MARKET REACTION TO DEATHS OF FOUNDERS AND NON-FOUNDING

EXECUTIVE FAMILY MEMBERS IN FAMILY FIRMS

The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences

of

İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University

by

EZGİ ARSLAN

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE

THE DEPARTMENT OF

MANAGEMENT

İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY

ANKARA

I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for degree of Master of Science in Management.

Asst. Prof. Dr. Ayşe Başak Tanyeri Supervisor

I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for degree of Master of Science in Management.

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Aslıhan Salih Examining Committee Member

I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for degree of Master of Science in Management.

Asst. Prof Dr. Burze Yaşar Examining Committee Member

Approval of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences

Prof. Dr. Halime Demirkan Director

iii

ABSTRACT

MARKET REACTION TO DEATHS OF FOUNDERS AND NON-FOUNDING

FAMILY MEMBERS IN FAMILY FIRMS

Arslan, Ezgi

M.S., Department of Management

Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Ayşe Başak Tanyeri

August 2016

This thesis empirically investigates how markets react to uncertainty regarding the separation of control and ownership in family firms. I examine the market reaction to deaths of founders or non-founding executive family members. Deaths of executive family members (including founders) create uncertainty regarding the future distribution of control rights and the sale of block-holds. My sample spans 88 death notices of founder or non-founding family members from 69 firms across 16 countries. Average abnormal return on the day of the death notice of executive family members is statistically significant and positive at 0.75 percent. The positive and significant market reaction to executive family member deaths indicates that the expected dilution in family control is perceived as positive news. Furthermore, cross-country market reaction to deaths of executive family members is more pronounced (but the difference proves insignificant) as the protection of shareholder rights decrease. Markets reaction to news about future dilution of family control in firms headquartered in countries, where minority shareholder rights are less protected, is more positive.

iv

ÖZET

PİYASANIN AİLE ŞİRKETLERİNDE GERÇEKLEŞEN KURUCU VE AİLE ÜYESİ

ÖLÜMLERİNE TEPKİSİNİN ANALİZİ

Arslan, Ezgi

Yüksek Lisans, İşletme Bölümü

Tez Yöneticisi: Yrd. Doç. Dr. Ayşe Başak Tanyeri

Ağustos 2016

Bu tezde aile şirketleri özelinde yönetim ve hissedarlığa ilişkin belirsizliklere hisse senedi piyasasının verdiği tepki incelenmiştir. Çalışmada 16 ülkeden 69 aile şirketindeki 88 kurucu ve aile üyesinin ölüm haberlerinin hisse fiyatlarını nasıl etkilediğini araştırdım. Şirket kurucuları ve aile üyelerinin vefatının haber olarak piyasaya düştüğü gün aile şirket hisselerinin ortalama anormal getirisi istatiksel olarak anlamlı ve % 0,75 olarak bulunmuştur. Yüzde 0.75 olarak gerçekleşen getiri, aile üyelerinin vefatının ortaklık yoğunlaşmasını azaltacağına ve ortaklık yapısındaki olası değişimin piyasa tarafından olumlu algılandığına işaret etmektedir.

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost, I offer my sincerest gratitude to my supervisor, Asst. Prof. Ayşe Başak Tanyeri, who has supported me throughout my thesis with her patience, invaluable guidance and exceptional supervision. She consistently allowed this paper to be my own work, but steered me in the right direction whenever she thought I needed it. I would also like to thank Assoc. Prof. Aslıhan Salih and Asst. Prof. Burze Yaşar as my thesis examining committee members who made valuable comments. I would also like to acknowledge my husband, Volkan Alp for his support and patience. I also thank my parents, Beyhan and Osman Arslan, and my sister, Merve Arslan, for their encouragement and support.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT………..iii ÖZET………..iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……….………v TABLE OF CONTENTS………..…..vi LIST OF TABLES………...viii LIST OF FIGURES………..……..ix CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………1CHAPTER II: LITERATURE REVIEW………..4

2.1 Family Firm Context………...4

2.2 Incentive Conflict Between Managers Who are not Block-holders and Owners……….5

2.3 Managers as a Key Asset……….………7

2.4 Incentive Conflict Between Powerful Manager and Shareholders……….……….…..8

2.5 Studies on Executive Block-Holder Deaths in US and Around the World...12

CHAPTER III: SAMPLE……….……….………15

3.1 Constructing the Sample………...15

3.2 Compiling Stock Returns and Market Index Returns………..18

3.3 Measures of Protection of Shareholder Rights and Managerial Entrenchment……….……….……19

vii

CHAPTER IV: METHODOLOGY………24

CHAPTER V: EMPIRICAL RESULTS………30

CHAPTER VI: ROBUSTNESS TESTS………..43

CHAPTER VII: CONCLUSION………48

REFERENCES……….……….51

viii

LIST OF TABLES

1. Studies on Executive Block-Holder Deaths in US and Around the World...12 2. Distribution of Countries in Terms of Events and Firms..………..…...18 3. Country and Index Matching………..19 4. Development Level, Antidirector Right Index and Oppressed Minority

Mechanism Existence of Countries………22 5. Market Reaction to Deaths of Founders or Non-Founding Executive Family

Members in Family Firms………..32 6. Market Reaction to Deaths of Founder and Non-Founding Family Members

in Family Firms by Status and Legal Protection Level………35 7. Cross-Sectional Regressions to Measure the Market Reaction Variety

Accordance with the Legal Protection Level of Shareholders and Entrenchment Level of Managers………..….42 8. Market Reaction to Deaths of Founder and Non-Founding Family Members

in Family Firms by Status and Legal Protection Level (with Market-Adjusted Model)……….……….……..44 9. Market Reaction to Deaths of Founder and Non-Founding Family Members in Family Firms by Status and Legal Protection Level (with OLS Market Model)……….45 10. Cross-Sectional Regressions to Measure the Market Reaction Variety Accordance with the Legal Protection Level of Shareholders and Entrenchment Level of Managers (with Market-Adjusted Model)……….…….46 11. Cross-Sectional Regressions to Measure the Market Reaction Variety

Accordance with the Legal Protection Level of Shareholders and Entrenchment Level of Managers (with OLS Market Model)………47

ix

LIST OF FIGURES

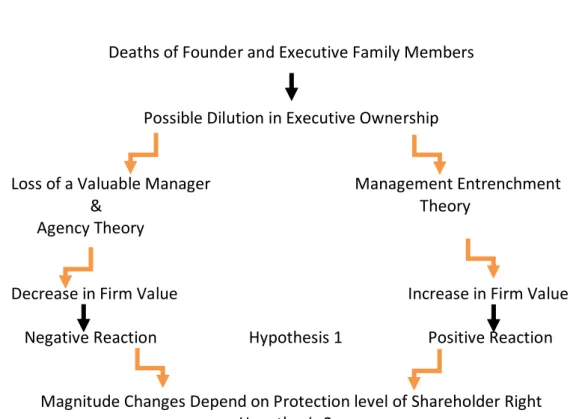

1. Summary of Literature Review with Hypothesis 1……….11

2. Summary of Literature Review with Hypothesis 2………....14

3. Event Timeline……….24

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

This thesis empirically investigates how markets react to uncertainty regarding the separation of control and ownership in family firms. Deaths of founders and executive family members result in uncertainty about who will manage the family firm. Furthermore, surviving relatives of the deceased may choose to sell their shares (usually block-holds) which will create uncertainty regarding how block-holds of shares will fare in the future. On one hand, markets may perceive the separation of control and ownership as bad news for the company. Separation of control and ownership results in agency costs. Managers may use the sources of the firm for his own interest at the expense of shareholders. Furthermore, shareholders may choose to undertake the monitoring and bonding costs to limit wasteful activities (Berle and Means, 1932; Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Hence, market might perceive the

increased probability in separation of ownership and control to hurt firm value and react negatively. On the other hand, markets may regard the separation of control and ownership as good news. Fama and Jensen (1983) find that managers who are also block-holders (whose ownership stake is larger than 5 percent) have “excessive” power since they cannot be monitored. This excessive power enables manager to make decisions for his interest rather than the firm's and slows the growth of the

2

firm (Wright et al., 1996; Stulz, 1988). Thus, investors might perceive the dilution in the power of the manager as good news and react positively.

I examine the market reaction to deaths of founders or non-founding executive family members by conducting an event study analysis. I also investigate factors that might affect the market reaction. My sample consists of 88 deaths of founder or non-founding family members in 69 firms across 16 countries. Average abnormal returns on the day of the death notice of executive family members is statistically significant and positive at 0.75 percent. The positive and significant market reaction to executive family member deaths indicates that markets perceive the expected dilution in family control as positive news. The result supports the “powerful manager problem” espoused by Fama and Jensen (1983).

La Porta et al. (1999) report that family firms compromise more than half of the 20 largest public firms in 27 countries. Family firms represent about 55 percent of publicly held firms in the US and generate nearly 60 percent of employment

(Villalonga and Amit, 2006). Furthermore, about 40 percent of Fortune 500 (Gersick et al., 1997) and one third of the S&P 500 firms are family firms (Anderson and Reeb, 2003). These figures highlight the importance of family firms in the economy and provide the basis for my sampling choice.

I also investigate how the market reaction to executive family member deaths differs across countries. The degree to which legal codes protect minority

shareholders may shape market reaction to deaths of executive family members (La Porta et al., 1998). My sample consists of 88 events across 16 countries. Thus, I can

3

measure whether and how investors in different countries with different legal codes react to deaths of founder or non-founding executive family members. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first study that investigates cross-country differences in market reaction to executive deaths. Furthermore, cross-country market reaction to deaths of executive family members is more pronounced as the protection of shareholder rights decrease. Markets reaction to news about future dilution of family control in firms headquartered in countries, where minority shareholder rights are less protected, is more positive. However, the results prove insignificant.

Regression results show that market reaction to deaths of founder managers is more positive than deaths of other executive family members. This finding contrasts with the findings of Morck et al. (1988), Anderson and Reeb (2003), Adams et. al. (2009), and Villalonga and Amit (2006) who find that firms with founder-executives create extra wealth to all shareholders.

The paper is organized as follows. In section I, I discuss the theoretical framework. In section II I explain my sampling frame and how I construct the sample. I discuss the research method in section III. In section IV, I discuss the results in full-sample and subsamples. In section V, I undertake robustness tests. Conclusions are drawn in section VI.

4

CHAPTER II

LITERATURE REVIEW AND TESTABLE HYPOTHESIS

2.1 Family firm context

Anderson and Reeb (2003a) define family firm as a firm in which founder or descendants hold shares or are present on the board of directors. Anderson and Reeb (2004) improve the definition of family firms as a firm if at least one of the following conditions hold: family members own at least 10 percent ownership stake of the family firm, family members are executives in the firm, a family member is the CEO, the deceased executive’s position is taken over by another family member; and family members play active role in the top management team. Madden et al. (2012) classify family firms if the family owns at least 10 percent of equity and at least one family member is in the top management team.

Abovementioned definitions suggest that family members are major shareholders in family firms. Empirical research finds that family members hold significant ownership stake in family firms. La Porta et al. (1999) examine public family firms across 27 countries and find that, on average, 53 percent of the shares are owned by family members. Using a sample of 190 public companies from US, Madden et al. (2012) show that family member ownership is, on average, 54 percent. In addition

5

to ownership, Sirmon and Hitt (2003) suggest that family members are also top-level managers in the firm. These studies indicate that family members are both managers and block-holders in family firms. Hence, I take deaths of family members as events, which create uncertainty regarding the control and ownership structure of family firms.

Death of an executive family member creates uncertainty regarding the future distribution of control rights and the sale of block-holds. In a world where Modigliani-Miller (1958) assumptions of no information asymmetry and no incentive conflicts hold, changes in control and ownership concentration do not affect the value of the firm. Hence, changes in the control or ownership

concentration should not create a significant market reaction.

H0: Market Reaction to Death of Executive Family Members will be insignificant.

2.2 Incentive Conflict between Managers who are not Block-Holders and Owners Family firms provide unique settings to study the relation between firm value and ownership concentration of managers since managers of family firms are also major shareholders in the company. Agency theory suggests that separation of ownership and management of a company reduces firm value because managers acting on their best interest may not always serve the best interest of shareholders (Berle and Means, 1932; Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Agency costs are a natural outcome of agency relations. Jensen and Meckling (1976) define agency relationship as a contract under which the agent (owners) hires the principal (manager) to perform managerial activities on behalf of the agent.

6

The agent does not always act in the best interest of the principal since he derives utility both from increasing firm value and from activities that increase his utility at the expense of shareholders. Main reasons underlying the conflict between

manager and stockholder are the resource usage problem (Murphy, 1985; Jensen, 1986) and effort problem (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). A manager needs to devote significant effort to settle corporate activities up. If the manager is not a major shareholder, he might exert as much effort to serve the best interest of the

shareholders. A manager is allowed to use firm resources to increase the wealth of shareholders, whereas he may choose to spend resources to serve his own interest. Thus, manager might choose to exert effort and firm resources to increase his own utility at the expense of shareholders’ benefit.

Difference in time horizon of investment is another source of agency cost (DeAngelo and Rice, 1983; Bryd et al. 1998). Since firms have infinite lives, shareholders prefer long-term investments, which provide long-term cash inflow. Managers are

concerned with firm profitability during their employment. Thus, managers prefer to make short-term profitable investments instead of investments that will increase the value of the firm in the long run.

Agency theory predicts that as an outcome of conflict between manager and owner, agency costs arise and these costs decreases the value of the firm. Since managers of family firms are majority shareholders, agency costs may be less pronounced in family firms compared to non-family firms.

Slovin and Sushka (1993) find that death of owner manager reduces equity ownership concentration. The equity may be redistributed due to the takeover of

7

the stocks or the heirs may share the deceased’s equity. The death of executive block-holders tends to result in acquisition bids, and thus to decrease the

ownership concentration of managers. Hence, deaths of executive family members increase the separation of control and ownership.

Markets may react negatively to deaths of founders or executive family members because it may increase agency cost of the firm. In line with agency theory, Morck, Shleifer and Vishny (1988) and McConnell and Servaes (1990) find a positive relationship between ownership concentration and the ratio of total market value of a firm to replacement value of its assets (Tobin’s Q). The results indicate that high ownership concentration increases firm value. These empirical studies provide support the theoretical implication of agency theory, which suggest that the separation of control and ownership decreases firm value.

H1A: Market Reaction to Death of Executive Family Members will be Negative.

2.3 Managers as a Key Asset

A top manager who decides on financing and investment is crucial in determining profitability and hence value of the firm (Bertrand and Schoar, 2003; Jenter and Lewellen, 2011).Previous studies document that CEO turnovers significantly affect operating profitability of the firm (Bennedsen et al., 2007; and Bennedsen et al., 2010; Denis and Denis,1995; Huson et al., 2004; Perez-Gonzales, 2006). Losing a top manager leads to a decrease in firm performance. Bennedsen et al. (2010) find that CEO deaths cause a decline in operating profitability, investment and sales growth.

8

Decline in profitability and growth entails decrease in firm value. Thus, death of a top manager decreases firm value.

H1A: Market Reaction to Death of Executive Family Members will be Negative.

Abovementioned theories that perceive death of executive family members as bad news imply that value of the family firm will decrease with the death of an owner manager. Thus, these theories would both predict negative abnormal returns on the date of the founder or executive family members’ death. I cannot distinguish

whether the negative reaction is a result of the possible dilution in managerial ownership concentration or due to losing a valuable executive.

2.4 Incentive Conflict between Powerful Manager and Shareholders

Agency theory asserts that the separation of control and ownership creates agency costs because of the divergence in interest of managers and shareholders.

However, Shleifer and Vishny (1989) suggest that there are other market-based control mechanisms to monitor managers and prevent them from wasting firm resources. Monitoring mechanisms such as managerial labor market (Fama, 1980), banks (Stiglitz, 1986), capital markets (Easterbrook, 1984) and the market for corporate control (Jensen and Ruback, 1983) decrease agency costs. On the other hand, if a manager is entrenched in the firm, he may ignore the market-based monitoring mechanisms. According to Shleifer and Vishny (1989), a manager is entrenched when it is costly to replace him. Thus, the entrenched manager can spend firm resources to serve his own interest at the expense of shareholders. As a

9

result, the conflict of interest between entrenched manager and shareholders would be an important problem which decreases firm value.

Management entrenchment theory suggests that the higher managerial entrenchment the firm is subject to, the higher the agency cost is. The theory conjectures that entrenched managers make decisions in line with their own risk appetites, interests and beliefs. Thus, they use “private benefits of control” at the expense of minority shareholders (Barclay and Holderness, 1989). Shleifer and Vishny (1989) suggest that entrenched managers often require higher wages and costly settlements from shareholders. This individual-serving or family-serving decision making might include nepotism in hiring process or channeling the cash flow to departments which serve managerial interest. Consequently, entrenched managers hurt firm value.

Nguyen and Nielsen (2012) propose block-ownership as a way of managers to entrench themselves. Salas (2010) measures the market reaction to unexpected senior executive (Chairman, CEO and President) managerial entrenchment is likely when the board consists of shareholders. Fama and Jensen (1983) suggest that managerial ownership entrench managers and entrenched managers cause high managerial consumption and low probability of bidding by outside agents. These two results decrease firm value. In the theoretical model of Stulz (1988),

concentrated managerial ownership decreases firm value by restricting takeovers or making takeovers more costly. Morck, Shleifer and Vishny (1988) find that as

ownership concentration increases Tobin’s Q decreases (the ration of total market value of a firm to replacement value of its assets) when managerial stake is

10

between 5 and 25 percent. These studies support the theoretical implication of management entrenchment theory.

Slovin and Sushka (1993) find that after the deaths of managerial block-holders, managerial ownership concentration falls. Since high managerial ownership

entrench managers, decrease in managerial ownership causes decline in managerial entrenchment. Thus, according to management entrenchment theory, death of an owner manager in a family firm needs to enhance firm value. Nguyen and Nielsen (2012) find that each additional 10 percent ownership of managers cause 1 percent points higher stock price reaction to death of owner-managers. Johnson, Magee, Nagarajan and Newman (1985) observe positive market reaction to death of founder CEOs. The authors interpret this result as lowering management entrenchment increases the value of the firm.

In addition to block-ownership, Both Berger et al. (1997) and Graham (2000) show that CEO age and tenure are proxies of managerial entrenchment. The longer a manager works in a firm, the more control he gains over managerial procedures and, as a result, it becomes costly to replace him. Hence, managerial entrenchment is more pronounced as the tenure of managers is higher. Age is a sign of experience and positively related with tenure (Salas, 2010). Thus, as age increases managers are likely to be entrenched. Salas (2010) discusses that being a founder can also be used as a proxy for managerial entrenchment. Founder of a company is in a unique position in the hierarchy of the firm (Morck et al., 1988). Founders have an

11

(Morck et al., 1988). Johnson et al. find that death of founders creates positive market reaction.

Management entrenchment theory suggests that highly entrenched managers can hurt firm value due to the agency-cost caused by decision making to serve their own risk appetites, interests and believes. As an outcome of managerial ownership, managerial entrenchment increases. Entrenchment increases the agency costs and decreases firm value. Because family firms are controlled by majority shareholders, they are more subject to agency problems which arises because of the incentive conflict between powerful manager and shareholders. Deaths of founder or

executive non-founding family members, which cause possible separation of control and ownership, decrease managerial entrenchment, and hence increase firm value.

H11B: Market Reaction to Death of Executive Family Member will be Positive.

Deaths of Founder and Executive Family Members

Possible Dilution in Executive Ownership

Loss of a Valuable Manager Management Entrenchment

& Theory

Agency Theory

Decrease in Firm Value Increase in Firm Value

Negative Reaction Hypothesis 1 Positive Reaction Figure 1: Summary of Literature Review with Hypothesis 1

12

2.5 Studies on Executive Block-Holder Deaths in US and Around the World Table 1: Summary of Related Literature

Paper Sample Method Results

Johnson, Magee, Nagarajan, and Newman (1985) NSYE/AMEX (53) 1971-1982 Sudden Executive Deaths Event study that uses OLS market

model and calculates 3 day

CAR (0,+2)

Deaths of founder create positive AR (3.50%) and deaths of non-founder create negative AR (-1.16%). Worrell, Davidson, Chandy and Sharon (1987) NSYE/AMEX (127) 1967-1981 Death of key executive officers

Event study that uses OLS market

model and calculates event

day AR (t = 0)

Event day returns is 0.13% and not significant.

The reaction to chairman deaths and CEO deaths

are both significant. Slovin and Sushka (1993) NSYE/AMEX/NASDAQ (85) 1973-1989 Insider Block-holders Deaths

Event study that uses OLS market

model and calculates 2 day

CAR(-1,0)

Two-day abnormal return for full sample is 3.01%, for founders 4.01% and for non-founders 2.12%; all significant. Salas (2007) CRSP data (184) 1988-2005 Sudden Deaths of Executives

Event study that uses OLS market

model and calculates 2 days

CAR (0, +1)

Event day returns is -0.07% and not significant.

Bennedsen and Gonzales and Wolfenzon (2010) KOB (5,091) 1994-2004 Death of CEOs and

Family Members

Regression with asset, ROA, firm

age, asset growth, sales growth, ROA

CEO and family member of CEOs’ deaths affect

firm profitability. Nguyen and Nielsen (2010) NSYE/AMEX/NASDAQ (149) 1991-2008 Sudden Block-holder Deaths

Event study that uses OLS market

model and calculates 3 days

CAR(-1,1)

Event day returns is -0.74% and insignificant

(3-day CAR -1.22% and insignificant). Nguyen and Nielsen (2012) NSYE/AMEX/NASDAQ (385: 115 are sudden) 1991-2008 Block-holder Deaths

Event study that uses OLS market

model and calculates 3 days

CAR(-1,1)

3-day CAR -1.22% and insignificant. Madden, Kellermanns, Eddleston and Patel (2012) CRSP data (190; 84 are family firms)

1972-2003 Sudden Deaths of

Executives

Event study that uses market

model and calculates 2 days

CAR (-1,0)

Average 2day CAR is -0.76%. Sudden executive

death leads to greater negative stock reaction

13

Agency theory suggests that managers are more inclined to make self-serving decisions when control and ownership is separated. In this setting, decrease in managerial ownership causes significant drop in firm value since it increases the agency cost. On the other hand, if shareholders have right to challenge decisions of managers, managers do not hurt firm value by making individual-serving decisions. The separation of control and ownership does not increase agency cost enough to hurt the firm value significantly. Thus, separation of control and ownership in a firm, which operates in an environment with higher legal protection of investors, does not drastically change the value of the firm.

Deficiency of protective legal rules and regulations for a potential minority shareholder makes family firms subjected to the incentive conflict between

powerful manager and minority shareholders. If minority shareholders do not have right to challenge decisions of entrenched managers, managers may use resources of the firm to serve their own interest instead of shareholders’ interest. It increases the agency cost and causes the value of the firm to drop. Hence, in this setting, a decrease in ownership concentration creates positive value for the company, since it decreases managerial entrenchment. On the other hand, entrench managers do not make individual-serving decisions if minority shareholders have right to

challenge managers’ decisions. Entrenched managers theoretically do not increase agency cost enough to cause significant decrease in firm value. Thus, decrease in managerial ownership concentration in a firm, which operates in an environment with higher legal protection of investors, does not drastically change the value of the firm.

14

To sum up, the value of a firm will change with a decrease in ownership

concentration especially in countries where small investor rights are not protected. Owner manager deaths in family firms, which operate in an environment with lower legal protection of investors, will generate stronger reaction than deaths in

environment with more protection of investors since owner manager deaths reduces managerial ownership concentration (Slovin and Sushka, 1993). I predict that markets, where minority shareholder rights are protected less, react more compared to markets, where rights of shareholders are protected strongly.

H21: Market Reaction to Deaths of Founder and Non-Founding Family Member in

Countries with Low Protection of Minority Shareholders’ Rights is Greater in Magnitude Than Market Reaction in Countries with High Protection of Minority Shareholders’ Rights.

Deaths of Founder and Executive Family Members

Possible Dilution in Executive Ownership

Loss of a Valuable Manager Management Entrenchment

& Theory

Agency Theory

Decrease in Firm Value Increase in Firm Value Negative Reaction Hypothesis 1 Positive Reaction

Magnitude Changes Depend on Protection level of Shareholder Right Hypothesis 2

15

CHAPTER III

SAMPLE

3.1 Constructing the Sample

My sample consists of death announcements of founders and family members who hold managerial positions in family firms. First of all, I compile the sample of family firms. Lee (2006) defines family firms as firms in which a family either has significant ownership or has managerial control. I rely on “The World’s 250 Largest Family Businesses” list (Family Business magazine, 2004) compiled by Family Business magazine to identify family firms around the world.

Family Business Institute finds that less than one third of the family firms survive after the founder passes away and only 12 percent of family firms make it to third generation (Family Business Institute). It means that if I could find two obituary notices of managers from one family firm, this firm represents at most 12 percent of the family firms. Since I use death announcements from world’s largest family firms as an event, my sample spans survived firms. Hence, survival bias is

pronounced for my sample. Thus, I am aware that my results are not representative of all family firms.

16

I eliminate private companies from the list since market reaction to deaths in those firms cannot be measured. I use Bloomberg to determine whether a family firm is public. If I could not find sufficient information in Bloomberg, I refer to firms’ websites. “The World’s 250 Largest Family Businesses” list spans 150 public family firms.

Second, I refer to firms’ websites to identify the name of the founder and founding family. Then, I use Lexis-Nexis guided search to find obituary notices of deceased founders or non-founding family members. I select “obituary notice” news and search name of founders to find news of deceased. If I find any death

announcement with the name of the founder, I read the announcement carefully to be sure that the deceased is the founder. After careful reading of obituary notices, I note the date of the death. I check the date at least from two news sites that announce the death.

To find death announcements of non-founding family members, I select “obituary notice” news and search founding family name and firm name. After identification of names of descendants, I cross check their names from firms’ websites and family trees. The filter produces 123 founder and non-founding executive deaths who work in 90 publicly traded family firms.

Finally, I compile stock price information from Bloomberg. I could only find daily stock prices of 69 firms. My final sample includes 88 founder and executive family member death announcements in these 69 firms. It spans 34 years from June 1981 to January 2015. 50 death announcements are between 2002 and 2015; and 38

17

deaths announcements are between 1981 and 2001. I also check news about the firm around event date in order to eliminate confounding events such as another death or mergers and acquisitions. There is no confounding event for any of these 88 deaths. Consequently, the sample spans 88 deaths in 69 publicly traded

companies headquartered in 16 countries. Table 2 lists the country of firms.

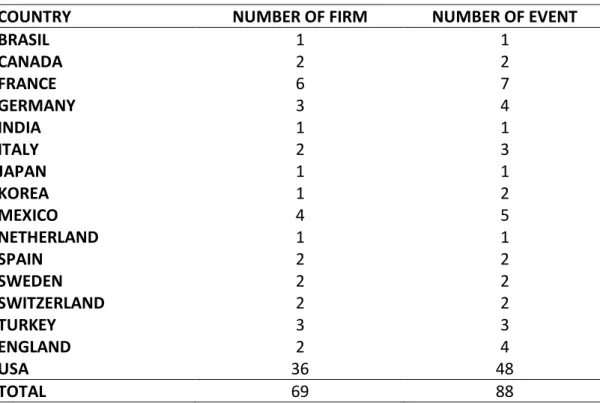

Table 2: Distribution of Countries in Terms of Events and Firms

COUNTRY NUMBER OF FIRM NUMBER OF EVENT

BRASIL 1 1 CANADA 2 2 FRANCE 6 7 GERMANY 3 4 INDIA 1 1 ITALY 2 3 JAPAN 1 1 KOREA 1 2 MEXICO 4 5 NETHERLAND 1 1 SPAIN 2 2 SWEDEN 2 2 SWITZERLAND 2 2 TURKEY 3 3 ENGLAND 2 4 USA 36 48 TOTAL 69 88

Appendix 1 presents my death announcement sample summary. For example, Samuel Walton is the founder of Walmart, which is headquartered in US. He died on April 5, 1992 and there is no other death announcement from Walmart in my

sample. Chung Ju-Yung is the founder of Hyundai, which is headquartered in Korea. He died on March 21, 2001 and my sample also spans death announcement of his descendant, Chung Mong Hun who passed away on August 4, 2004.

18

3.2 Compiling Stock Returns and Market Index Returns

This study analyzes the daily abnormal returns and cumulative abnormal returns in a three-day event window of deaths of executive family members in family firms. I obtain daily adjusted stock prices of firms (Pi,t) from Bloomberg. Bloomberg defines daily adjusted price as the closing stock price which is adjusted for dividends and stock splits. Daily stock return is defined as the daily percentage change in adjusted stock price. Equation 1 illustrates daily stock return (Ri,t) calculation.

𝑅𝑖,𝑡 = 𝑃𝑖,𝑡−𝑃𝑖,𝑡−1

𝑃𝑖,𝑡−1 (1)

I also compile daily market index value in each country from Bloomberg and

calculate daily market index returns using Equation 1. As a market benchmark, I use country specific indexes shown in Table 3.

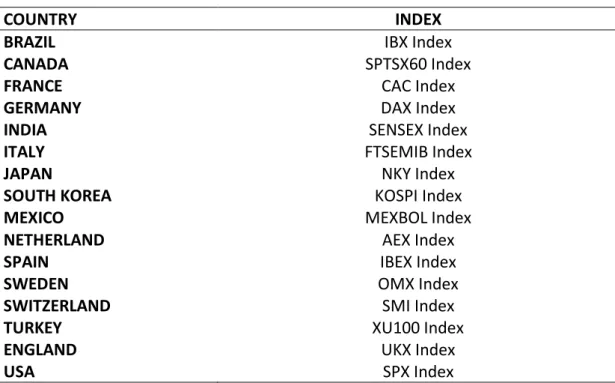

Table 3: Country and Index Matching

COUNTRY INDEX

BRAZIL IBX Index

CANADA SPTSX60 Index

FRANCE CAC Index

GERMANY DAX Index

INDIA SENSEX Index

ITALY FTSEMIB Index

JAPAN NKY Index

SOUTH KOREA KOSPI Index

MEXICO MEXBOL Index

NETHERLAND AEX Index

SPAIN IBEX Index

SWEDEN OMX Index

SWITZERLAND SMI Index

TURKEY XU100 Index

ENGLAND UKX Index

19

3.3 Protection of Shareholder Rights and Managerial Entrenchment

Managers are block-holders by definition in family firms. Managerial ownership creates managerial entrenchment and hurts firm value. Nevertheless, the effect of managerial entrenchment might diverge across countries according to the legal protection level of shareholders. Hence, my sample that is gathered from 16 countries is very suitable to test whether different level of investor protection creates difference in market reaction to executive block-holder deaths. Managerial death potentially dilutes managerial entrenchment since it may decrease

managerial ownership.

La Porta et al. (1998) show how differences in legal codes across countries result in differences in investment behavior. Minority shareholders in countries, which provide higher legal protection to shareholders, can involve more to the decision process of the firm. Hence, shareholders in these countries can invest in firms regardless of the ownership structure of the firm or power of managers since their rights are protected against managers and dominant shareholders. On the other hand, investors in countries with less legal protection of minority shareholders hesitate to invest in firms in which managers are entrenched because minority shareholders cannot challenge self-serving decisions of managers. Managers may use their power to waste sources of the firms for their own interest that might hurt firm value. Thus, dilution of managerial entrenchment affects firm value. These effects are more pronounced in markets with less legal protection.

I use four variables as proxy to classify countries in which shareholders’ rights are protected with laws and regulations. First, I look at the development stage of

20

countries as indication of whether investors’ rights are protected. When determining the development level of countries, I refer to Dow Jones Indexes Country Classification System (2011) in which countries are classified based on Market and Regulatory Structure in addition to Trading Environment, and

Operational Efficiency. According to this classification system, developed markets are defined as “markets which are the most accessible to and supportive of foreign investors with a high degree of consistency across these markets”, whereas

emerging markets (developing markets) are defined as “markets which have typically less accessibility relative to developed markets, but demonstrates some degrees of openness”. (Dow Jones Indexes, September 2011) Because the

classification includes regulatory structure analysis, I identify developed countries as markets where shareholder rights are protected.

Second proxy for legal protection of shareholders is to be headquartered in US. Villalonga and Amit (2004) find that shareholders of firms that are traded in US stock markets are protected at a higher level compared to shareholders traded in Asian economies (Claessens et al., 2002), Swedish economy (Cronqvist and Nilsson, 2003), or emerging markets (Lins, 2003). Thus, I conjecture that investors of US firms are better protected through laws and regulations.

Third, I use antidirector right index, which La Porta et al. (1998) develop to classify countries in terms of how strongly legal system favors minority shareholders against managers and block-holders. La Porta et al. (1998) form this index by aggregating six shareholder rights, to measure how strongly the legal system protects minority shareholders’ rights. Antidirector right index ranges from 0 to 6 and La Porta et al.

21

(1998) assign numbers to countries based on protection of six main shareholder rights.

La Porta et al. form the index (1998, 1123):

by adding one when the country permit shareholders to mail their proxy vote to the firm, shareholders are not required to deposit their shares prior to the general shareholders’ meeting, cumulative voting or proportional

representation of minorities in the board of directors is allowed, an oppressed minorities mechanism is in place, the minimum percentage of share capital that entitles a shareholder to call for an extraordinary shareholders’ meeting is less than or equal to 10 percent, or shareholders have preemptive rights that can be waived only by a shareholders’ vote.

I use the antidirector right index numbers which is assigned by La Porta et al. (1998).

Finally, I use the existence of oppressed minority mechanism as a proxy for existence of investors rights.

Oppressed minority mechanism is defined by La Porta et al. (1998) as

the existence of law or commercial code that grants minority shareholders either the right to challenge the decisions of management or the right to step out of the company by requiring the company to purchase their share when the object to certain changes.

I collect the data of the existence or deficiency of the oppressed minority mechanism from the study of La Porta et al., (1998), Law and Finance.

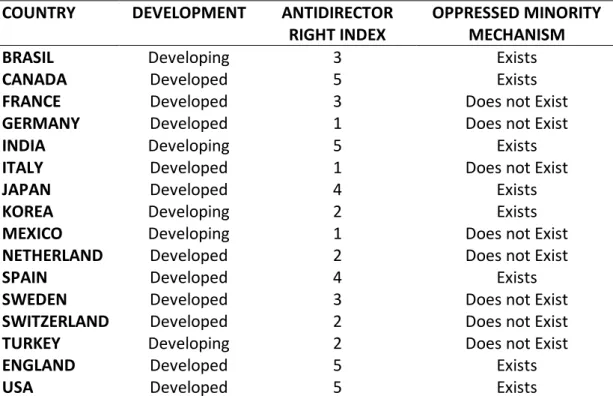

Table 4 summarizes development level, antidirector right index, and existence of oppressed minority mechanism of each country. First column shows development level of each country. Second column illustrates antidirector right indexes that are assigned by La Porta et al. (1998). Index ranges from zero to six. My sample spans countries with antidirector right index that ranges from one to five. Last column shows whether legal code covers oppressed minority mechanism.

22

Table 4: Development Level, Antidirector Right Index and Oppressed Minority Mechanism Existence of Countries

COUNTRY DEVELOPMENT ANTIDIRECTOR RIGHT INDEX

OPPRESSED MINORITY MECHANISM

BRASIL Developing 3 Exists

CANADA Developed 5 Exists

FRANCE Developed 3 Does not Exist

GERMANY Developed 1 Does not Exist

INDIA Developing 5 Exists

ITALY Developed 1 Does not Exist

JAPAN Developed 4 Exists

KOREA Developing 2 Exists

MEXICO Developing 1 Does not Exist

NETHERLAND Developed 2 Does not Exist

SPAIN Developed 4 Exists

SWEDEN Developed 3 Does not Exist

SWITZERLAND Developed 2 Does not Exist

TURKEY Developing 2 Does not Exist

ENGLAND Developed 5 Exists

USA Developed 5 Exists

I also use three variables as proxy to identify firms where managerial entrenchment is pronounced. Founder status is the first proxy for managerial entrenchment. To measure the effect of management entrenchment on the stock price reaction, founder of a company is in a unique position in the hierarchy of the firm (Morck et al., 1988). Founders have an excessive control over their firm and they are too entrenched to be removed (Morck et al., 1988). Thus being the founder of the company is another way of being an entrenched manager.

Second proxy is the number of years a manager works in the firm (tenure).

Managers who work many years in a company gain more power over processes of the firm and it becomes costlier to replace them. Third proxy of managerial

entrenchment is age, since it is a sign of experience, and experienced managers have more power over the firm. Berger et al. (1997) and Graham (2000) find that both age and tenure can be used as a proxy of management entrenchment. To

23

identify the tenure of the deceased, I search for recruitment and retirement date of managers. I find these dates and age of deceased from newspaper articles and obituary notices. I cross-check dates and other information from at least two newspaper articles.

24

CHAPTER IV

RESEARCH METHOD

I use event study method to measure markets reaction to deaths of founder or an executive family member. Event study measures abnormal returns by differencing realized returns from expected returns. Realized return is the daily percentage change in closing stock price which is adjusted for dividends and stock splits. Expected return is defined as the theoretical return of stocks if the event had not taken place. Thus, abnormal returns indicate the market reaction to the certain event.

Day 0 is the event day which is the first trading day after the death announcement. My event window starts 20 trading days prior to deaths announcement of executive family members and ends 20 days after the deaths. Estimation window starts 272 days before announcements and ends 20 days before announcements. Figure 1 plots the event timeline.

𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐨𝐰 𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐨𝐰

T0 = -272 T1 = -20 0 T2 = +20

25

I use three models to calculate expected returns. I use mean-adjusted model, market-adjusted model and Ordinary Least Square (OLS) market model (Brown and Warner, 1985). Mean-adjusted model finds expected return of a stock by averaging daily returns of the stock in the estimation period (-272, -20). Expected return calculation in mean-adjusted model is shown in Equation 2.

𝐸(𝑅𝑖) = 1

252 𝑅𝑖,𝑡

−20

𝑡=−272 (2)

where 𝐸(𝑅𝑖) is the expected return of stock i and 𝑅𝑖,𝑡 is the realized return of stock i

at time t.

In market-adjusted model, expected return at time t is the return of market index at time t. Expected returns in market-adjusted model is illustrated in Equation 3.

𝐸(𝑅𝑖,𝑡) = 𝑅𝑚 ,𝑡 (3)

where 𝐸 𝑅𝑖,𝑡 is the expected return of stock i at time t, 𝑅𝑚 ,𝑡 is the return of market index at time t.

OLS market model finds expected return of a stock using Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). I compute 𝛼 𝑖 and 𝛽 𝑖 coefficients by regressing realized returns on market

index. 𝛽 𝑖 is the stock’s sensitivity to market index. For firms with more than one

death announcement, I run regression for each event and compute 𝛼 𝑖 and 𝛽 𝑖

separately.

Equation 4 shows how expected returns are calculated in OLS market model. 𝐸(𝑅𝑖,𝑡) = 𝛼 𝑖+ 𝛽 𝑖𝑅𝑚 ,𝑡 + 𝜀𝑖,𝑡 (4)

26 E(𝜀𝑖,𝑡) = 0, Var(𝜀𝑖,𝑡) = 𝜎𝜀2𝑖

where 𝐸 𝑅𝑖,𝑡 is the expected return of stock i at time t, 𝑅𝑚 ,𝑡 is the return of

market index at time t.

Abnormal returns in each event is the difference between realized stock returns and expected returns of stocks. Equation 5 shows how abnormal returns are calculated in mean-adjusted model.

𝐴𝑖,𝑡 = 𝑅𝑖,𝑡− 𝐸(𝑅𝑖) (5)

where 𝑅𝑖,𝑡 is the realized return of stock i at time t and 𝐸(𝑅𝑖) is the expected return of the stock i. Expected return in mean adjusted model is the same for all event period days.

In market adjusted model, abnormal stock return is the difference between realized stock return and market index return at time t. Equation 6 shows how abnormal returns are calculated in market-adjusted model.

𝐴𝑖,𝑡 = 𝑅𝑖,𝑡− 𝑅𝑚 ,𝑡 (6)

where 𝑅𝑖,𝑡 is the realized return of stock i at time t and 𝑅𝑚 ,𝑡 is the market index return of market m at time t.

OLS market model calculates abnormal returns by subtracting realized stock returns from expected returns. Equation 7 illustrates the calculation in OLS market model.

27

where 𝐴𝑖,𝑡 is the abnormal return of stock i at t, 𝑅𝑖,𝑡 is the realized return of stock i

at time t, and 𝑅𝑚 ,𝑡 is the market index return of market m at time t.

I calculate cross sectional average of abnormal returns as is illustrated in Equation 8.

𝐴 𝑡 = 1

𝑁𝑡 𝐴𝑖,𝑡

𝑁𝑡

𝑖=1 (8)

where 𝐴 𝑡 is the cross sectional average abnormal returns at time t, and 𝑁𝑡 is the number of events in the sample. The number of events in the full sample, 𝑁𝑡 is 88.

I also calculate cumulative abnormal return to measure market reaction to deaths in a multi-day interval. Since death is an unpredictable and sudden event, I start the CARs on the first trading day after the death announcement. Equation 9 shows the three-day cumulative abnormal returns.

𝐶𝐴𝑅 0,+2 = +2𝑡=0𝐴 𝑡 (9)

I test for the significance of abnormal returns and cumulative abnormal returns. If markets react to deaths of founder and managerial family members, abnormal and cumulative abnormal returns need to be significantly different than zero. I test the null hypothesis that abnormal return on day 0 is not significantly different than zero. The test statistic is the ratio of average abnormal return on the event day to its estimated standard deviation as shown in Equation 10.

𝑡 = 𝐴 0

28

where t is test statistic, 𝐴 0 is the abnormal returns at day 0 and 𝑠 𝐴 0 is the

estimated standard deviation. The test statistic is distributed Student-t. (Brown and Warner, 1985) Equation 11 shows how standard deviations are calculated.

𝑠 𝐴 𝑡 = 𝐴 𝑡 − 𝐴 2 𝑇1 𝑡=𝑇0 𝑇1− 𝑇0− 1 (11) where 𝐴 = 1 𝑇1−𝑇0 𝐴 𝑡 𝑇1 𝑡=𝑇0 (12)

where 𝐴 𝑡 is abnormal return at time t, 𝐴 is the average abnormal return at

estimation window, 𝑇0 is the starting day of estimation window, and 𝑇1 is the

starting day of event window.

I also calculate cumulative abnormal return to test multi-day interval market reaction to deaths. I test the significance of the market reaction in a three-day interval using test statistic shown in Equation 13 (Brown and Warner, 1985).

𝑡 0,+2 = 𝐶𝐴𝑅 0,+2 +2𝑡=0𝑠 𝐴 𝑡 2 1

2 (13)

where 𝐶𝐴𝑅 0,+2 is a three-day cumulative abnormal return between day 0 and 2. I

assume that the test statistic is unit normal.

I use regression analysis to examine sources of variability in market reaction to founder and executive family member deaths. My main specification regresses abnormal returns on three independent management entrenchment proxy variables (founder, age of deceased, and tenure of deceased) and three minority shareholder rights proxy variables (developmental status of the country, oppressed

29

minority mechanism, and anti-directory rights index). Equation 14 illustrates the regression.

𝐴𝑅𝑖 = 𝛼𝑖+ 𝛽𝐹𝑀𝑖+ 𝛽𝐷𝑃𝑖 + 𝜀𝑖 (14)

where 𝑀𝑖 presents the level of entrenchment of manager in event i; 𝑃𝑖 illustrate

whether minority shareholder rights are protected against managers and dominant shareholders in a country or not.

Founder variable is a dummy variable and equals to 1 when deceased is founder of the family firm. Age and tenure are discrete variables which represent the age of deceased at time of death; and the number of years that the deceased works in the family firm, respectively. In each regression, I use at most one of the managerial entrenchment variables. For example, if I use founder status variable in one regression, I do not use any other managerial entrenchment proxy (age or tenure) in the same regression.

As a proxy of minority shareholder rights protection, I use development level of countries, existence of oppressed minority mechanism; and (high or low) anti-director right index. I use these variables to measure how strongly minority shareholder rights are protected in a country where the deceased’s firm is headquartered. Development level of country variable is a dummy variable and equals to 1 when the country is categorized as developed. Oppressed minority mechanism variable is a dummy variable and equals 1 when law or commercial code grants minority shareholders either the right to challenge the decisions of management or the right to step out of the company by requiring the company to

30

purchase their share when the object to certain changes (La Porta et al., 1998). Anti-director right index variable is a dummy variable and equals 1 when anti-Anti-director right index is 4, 5 or 6 (La Porta et al., 1998). In regression analysis, 𝑃𝑖 equals 1 when minority shareholder rights are protected against managers and dominant

shareholders. In each regression, I use at most one of the minority shareholder right protection variables (In some regressions, I regress abnormal returns only by using one management entrenchment proxy). For example, if I use oppressed minority mechanism variable in one regression, I do not use development level variable or antidirector right index variable in the same regression, however I might use managerial entrenchment variables in the same regression.

31

CHAPTER V

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

This chapter discusses the empirical results on how markets react to the death announcements of the founder or an executive family member. First, I analyze both the daily abnormal returns for three days, from t=0 to 2, and three-day-cumulative abnormal returns in the full sample. Then, I examine the event day abnormal returns in the subsamples. The subsamples are classified according to shareholder rights protection (development level of country, US or non-US origin, existence of oppressed minority mechanism, and high or low anti-director right index of the country). Finally, I run a cross-sectional regression of daily average abnormal returns on management entrenchment proxies (FOUNDER, AGE and TENURE), and variables used as a proxy for shareholder rights protection (DEVELOPMENT, OPPRESSEDMINORITY and ANTI-DIRECTORRIGHTS).

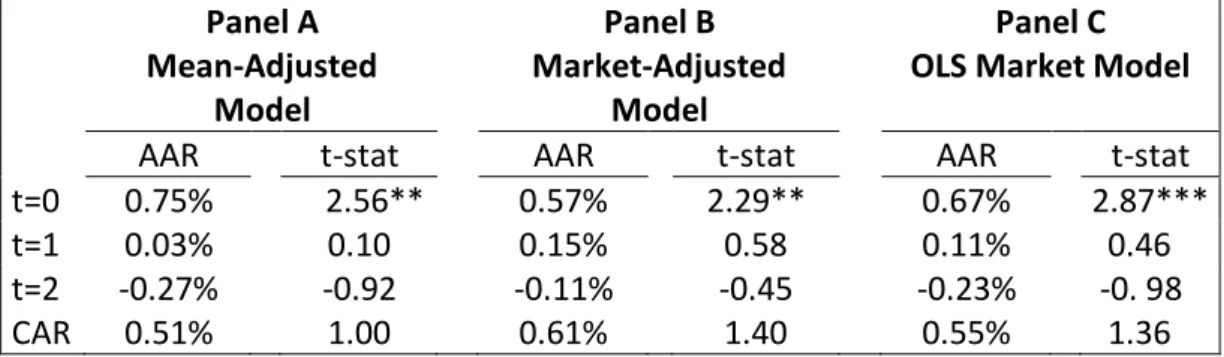

Table 5 reports average abnormal returns on the first trading day after founder or executive family members passes away. Panel A reports event study results of mean-adjusted model, Panel B reports results of market-adjusted model and Panel C presents results of OLS market model. First column of each panel reports average abnormal returns for the first three days following the death announcements (from

32

t=0 to 2) and the three-day cumulative abnormal returns. Second column of each panel presents t-statistics. Standard deviations of mean-adjusted model, market-adjusted model and OLS market model are 0.29 percent, 0.25 percent, and 0.23 percent, respectively.

Table 5 Market Reaction to Deaths of Founders or Non-Founding Executive Family Members in Family Firms

Panel A Mean-Adjusted Model Panel B Market-Adjusted Model Panel C OLS Market Model AAR t-stat AAR t-stat AAR t-stat t=0 0.75% 2.56** 0.57% 2.29** 0.67% 2.87*** t=1 0.03% 0.10 0.15% 0.58 0.11% 0.46 t=2 -0.27% -0.92 -0.11% -0.45 -0.23% -0. 98 CAR 0.51% 1.00 0.61% 1.40 0.55% 1.36 ** denotes statistical significance at 5 percent level

*** denotes statistical significance at 1 percent level

Table 5 summarizes daily abnormal returns in the event period (0, 2). Panel A, panel B and panel C reports results for mean-adjusted model, market-adjusted model and OLS market model, respectively. Average abnormal stock returns are provided under the columns labeled as AAR and t-statistics are presented under the second column of each panel. As a CAR, three-day (0, 2) cumulative abnormal returns of each method are given. Expected returns are calculated using the estimation period, t = -20 to -272, t = 0 stands for the event day which is the day founders or non-founding family members pass away.

Event day average abnormal return is positive and significant at 0.75 percent using the mean-adjusted model. The average abnormal returns calculated by using market-adjusted model and OLS market model are also positive and significant at 0.57 and 0.67 percent, respectively. Since the average abnormal return of the event

33

day is significantly different than zero, I reject the first null hypothesis that market does not react significantly to deaths of founder or executive family member.

Event day average abnormal return is significantly positive for all three event study methods. Markets react positively to death of a founder or a non-founding

managerial family member in family firms. We can interpret this evidence within the context of how managerial ownership in the family firms affects the wealth of shareholders. This result is consistent with the view of management entrenchment theory. Managerial block-holdership causes undervaluation in family firms because of the agency cost which arise as a consequence of the conflict of interest between family shareholders and minority shareholders. Although agency problem related costs might affect event day abnormal returns negatively, positive abnormal returns suggest that powerful (entrenched) manager effect is more dominant. Markets perceive possible dilution in managerial ownership as good news.

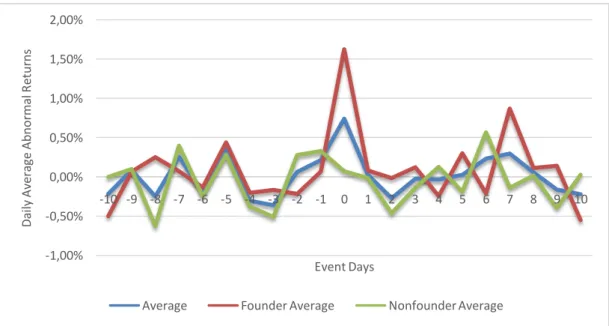

Table 5 shows that post-event period, t=1 to 2, and three-day CARs prove

insignificant. Figure 4 plots the daily abnormal returns in the 20-day interval around the death announcements. The plot visually shows that positive and significant market reaction takes place only on the event day. Figure 4 indicates that market reactions to deaths of executive family members are immediate. Thus, I will concentrate on the event day reaction.

34

Figure 4: Daily Average Abnormal Returns around Death Notices

Deaths of executive family members cause possible dilution in managerial ownership (Slovin and Sushka, 1993). Decrease in managerial ownership causes decline in managerial entrenchment. Dilution in managerial entrenchment is

expected to create more reaction in environments where managerial entrenchment related problems are pronounced more. Since marked-based monitoring

mechanisms (managerial labor market, banks, capital markets, and the market for corporate control) do not prevent entrenched manager increasing agency costs, shareholders in environment where minority shareholder rights are not (or less) protected are subject to managerial entrenchment related problems more than shareholders in markets where minority shareholder rights are protected. Managerial entrenchment will decrease firm value more in environments where shareholder rights are not protected. Thus, I expect markets with less minority shareholder rights protection to react more to executive family member deaths compared to markets with high shareholder protection.

-1,00% -0,50% 0,00% 0,50% 1,00% 1,50% 2,00% -10 -9 -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 D ai ly Av er age Abnor m al R et ur ns Event Days

35

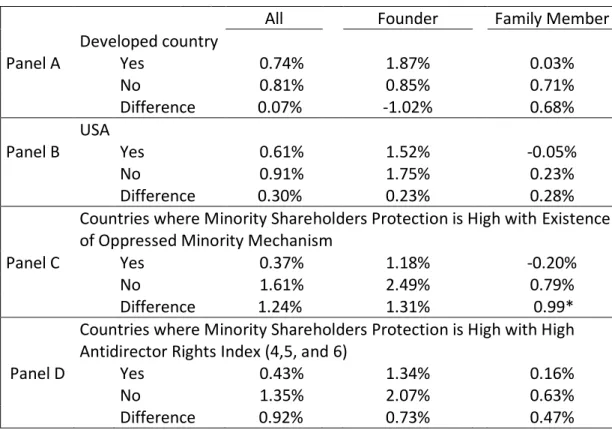

I investigate how protection of shareholder rights in different countries affect the market reaction to the death of founder and non-founding family members in subsamples. I use four proxies (Developed countries; US market; markets where Oppressed Minority Mechanism exists; and countries with high anti-director right index) to classify countries as having strong protection of minority shareholder rights. Table 6 presents event day abnormal returns in mean-adjusted model. First column shows results of the full sample; second column presents results in the subsample of founder deaths and third column reports results in the subsample of executive non-founding family member deaths.

Table 6 Market Reaction to Deaths of Founder and Non-Founding Family Members in Family Firms by Status and Legal Protection Level

All Founder Family Member

Developed country Panel A Yes 0.74% 1.87% 0.03% No 0.81% 0.85% 0.71% Difference 0.07% -1.02% 0.68% USA Panel B Yes 0.61% 1.52% -0.05% No 0.91% 1.75% 0.23% Difference 0.30% 0.23% 0.28% Countries where Minority Shareholders Protection is High with Existence of Oppressed Minority Mechanism

Panel C Yes 0.37% 1.18% -0.20%

No 1.61% 2.49% 0.79%

Difference 1.24% 1.31% 0.99* Countries where Minority Shareholders Protection is High with High Antidirector Rights Index (4,5, and 6)

Panel D Yes 0.43% 1.34% 0.16%

No 1.35% 2.07% 0.63%

Difference 0.92% 0.73% 0.47% * denotes statistical significance at 10 percent level

Table 6 shows the average abnormal returns on the event day. I use mean-adjusted model to compute expected returns. First column reports full sample results;

36

second column reports founder subsample results; and third column reports non-founding executive family member subsample results.

In Panel A, events are classified according to development level of country in which firm of deceased is headquartered. I use Dow Jones Country Classification System to label each country as developed or developing country (Dow Jones Indexes,

September 2011), since regulatory structure is a determining factor to categorize countries. There are 11 developed countries (with 76 events) and 5 developing countries (with 12 events) in the sample.

I use developing countries as proxy for the environment where rights of minority shareholders are protected less. Average abnormal return in developed countries is 0.74 percent, and average abnormal return in developing countries is 0.81 percent. The magnitude of market reaction to deaths of executive family members is larger in developing countries compared to reaction in developed countries. Sign and magnitude of market reaction to executive deaths in developed and developing countries is in line with my hypothesis that markets with strong shareholder rights protection react more to deaths of executive family members than markets with less rights protection. However, average abnormal return of the deaths in

developed countries is not statistically different from average abnormal return of deaths in developing countries.

Market reaction to deaths of executive family members in developed countries is also smaller than deaths of executive family members in developing countries. On the other hand, deaths of founders in developed countries unexpectedly cause more reaction. This indicates that, from minority shareholder perspective, death of

37

founders in developed countries is perceived as better news than death of founders in developing countries. As Schwert (1985) suggests, some founders might be entrenched while some other founders can be an important asset for the company. Villalonga and Amit (2006) provide evidence that family ownership with founder-executives creates additional value for all shareholders. Market reaction differences are not statistically significant across the subsamples.

I also use US markets as a proxy for environment with stronger legal protection of investors. Villalonga and Amit (2004) find that shareholders of firms that are traded in US stock market are more protected compared to firms traded in Asian

economies (Claessens et al., 2002), in Sweden (Cronqvist and Nilsson, 2003), or in emerging markets (Lins, 2003). Thus, I conjecture that shareholder rights are protected better in US. My sample spans 48 death announcements from firms located in US and 40 death announcements from firms headquartered in other countries. Average abnormal return in US is 0.61 percent, and average abnormal return in other countries is 0.91 percent. Result of this analysis points that US investors react less to executive family member deaths than other markets. Since I use US markets as an environment with high minority shareholder rights protection, results are in line with my hypothesis but the difference prove insignificant.

In Panel C, I analyze the difference in markets reaction to executive deaths

according to whether there is oppressed minority mechanism in the country where the family firm is incorporated. The mechanism gives minority shareholders “either the right to challenge the decisions of management or the right to step out of the company by requiring the company to purchase their share when the object to

38

certain changes” (La Porta et al., 1998). Thus, I use countries with oppressed minority mechanism as a proxy of environment with high protection of minority shareholder rights. The sample includes 61 death announcements in countries where oppressed minority mechanism exists. Average abnormal return in countries where oppressed minority mechanism exists is 0.37 percent, and average abnormal return in other countries is 1.61 percent. Executive family member deaths in

environment, where oppressed minority mechanism does not exist, create more positive reaction than executive family member deaths in environment where oppressed minority mechanism exists. Thus, there is a small evidence to support that existence of oppressed minority mechanism cause less market reaction.

Panel D, in Table 6, presents markets reaction to executive family member deaths in countries with high (4, 5, and 6) director right index and low (1, 2, and 3) anti-director right index (La Porta et al., 1998). Anti-anti-director right index categorizes countries based on how strongly rights of minority shareholders are protected against managers and dominant shareholders. Higher protection of minority shareholder rights means higher anti-director rights index (4,5 and 6) and less protection of minority shareholder rights is assigned lower anti-director rights index (0, 1, 2 and 3). The sample covers 58 death notices in countries with high (4,5 and 6) anti-director right index and 30 death notices in countries with low anti-director right index. Average abnormal return in countries with high anti-director right index is 1.43 percent and average abnormal return in low anti-director index is 1.35 percent. Results suggest that the magnitude of market reaction to deaths in countries where the rights of minority shareholders are protected more is low.

39

In line with my second hypothesis, subsample event study results show that markets react less to death announcements of executive family members in environments with higher judicial protection of shareholder rights compared to death announcements in countries with lower judicial protection of shareholders. Market-adjusted model and OLS market model give qualitatively similar results. Nevertheless, since those markets reaction do not differ significantly, I fail to reject the null hypothesis that markets reaction significantly differs based on how strongly shareholders’ rights are protected.

Unbalanced subsample sizes might be an issue which affect the significance. For example, my sample spans 88 death announcements; 76 of which are in developed countries, whereas 12 of which are made in developing countries.

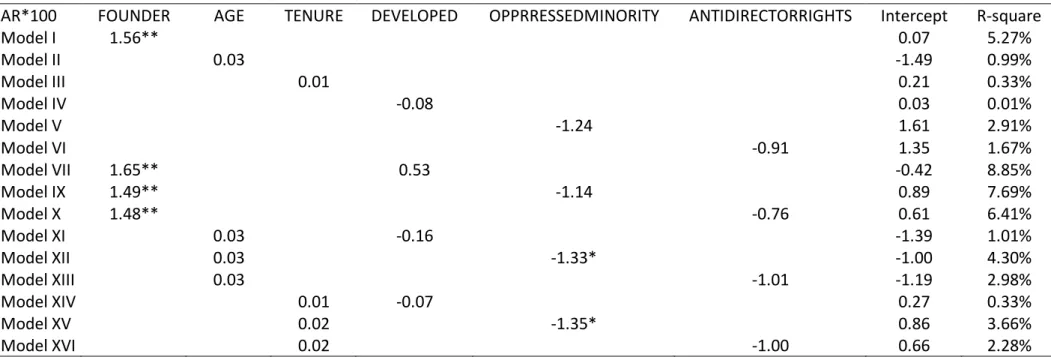

Table 7 shows the results of weighted least square regressions in which event day abnormal return in percent (with mean-adjusted model) is the dependent variable and independent variables measure legal protection level of shareholders and entrenchment level of managers. Table 7 reports the result of cross-sectional regression in which the dependent variable is the event day abnormal return for 88 death announcements. I use three variables (FOUNDER, AGE, and TENURE) as a proxy for management entrenchment (Berger et al., 1997; Graham, 2000; Morck et al., 1988). FOUNDER is a dummy variable, which equals one when the deceased is the founder. AGE is the age of deceased at time of death. TENURE is the number of years that the deceased works in the family firm. If managerial entrenchment depresses firm value, markets should react positively to death announcements, which dilute managerial entrenchment. Management entrenchment variables

40

(FOUNDER, AGE, and TENURE) are positively related with managerial entrenchment (Berger et al., 1997; Graham, 2000; Morck et al., 1988). Thus, deaths of executive family members is expected to be positively related with the share price reaction since deaths dilute managerial entrenchment.

The coefficients of management entrenchment variables are positive which implies that deaths of entrenched managers are perceived as positive news. Among

managerial entrenchment variables, FOUNDER is the only statistically significant variable. It indicates that market perceives deaths of a founder in family firms as better news than deaths of a non-founding family member. Morck et al. (1988) suggests that founder status is indication of entrenched managers. According to management entrenchment theory, managerial entrenchment increases agency costs and thus reduces the value of the firm. Since deaths of founders dilute managerial entrenchment, it decreases the exposure of minority shareholders to the conflict between powerful manager and minority shareholders; and hence increases the value of the family firms.

I specify three variables to measure the effect of legal protection of shareholders. First one, OPPRRESSEDMINORITY, is a dummy variable which equals one when law or commercial code grants minority shareholders either the right to challenge the decisions of management or the right to step out of the company by requiring the company to purchase their share when the object to certain changes (oppressed minority mechanism). Second one, ANTIDIRECTORRIGHTS, is also a dummy which takes the value one when legal code is strongly in favor of minority shareholder rights against managers or majority shareholders (anti-director rights equals to 4,5

41

or 6). Last one, DEVELOPMENT, is a dummy which equals one when the firm operates in developed countries. To sum, shareholder rights protection variables are one when shareholder rights protection is high in an environment.

Dilution in managerial entrenchment should matter more in countries where minority shareholder rights are protected less. Deaths of executive family members cause possible dilution in managerial entrenchment by decreasing the managerial ownership concentration (Slovin and Sushka, 1993). Thus, market reaction to executive family member deaths is expected to be more positive in environments with low protection of minority shareholder rights compared to market reaction in environment with high protection of shareholders.

In regression analysis, coefficients of DEVELOPMENT, OPPRESSEDMINORITY and ANTIDIRECTORRIGHTS are negative. The negative coefficients indicate that markets react more to deaths of founder and non-founding family member in countries with less protection of minority shareholders’ rights than deaths in countries with high protection of minority shareholders’ rights. However, the coefficients of

DEVELOPMENT, OPPRESSEDMINORITY and ANTIDIRECTORRIGHTS, prove insignificant.