T.C.

SELÇUK ÜNİVERSİTESİ

SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ

EĞİTİM BİLİMLERİ ANABİLİM DALI

EĞİTİM PROGRAMLARI VE ÖĞRETİM BİLİM DALI

THE EFFECT OF METACOGNITIVE STRATEGIES ON ATTITUDES,

ACHIEVEMENT AND RETENTION IN DEVELOPING WRITING SKILLS

DOKTORA TEZİ

Danışman

Doç. Dr. Mehmet ÇELİK

Hazırlayan

Osman DÜLGER

ÖZET

Yazmayı geliştirmek dil öğrenmenin önemli ve karmaşık bir bölümünü oluşturmaktadır. Yazma alanında yapılan son araştırmalar biliş ötesi stratejilerin yazma becerilerini geliştirme üzerinde etkili olduğunu göstermektedir. Bundan dolayı biliş ötesi stratejilerin yazma becerilerini geliştirmede tutum, erişi ve kalıcılık üzerine etkisi bu çalışmanın amacını oluşturmuştur.

Çalışma 77 Selçuk Üniversitesi İngiliz Dili Eğitimi Anabilim Dalı öğrencisi üzerinde yürütülmüştür. Araştırmada biliş ötesi stratejiler öğretilen öğrenciler ile geleneksel yöntemlerle öğrenim gören öğrenciler arasındaki farkları bulabilmek için öntest -sontest deseni benimsenmiştir. Bu nedenle rastlantısal atama yoluyla bir deney ve bir kontrol grubu seçilmiştir.

Veri toplamada öğrencilerin erişisi ve öğrenilenlerin kalıcılığını ölçmek için öğrencilere öntest, sontest ve kalıcılık testi olarak yazma değerlendirme sınavı uygulanmıştır. Ayrıca, tutumlardaki değişiklikleri araştırmak için öntest ve sontest olarak bir yazma becerilerine karşı tutum ölçeği uygulanmıştır. Bunun yanı sıra elde edilen verilerle karşılaştırmak üzere öğrencilerle görüşmeler yapılmıştır.

Araştırmanın sonuçları istatistiksel olarak biliş ötesi stratejilerin yazmada erişi ve kalıcılığa katkıda bulunduğunu göstermiştir. Ancak, sonuçlar deney ve kontrol grupları arasında yazmaya karşı tutum bakımından anlamlı farklılıklar göstermemiştir.

ABSTRACT

Developing writing is an important and complex part of language learning. Recent research on writing specifies that metacognitive strategies are found to be effective on developing writing skills. Thus, examining the effect of metacognitive strategies on attitudes, achievement and retention in developing writing skills has been the aim of this study.

The study was conducted totally on 77 first year students of Selçuk University English Language Teaching Department. A pretest-posttest design has been adopted throughout the research to find out the differences between the students that are taught the metacognitive strategies and the students who received instruction through traditional methods. For this purpose, an experimental and a control group have been randomly selected.

In data collection, the students were given writing assessment tests as pretest, posttest and retention test to measure achievement and retention of the things learned. In addition, an attitude toward writing scale was administered to as a pretest and posttest to investigate changes in attitudes. Besides, the students were included in discussions and interviews in an attempt to obtain data to compare the quantitative data obtained.

The results of the research statistically proved the contribution of metacognitive strategies to achievement and retention in writing. However, the results did not display significant differences in attitudes toward writing between the experimental and the control group.

ÖZET ... i

ABSTRACT ...ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ...iii

TABLES... iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... v

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION ... 11. STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM ... 1

THE NATURE OF LANGUAGE LEARNING... 24

LEARNING STRATEGIES... 42

CLASSIFICATION OF LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES ... 52

METACOGNITION ... 66

METACOGNITIVE STRATEGIES... 69

STRATEGY INSTRUCTION... 72

DEVELOPING METACOGNITIVE AWARENESS... 88

WRITING... 90

SOME DISTINCTIVE FEATURES OF WRITING... 92

FUNDAMENTAL VIEWS ON DEVELOPING WRITING SKILLS ... 97

Writing as a product ... 97

Writing as a process ... 98

CONTEMPORARY APPROACHES TO WRITING... 107

INSTRUCTIONAL FACTORS IN DEVELOPING WRITING SKILLS ... 109

WRITING ASSESSMENT ... 116

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN WRITING AND METACOGNITION.. 126

2. RELEVANT RESEARCH ... 130

4. RESEARCH QUESTION ... 142 5. RESEARCH HYPOTHESES... 142 6. ASSUMPTIONS... 143 7. LIMITATIONS... 143 8. DEFINITIONS ... 144

CHAPTER II

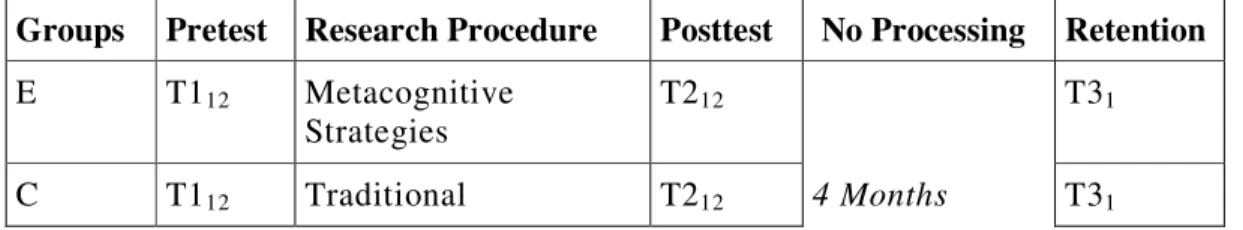

METHODOLOGY ... 145 1. RESEARCH DESIGN ... 145 2. SUBJECTS ... 146 3. PROCEDURES ... 147 4. INSTRUMENTS ... 1484. 1. Writing Assessment Test ... 149

4. 2. Application of the Test ... 149

4. 3. Attitude toward Writing Scale ... 150

4. 4. Data Analysis Techniques ... 151

CHAPTER III

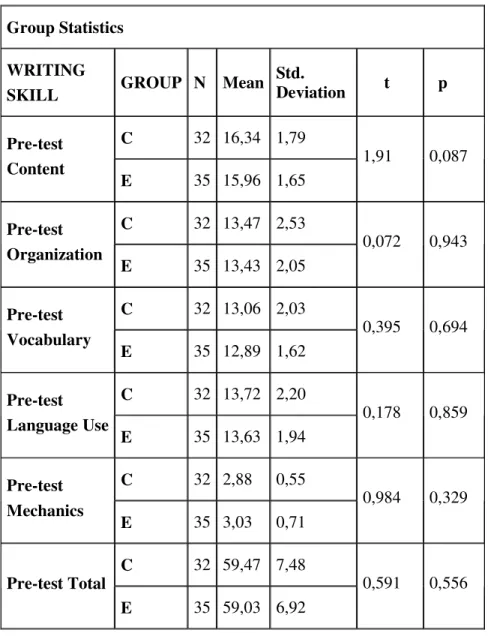

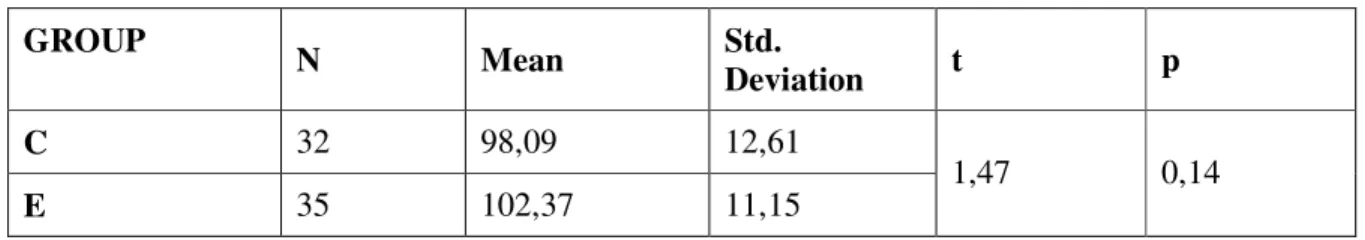

RESULTS... 1521. Achievement Pre-test results of the Experimental and the Control group... 152

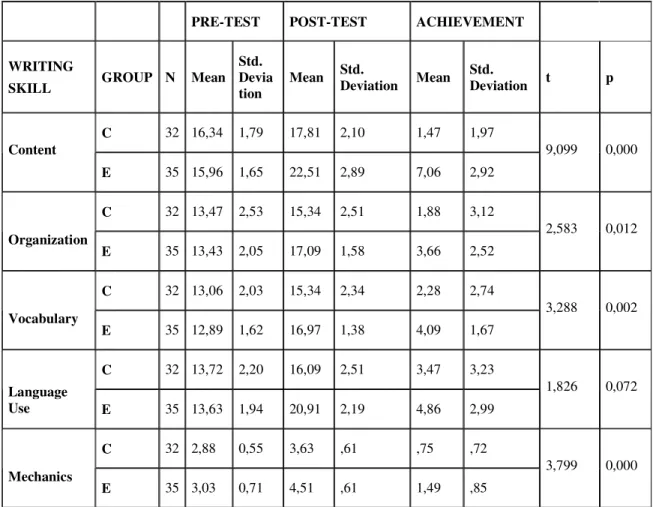

2. Achievement Post-test Results of the Experimental and the Control group ... 154

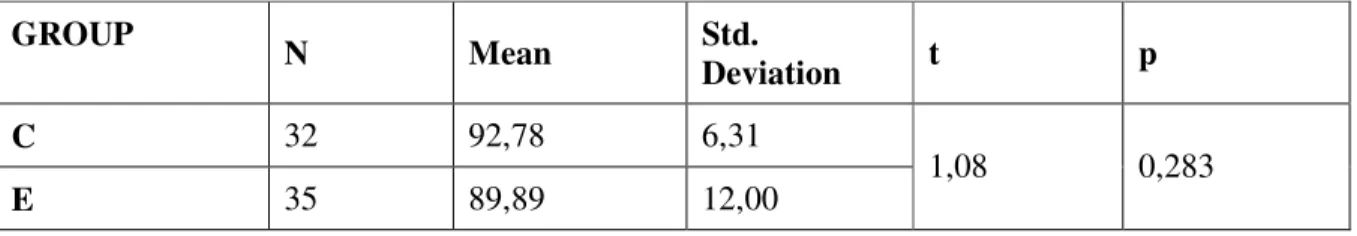

3. Retention Results of the Experimental and the Control group... 156

4. Attitude Pre-test Results of the Experimental and the Control group ... 157

5. Attitude Post-test Results of the Experimental and the Control group ... 158

CHAPTER IV

DISCUSSION and IMPLICATIONS ... 160Discussion of the Hypothesis 1: ... 160

Discussion of the Hypothesis 2: ... 162

CHAPTER V

CONCLUSIONS and SUGGESTIONS... 169

REFERENCES ... 172 APPENDIX A ... 196 APPENDIX B... 197 APPENDIX C... 198 APPENDIX D ... 200 APPENDIX E... 201 APPENDIX F ... 202 APPENDIX G ... 222

TABLES

Table II-1 Experimental Design Used in the Research ... 145 Table II-2 Groups According to the Random Selection ...147 Table III-1 Writing Skills Pre-test Comparison of the Students in the

Experimental Group and the Control Group 153

Table III-2 Writing Skills Achievement Comparison of the Students in the

Experimental Group and the Control Group... 154 Table III-3 Retention Level Comparison of the Students in the

Experimental Group and the Control Group... 156 Table III-4 Pretest Attitude Toward Writing Skills Comparison of the

Students in the Experimental Group and the Control Group... 157 Table III-5 Posttest Attitude Toward Writing Skills Comparison of the

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my gratitude to my advisors Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mehmet ÇELİK from Hacettepe University, and Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ali Murat SÜNBÜL from Selçuk University for their stimulating suggestions and encouragement in all the time of research for and writing of this thesis. They were always there to listen and to give advice.

Besides my advisors, I would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee; Prof Dr. Ömer ÜRE, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Fatih TEPEBAŞILI, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Hasan ÇAKIR, and Assist. Prof. Dr. Kemal GÜVEN for their questions, encouragement, and valuable comments.

I would also like to express my thanks to Dr. Yasin ASLAN for his valuable support and suggestions throughout the study.

I am also greatly indebted to all my colleagues for their contribution to my motivation during the study.

Last, but not least, I thank my wife, my son, and my parents whose patient love, and continuous support enabled me to complete this work.

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

This chapter consists of the statement of the problem, a review of the literature, research questions, hypotheses, limitations, assumptions, definitions and the relevant research on metacognitive strategies in relation to developing writing skills. Review of literature has been designed in an attempt to have a better understanding of the developments, ranging from the more traditional approaches to more contemporary ones, within the educational research area. In this sense, the nature of language learning, learning strategies, metacognitive strategies, some major aspects of writing skills, and the relationship between metacognition and developing writing skills have been the key areas dealt with in this chapter.

1. STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

Every human being, beginning from cradle to grave, is included in some kind of education. Either formally or informally, the need for education has become more significant in an individual’s life recently because education is an indispensable component of shaping the future (Littlejohn, 2001). This is mostly because of the rapid developments and changes experienced, especially in technology and science. Naturally, such kind of changes affect the society, and brings about some prerequisites on the part of the individual in particular, and on the part of the society in general. Thus, the information age of the globalizing world requires an increasing number of intellectually trained members in the society, with much more urgency than the previous ages of agriculture and industry did.

Before going into detail with the descriptions and definitions of education, it is worth reminding the two major divisions about education. In other words, education can

occur either informally or formally in an individual’s life (Smith, 1965). As the name suggests, informal education consists of the knowledge, skills, or experiences gained by the person in an unorganized and unsystematic way (Fidan & Erden, 1987). A person does not need to be included in an institution or a program in this type of education. Surely, every human being is to face some kind of informal education throughout his life. However, it is not the same case with formal education. Formal education is realized mostly as the commonly known type of education provided to students at school. In this sense, education takes place in the form of a planned and institutionalized process (Mercer, 1995). It is true that education is not only limited to school contexts and a person learns things both before and after being included in formal education. However, consistent with the usage in the literature, the term education has been used in this study to refer primarily to formal education instead of focusing on the informally attained experiences.

The literature on education provides us with a vast number of definitions of education. For instance, Blair et al. (1967, p. 280) point out that education is concerned with producing desirable changes in behavior which will carry over into new situations. Similarly, Ertürk (1988, p. 12) regards education as the process of making intentionally desired changes in the individual’s behavior, through his own experience. Education is expected to make some preferred changes on the individual’s behavior. A similar definition by Mercer (1995) proposes that education is primarily a matter of social and linguistic enculturation. Demirel’s (2000, p. 5) definition of education seems to blend the previous two definitions; for him, education is the process of forming behavioral changes, through the individual’s own experience and intentional enculturation. In fact, most of these definitions include similar notions, and can all be traced back to Ralph Tyler’s (1934) writings on education (cited in Travers, 1987). Tyler’s studies on identifying educational objectives are reported to attract many educationalists and curriculum development

specialists. The definitions of education given above seem to represent most of a behavioristic view that focuses primarily on observable behavior change in an individual.

The literature on education offers some other definitions of education that cover areas besides changing behaviors. For instance, Piaget (1970) defined education as a matter of focusing on adapting the child to an adult social environment. Again, another slightly different definition of education can also be made similar to UNESCO’s definition of education as ‘organized and sustained instruction designed to communicate a combination of knowledge, skills and understanding valuable for all activities of life’ (Ikonen, 1999). All things considered, education can be characterized with empowering the learner with a set of functional abilities or knowledge to survive in life.

As can be inferred from the definitions of education presented above, education is far from involving only the memorization of certain mass of knowledge. Besides, a person who passed through the process of education is recognized by having attained abilities for solving problems, for describing and discussing ideas, problems and the relationship between them (Bruner, 1960; Gagne, 1985; Mercer, 1995; Wilson, 2000). Having acquired these abilities, the individual is likely to be more prepared for the society. In this sense, a satisfying understanding of education guides to an individual who is ready to function in the society. Even, parallel to today’s accepted norms of the society, a definition of education might as well address the goal of developing the kinds of thinking skills in individuals to prepare them to contribute to a democratic society (Kuhn & Dean Jr., 2004). Naturally, this planned process of education needs some mechanisms to operate. Curriculum has been the term introduced to operate the system of education according to set goals. Just at this point, the word ‘curriculum’ reminds another term ‘syllabus’. Sometimes curriculum is used interchangeably with syllabus. The similarity of these terms can be observed in the usage of curriculum in the United States of America to refer to the

syllabus used in the United Kingdom (Brown, 2000; Brown, 2001; Finney, 2002). From a functional standpoint, both refer to the same concept as, both curriculum and syllabus are used to indicate designs for meeting the needs of a group of learners in a defined context. Stating the objectives, sequencing, and materials are included in these designs.

However, curriculum and syllabus are not always complete synonyms. A differentiation between curriculum and syllabus can be observed in the usage of syllabus to stand for stating the content of just one area while curriculum suggests a larger framework including the goals, content, teaching-learning experiences and the evaluation of a whole program (Ertürk, 1988; Johnson, 2001; Demirel, 2002). Hence, a curriculum is built on identifying goals in the form of making behavioral changes in the individual included in an educational process. When the goals are stated, content, the necessary educational activities with the methods, techniques and materials are planned to achieve the stated goals. Then, the achievement of goals is evaluated. That is to say, to what degree the educational process has been effective on the learner’s behavior is assessed. According to the assessment results, the curriculum is reviewed and this may lead to some changes in the curriculum if necessary.

In fact, curriculum suggests a continuous process of development where goals, content and teaching-learning experiences are constantly revised. Therefore, designing and developing a curriculum emerges as a much more complex matter than forming a syllabus because in contrast to the syllabus, which is mainly a statement of content of a single area, curriculum is in charge of a wider range of components. From this point of view, the duty of a syllabus can be resembled to the governor’s responsibility of a city and the curriculum to that of a prime minister’s. To state briefly, both curriculum and syllabus are used to describe an inventory that provides the framework of a recommended sequence

(Celce-Murcia, 1991; Johnson, 2001; Finney, 2002). This inventory is used to design courses and teaching-learning experiences in order to fulfill an educational objective.

Designing a curriculum is dependent upon some social, economical, psychological or philosophical factors. That is, it is impossible to prepare a single curriculum suitable for all the societies, or for teaching the same things to everyone. For instance, due to some social, economical or even political reasons, it may not be possible to apply a curriculum designed in the 18th century to teach the same things in the 21st century, or it may not be suitable to apply a curriculum prepared in the USA for American students to teach students in Turkey.

Besides other factors, designing a curriculum requires dealing with learning theories and approaches to instruction. Thus, our understanding of instruction and learning determines the way our curriculum is shaped. Because, determining the types of activities, designing teaching-learning experiences, and even defining the roles of the teacher and the student depend on the underlying learning theory or theories. In other words, especially the why, what, and how of instruction should be explained, based on the principles of the learning theory adopted. For this reason, a curriculum designer must be aware of the strengths and weaknesses of each learning theory to provide optimum benefit from the instruction. However, a curriculum designer does not have to strictly be bound to a single theory, but may be eclectic about the theories.

A number of different theories can be observed within the literature. Although the theories had been introduced by different people and under different names, these theories display some common aspects as well. In view of the developments within the field of psychology, learning theories can basically be divided into two; behaviorist theories and cognitive theories (Demirel, 2002, p. 31).

I will first examine three learning theories informed by the behavioristic approach. Pavlov, Watson, E. C. Tolman, Thorndike, Guthrie, Skinner, Hull were some of the well known scholars who contributed to the development of behaviorism (cited in Kaplan, 1990; Sönmez, 1994). Behaviorism has been the dominant theory of learning until 1950s, and approached learning as a process of forming connections between stimuli and responses. All these theories are known by focusing on the observable behavior, rather than the processes that happen in the mind. To be precise, behaviorism has been based on three basic modes of learning –classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning (Kaplan, 1990):

Classical conditioning is based on Ivan Pavlov’s experiments on animals. Classical conditioning, also known as respondent conditioning, aims at changing the conditions under which an inborn response takes place. Through classical conditioning, animals and human beings learn to respond to new stimuli, similar to their previous natural responses to the stimuli in their environment. Especially some physical and emotional responses are explained. For example, salivation of a dog when it sees meat, or changes in a person’s eye when he encounters light can be observed as a part of classical conditioning. When related to educational contexts, some emotional problems such as a learner’s anxiety about exams are considered to be solved through classical conditioning.

However, as classical conditioning was concerned with reflex behavior related to emotions such as fear or anxiety it couldn’t be possible to explain all kinds of learning in life. In other words, classical conditioning lacked explaining conscious human behavior. In this sense, Thorndike and Skinner’s experiments are regarded as a further step towards explaining behavior. Thorndike viewed learning as a matter of problem solving and proposed that one of the trial and error behaviors constitutes the solution (cited in

Fidan&Erden, 1987). In that case, the behaviors that lead to the solution are expected to become permanent behaviors to be applied when required.

As another major contribution to the behaviorist theory, Skinner’s ‘Programmed Instruction’ proposed that students should be taught in a step-by-step procedure (cited in Kaplan, 1990; Johnson, 2001). This view suggests that the students should be introduced the basic subjects first, and then the harder or more complex points could be presented. Consequently, while classical conditioning focuses on the stimulus-response relationship, behavior is determined by its consequences in operant conditioning. It is accepted that, if the consequences are positive the behavior is likely to reoccur, and if the consequences are less positive the behavior is expected to occur less. Hence, stimulus that follows a given response is controlled (Orlich et al., 1998). For example, if a student answers a difficult question correctly, then the teacher immediately gives the student some praise or some other kind of reward. Rewards become a crucial part of learning activity to reinforce the desired behavior to be permanent. In other words, operant conditioning is interested in an individual’s conscious and intentional behavior distinct from classical conditioning.

As the third basic mode of learning, observational learning investigated how people learn from watching others, while classical conditioning and operant conditioning commonly focused on the observable behaviors. Observational learning has been built on the idea that explaining learning in terms of conditioning is not enough because thinking is not included in learning. To be precise, Bandura’s experiments resulted in the findings that people imitate the models they see around them (cited in Jacobs, 1990). For instance, a student may imitate one of his friends who is mostly appreciated by other people. Not surprisingly, the student is expected to decide on adopting the appreciated behaviors of his friend. Hence, instead of limiting learning to conditioning, the learner’s mind is recommended to be taken into consideration because mind too is active during learning.

Briefly, the behaviorist theories mainly focused on the relationship between the individual and his environment. The environment was given greater attention than the individual. The individual received stimulus and reinforcements from the environment, and he just responded inactively. Application of behaviorist theories to instructional settings suggests focusing on conditioning the learner's behavior where the teacher manipulates the student’s behavior, and the learner is a passive participant in the learning process (Kaplan, 1990; Schuman, 1996; Johnson, 2001). In other words, learning is controlled through manipulation of learning experiences in behaviorism, and it is the teacher’s task to reinforce desirable learning behaviors.

As learning is merely viewed as the acquisition of behavior, limitations in applying behaviorist theories to all situations, especially in recognition of new language patterns by children, have been the basis for criticisms against these theories (Davis, 2003). Whatever goes on in the individual’s mind was not given due attention in behaviorism. Studies carried out in laboratories on animals have not been found adequate in explaining human behavior. Instead, human mind has been regarded as being involved in a series of more complex operations. Such criticisms led to the emergence of some contemporary theories, such as the cognitive theory or the constructivist theory (see below for a discussion); however, it is not right to say that behaviorism is completely inapplicable or has been removed from syllabus considerations. Instead, today some specific methods or techniques of behaviorism are still adopted to be used where needed. For instance, Skinner’s ‘Programmed Instruction’, as an example of behavioral approach to learning, is preferable especially for slow learners, supplementary to regular instruction (see Kaplan, 1990; Joyce&Weil, 1996 for examples).

Cognitive theories form the alternative to those of the behavioristic. Cognitive theorists indicated that learning is a complex process, while behaviorists viewed learning

as a product. To begin with, it is worth citing that the pioneering studies of Piaget paved the way to the research on human cognitive development (Piaget, 1970; Coleman, 1995; Wilson, 2000). In other words, psychologists, who found behaviorism quite unsatisfying, were interested in what goes inside the brain. Certainly, this meant dealing with issues not very easy to observe. Although Piaget’s cognitive development theory is not the single theory to cover the field, it has been accepted as the most inclusive one (Kaplan, 1990).

Following a review of Piaget’s model, four more cognitive theories will be explained. Piaget’s theory is based on child development and learning, and introduces three key concepts –physical knowledge, logico-mathematical knowledge, and social arbitrary knowledge. Physical knowledge includes a child’s knowledge obtained from his interaction with the objects around. The child uses his senses during this interaction that he touches, lifts, looks at, throws, or listens to it. Logico-mathematical knowledge is about inventing relationships between objects and symbols. For instance, a child can classify objects according to some criteria (shape, length, height etc.), compare these objects, or even put them in an order. As the third key concept, social arbitrary knowledge is introduced. This type of knowledge is based on the child’s interaction with other people. Through this interaction the child learns language, rules, and moral values. Piaget’s theory presents child development in stages. These stages are classified into sensorimotor, pre-operations, concrete pre-operations, and formal operations stages:

The sensorimotor stage includes the period between birth and 2 years of age. During this stage the child uses his senses (seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, and tasting) and motor activity. They investigate the world around them. The child finds out that objects and people do not disappear completely but they are only out of sight. As the next stage, preoperational stage encompasses the ages from 2 to 7. It is a longer stage. Besides doing some operations associated with objects (e.g. some mathematical operations) the

child’s observations develop his conceptual awareness. The child can see something occur, store the information about it, and then perform the action using the stored information at a later time. The concrete operational stage includes the time between 7 and 11 years old. In the first two years of elementary school period, most students may be living the end of preoperational stage and enter the concrete operational stage. Introducing abstractions like democracy, justice etc. will probably be still difficult to understand for the students in the concrete operational stage. Instead, solving some problems associated with concrete objects can be the operations these children can tackle with. Finally, at about the ages of 11 or 12 the student enters the formal operations stage. Usually it lasts until the student is 15 years old. The student is expected to go beyond concrete operations and reach the ability to be engaged in abstractions. However, the borders between these stages are not clear cut (Kaplan, 1990). In other words, it is inaccurate to equate these stages of development with exact ages. An individual can enter or go out of a stage at a time different from another person.

The second significant attempt to explain learning from a non-behaviorist perspective in what can be described as cognitivist has been Bruner’s (1960) constructivist theory (see Bennett&Dunne, 1995, and Orlich et al., 1998 for a further discussion). Bruner’s constructivist theory views learning as an active process in which learners construct new ideas or concepts based upon their current/past knowledge. Thus, constructivist view of learning presupposes that learners bring some knowledge and beliefs into the classroom. Hence, things to be learned can be built on the students’ existing knowledge and beliefs. Students discover the world by constructing meanings. In this process, students share their knowledge and experiences with others to optimize learning. The social interaction between the individual and people around him play a significant role in his learning. In other words, the learner’s cooperation with the members of his

community helps him construct his meanings or concepts. The individual is in an active interaction with the environment, contrary to the passive role of the learner in behaviorism. Another significant contribution to the field of learning, which is worth mentioning, has been Gagne’s taxonomy of learning types. Gagne’s hierarchical arrangement of different learning types has been related to the cognitive theory. Robert Gagne (1985) identified eight types of learning that every individual uses:

1- Signal learning is used to refer to learned responses to a signal just like classical conditioning.

2- Stimulus-response learning indicates the precise responses to a discriminated stimulus, as in operant conditioning.

3- Chaining suggests that what is acquired is a chain of more than one stimulus-response connections.

4- Verbal association is used for expressing the chains in a verbal form because the presence of human language makes it possible to construct associations within the learner’s language capacity.

5- Multiple discrimination stage of learning includes the learner’s ability to identify different responses to a number of different stimulus.

6- Concept learning tells about the ability of the learner to make a response that identifies an entire class of objects or events. So, the learner can formulate a common response to a class of stimuli even though the individual members of that class may differ widely from each other.

7- Principle learning regards that a principle is a chain of two or more concepts used to organize behavior and experience.

8- Problem solving is presented as the kind of learning that requires thinking. Previously learned concepts and principles are joined together to focus on an unresolved or ambiguous set of events.

As can be realized from the identified types of learning, the first five of Gagne’s learning types are likely to be included in a behavioristic framework, while the last three types of learning indicate more cognitive dimensions of learning. That is to say, the first five types represent quite lower levels of learning that can be treated in behavioristic terms, and the last three stand for higher levels of learning that can be subjected to cognitive principles.

Another significant theory of learning to attract attention for people relevant to the field of curriculum and instruction has been Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences Theory (Gardner, 1995; Orlich et al., 1998; Saban, 2001; Gardner, 2006). In his book ‘Frames Of Mind’ written in 1983, Gardner opposed the traditional view of single intelligence and proposed that human intellect is better described as consisting of a set of intelligences (cited in Gardner, 1995; Gardner, 2006). To be precise, Multiple Intelligences Theory is against the view that intelligence is a general ability inherent in every person at varying levels. Instead, intelligence is viewed as an ability to process certain kinds of information in the process of solving problems or any activity of production. Thus, a number of intelligences have been proposed (Armstrong, 1994; Gardner, 1995).

Linguistic intelligence allows us to develop semantic storage of information and to explain events. It is also described as the intelligence of words. It is associated with having an oral/auditory component. It is free of physical objects. Logical-mathematical intelligence is mostly interpreted as the traditional intelligence measured in IQ tests. Logical-mathematical intelligence involves the formal operations of symbols according to accepted rules of logic and mathematics. It is the intelligence of numbers and reasoning.

Spatial intelligence is known as the intelligence of pictures and images. In other words, spatial intelligence is the one that enables a person to recognize faces, to find his way home, or to notice details. Musical intelligence involves the capacity to achieve task related to tone, rhythm, and timbre. As the name suggests, it indicates musical capability. Bodily-Kinesthetic intelligence describes the abilities to use the whole body or parts of it to solve a problem or to produce something. It is the intelligence associated with the body and the hands. Interpersonal intelligence is about the relationship between a person and the people in his environment. Having the ability to discern other people’s desires or intentions, and even to take acts based on this knowledge are associated with the interpersonal intelligence of a person. Plainly, it is the intelligence of social interactions. Intrapersonal intelligence is the one that helps a person return to his own feeling life. The person can discriminate among his own feelings, interpret into some other forms to be used later (e.g. for understanding and guiding his own behavior). Basically, it is the intelligence of self-knowledge.

Additionally, subsequent studies resulted in a modification in the number of intelligences, and the ‘naturalistic intelligence’ has been added to the above list (cited in Williams et al., 2002). A person who has naturalistic intelligence is keen on nature, and is aware of his surroundings and changes in his environment. Still, Gardner (2006) states that Multiple Intelligences Theory is a synthesis of work in a number of disciplines, ranging from neuroscience to anthropology, and suggests that findings from brain science and genetics can make critical contributions to the understanding of intelligence and of intelligences. Accordingly, he acknowledges that the number of multiple intelligences can be 8 or 9. Thus, it is not likely to conclude that the Multiple Intelligences Theory has strict and completed boundaries.

Nevertheless, the intelligences covered in this theory highlight operations, actions, or positions an individual takes when he is solving a problem or performing a task in life. By the same token, observing the theory and the implications from the studies on Multiple Intelligences attentively might provide educators, as well as language teachers, with appealing contributions. For example, diversifying the type of learning activities to be included in a curriculum might be of a valuable help in providing the teachers with increased options in instructing their students. Above all, it is not likely to be a disadvantage for a teacher, via benefiting from Multiple Intelligences studies, to know more about his students and to have an idea about the probable differences among his students.

If need be to signal the distinction between behaviorism and cognitivism, one of the main differences between the traditional ‘behaviorist’ theories and the more contemporary ‘cognitive’ theories can be identified by the place of the teacher and the learner in the learning process. That is to say, instruction, designed according to the principles of traditional theories, relies heavily on the teacher, whereas the contemporary theories focus on the learner (Sünbül, 1998; Lunenberg & Korthagen, 2003). The teacher has to be the medium of instruction through explicit teaching, or question-answer drills, and learning is achieved through external effects on the learner in traditionally constructed instructional settings.

However, the cognitive approach to instruction brings the learner into the centre of instruction. Learning is achieved by the learner via actively participating in the process. As cognitivism involves the building up of knowledge systems (Davis, 2003), the process by which humans acquire knowledge (cognition) includes thinking, perceiving, attending and understanding (Wilson, 2000). Therefore, contemporary cognitive theorists give high priority to the individual’s attempt and control in learning. Generally the focus in learning

is on how learners receive the stimulus, how they process and organize the received stimulus, and how they attain the retention of the things learned to be used when required in the future. Naturally, putting the learner in the centre brings about debates on learners’ learning experiences, strategy choice, attitudes, motivation and many other factors that may affect the learner’s progress or achievement.

Nevertheless, today’s curriculum studies are found to be still under the influence of the behaviorist theories. The main reason for this influence is that the behavioral approach to instruction involves defining objectives precisely, teaching in small steps, encouraging active responding, and emphasizing the importance of practice and feedback and the need to use reinforcement (Kaplan, 1990). Thus, especially in determining the objectives, and testing the teaching-learning process and evaluation behaviorism is seen to be influential in curriculum design and development (Demirel, 2002).

Concerning language teaching, various approaches, methods or techniques have been developed. In fact, limited reflections of the theories developed within the field of general education could be observed in the traditional foreign language classroom applications. Instead, a language teaching methodology, primarily based on the theories of second language acquisition has emerged. Then, the instructional features like objectives, syllabus specifications, types of activities, roles of teachers, learners, materials have been formulated, through these methods, to design a curriculum. Most of these language teaching methods have been popular especially between 1950s and 1980s, the period known as ‘The Age of Methods’ (Rodgers, 2001).

To begin with, Grammar Translation Method is nearly the oldest method of language teaching. Besides being a method for teaching Latin, with the existence of modern languages (e. g. Italian, French, English) in European school curriculums, in the eighteenth century, Grammar Translation Method survived as a primary instructional tool

in language teaching (Richards & Rodgers, 1986). Especially between 1840s and 1940s it was widely used. As the name suggests, the Grammar Translation Method has a nature that depends on grammar rules and vocabulary knowledge (Larsen-Freeman, 1986; Richards & Rodgers, 1986; Koç & Bamber, 1997; Brown, 2001; Johnson, 2001). The courses usually begin with a representation of a language rule and a list of vocabulary to be learned. Usage of the native language is not forbidden, on the contrary, it is mostly a crucial means of foreign language instruction. Then, some sentences are given as translation exercises. Grammar Translation Method is mainly criticized for focusing on the ability to ‘analyze’ language rather than the ability to use it (Schmitt & Celce-Murcia, 2002) As the courses are based on teaching grammar rules and vocabulary, in most cases, Grammar Translation classes are far from the usage of authentic uses of the language. Besides, written language but not spoken language is emphasized. However, the written language is limited to sentence level exercises; so, writing skills can be developed at the very simplistic level in Grammar Translation classes. Although it is viewed as quite an outdated method by many, it is still preferred by some teachers. No underlying theory of the Grammar Translation Method is reported in the literature.

Another significant method of language teaching has been the Direct Method. Criticisms against the Grammar Translation Method, built especially on F. Gouin’s studies, and later developed by Berlitz and some others, led to the establishment of the Direct Method (cited in Larsen-Freeman, 1986; Richards & Rodgers, 1986; Brown, 2001; Johnson, 2001). Direct Method bears the idea that a foreign language can best be taught through the use of the target language, similar to the acquisition of the first language. The usage of L1 is avoided in Direct Method classes. Everything should be introduced and explained in the target language. Thus, oral proficiency is emphasized over written language, and everyday vocabulary is taught. Accuracy is also emphasized in language

teaching. The Direct Method is implemented through the use of exercises such as reading aloud, question and answer exercise, self-correction, conversational practice, fill-in-the blank exercises, dictation, map drawing, and paragraph writing

However, application of these principles into the classrooms bears some limitations besides offering considerable solutions on the limitations of the Grammar Translation Method. The major inadequacy of the Direct Method can be explained in terms of the role of the teacher, that is, the Direct Method requires teachers to be highly proficient in the target language (Schmitt & Celce-Murcia, 2002). The teacher replaces the textbook, and becomes a crucial factor in the class. To be precise, the teacher needs either to be a native speaker or have a native-like fluency, because oral proficiency in everyday language, accuracy, and the avoidance of L1 usage is emphasized. By the same token, success in a foreign language is limited to the proficiency level of the teacher. Besides, viewing language learning from the perspective of L1 acquisition might pose another source of difficulty, because second language learning is different from L1 learning from many respects. For instance, a L1 learner has many opportunities for exposure to the target language while the second/foreign language learner may not always have opportunities for practicing the language in the target language community. In addition, the Direct Method lacks in taking possible learner differences into consideration (e.g. the abilities of a child and an adult may not be the same).

Toward the end of 1950s came The Audiolingual Method, a method derived from the principles of behaviorism (Larsen-Freeman, 1986; Richards & Rodgers, 1986; Koç & Bamber, 1997; Brown, 2000; Brown, 2001; Johnson, 2001; Richards, 2002). According to the principles of the Audioligual Method, language learning is merely habit-formation. Naturally, the teacher is the central figure to condition the learner. Mistakes should be corrected at all costs lest they could cause bad habits. Oral language is emphasized over

written language. When taught, the level of student writing is limited to the level of oral language the students have acquired. The order of language skills to be mastered in this method is listening, speaking, reading, and writing. The method aims at equipping the learners with accurate pronunciation and grammar, ability to respond quickly and accurately in speech situations, and knowledge of sufficient vocabulary to use with grammar patterns. Major teaching techniques associated with this method can be exemplified as dialog memorization, expansion drills, repetition drills, chain drills, single-slot substitution drills, multiple-single-slot substitution drills, transformation drills, question and answer drills, use of minimal pairs, dialog completion, and grammar games.

Besides offering advantages in terms of oral skills, the major limitations of Audolingual Method result from the underlying theory, behaviorism. For instance, a student who learns a language by the use of this method might learn to respond to the question ‘- How are you?’ as ‘- Fine thanks, and you?’. However, when he encounters a speaker of the target language who asks him the same question, most probably he will automatically respond in the same way, regardless of whether he is really fine or not, as he had learned in class. In fact, it is not likely to claim that real learning takes place in such a situation, because the learner seems to be far from answering the question consciously.

Meanwhile another group of language teaching attempts, as they focus more on the learner, referred to as Humanistic Approaches has taken place in the field of language teaching (Richards&Rodgers, 1986; Brown, 2001; Johnson, 2001). Silent Way, Community Language Learning, Total Physical Response, and Suggestopedia are the major humanistic language teaching approaches (Johnson, 2001). Silent Way was developed by Gattegno, and views foreign language different from L1 learning. Language learning is seen as a problem solving activity to be engaged in by the students both independently and as a group. Vocabulary is emphasized as a central dimension of

language learning. The teacher directs the class silently, and makes use of some colored rods to present the teaching points. The students are expected to deduce meanings using these visual aids. Mastering the sound system and providing the students with oral facility represent the major goals of language learning. In the later stages, the students write the sentences they create. The language skills reading, speaking, and writing are used to reinforce each other. Errors are seen as indicators of the parts that learning could not been fulfilled. Although the teacher learner relationship seems to be a traditional one, the learner is responsible for his own learning. Learner autonomy is emphasized in language learning (Larsen-Freeman, 1986). Language learning is more of a discovery or a problem solving activity while the teacher indirectly governs the class. Some of the techniques associated with the Silent Way can be counted as sound-color charts, teacher’s silence, peer correction, rods, self-correction gestures, word charts, fidel charts, and structured feedback. Community Language Learning, developed by Charles A. Curran, has been the name of another ‘humanistic approach’ to language learning (Richards&Rodgers, 1986; Brown, 2001; Johnson, 2001). This method can best be characterized by giving importance to "affective" factors in the learning process. The teacher is like a counselor who understands and supports the students in their attempts to master the target language. The students are encouraged to take responsibility of their own learning, no restriction on the usage of L1. There is no syllabus designed before the course, new topics are decided on as the teaching goes on. About the areas of language to be studied, particular grammar points, pronunciation patterns, and vocabulary are worked with. Language is primarily for communication, so understanding and speaking the language fluently is emphasized over reading and writing. Reading and writing are studied later based on what the students have learned. Tape-recording student conversation, transcription, reflection on experience,

reflective listening, small group tasks are some of the techniques applied in a typical Community Language Learning classroom.

Another ‘humanistic approach’ to language teaching has been the Total Physical Response Method (Larsen-Freeman, 1986; Richards & Rodgers, 1986; Brown, 2001; Johnson, 2001). This method emphasizes the importance of the comprehension skills, especially for the initial stages of language learning. The teacher begins with the imperative structures and the students are expected to listen and respond to the teacher’s commands. After the students begin understanding the commands, they can learn to read and write them. Grammatical structures and vocabulary are emphasized over other areas. Especially at the initial stages of language learning the students are imitators of the teachers, but later the students are involved in communication activities depending on their progress. Using commands to direct behavior, role reversal, and action sequence are some of the techniques used in Community Language Learning classes.

Georgi Lozanov’s Suggestopedia was another attempt to build a method of language teaching (Larsen-Freeman, 1986; Richards & Rodgers, 1986; Brown, 2001; Johnson, 2001). Suggestopedia was built on the idea that students bring with them some psychological barriers to learning into the classroom. Thus, increasing students’ confidence, and removing the barriers that may hinder learning have been the primary goals of Suggestopedia. The physical setting of the class is designed in a way as comfortable and relaxing as possible for the learners. Music of a relaxing tone and rhythm is provided during the lessons. The teacher is the authority figure in the class. The students learned the foreign language for daily communication. In addition, students read dialogs or write imaginative texts. Usage of L1 is not restricted, and errors are tolerated in this method. The teacher gives explanations on grammar rules, vocabulary etc. whenever the students need, but he should not bore the students. Peripheral learning, positive

suggestion, visualization, choosing a new identity, role-play, first concert, second concert, primary activation, secondary activation are some of the principal techniques used in Suggestopedia classes.

The Natural Method is another language teaching method with an emphasis on relaxing students. The Natural Approach was developed by Tracy Terrell, based on Krashen’s theory of second language acquisition (Richards & Rodgers, 1986; Brown, 2001). The Natural Method aims at developing basic personal communication skills in order to meet the needs of people in everyday situations like conversations, shopping, listening, listening to music etc. Direct use of the target language is highlighted. When doing this, students are let free about speaking until they are able to. Meanwhile, the teacher’s task is to provide students with understandable language. Thus, the teacher is a central figure and undertakes the duty to be the main source of speech, a variety of classroom activities such as commands, game, skits, and small group work.

On the other hand, Communicative Language Teaching has been a relatively contemporary approach that primarily emphasizes the communicative skills and meaning (Larsen-Freeman, 1986; Richards & Rodgers, 1986; Celce-Murcia, 1991; Brown, 2000; Brown, 2001; Johnson, 2001). It is widely used all over the world. Language is viewed merely for communication, and improving students’ communicative competence has been the primary goal of language teaching. Criticisms on the previously developed methods for being notional, but being inadequately functional and communicative had a significant role in the emergence of the Communicative Language Teaching (Johnson, 2001). That is to say, the previous methods mostly focused on providing the students with grammatically correct sentences; however, it is not likely to claim that those methods always enabled the students to know and apply where and how to use the sentences he has learned. Accordingly notional syllabuses were arranged according to the grammatical subjects (e.g.

prepositions, nouns etc.) whereas the functional syllabuses were arranged in relation to the functions (e.g. talking about yourself, meeting people etc.). Then, in order to make available the communicative purposes addition of techniques such as role play, using authentic materials, scrambled sentences, language games, picture strip story resulted in the emergence of the Communicative Language Teaching. None of the four language skills is neglected. The teacher’s role in a Communicative Language Teaching classroom is less dominant, and students are more responsible in their learning process. The teacher facilitates the communicative situations while the students are actively involved in the communicative tasks.

When these methods of language teaching are evaluated in terms of theory of language, theory of learning, objectives, syllabus, learner roles, teacher roles, language skills, activities, error handling, and materials, it is easily realized that these methods lack in meeting the needs of the language learners in many respects (see Celce-Murcia, 1991; Koç & Bamber, 1997 for more). Especially, in terms of the place of writing, comparing and contrasting these traditional methods of language teaching indicates that writing skill is either neglected, or, at least, other skills preceded writing (except for the Grammar Translation Method). As language is regarded as a means of communication among people, conveying the message orally has been primarily focused. Even if taught, writing skill most of the time has been composed of just copying or of imitating short strings of language, and was used to master certain structural patterns. In other words, oral communication has been prioritized over written communication.

A more significant deficiency of the afore-mentioned methods can be reminded as the place and contribution of learners. In other words, the value devoted to the learner is an unsatisfying point to be criticized in these methods because the syllabuses based on these methods are mostly teacher-oriented; the learner is dependent on the teacher. It is also the

case in Turkey (Bada & Okan, 2000). Although the student, the teacher, material, method and evaluation have been the commonly agreed on components of a standard classroom application (Kitao, 1997) the relationship between these components, and the value devoted to each may vary. Not surprisingly, it is possible to conclude that one component is meaningless without the other, in terms of classroom applications. However, when we evaluate the relationship between each of these components, generally the teacher adopts a method, performs the task of teaching and evaluates whether the student has learned. The student is only responsible for learning what is presented. The learner’s traits of learning are not given due attention. The differences between learners and the processes they go through when learning a language are not paid enough attention. On the other hand, the cognitive theory regards learners as mentally active and dynamic during the learning process; regardless of they are learning through their first or second language (Chamot, 1995, p. 15). Therefore, the student has become a much more important component among the others in designing learning situations from a cognitive perspective.

In view of the arguments advanced above, paying more attention to the learner brought the possible differences between the learners into discussion. In the same fashion, characteristics such as age, experience, purpose, linguistic and social background, aptitude for language learning, motivation, learning strategies, amount of exposure to the target language and even the teachers the learners have are reported as some of the aspects that second language learners differ from each other (Koç & Bamber, 1997, p. 2.2). Some of these differences (such as age, gender etc.) may be hereditary, whereas some others (level of education, motivation etc.) are acquired later, and these differences may result in some preferred learning styles and strategies of learners. Hence, the traditional views and methods of language teaching seem to lack in handling such factors which are assumed to affect the teaching-learning process.

Naturally, any curriculum designed traditionally without taking such factors into consideration, is likely to be unsuccessful or not as successful as expected, in achieving the goals of education. Hence, educational research has recently been largely directed towards the learners, more than focusing on other components of instruction. That is to say, for the last few decades, a vast majority of the research on education has been devoted to the investigation of learner characteristics, and the processes learners go through when learning something. In a sense, the term ‘learning’ replaced the previous term ‘teaching’ to indicate the focus of curriculums. Accordingly, such cognitive studies of general education brought similar perspectives to foreign language instruction.

THE NATURE OF LANGUAGE LEARNING

Having examined various approaches and methods for language learning, the nature of language learning needs to be known because none of the language teaching methods has proved to be the perfect method for language teaching. At least, it is not likely to claim that foreign language teaching methodology has reached its margins. Understanding how a language is learned can lead to more effective teaching of languages. Thus, understanding the nature of language learning can, above all, facilitate setting realistic goals for the curriculum (Spada & Lightbown, 2002). However, the nature of language learning has never been an easily identifiable subject. In this sense, perhaps, the limitations of ELT methods should be regarded as an indicator of the complexity of language learning instead of merely blaming these methods for being at fault in achieving the goals of effective language learning.

To begin with, distinguishing between teaching and learning will possibly be a useful starting point for understanding the nature of learning. Briefly, teaching can be defined as facilitating learning or increasing the capacity to learn (Joyce& Weil, 1996; Brown, 2000). Certainly, only after identifying learning, a teacher can facilitate learning. A number of, most of which are synonymous, definitions and descriptions can be found in the literature. For instance, Blair et al. (1967) define learning as any behavioral change which is a result of experience, and which causes people to face later situations in different ways. This definition of learning seems to be consistent with Bruner’s (1960) view that learning should not only be a means which takes the learner to somewhere but also help him go further. However, a contemporary understanding of learning may generate the following seven statements about learning (Brown, 2000, p. 7):

1- learning is acquisition or ‘getting’

2- learning is retention of information or skill

3- retention implies storage systems, memory, cognitive organization

4- learning involves active, conscious focus on and acting upon events outside or inside the organism

5- learning is relatively permanent but subject to forgetting

6- learning involves some form of practice, perhaps reinforced practice 7- learning is a change in behavior

What attracts the most attention in defining learning is that learning actually suggests an active role of the learner. Although learning can not be said to be defined always in the same words, the central considerations appear to be similar. For example, in addition to being cumulative outcomes of the contemporary views of learning, the definition from Brown (2000) to some extent provide more detailed definitions of learning.

Learning is in any case an activity carried out by the learner. As is also reminded by Richards (2001), although the traditional methods of teaching viewed learners as passive recipients of the teacher’s methodology, learning is today accepted as a more active process. Another dimension that can be added to learning is that learning is at the same time social (Spada & Lightbown, 2002). Thus, when the learner is involved in learning it is suggested that the individual cannot be isolated from his environment. The learner, specifically the language learner, is in an interaction with the people around him.

Concerning language learning, the literature on language teaching methodology presents a variety of studies. For instance, Ellis is reported to conduct a survey on second language acquisition research in 1994 and include 1500 references to research in this area (cited in Spada & Lightbown, 2002). Today it is not difficult to estimate that it has doubled many times. However, although the literature on language teaching has presented a large number of studies to serve language teaching methodology it appears that the needs of language learners have not been met fully in terms of mastering a language.

Not surprisingly, the literature on language teaching methodology includes various views and standpoints for explaining and facilitating language learning. A number of questions can be raised in terms of understanding language learning (e.g. ‘Is language learning a subject of linguistics?, or Is it a matter of psychological studies?, or Should language learning be explained depending on a child’s way of learning his mother tongue? etc.). In fact, it can be asserted that the field of language teaching methodology has been the stage for attempts to find out answers to such questions. To be precise, linguistic and psychological findings with the discoveries about first language acquisition have been the primary sources of effect in foreign/second language teaching methodology.

Most of the past studies on language learning are reported to have been originated from linguistic research. In other words, studies and theories that take the language as the

starting point appear to have dominated the area in the past. Consequently, it is not likely to claim that language teaching methodology (either as a second or a foreign language) could benefit sufficiently from curriculum development studies, instead linguistics and applied linguistics have been the primary sources for language instruction (Finney, 2002). Even in Prator’s terms (1991, p. 14) ‘there have been those who have argued that a Ph.D. in linguistics was the only adequate preparation for a specialist in language instruction, even if the degree was organized without reference to teaching’.

Certainly, this is not to deny the significance of linguistics and linguists to language teaching methodology but to affirm the principal role of the discipline. In this sense, it seems reasonable to simulate disciplines which deal with language teaching to the political parties in a country. Just as each political party offers projects or solutions from its own perspective, each discipline associated with language teaching offers unique explanations and solutions. Consequently, findings from linguistic studies have been the most important sources for bringing theory into practice as part of a relevant discipline Applied Linguistics, and the field of language teaching has widely been named Second Language Acquisition (Prator, 1991; Schmitt & Celce-Murcia, 2002).

Just at this point, it is worth noting that, as one of the commonly known applied linguists, Krashen’s views and suggestions have been a significant source of explaining language learning (Krashen, 1981). Firstly, Krashen sets a distinction between ‘acquisition’ and ‘learning’. Krashen proposes that there are two ways of mastering a foreign language; through ‘acquisition’ or ‘learning’. Acquisition is described as a natural and subconscious learning, just like children who learn their mother tongue. Linguistic forms are not consciously focused and errors are not corrected in acquisition. On the other hand, language learning is introduced as a conscious process where linguistic rules may be focused on in isolation, and where errors can be corrected.

Making the distinctions between acquisition and learning, Krashen (1981) hypothesizes that adults have two independent systems for developing ability in second languages –subconscious language acquisition and conscious language learning (Monitor Theory). Language acquisition is considered as more important than learning. Language learning is regarded mainly as useful for monitoring the unconsciously acquired language patterns. Thus, becoming aware of the erroneous usages of the language and correcting them are accepted as tasks of monitoring.

It is again hypothesized through Natural Order hypothesis that children acquire some grammatical patterns earlier than some others, and it is assumed that this can be applied to adults who learn a foreign or second language. For instance, ‘-ing’ forms of language are found to be mastered before ‘plural’ forms by children (p. 58), and when teaching adults a second or foreign language, children’s route for learning their first language is advised.

Accordingly, the language used by the mother when a child learns his first language has constituted another dimension of explaining the foreign or second language learning process. That is, the Input hypothesis proposes that the most important thing to do is to provide the acquirers of a language with ‘comprehensible input’ (Krashen, 1981). The level of language used when teaching a language is advised to be appropriate for the language learner’s level of language.

Another significant hypothesis formulated about language learning is Krashen’s (1981) Affective Filter hypothesis. It is proposed that learners need the right affect for receiving the input provided. That is, the feelings or emotions of the language learners are assumed to be effective on their acquisition of the language. If a language learner has negative feelings toward the language, most probably, he will be closed to receiving any

amount of language provided for him. Socio-affective, emotional, or attitudinal characteristics of the language learner are addressed through this hypothesis.

Resulting from Krashen’s distinction, a child’s learning the mother tongue is described as matter of acquisition whereas an adult’s learning a second language in the classroom is quite a conscious process, learning. Although, acquisition is found advantageous for being longer lasting than learning at the same time it takes a longer time to acquire a language (Krashen, 1981). Thus, besides other factors, due to time requirements, physical, psychological, or intellectual differences between a child and an adult establishing language learning merely on the principles of acquisition is far from being applicable. In fact, when a child acquires a language, the level of language he knows is most probably limited to speaking and hearing that language. The individual needs to receive instruction for a higher level of proficiency in the language, especially in written language.

To state briefly, second or foreign language teaching has benefited from and largely depended on first language acquisition for a long time (see Brown, 2000 for a further discussion). Linguistic habits acquired when learning the native language assumed to be effective in learning another language as well. Thus, especially with the contribution of the behavioristic view, a child’s language learning behaviors when learning his mother tongue formed the base for many studies and views on second language learning (Nunan, 2001). The emergence of the Audio-lingual Method can be given as an example for such a combination of linguistic and psychological theories. The traditional language teaching methods have come consistent with such hypotheses and in effect of psychological theories developed. To come clear with the terms, psychology studies the nature of the learner, the nature of the teaching learning process while the language itself is the subject of study in linguistics.

However, the difference between psychological theories and linguistic theories stimulated some discussions on whether language learning is different from learning in general or not. For instance, viewing language learning from a linguistic perspective might presume that language learning is related to an ‘innate knowledge of principles common to all languages’ (Spada & Lightbown, 2002) while, a psychologist can view language learning as only another instance of learning in general (Rubin, 1987).

In fact, it seems that both views have correct assumptions but it is not likely to claim that either of the views is completely true or completely false. Relevant to our topic here, Blair et al. (1967, p. 104) remind that a specific technique which works in learning a certain subject (e.g. music) may not be appropriate for learning another subject (e.g. biology), but basic principles of learning can be valid for both. To put it metaphorically, language learning and learning in general may be simulated to two different computer programs such as PDF or WORD. Certainly, these programs are distinct from each other in some respects. For instance, some changes can be made on a WORD page, but it is not possible to do the same things in the same way on a PDF page. On the other hand, there are also some similar functions and operations that can be performed on both PDF and WORD pages. Saving the page on the computer, or printing the page can be given examples of the similarities between these two programs.

The field of language teaching methodology has also been the subject of some other, most of which are interrelated disciplines. Thus, interactions of linguistics with some other fields gave birth to a number of research fields (e.g. psycholinguistics, and sociolinguistics). That is to say, as more psychologists have been interested in language learning, a shift toward psychology has been experienced (Prator, 1991). Therefore, the emergence of ‘psycholinguistics’ has been the result of such a shift toward psychology.