t ık anı klı k o l-ac ağ -ın-ı san-mı-yor -u m meeting pr oc es s-PO S.3-L OC a ho ld .u p be-SUB-PO S.3-A CC thin k-NE G-PROG-1 53 16 0.86 I don’t thin k ther e w ill be a ho ld u p in the meeting pr oc es s 11.6

SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I

Hem de p arlement o ç alı ş-m a-sı n-ı bi l-i yor -u m Al so parli ament work -SUB-PO S.3-A CC kno w-PROG-1 38 18 0.82 And I kno w the w ork ing s of p arli ament 11.7

SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> DAT-<y>A

ol ay -lar -ın çı k-m a-sı n-a eng el ol-m a-ya ça lış-t ı inc ident -PL -GEN oc cu r-SUB-PO S.3-D AT o bs truction be-SUB-D AT t ry -PRF .3 tried to s top inc ident s oc cu rring 27 16 0.61 11.8 PO SS-<y>A NE G-mA AOR -z Öğr enc i sı nıf -a şap ka i le gir -e-me-z St udent c la ss-D AT h at -CVB ent er -PO SS-NE G-A OR.3 39 13 0.58 A s tudent cannot g o t o c la ss w ear ing a h at 11.9 SUB-DIK POS.3PL -lArI<n> AC C-<y>I bir mekt up y ol la-yar ak y aş a-dı k-l arı n-ı biz -ler -le pa yl aş-m ak i st e-mi ş-ler a lett er send-CVB ex per ienc e-SUB-PO S.3PL -A CC u s-PL -OBL s har e-INF want -PRF-3PL 22 15 0.51 by sending a lett er they w ant ed to s har e wh at they h ad e xper ienc ed w ith u s 11.10

SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> DAT-<y>A

Ba şk an-ı n an lat -tığ -ın-a gör e Ch air .per so-GEN e xp lain-SUB-PO S.3-D AT ac cor ding.t o 18 12 0.48 Ac cor ding t o the c hair per son

22

Philip Durrant Ta ble 12: 10 mo st common f ou r-morp heme b und le s Ro w no . Bu nd le Ex amp le s Ty pe s Root s % verb f orm to ken s 12.1 NE G-mA SUB-DIK POS. 3-<s >I< n> AC C-<y>I mü m kü n o l-m a-dığ -ın-ı sö yle-yer ek po ss ib le be-NE G-SUB-PO S.3-A CC s ay -CVB sa ying th at is w as not po ss ib le 20 12 0.71 12.2 PAS S-Il SUB-DIK POS. 3-<s >I< n> AC C-<y>I bö ylec e kent -ler -de b ir t ür co şk u yar at -ıl-dığ -ın-ı in.thi s.w ay c ity -PL -D AT a sor t.of e xc itement c re at e-PAS S-SUB-PO S.3-A CC belir t-er ek ex pl ain-CVB ex pl aining th at a sor t of e xc itement w as cr eat ed in the c itie s in thi s w ay 13 10 0.35 12.3 PAS S-Il SUB-mA POS. 3-<s >I< n> AC C-<y>I seç im yap-ıl-m a-sı n-ı is te-di k-ler in-i sö yle-di election do-PAS S-SUB-PO S.3-A CC w ant -SUB-PO S.3PL -A CC s ay -PRF .3 said th at they w ant ed election s t o be held 12 11 0.24 12.4 NE G-mA SUB-<y>AcAK POS. 3-<s >I< n> AC C-<y>I Mec lis-’t e ka l-m a-mız -ın bir an lam-ı n-ı n Parli ament -L OC s ta y-SUB-PO S.3PL -GEN a me aning -PO S.3-GEN ol-m a-yac ağ -ın-ı ifade et -mi şti-k be-NE G-SUB-PO S.3-A CC e xpr es s m ak e-P ST PRF-1PL W e h ad said th at ther e w ou ld be no po int in o ur s ta ying in p arli ament 19 9 0.16 12.5 PO SS-<y>A NE G-mA SUB-<y>AcAK POS. 3-<s >I< n> ar tık bö yle ol-a-m a-yac ağ -ı iç in bu iş-ler no w lik e.thi s be-PO SS-NE G-SUB-PO S.3 bec au se thi s ev ent -PL ol-u yor be-PROG.3 these ev ent s ar e oc cu rring bec au se it w on’t be po ss ib le t o c arr y on li ke thi s an y mor e 21 11 0.15

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

23 12.6 PAS S-Il SUB-mA POS. 3-<s >I< n> GEN-<n>In fark lılı k-l ar -ın ifade ed- il-me-sin-in dü şm an-ı dıff er enc e-PL -GEN e xpr es sion m ak e-PAS S-SUB-PO S.3-GEN enem y-PO S.3 an enem y t o diff er enc es being e xpr es sed 9 9 0.13 12.7 PAS S-Il SUB-mA POS. 3-<s >I< n> DA T-<y>A çı pl ak ol-ar ak deniz -e gir -il-me-sin-e iz in na ked be-CVB se a-D AT ent er -P AS S-SUB-PO S.3-D AT permi ss ion ver -il-me-yec ek gi ve-P AS S-NE G-FUT .3 permi ss ion t o g o int o the se a n ak ed w ill not be gi ven 6 5 0.13 12.8 PAS S-Il PO SS-<y>A NE G-mA AOR -z Bu iddi a-l ar cev ap-sız bı ra k- ıl-a-m a-z Thi s c laim-PL an sw er -NE G le av e-PAS S-PO SS-NE G-A OR.3 The se c laim s c annot be left u nan sw er ed 5 4 0.13 12.9 PO SS-<y>A bi l SUB-<y>AcAK POS. 3-<s >I< n> AC C-<y>I kat ar akt -tan koru-ya bi l-ec eğ -in-i gö st er -diğ -in-i cat ar act -ABL pr ot ect -PO SS-SUB-PO S.3-A CC s ho w-SUB-PO S.3-A CC belir t-ti ex pl ain-PRF .3 ex pl ained th at thi s s ho wed th at it co uld pr ot ect ag ain st cat ar act s 12 8 0.13 12.10 PAS S-Il NE G-mA SUB-mA POS. 3-<s >I< n> Bö yle si önem li bir t es is-e zar ar v er -il-me-me-si Suc h impor tant a fac ility -D AT h arm gi ve-PAS S-NE G-SUB-PO S.3 ger ek -iy or nec es sit at e-PROG.3 suc h an impor tant fac ility sho uldn’t be h armed 10 6 0.09

24

Philip Durrant

subordinators plus person markers, while the remaining two (11.8, 12.8) involve negative forms. Interestingly, Biber and his colleagues have noted that lexical bundles in English often involve parts of embedded complement clauses, such as I don’t know why or I thought that (Biber, et al., 1999, p. 991). The high-frequency morpheme bundles seen here seem therefore to play a similar structural role to many word bundles found in English – i.e. that of anchoring complex sentences. This fits well with the view that one aim of formulaic language is to enable speakers to fluently negotiate utterances which involve more than a single clause (Pawley & Syder, 2000).

Finally, it is important to note that (as their structural similarities would already suggest) there are strong family resemblances across the most frequent morpheme bundles. Table 13 organizes the combinations to highlight these simi-larities. Looking across the examples here, the impression is not of twenty sepa-rate forms, but rather of a smaller number of form sets, or of prototypes permit-ting predictable variations. The situation is comparable to that noted in English by, for example, Durrant (2009), who points out that variable forms such as there was/were (no/a) statistically significant difference(s) between/in appear to be more common than entirely fixed formulas. Given the prominence of such Table 13: Relations between bundles

SUB-DIK POS.3PL-lArI<n> ACC-<y>I SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I NEG-mA SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n>

NEG-mA SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I PASS-Il SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n>

PASS-Il SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> DAT-<y>A SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I PASS-Il SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n>

PASS-Il SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> DAT-<y>A PASS-Il SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> DAT-<y>A PASS-Il SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> GEN-<n>In PASS-Il NEG-mA SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n>

SUB-<y>AcAK POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I NEG-mA SUB-<y>AcAK POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I POSS-<y>Abil SUB-<y>AcAK POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I POSS-<y>A NEG-mA SUB-<y>AcAK POS.3-<s>I<n>

PASS-Il POSS-<y>A NEG-mA AOR-z POSS-<y>A NEG-mA AOR-z

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

25 cases, the idea of independent, fixed complex forms may be a misleading one. It may be better to see formulas rather as variable prototypes, or families of related forms.

4.4 Spread of suffix combinations across verb roots

The fact that the three-morpheme bundles shown in Table 11 are attested across a wide range of lemmas implies that they are relatively productive – i.e. available for use in many lexical contexts. This might suggest that the language system represents such bundles as purely grammatical items, independent of the lexical roots to which they are applied. Such a conclusion would be surprising from a usage-based perspective however. As was noted in the introduction, usage-based models reject any sharp distinction between grammar and lexis, and one of the key findings of recent corpus linguistics has been that particular grammatical forms are commonly associated with particular lexis, and vice-versa (Hoey, 2005; Hunston & Francis, 2000; Stefanowitsch & Gries, 2003).

This phenomenon has been most systematically studied by Stefanowitsch & Gries (2003), who developed the technique of ‘collostruction analysis’ to quantify such associations. They use Fisher’s exact test to determine the probability that there is a relationship of either attraction or repulsion between a particular lexical item and a particular grammatical form. Significant results are taken to indicate either an attraction or repulsion, and the lexis associated with a particular pat-tern ranked according to their p-values.

Using this method, Stefanowitsch and Gries (2003) demonstrate that syntac-tic structures at a variety of levels of abstraction are biased towards parsyntac-ticular lexical instantiations. Unsurprisingly, the slots in relatively specific constructions like (X think nothing of Vgerund] are relatively limited in the lexis which they accept

(the V slot being associated with verbs indicating undesirable/risky activities). Perhaps less expectedly though, even relatively abstract grammatical forms, such as the past tense, are significantly attracted to some verbs (such as be and say) and repelled by others (such as know and do). Stefanowitsch and Gries do not attempt to explain associations of the latter sort, but point out that their very existence represents a significant problem for models of language in which syn-tax is strictly separated from lexis.

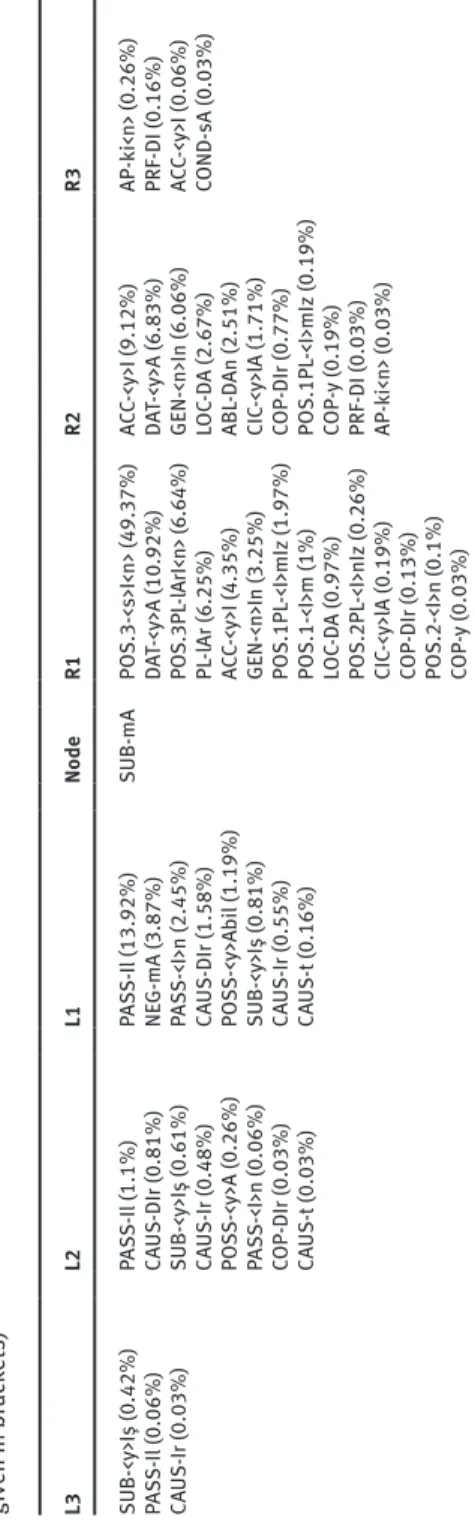

The final analysis in this paper will adopt Stefanowitsch and Gries’s (2003) technique to determine whether the 3-morpheme bundles identified in the pre-vious section are equally likely to appear with all of the verbs they are attested or whether there are significant relationships of attraction/repulsion between

26

Philip Durrant

particular bundles and particular verb roots. Like Stefanowitsch and Gries, I will take a prevalence of such associations to suggest that a model on which suffix bundles are represented entirely independently of lexical roots is problematic.

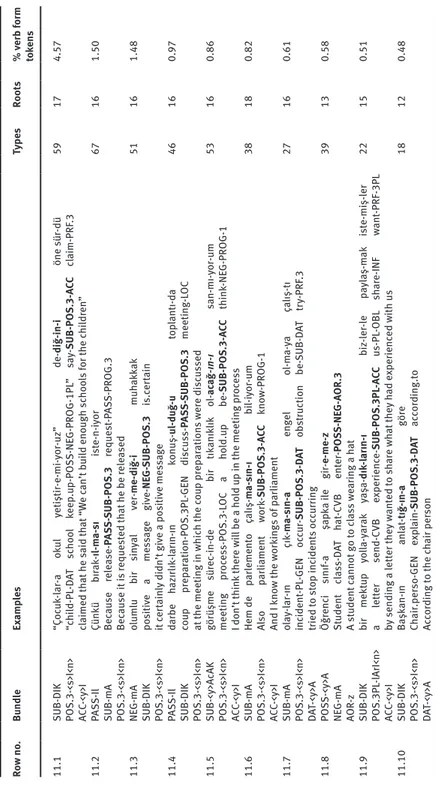

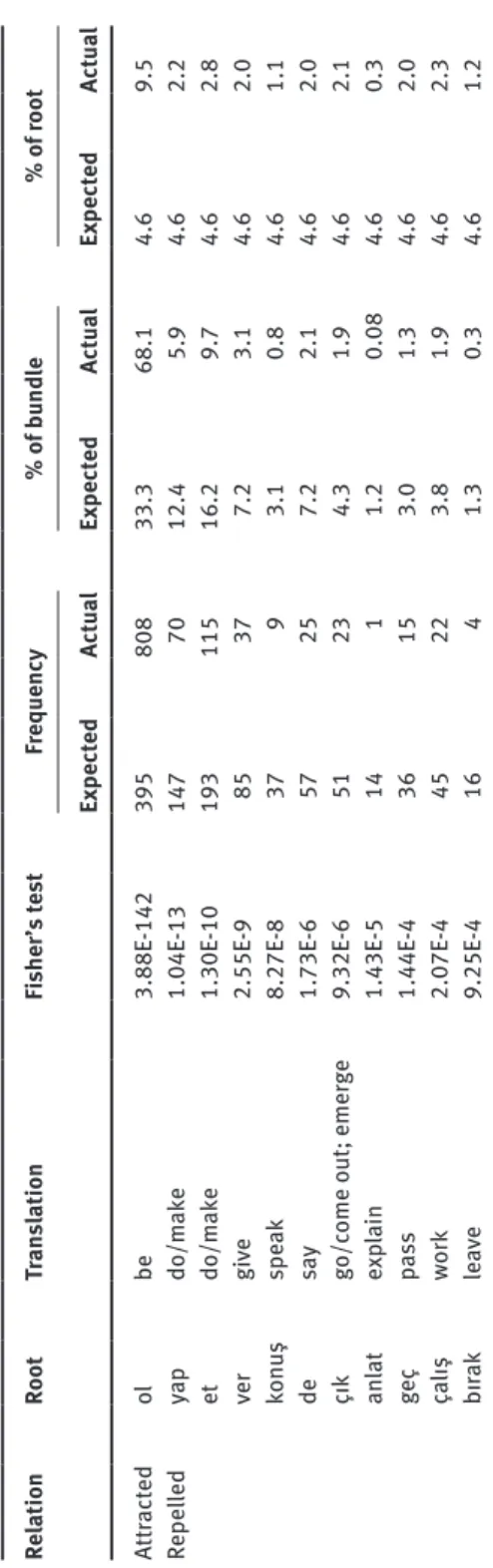

As a first step, we can consider the lexical associations of the most frequent bundle in the corpus – the SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I bundle, which was attested with 17 of the 20 verb roots studied. Table 14 shows all roots which are shown by Fisher’s exact test to be either attracted to or repelled by the bundle with a significance of p < .001. As is immediately obvious from the table, occur-rences of this bundle are overwhelmingly dominated by forms using a single root: ol (‘be’). If uses of the bundle were distributed between the attested roots in pro-portion to their appearance in the corpus as a whole (the null hypothesis we would expect were grammar and lexis independent of each other), we would expect to find 395 co-occurrences of this root and suffix bundle. However, the actual count is over twice this figure, at 808. Indeed, over 68% of cases of this bundle are instantiated with this particular root (compared to the 33% we would expect given the overall frequency of ol). Moreover, the attraction is mutual: the ol root shows a strong preference for this particular bundle, with almost 10% of its occurrences being found with this bundle (compared to the 4.6% we would expect given the overall frequency of the bundle).

Unsurprisingly, given this strong skew towards ol, many other roots are found to occur far less frequently with the bundle than the null hypothesis would pre-dict. The strongest repulsion is found for the root yap (‘do’/‘make’), which is found in this form on 70 times, compared to the 147 we would expect on the null hypothesis.

This analysis suggests that, while this bundle is available for use across most verb roots, grammar and lexis are not independent of each other. It remains to be seen, however, to what extent such associations exist for other morphemic bun-dles. Table 15 shows the roots with are attracted to/repelled by each of the ten most frequent three-morpheme bundles with a significance of p < .001. The most obvious, and most important, point to note here is that only one bundle (SUB-DIK POS.3PL-lArI<n> ACC-<y>I) does not show any such associations. The phenome-non of collostruction therefore appears to be widespread in Turkish. This suggests that lexis and syntax are unlikely to be entirely distinct in the language system of the reader whose experience is represented by the current corpus.

Second, certain commonalities are evidenced across bundles. Specifically: – All bundles which include the two-morpheme combination SUB-DIK

POS.3-<s>I<n> and do not include the passive morpheme PASS-Il (rows 15.1, 15.3, and 15.10) are attracted to the root ol (‘be’) and repelled by the roots yap (‘do’/‘make’) and et (‘do’/‘make’). The ol root it not attracted to, and the et/ yap roots not repelled by, any other bundles.

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

27 Ta ble 14: Le xic al a ssoc iation s of the SUB-DIK P OS .3-<s>I<n> A CC -<y >I b und le Rel ation Root Tr an sl ation Fis her’s te st Fr equency % of b und le % of root Ex pect ed Act ua l Ex pect ed Act ua l Ex pect ed Act ua l Att ract ed ol be 3.88E -142 395 808 33.3 68.1 4.6 9.5 Repel led yap do/m ak e 1.04E -13 147 70 12.4 5.9 4.6 2.2 et do/m ak e 1.30E -10 193 115 16.2 9.7 4.6 2.8 ver gi ve 2.55E -9 85 37 7.2 3.1 4.6 2.0 konu ş spe ak 8.27E -8 37 9 3.1 0.8 4.6 1.1 de sa y 1.73E -6 57 25 7.2 2.1 4.6 2.0 çı k go/c ome out; emer ge 9.32E -6 51 23 4.3 1.9 4.6 2.1 an lat ex pl ain 1.43E -5 14 1 1.2 0.08 4.6 0.3 geç pa ss 1.44E -4 36 15 3.0 1.3 4.6 2.0 ça lış work 2.07E -4 45 22 3.8 1.9 4.6 2.3 bı ra k le av e 9.25E -4 16 4 1.3 0.3 4.6 1.2

28

Philip Durrant Ta ble 15: As soc iation s and rep ul sion s betw een thr ee-morp heme b und le s and verb r oot s Ro w no . Bu nd le Att ract ed Repel led Root Tr an sl ation Fis her’s te st ( p ) Root Tr an sl ation Fis her’s te st ( p ) 15.1

SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I

ol be 3. 88 E-14 2

yap et ver konu

ş

de çık anlat geç çalış bıra

k do/m ak e do/m ak e gi ve spe ak sa y go/c ome o ut; emer ge ex pl ain pa ss work leav e 1.04E -13 1.30E -10 2.55E -9 8.27E -8 1.73E -6 9.32E -6 1.43E -5 1.44E -4 2.07E -4 9.25E -4 15.2 PAS S-Il SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> et yap bıra k yar at ver do/m ak e do/m ak e le av e cr eat e gi ve 2.06E -24 4.57E -15 2.59E -9 6.34E -7 4.37E -4 çı k çalış go/c ome o ut; emer ge work 1.57E -6 1.8E -4 15.3 NE G-mA SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> ol be 2.11E -62 yap et konu ş ça lış do/m ak e do/m ak e spe ak work 4.67E -8 4.46E -5 1.40E -4 5.67E -4 15.4 PAS S-Il SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> yap et do/m ak e do/m ak e 9.89E -23 3.27E -8 çı k go/c ome o ut; emer ge 4.16E -4

Formulaicity in an agglutinating language

29

15.5

SUB-<y>AcAK POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I

sağl a pr ov ide/ obt ain 5.77E -4 ça lış work 3.77E -3 15.6

SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> ACC-<y>I

konu ş bı ra k spe ak le av e 9.08E -6 7.43E -3 ol be 5.27E -3 15.7

SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> DAT-<y>A

konu ş spe ak 3.32E -4 15.8 PO SS-<y>A NE G-mA AOR -z et do/m ak e 1.67E -5 15.9 SUB-DIK POS.3PL -lArI<n> AC C-<y>I 15.10

SUB-DIK POS.3-<s>I<n> DAT-<y>A

ol be 2.06E -23 et yap do/m ak e do/m ak e 1.13E -5 8.56E -3

30

Philip Durrant

– Both bundles which include the passive marker PASS-Il (rows 15.2 and 15.4) are attracted to the roots yap (‘do’/‘make’) and et (‘do’/‘make’) and repelled by the root çık (‘go’/‘come out’; ‘emerge’3).

– Both bundles which include the two-morpheme combination SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> and do not include the passive morpheme PASS-Il (rows 15.6 and 15.7) are attracted to the root konuş (‘speak’). Indeed, were the analysis ex-tended to the 11th most frequent bundle (SUB-mA POS.3-<s>I<n> GEN-<n>In),

which also includes this pair, it would been seen that the same root is again attracted. This root is not attracted to any other bundles.

These considerations suggest that some of the associations seen here hold not between the roots and these specific three-morpheme bundles (which are, like the N-grams of traditional corpus linguistics, mere analytical conveniences), but rather between the roots and more abstract grammatical categories. Any full usage-based description of the likely grammar of this language user would therefore need to determine the level of abstraction at which particular lexical-syntactic associations are most salient.

5 General discussion

This study set out to explore the extent and types of high-frequency morphological patterns that can be found in the input of a language user (specifically, the input of a reader of online newspapers over a six month period) in Turkish. As was noted in the introduction, none of the analyses used here can present a complete picture of formulaicity. However, taken together, they do suggest a number of important conclusions.

First, the corpus evidenced both a small number of very high frequency complex words, and a large range of very low frequency words. Such a distribu-tion fits comfortably within the dual-route processing model put forward for Finnish by Niemi et al. (1994). However, formulaic patterning does not stop at the word level. A morphological model which takes seriously the usage-based claim that frequency affects representation will need to take into account the following facts:

3 Note that in Turkish, intransitive verbs can be used in the passive, where it gives the meaning of something being ‘generally done’.