INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES

DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGE TEACHING

ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING PROGRAM

THE EFFECTS OF TEACHING NEGATIVE POLITENESS STRATEGIES

ON ORAL COMMUNICATION SKILLS OF PROSPECTIVE EFL

TEACHERS

M.A THESIS

By

Sibel KAHRAMAN

Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Cemal ÇAKIR

Ankara August, 2013

ii

First of all, I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Assist. Prof. Dr. Cemal ÇAKIR, for his continuous guidance and support throughout this thesis. With his valuable inspirations in Academic Discourse class in my master’s study, I was introduced with this field and carried out this research.

I am especially grateful to all my Group 101 students at Gazi University ELT Program in the Spring Semester of 2012-2013 academic year. This research achieved its objectives thanks to the enjoyable lessons with them and the motivating energy they have.

I would like to thank my dear colleagues, Res. Assist. Zeynep Çetin KÖROĞLU, Res. Assist. Nurgül ÖZCAN, Res. Assist. Tuğba Elif TOPRAK and Res. Assist. Şafak MÜJDECİ for their academic and psychological supports. I am grateful for their helpful comments and smiling faces which made writing this thesis easier. I also would like to thank Dr. Asuman AŞIK for her help and cooperation in Oral Communication Skills II class.

I would like to extend my special thanks to my lovely friends Res. Assist. Ufuk BALAMAN, Elif BALAMAN, Ebru ASAL, Dilek ARCA, Tuğçe KAYA and Volkan ÖZKURT for their endless support and patience although I could not spare enough time for them during the year. Also, I would like to thank my dear student Batuhan KARAGÖZ, who is now fighting against leukemia as it is now my turn to support him.

Lastly, my deepest thanks go to my parents and sisters for their trust and belief in me to reach all my goals in my life.

iii

NEGATİF KİBARLIK STRATEJİLERİNİN ÖĞRETİMİNİN İNGİLİZCE ÖĞRETMEN ADAYLARININ SÖZLÜ İLETİŞİM BECELERİNE OLAN ETKİLERİ

KAHRAMAN, Sibel

Yüksek Lisans Tezi, İngiliz Dili Eğitimi Anabilim Dalı Tez Danışmanı: Yar. Doç. Dr. Cemal ÇAKIR

Ağustos-2013, 138 sayfa

Bu çalışma İngilizce öğretmen adaylarının sözlü iletişim becerilerinin gelişimi için Sözlü İletişim Becerileri dersinde negatif kibarlık stratejilerinin öğretiminin etkilerini araştırmaktadır. Çalışmada deneysel araştırma desenlerinden ön-test son-test kontrol gruplu deneysel araştırma deseni kullanılmıştır. Çalışma 2012-2013 akademik yılı Bahar Döneminde gerçekleştirilmiştir ve deney sürecini tamamlamak on hafta almıştır. Araştırmanın çalışma grubunu Gazi Üniversitesi, İngiliz Dili Eğitimi Anabilim Dalı’nda okuyan birinci sınıf öğrencilerinden oluşan iki grup oluşturmaktadır. Nitel veriler, ön-test ve son-test olarak kullanılan bir söylem tamamlama testi ve deney süreci sonunda uygulanan bir yazılı görüşme formu yoluyla elde edilmiştir.

Çalışmanın ön-test ve son-test sonuçlarının analizi ve karşılaştırılması, öğretmen adaylarının deney sürecinden sonra sözlü iletişim becerilerini geliştirdiklerini göstermiştir. Yazılı görüşme formu sonuçları öğrencilerin negatif kibarlık stratejilerini öğrenmeye yönelik olumlu görüşlerini ortaya koymuştur. Ayrıca, öğrenciler bu stratejileri İngiliz Dili Eğitimi öğretim programındaki bir derste öğretilmesinin gerekliliğini vurgulamışlardır. Dolayısıyla, Sözlü İletişim Becerileri dersinde negatif kibarlık stratejilerinin öğretiminin öğretmen adaylarının sözlü iletişim becerilerini geliştirmede etkili olduğu sonucuna varılmıştır. Bulgular sonucunda, ileride yapılabilecek çalışmalar için önerilerde bulunulmuştur.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Kibarlık, negative kibarlık stratejileri, sözlü iletişim becerileri, İngiliz Dili Eğitimi.

iv

THE EFFECTS OF TEACHING NEGATIVE POLITENESS STRATEGIES ON ORAL COMMUNICATION SKILLS OF PROSPECTIVE EFL TEACHERS

KAHRAMAN, Sibel

M.A Thesis, English Language Teaching Program Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Cemal ÇAKIR

August-2013, 138 pages

This study investigates the effects of teaching negative politeness strategies in Oral Communication Skills course for the development of oral communication skills of prospective EFL teachers. The randomized pre-test post-test control group design as an experimental research design was used in this study. The study was carried out in the Spring Semester of 2012-2013 academic year and the treatment process took ten weeks to complete. The study group of the research comprises two groups of freshmen pre-service teachers at Gazi University, English Language Teaching Program. The quantitative data were gathered through a discourse completion test applied as pre and post-tests and through a written interview form conducted at the end of the treatment process.

The analysis and comparison of and post-test results indicated that the pre-service teachers improved their oral communication skills after the treatment process. The written interview form results showed that they had positive opinions towards learning negative politeness strategies. They also emphasized the necessity of teaching these strategies in one of the courses at ELT curriculum. Therefore, it was concluded that teaching negative politeness strategies in Oral Communication Skills course is effective for developing oral communication skills of prospective EFL teachers. According to the findings, suggestions are made for further studies.

Key terms: Politeness, negative politeness strategies, oral communication skills, English Language Teaching.

v

vi APPROVAL ... i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... ii ÖZET ... iii ABSTRACT ... iv DEDICATION ... v TABLE OF CONTENTS ... vi

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES ... x

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ... xi CHAPTER I ... 1

INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.0 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Statement of the Problem ... 1

1.2 Aim of the Study ... 2

1.3 Significance of the Study ... 3

1.4 Limitations of the Study ... 4

1.5 Assumptions of the Study ... 4

1.6 Definitions of the Key Concepts ... 4

CHAPTER II ... 6

REVIEW OF LITERATURE ... 6

1.0 Introduction ... 6

2.1 Face and Facework ... 6

2.2 Politeness ... 8

2.2.1 Theories on Politeness ... 9

vii

2.3 Brown and Levinson’s Politeness Theory ... 15

2.3.1 Face-threatening Acts (FTAs) ... 16

2.3.2 Strategies for Doing FTAs ... 18

2.3.2.1 Positive Politeness ... 19

2.3.2.2 Negative Politeness ... 22

2.4 Critique of Brown and Levinson’s Theory of Politeness ... 31

2.5 Studies on Brown and Levinson’s Theory of Politeness in TEFL ... 37

2.6 Conclusion ... 43

CHAPTER III ... 44

METHODOLOGY ... 44

3.0 Introduction ... 44

3.1 Research Design ... 44

3.2 Study Group of the Research ... 44

3.3 Data Collection Procedure ... 44

3.4 Data Collection Instruments ... 46

3.4.1 Discourse Completion Test (DCT) ... 47

3.4.2 The Written Interview Form ... 50

3.5 Data Analysis ... 50

3.6 Data Collection Process ... 51

3.6.1 Weekly Treatment ... 51

3.7 Conclusion ... 56

CHAPTER IV ... 57

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ... 57

4.0 Introduction ... 57

4.1 Results and Discussion Related to the First Research Question ... 57

viii

4.1.3 Analysis of the Pre-test Answers of the Experimental Group ... 67

4.1.4 Discussion of the Pre-test Answers of the Experimental Group ... 74

4.2 Results and Discussion Related to the Second Research Question ... 76

4.2.1 Analysis of the Post-test answers of the Experimental Group ... 76

4.2.2 Discussion of the Post-test answers of the Experimental Group ... 87

4.3 Results and Discussion Related to the Third Research Question ... 88

4.3.1 Analysis of the Post-test Answers of the Control Group ... 89

4.3.2 Discussion of the Post-Test Results of Control and Experimental Groups ... 96

4.4 Findings and Discussion Related to the Fourth Research Question ... 97

4.4.1 Oral Communication Skills ... 98

4.4.2 ELT Curriculum ... 99

4.4.3 Course Content ... 101

4.5 General Discussion ... 102

4.6 Conclusion ... 103

CHAPTER V ... 104

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS ... 104

5.0 Introduction ... 104

5.1 Summary of the Study ... 104

5.2 Pedagogical Implications ... 107

5.3 Recommendations for Further Research ... 108

REFERENCES ... 109

APPENDICES ... 123

Appendix I DCT………...………...……….….124

Appendix II Written Interview Form ………... 127

Appendix III First Week's Worksheet ………..128

ix

Appendix VI Fourth Week’s Worksheet ………... 131

Appendix VII Fifth Week’s Worksheet ………132

Appendix VIII Sixth Week’s Worksheet ………..133

Appendix IX Seventh Week’s Worksheet ………134

Appendix X Eighth Week’s Worksheet ………...135

Appendix XI Ninth Week’s Worksheet ……….………...136

Appendix XII Tenth Week’s Worksheet ………..137

x

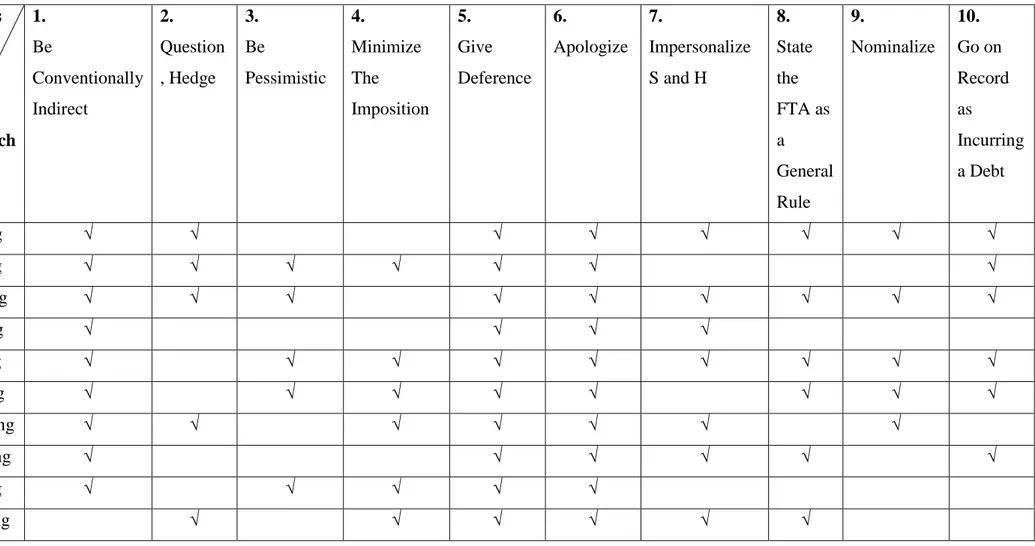

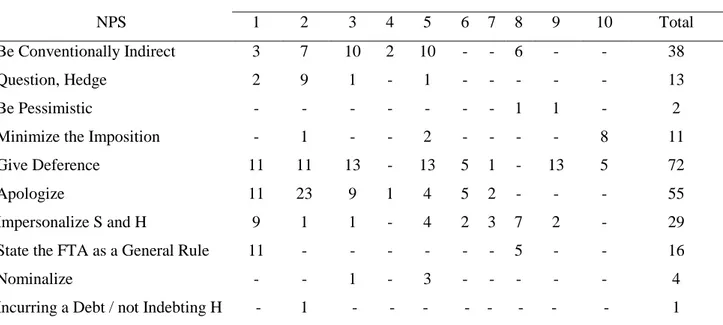

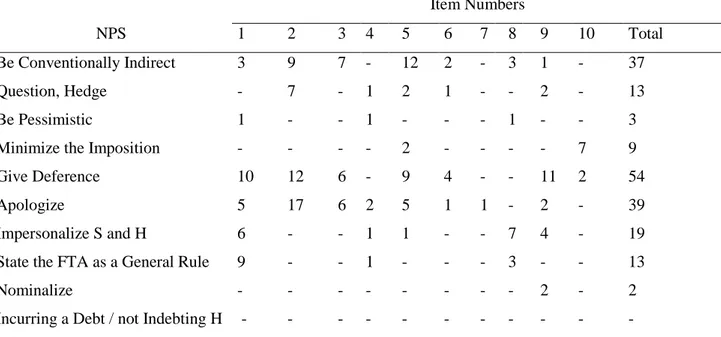

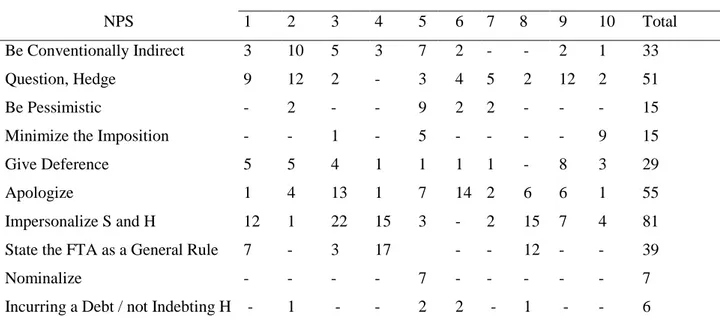

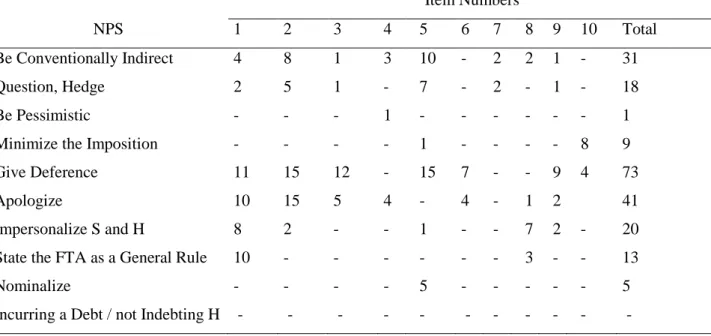

Table 1. The Appropriateness of the Strategies for the Speech Acts ... 48 Table 2. Frequencies of NPS for each DCT Item in the Pre-test of the Control Group ... 58 Table 3. Frequencies of NPS for each DCT Item in the Pre-test of the Experimental

Group ... 68 Table 4. Frequencies of NPS for each DCT Item in the Post-test of the Experimental

Group ... 77 Table 5. Frequencies of NPS for each DCT Item in the Post-test of the Control Group ... 89 Figure 1. Possible strategies for doing FTAs ... 18

xi

EFL: English as a Foreign Language

ELT: English Language Teaching

NPS: Negative Politeness Strategies

DCT: Discourse Completion Test

FTAs: Face-Threatening Acts

TEFL: Teaching English as a Foreign Language

S: Speaker

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

1.0 Introduction

In this part, the problem which led to this study is stated and the aim of the research is identified. In order to indicate the vitality of the research in this field, the significance of the study is represented in detail. As there are some assumptions and limitations in the research, they are also included in this part of the research. Lastly, some definitions of key terms are presented.

1.1 Statement of the Problem

In 1978, Brown and Levinson published their politeness theory claiming it to be universal for all the languages, cultures and human beings. Since that time, many studies have been carried out to determine both the validity and limitations of this theory. It has been an area of interest especially for social scientists working in sociolinguistics, sociology, anthropology and social psychology. As lying in the heart of effective oral communication, politeness is studied in many areas of social sciences where human interaction is focused on. Relevant to this issue, Watts et al. (1992) claim that linguistic politeness is crucially a social phenomenon and, if understood properly, it might constitute an important key to the understanding of a number of sociolinguistic problems. In order to understand these sociolinguistic problems, many cross-cultural studies have been done on speech acts such as requests, disagreements, apologies, invitations, etc. (Blum-Kulka et al., 1989; Takahashi & Beebe, 1993). The studies have shown that there are intercultural communication problems or pragmatic failure in learning a foreign language because of the variations in the use of semantic and syntactic structures as well as politeness markers. Therefore, it can be said that politeness is an important component to be able to create pragmatic awareness and competence, which are crucial for effective oral communication skills of people learning a foreign/second language.

Theories on politeness (Goffman, 1967; Leech, 1983; Brown & Levinson, 1987) attempt to explain how people establish, maintain or support social relationships by using socio-culturally appropriate communication strategies. As stated before, politeness theory is a crucial concept for people’s communicative and pragmatic competences. At this point, the conditions of the people learning English as a foreign language (EFL) needs to be considered since they need effective communication skills. By taking this into consideration, we aim to analyze the effects of teaching politeness strategies on oral communication skills of prospective EFL teachers. The reason why prospective EFL teachers are chosen is that they are the people who teach English as a foreign language in Turkey, and who need to have effective communication skills themselves firstly. The question, then, is whether the students of ELT Programs are aware of these strategies and can use them effectively in the classrooms for communicative purposes.

In this research, we hope to see fruitful results of teaching Brown and Levinson’s politeness strategies in the course of Oral Communication Skills, which takes place at the 1st year of the English Language Teaching (ELT) Program. Because a particular syllabus is not specified for this course, we also aim to contribute to the course syllabus and consequently to the ELT Program. The students will be taught negative politeness strategies (NPS) proposed by Brown and Levinson (1987) in order to improve their oral communication skills and pragmatic awareness.

1.2 Aim of the Study

Politeness theory of Brown and Levinson permeates every stage of interaction in professional and institutional communication (Pan, 2010). Therefore, it can be said this theory is a tool to teach, explain and understand social interaction and to provide an insight into what constitutes appropriate linguistic behavior in different societies and cultures. By taking this assumption into consideration, we attempt to find out the effects of teaching NPS on oral communication skills of prospective EFL teachers at Gazi University, Turkey. Hence, it differs from the other studies as it tries to find out whether these strategies in politeness theory have any benefits for the communication skills and

teaching experiences of these prospective English teachers at ELT programs. Also, it tries to contribute to the syllabus of a course at ELT curriculum.

The research questions are as follows:

What is the current status of Gazi University ELT freshmen students in terms of negative politeness strategies?

Does teaching negative politeness strategies contribute to the oral communication skills of these students?

Does teaching negative politeness strategies cause any differences between the oral communication skills of the students who are taught these strategies and those who are not?

How do the students reflect on learning negative politeness strategies?

1.3 Significance of the Study

As stated before, there have been so many critiques over Politeness Theory of Brown and Levinson and its universality. Yet, when it comes to the communication skills, this study is likely to be the first one analyzing the ability to use NPS of prospective EFL teachers at Gazi University, who are on the threshold of being EFL teachers. As they are the ones who will teach English and the classroom atmosphere is an important consideration for learning things, it is essential for these teachers to have effective oral communication skills while teaching English as a foreign language.

The findings of the study try to reveal whether Brown and Levinson’s theory of politeness and their strategies have any role in providing prospective EFL teachers with effective oral communication skills. Also, it aims at integrating politeness strategies into the course of Oral Communication Skills, which means these strategies will help develop the linguistic behaviors of prospective EFL teachers. Therefore, it can be said that this study tries to bring a new perspective as it approaches to theory in terms of the benefits it can give the students at ELT programs.

1.4 Limitations of the Study

The following limitations can be enumerated, regarding the procedures and conditions of data collection and analysis:

We studied on only NPS, positive politeness strategies and off-record politeness strategies are not included in the study.

The techniques that we use to teach NPS may be a limitation as other techniques can be used to teach them.

This study is carried out with the 1st grade ELT students at Gazi University in Turkey, so the number of the students may be a limitation.

Some difficulties may be encountered on the course of measuring as the attitudes of people can be subjective.

Students may not give answers to questions they are asked.

1.5 Assumptions of the Study

The following assumptions are taken into consideration in this research:

The participants are willing to fill in the discourse completion test (DCT).

The participants will give the exact answers to the questions.

The participants are in the same status as they are all 1st grade students at ELT Program, Gazi University.

1.6 Definitions of the Key Concepts

Face: “The public self-image that every member wants to claim for himself.” (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 61).

Face-threatening acts (FTAs): “Certain illocutionary acts are liable to damage or threaten another person’s face; such acts are known as ‘face-threatening acts’.” (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 60).

Negative face: “The want of every ‘competent adult member’ that has his actions to be unimpeded by others.” (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 62)

Positive face: “The want of every member that his wants be desirable to at least some others.” (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 62)

Positive politeness: “It is oriented toward the positive face of the hearer, the positive self-image that he claims for himself. Positive politeness is approach-based; it anoints the face of the addressee by indicating that in some respects, speaker wants hearer’s wants.” (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 70).

Negative politeness: “It is oriented toward partially satisfying (redressing) the hearer’s negative face, his basic want to maintain claims of territory and self-determination.” (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 70).

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

2.0 Introduction

In this chapter, it is aimed to represent the main concepts, issues and discussions related to the politeness concept. It starts with Goffman’s (1967) theory of facework by giving broad definitions of the terms in the theory. Then, politeness is defined by taking into consideration different points of view on politeness. After these definitions, Fraser’s four views of politeness are given briefly and Brown and Levinson’s (1987) theory of politeness is presented as the last of these views. This theory is reviewed in detail by providing information about the concepts of FTAs, positive politeness and negative politeness. Lastly, critiques of Brown and Levinson’s theory of politeness and studies on this theory in teaching English as a foreign language (TEFL) are presented.

2.1 Face and Facework

In recent years, ‘face’ and ‘facework’ have been among the most heavily debated concepts in pragmatics and sociolinguistic research. Many different kinds of theoretical models regarding these concepts have been proposed and many cross-cultural studies have highlighted the variations in specific languages and cultures. When the historical background of these notions is studied, it is clear that it was Goffman (1955) who introduced the terms first. Goffman (1955) defines the term ‘face’ as “the positive social value a person effectively claims for himself by the lines others assume he has taken during a particular contact” (p. 213). In other words, the conception of self that a person claims for himself/herself during a particular interaction is called face. When a person interacts with another, both parties present a constructed self in that encounter and seeks confirmation for that self (Cupach & Metts, 1994). All the

individuals have faces and while interacting with others, they want these faces to be approved by their interlocutors. In social scientific terms, face is described as “socially situated identities people claim to attribute to others” (Tracy, 1990, p. 210). If these conceptualizations of face are approved, we need to accept that each individual has his/her own social face adopted for the purposes of communicative interaction. That means people can have different faces on different occasions of verbal interaction and behave according to their face needs.

Goffman collected some essays on face-to-face behavior in his book ‘Interaction Ritual’ (1967). The first of these essays, ‘On Face-work’, is referred to as the source of Brown and Levinson’s notion of ‘face’ in their literature of politeness. In this book, he cites the sources for both the Chinese and American Indian concept of face, indicating the influences on his own ideas. He was mostly influenced by the French sociologist Emile Durkheim’s work called ‘The Elementary Forms of Religious Life’ (1915). Goffman’s ritual analysis of social life, for which he is directly indebted to Durkheim, is predominant in the first four essays collected in Interaction Ritual (Branaman, 1997). In his work, Durkheim (1915) states that his purpose is to explore some of the senses in which the person in our urban secular world is allotted a kind of sacredness that is displayed and confirmed by symbolic acts. That is to say, Goffman focuses on the human interaction, and what is said and done by the individuals in the social interaction. He implies that our knowledge of the world and the place we occupy in that world are gained through social interaction. It is absolutely the human interaction in which he sees forms of ritual behavior being enacted. In his first article in the book ‘On Face-work’, he makes the following point:

In any society, whenever the physical possibility of spoken interaction arises, it seems that a system of practices, conventions and procedural rules comes into play which functions as a means of guiding or organizing the flow of messages. An understanding will prevail as to when and where it will be permissible to initiate talk, among whom, and by means of what topics of conversation (1967, pp. 33-34).

By facework Goffman means to designate the actions taken by a person to make whatever he is doing consistent with face (Goffman, 1967). According to him, “facework serves to counteract ‘incidents’; that is, events whose effective symbolic implications threaten face” (1967, p. 12). Goffman suggests that such actions of facework may be conscious or unconscious, and often become habitual. Each society and culture seems to have its own facework. There are two possible practices of face-work: defensive practices and protective practices. In defensive practices people try to save their own faces and in protective practices they orient toward saving the others’ faces. People may primarily practice defensive ones or primarily protective ones, while one may expect these two practices to be taken at the same time. The avoidance process and the corrective process are two basic kinds of face-work. In the former process, the best way for a person to prevent threats to his/her face is to avoid contacts in which these threats are likely to occur. Goffman points out that “an illustration of that kind of avoidance is found in the middle and upper-class black people who avoid certain face-to-face contacts with white people in order to protect the self-evaluation projected by his clothes and manner” (1967, p. 15). When the participants in an encounter fail to prevent the occurrence of an event incompatible with the judgments of the society, then there occurs the corrective process. There are some phases in the corrective process called as challenging, offering, accepting and thanking all of which provide a model for inter-personal ritual behavior.

2.2 Politeness

Goffman’s model of facework has led other scholars into building many new conceptualizations of facework, some of whom, inspired by the work of Goffman, have studied making requests (Baxter, 1984; Brown & Levinson, 1987; Craig, Tracy & Spisak, 1986), dealing with disagreements (Goldsmith, 1992), and perceptions of forms of address (Braun, 1988). Many of the models have been designated to understand cross-cultural communication. One of these theoretical approaches based on facework theory is the study of “politeness”. The concept of “politeness” refers to the redressive action people engage in to promote face or mitigate threats to the face. Politeness includes the ways in which we treat other people in courtesy and good manners (Brown & Levinson, 1987). Different scholars have identified the term “polite” in different ways. According to Leech (1983), being polite involves making our interlocutor feel

good. So, “polite” means “friendly”. To Brown & Levinson (1987), it means making him/her not feel bad as mentioned above. Then ‘polite’ can be defined as diplomatic. And lastly, for Fraser “polite” is the “expected state”, “polite” as socially correct.

The main target in politeness is to ease the social interaction by providing a ritualistic form of verbal interaction. It is used to smoothen the stark effects of some speech acts such as disagreeing, warning, and forbidding in the course of communication. People use politeness not to show their embarrassment, anger or fear for situations in which that would not be to their advantage to show these emotions as a reflection. It is a way of inviting intimacy or of increasing the formality and social distance between people by respectfully and courteously resisting advances by another person to become more personal and friendly (Spiers, 1994).

2.2.1 Theories on Politeness

There is little agreement among researchers in the field about what exactly constitutes politeness and the domain of the related research. So there have been many different approaches towards politeness. Fraser (1990) stated four main ways of viewing politeness in the research literature: the “social-norm” view, the “conversational-maxim” view, the “conversational-contract” view and the “face-saving” view. Eelen (2001) also suggests these views, but he uses some different kinds of notions while comparing them. In addition, he includes some other theoretical perspectives in his classification of politeness research. However, Fraser (1990) thinks that research, over the years, lacks consistency among researchers on what politeness exactly is and how it may be accounted for. So, he proposed four views on politeness by examining each theory in detail. Each of these views is introduced and explained below.

2.2.1.1 Social-Norm View

According to Fraser (1990), “the social-norm view of politeness assumes that each society has a particular set of social norms consisting of more or less explicit rules that prescribe a certain behavior, a state of affairs, or a way of thinking in a context” (p. 220). When an action is approved in the society, it is assumed as a positive evaluation,

or in other words “politeness”. When an action is contrary to the values and norms of the society, this time a negative evaluation occurs, which is also called “impoliteness”. So, it can be said that this view considers politeness to be associated with speech style, in which a higher degree of formality implies a greater politeness. However, there are more criticisms on this view other than the other theories on politeness. The extreme view asserts that the interpretation of politeness as the desire to be pleasant to others in the society “has no place in the pragmatics” (Thomas, 1995, p. 150). As Fraser shares the same ideas with this view, he states that this view has few adherents in the current research on politeness. On the other hand, there seems to be a corresponding view to social-norm view, called ‘discernment politeness’, which has been proposed as the underlying basis of politeness systems in Non-Western cultures (Hill et al., 1986; Ide, 1989). The social-norm view assumes social standards similar to discernment politeness in that it refers the use of the standard in a social setting (Watts et al., 1992). Also, Ide (1989) was one of the first to express this view in her study of politeness in the Japanese society. All in all, it can be said that this approach has its own place in pragmatic research.

2.2.1.2 The Conversational-Maxim View

The conversational-maxim view roots in the work of Grice (1975). Grice argued that conversationalists are rational individuals who are, all other things being equal, primarily interested in the efficient conveying of messages (Fraser, 1990). With this object in his mind, he proposed a new perspective called Cooperative Principle. In this principle, a person should say what he/she has to say at the right time, amount and manner. Grice (1975) argues that people should make their conversational contribution when it is required, at the stage which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange. Because he believes that all the people are essentially cooperative in order to achieve the purpose of being “maximally efficient” in interaction with others. To provide this efficiency, he proposed four maxims: quantity, quality, relation and manner. An ideal conversation should have all the maxims and any violation of these maxims causes the failure of conversational failure. The maxims are below:

1. Quantity maxim: Give the right amount of information, neither too much nor too little information.

2. Quality maxim: Tell the truth.

3. Relation: Be relevant what you have said before.

4. Manner: Be clear and brief to avoid ambiguity and obscurity.

Lakoff (1973) was one of the first who based his framework on Grice’s Cooperative Principle. However, he argued that it is necessary for a conversation to have both Politeness Principle and Cooperative Principle. He extends the notion of grammatical rule and well-formedness to pragmatics. He (1973) states that “we should like to have some kind of pragmatic rules, dictating whether an utterance is pragmatically well-formed or not, and the extent to which it deviates if it does” (p. 296). So, by applying this expression to politeness issue, he considers some specific structures for sentences to be polite or not. In his later studies, he describes politeness as “a device used in order to reduce friction in personal interaction” (Lakoff, 1979, p. 64). According to him, there are two rules for Pragmatic Competence:

1. Be clear. (Grice’s maxim) 2. Be polite.

These two maxims may seem to be in conflict with each other or reinforcing at times. He also added three more rules or in other words sub-maxims to his principle:

1. Rule 1: Don’t Impose (used when Formal/Impersonal Politeness is required).

2. Rule 2: Give Options (used when Impersonal Politeness is required). 3. Rule 3: Make ‘A’ Feel Good (used when Intimate Politeness is required).

These rules may change according to situations, speakers (Ss) and hearers (Hs). If the S thinks that the situation he/she is in requires Intimate Politeness, he/she can just say “Come here”.

Despite its significance, Lakoff’s model got some criticism as it has been found too vague to be operative and it does not actually give an answer to the question of politeness issue. Van de Walle (1993), Fraser (1990) and Watts et al. (1992) have criticized Lakoff’s model as it falls short of explaining the rules in the theory and deciding on a particular strategy. As a result of these deficiencies, the model resulted in inadequate “explanatory power” (Van de Walle, 1993, p. 53).

As a reaction to the shortcomings of Grice’s and Lakoff’s models, Leech (1983) formed his own framework of Politeness Principle. As Lakoff did her studies, Leech’s studies also originated from Grice’s Cooperative Principle. They all agree that there exist some maxims and sub-maxims that guide the conversation of rational people. In Leech’s theory, there is a significant distinction between a S’s illocutionary goals and social goals. Illocutionary goals are the speech acts that a S wants to convey by his utterances and social goals describe the position the S takes on being truthful, polite, ironic and the like. By taking these goals into consideration, he proposes two conversational (rhetorical) principles – Interpersonal Rhetoric and Textual Rhetoric. As in other models, politeness is not explicitly defined, but it is involved in the domain of Interpersonal Rhetoric. This domain heavily focuses on the S’s social goals rather than his/her illocutionary goals and contains these first-order principles: those belonging to Grice’s Cooperative Principle, those associated with the Politeness Principle, those associated with an Interest Principle, and Pollyanna Principle. Interest Principle recommends the S to say the unpredictable and interesting things to his/her interlocutors. Pollyanna Principle presumes that the participants in a conversation prefer the pleasant topics to unpleasant ones. Leech’s politeness can be defined as minimizing the beliefs which are unfavorable to the hearer and thus maximizing the favorable beliefs, all the other things being equal. From this point of view, she proposes six Interpersonal Maxims (1983):

1. Tact Maxim: Minimize hearer costs: maximize hearer benefits.

2. Generosity Maxim: Minimize your own benefit; maximize your hearer’s benefit.

3. Approbation Maxim: Minimize hearer dispraise; maximize hearer praise.

4. Modesty Maxim: Minimize self-praise; maximize self-dispraise.

5. Agreement Maxim: Minimize disagreement between yourself and others; maximize agreement between yourself and others.

6. Sympathy Maxim: Minimize antipathy between yourself and others; maximize sympathy between yourself and the others.

Despite all these principles and elaborations, Leech’s framework has been criticized as “it gets lost in detail and fails to portray general picture” (Van de Walle, 1993, p. 57). The framework has been found too theoretical, rigid and away from linguistic reality to be able to explain actual language usage (Van De Walle, 1993; Watts et al., 1992). Van De Walle (1993) states that “politeness is a social phenomenon and hard to fit into the tight schemes which Leech sets up to deal with every single regular pattern that crosses his path” (p. 57).

Lakoff’s (1973) and Leech’s (1983) frameworks of politeness represent probably the most suitable approaches for cross-cultural comparisons owing to their explanatory power in the realm of cross-cultural differences in the perception and use of politeness strategies (O’Driscoll, 1996; Thomas, 1995). A number of studies have already been carried out under the general principles and maxims of these models by indicating the importance of these principles in cross-linguistic investigations (Gu, 1990; Matsumoto, 1988).

2.2.1.3 The Conversational-Contract View

This approach was first proposed by Fraser and Nolen (1981) and later elaborated by Fraser (1990). It adopts the Grice’s notion of Cooperative Principle and also recognizes the Goffman’s (1967) notion of face. Nevertheless, it differs in certain ways from the other approaches of politeness.

In this view, each person brings into a conversation an understanding of some initial set of rights and obligations which will determine what the participants can expect from the other or others (Pikor-Niedzialek, 2005). There is always possibility for renegotiation of the conversational contract because of time or change in the context. That is to say, each participant may readjust his/her right and obligations towards the other. As such, Fraser (1990) defines politeness as “the act of operating within the then-current terms and conditions of conversational contract” (p. 233), which requires the participants to assess the contextual factors constantly. So it can be said that politeness is virtually using the appropriate language for a conversation. The rights and obligations held by participants are usually determined according to cultures and conventions. For example, participants are expected to take turns in the course of conversation, to use a comprehensible language towards the others, and to speak loudly enough and seriously.

Fraser’s view of politeness has been adopted by many others. Sperber’s (1995) Relevance Theory is one of these based on the views on politeness proposed by Fraser. As politeness is described in terms of Relevance theory, it can be said that participants in a conversation enter a linguistic exchange with permissible assumptions in their minds. According to Watts’ (1992) notion of politic behavior, politeness involves maintaining the equilibrium in a relationship. Tracy (1990) is also another scholar stating that a person’s selection of politeness strategies is based on ‘rights and obligations’.

This view has received both negative and positive criticism. Its strength roots in its universal applicability and the notion of communicative contract as a dynamic concept. However, it does not elaborate enough to adequately address the concept of “politeness”.

2.2.1.4 Face-Saving View

The last view to politeness is the one proposed by Brown and Levinson (1978, 1987) and termed as the face-saving view. It is perhaps the most influential and current view to the notion of politeness. As my study is based on the strategies on their theory,

Politeness Theory of Brown and Levinson is involved under a separate heading in detail.

2.3 Brown and Levinson’s Politeness Theory

According to their observations across cultures, Brown and Levinson have concluded that there is a problem between what people are saying in verbal exchanges (e.g. apologizing, requesting, warning, suggesting) and what they claim to be saying. For instance, people rarely say things like “I hereby request …” or “Look, I’m terribly sorry to bother you, would it be awfully inconvenient if …” (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 57). However, the manner in a verbal exchange is generally evident and pure. In order to solve this difference between the manner and utterances, there are some suggested solutions. For example, when there is in-group membership and social similarity, people use small requests. On the other hand, when making a bigger request, people tend to use the language of formal politeness (Brown and Levinson, 1987). Based upon this problem, they ask what sort of assumptions and what sort of reasoning are utilized by participants to produce such universal strategies of verbal interaction. They aim at creating a formal model by taking into consideration the cross-cultural similarities and culturally specific usages. At that point, they construct a Model Person endowed with two special properties: rationality and face. By “rationality”, they mean the ability of reasoning from ends to the means. “Face”, means the want to be unimpeded and to be approved of by others in certain aspects. By creating this Model Person, they try to provide a reference model for the descriptions of verbal interaction styles in all the cultures. They attempt to characterize the “ethos” of a culture and the affective quality of social relationships. In an attempt to clarify the word “ethos”, it can be said that it is the system of values and beliefs in a society.

In order to be able to create a reference model and to support their assumptions, Brown and Levinson collected first-hand tape-recorded data from unrelated cultures and languages. English (from both sides of Atlantic), Tzeltal (a Mayan language spoken in the community of Tenejapa in Chiapas, Mexico) and South Indian Tamil (a village in the Coimbatore District of Tamilnadu).

As mentioned above, a Model Person as a competent adult member of a society has two certain properties: face and rational capacities. The notion of “face” is derived from the work of Goffman (1967) and an English folk term “losing face”, which means being embarrassed or humiliated. Face is defined as the public self-image that every member wants to claim for himself. Brown and Levinson (1987) describe face as “something that is emotionally invested, and that can be lost, maintained, or enhanced, and must be constantly attended to in interaction” (p. 61). If a member of the society maintains the face of the other, it is supposed that this other person will maintain his/her face, too. On the contrary, in case of a threat to your face, you are expected to defend your face by threatening your interlocutor. Brown and Levinson assume that the content of face may differentiate among cultures, yet the mutual knowledge of members’ public self-image or face and the social necessity to orient oneself to it in interaction are universal. Brown and Levinson claim that a Model Person has two faces: negative face and positive face. Negative face is the want of every ‘competent adult member’ that his/her actions be unimpeded by others. It gives the freedom of action and freedom from imposition to the members in a society. It is familiar with the notion of formal politeness. On the other hand, positive face is the want of every member that his/her wants be desirable to at least some others. It is the desire to be ratified, understood, approved of, liked or admired by the interactants.

2.3.1 Face-Threatening Acts (FTAs)

Certain kinds of acts intrinsically threaten the face or face wants of the addressee and/or the S. These acts are called ‘FTAs’. The acts can be done by a verbal or non-verbal communication, that is to say, more than one speech acts can be assigned to each utterance. The acts that threaten the negative face do not avoid impeding the H’s freedom of action. These acts include orders, requests, suggestions, remindings, threats, warnings, dares, promises, expressions of envy or admiration etc. The acts that threaten the positive-face want of the members do not care about their feelings and wants. Expressions of disapproval, criticism, complaints, reprimands, accusations, insults, disagreements, challenges, and expressions of violent emotions are some of these acts. FTAs are also distinguished as the ones that threaten the H’s face and the ones that threaten the S’s face. The acts that threaten the S are expressing thanks, excuses, acceptance of offers, responses to the hearer’s faux pas, unwilling promises and offers.

The other acts that directly damage the S’s face are apologies, acceptance of a compliment, break-down of physical control over body, self-humiliation, confessions and emotion leakage.

In order to assess the seriousness of FTAs, following factors are involved in many and, perhaps, all cultures:

Social distance of S and H

Relative power of S and H

Absolute ranking of impositions in the particular culture

Social distance refers to the relationship between S and H. If there is an intimate relationship between the interlocutors, then they will have a low degree of social distance. If they are strangers to each other, then this relationship is expected to have a high degree of social distance. The higher the degree of social distance, the more formal language is used between the interlocutors. Secondly, relative power refers to the power relationship between S and H. There are three types of power relationships among people. In the first one, there is an equal power between S and H. That means S may be speaking with one of his/her friends or colleagues. The other two types of power relationship occur when S has more (e.g., as a boss or instructor) or less (e.g., as an employee or student) power than H. If the other person in the conversation has more power than an individual, it is expected to use more formal and indirect language. The last factor, absolute ranking refers to the importance or degree of difficulty in the situation. For example, while doing a request, if you are asking a big favor, a large rank of imposition will occur. On the other hand, a small rank of imposition will exist when the request is small. High ranks of impositions require formal and polite languages. All these three factors interact and relate differently to the politeness of a communicative act. They carry different weights in different varieties and cultures. In order to have pragmatic competence, it is important to learn which social factors are most applicable and important to the context in which interlocutors interact.

2.3.2 Strategies for doing FTAs

If there happens a threat to the face, any S or the H tries to avoid these face-threatening acts by applying some certain strategies. These strategies are schematized exhaustively by Brown and Levinson as in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Possible strategies for doing FTAs (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 69)

If an actor goes on record in doing an act, that means it is clear for the participants what communicative intention the actor has in mind. That is to say, there is only one unambiguously attributable intention with which witnesses would concur. For example, if a person says “I promise to pick you up tomorrow.” and if the participants in the conversation concur that, then this person goes “on record” by promising to do so because this person unambiguously expresses the intention of committing himself or herself to do that action tomorrow. When a S goes on record, the main reason of his/her utterance is that he/she wants to do the FTA with maximum efficiency rather than satisfying H’s face. Brown and Levinson (1987) state that as there are different kinds of bald-on-record usage in different circumstances, “S can have different motives for his want to do the FTA with maximum efficiency” (p. 95). Direct imperatives are clear examples of bald-on-record usage.

On the other hand, if an act goes off record, there is more than one unambiguously attributable intention. For this reason, the actor may not commit himself or himself to one particular intention. Metaphor and irony, rhetorical questions, understatement, tautologies, all kinds of hints as to what a S wants or means to communicate are all linguistic realizations of off-record strategies. The actor does the action without so directly and the meaning is to some degree negotiable.

“Doing an act baldly”, without redressive action, involves doing it in the most direct, clear, unambiguous and concise way possible (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 69). For example, while requesting something, imperatives can be used by the actors. If the circumstances do not require the great sacrifices of the actors or the actor is vastly superior in power to the Hs, this strategy can be used because in these circumstances, the actors do not refrain from destroying the Hs’ faces.

While doing a redressive action, an actor gives face to the Hs. He/she refrains from the potential face damage of FTAs and does these FTAs in a way not to destroy the Hs’ faces or with such modifications or additions since in redressive action, the actor does not intend or desire any face threat and also he/she recognizes the H’s face wants. There are two forms of redressive action depending on which aspect of face is being stressed: positive politeness and negative politeness.

2.3.2.1 Positive Politeness

Positive politeness is oriented towards the positive face of the H and the positive image that he/she claims for himself. As Brown and Levinson (1987) explains:

Linguistic forms of positive politeness are in many respects representative of the normal linguistic behavior between intimate people, where interest and approval of each other’s personality, presuppositions indicating shared wants and shared knowledge, implicit claims to reciprocity of obligations or to reflexivity of wants are routinely exchanged (p.101).

What makes positive politeness different from everyday intimate language is an element of exaggeration since the S aims at satisfying the positive face of the hearers by

using the expressions of exaggeration. Positive politeness utterances are used to show the intimacy between interlocutors to imply common ground or shared knowledge. They are used as a kind of social accelerator by indicating that the speaker wants to come closer to the hearer.

The strategies of positive politeness can be categorized in three broad mechanisms, listed below. Examples are given for each strategy and the expressions in the utterances that present the strategy mentioned are given in bold. The sample sentences are adapted from Brown and Levinson (1987) and modified by the researcher.

A. Claim “common ground”: In this type S and H belong to the same group of people sharing the specific values, goals and wants.

a. Convey “X is admirable, interesting”: H’s wants are admirable or interesting for S.

Strategy 1- Notice, attend to H (his interests, wants, needs, goals): In this strategy S needs to be careful about H’s noticeable changes, remarkable possessions or anything that H wants to be approved of:

- Goodness, your hair looks perfect. You have just cut it, I think. By the way, can I borrow your car for the weekend?

Strategy 2- Exaggerate (interest, approval, and sympathy with H): Expressions of exaggeration such as intensifying modifiers or prosodics are used with intonation and stress in this strategy:

- How fabulous you look today!

Strategy 3- Intensify interest to H: S pulls H into the middle of the events being discussed by getting the attention of H:

- I opened the door, and what do you think I see? All my friends were there to celebrate my birthday.

b. Claim in-group membership with H: S and H belong to the same group sharing the same wants.

Strategy 4- Use in-group identity markers: Address forms, in-group language or dialect, jargon or slang, contraction or ellipsis are used in this strategy:

- Would you help me, babe?

c. Claim common point of view, opinions, attitudes, knowledge, empathy

Strategy 5- Seek agreement: Using safe topics and repetition are common in this strategy:

- I broke my leg. - You broke your leg!

Strategy 6- Avoid disagreement: Here token agreement, pseudo-agreement, white lies and hedging opinions are used:

- I sort of wonder …

Strategy 7- Presuppose/raise/assert common ground: Gossips, small talks, point-of-view operations, presupposition manipulations are the sub-strategies in this strategy:

- Don’t you think this is wonderful?

Strategy 8- Joke: Since jokes are based on mutual shared background knowledge and values, they are used to stress this shared values.

B. Convey that S and H are cooperators: In this second major strategy of positive-politeness, S and H are involved in the relevant activity.

a. Indicate S knows H’s wants and is taking them into account

Strategy 9- Assert or presuppose S’s knowledge of and concern for H’s wants: Negative questions may be used in this strategy:

b. Claim reflexivity (If H wants then S wants, if S wants then H wants)

Strategy 10- Offer, promise: They are used in order to show the good intention of S in satisfying H’s positive-face wants:

- I promise to pick you up tonight.

Strategy 11- Be optimistic: Presumptuous or optimistic expressions are used here:

- I’m sure, you won’t mind if I borrow your car.

Strategy 12- Include both S and H in the activity: Using ‘we’ as the subject is a strategy here:

- Give us some time to finish this.

Strategy 13- Give or ask for reasons: This strategy is a way of assuming cooperation:

- Why don’t we do something together?

c. Claim reciprocity

Strategy 14- Assume or assert reciprocity: FTA can be softened by negating the debt between S and H.

- I cooked yesterday for you, so you can cook for me today.

C. Fulfill H’s want

Strategy 15- Give gifts to H (goods, sympathy, understanding, cooperation)

2.3.2.2 Negative Politeness

Negative politeness is oriented towards the negative face of the addressee, his/her want that his/her freedom of actions unimpeded. While positive politeness can

be seen as the language of intimate behavior, negative politeness is seen as the language of respect behavior. As all the FTAs have an imposition on the addressee in some degree, negative politeness aims at minimizing this imposition by preventing the negative effects of FTAs. Positive politeness minimizes the social distance between interlocutors. On the other hand, negative politeness is used whenever a S wants to put a social brake to the conversation. Thus, negative politeness is a form of social distancing.

There are five super strategies of negative politeness and these strategies have some sub-strategies as listed below. Example utterances are given for each strategy and the expressions that present the strategies are presented in bold. These sample sentences are adapted from Brown and Levinson (1987) and modified by the researcher.

A. Be direct: The simplest way to convey an on-record message is doing it in the most direct way. However, as negative politeness tries to redress the H’s negative face, these FTAs need to be done not completely directly. Brown and Levinson claim that S must be able to be indirect and direct at the same time while doing the FTA. This leads to the construction of a hybrid strategy of conventional indirectness.

Strategy 1- Be conventionally indirect: In this strategy, S needs to give an ‘out’ to H by being indirect and also go on record. This can be done by using contextually unambiguous meanings which are different from their literal meanings. The utterance goes on record in that way and S shows that he/she wants to go off record. Gordon and Lakoff (1971) claim that while making indirect speech acts in English, felicity conditions are needed. For a felicity condition, H must be able to comply with S’s wants or requests. If H does not know how to play the guitar, then there is no sense for S to ask H to play the guitar. There are some examples of indirect speech acts below:

- You couldn’t possibly / by any chance / I suppose / perhaps open the door, please.

- Are you by any chance able to give me a ride? - Do you want to cook for me?

- Is there permission to take your dictionary for a minute? - This isn’t sufficiently salty.

- What would you say if I ask you to do this for me?

- I don’t suppose I could possibly ask you for a cup of flour, could I? - There wouldn’t I suppose be any chance of your being able to give

me your dictionary for just a few minutes, would there? - Do you mind if I smoke here?

- Why don’t you prepare dinner for us? - How do you feel about going for a walk?”

B. Don’t presume/assume: In this strategy, S avoids presuming or assuming that anything involved in the FTA is desired or believed by H. This does not lead to presumptions about H, H’s negative face wants or desires.

a. Make minimal assumptions about H’s wants, what is relevant to H

Strategy 2- Question, hedge: Hedges are the expressions of doubt in relation to the propositional information provided (Hyland, 2000). Hedges in conversations convey a cautious approach to the speech acts. Skelton states that “it is by means of hedging system of a language that a user distinguishes between what he/she says and what he/she thinks about what he/she says” (p. 38). Similarly, Brown and Levinson (1987) define “hedge” as “a particle, word or phrase that modifies the degree of membership of a predicate or noun phrase in a set; it says of that membership that it is partial, or true only in certain respects, or that it is more true and complete than perhaps might be expected” (p. 145). Hedges are the most important linguistic elements of satisfying S and H’s faces. Hedging expressions can be done by prosodics, particles, lexical items, parentheticals, full adverbial clauses and other means such as complements of expressions like “I guess, I suppose that”. ‘If’ clauses pragmatically function as hedges on the force of speech acts. There are some hedged expressions below:

- You like it, don’t you? - I wonder if you can help me. - Perhaps you may come with me.

- Could it be possible for you to clean here? - I suppose you may not smoke here.

- That’s just how it is in fact. / in a way. / in a sense. / as it were. / in all probability. / I shouldn’t be surprised. / it seems to me. / don’t you agree?

- Help me if you can. / if it doesn’t matter. / if you don’t have anything to do. / if you want. / if I want you to.

- Would you lend me your car if I may ask you? / if you forgive my asking? / if you want to help me? / if you don’t mind?

- I think / believe / assume you can do me a favor. - As you and I both know, it is your turn to clean home. - Since it has been on my mind …

- Now it is probably the time to say good-bye.

- I don’t know whether you are interested, but there is a new film if you would like to watch with me.

- By the way, if you can get some milk, I would be grateful to you. - In case you want to know, I will be back soon.

- If you care to know, I love you.

C. Don’t coerce H

a. Give H option not to do act - Be indirect

- Don’t assume H is willing or able to do the act - Assume H is not likely to do A

Strategy 3- Be Pessimistic: This strategy “gives redress to H’s negative face by explicitly expressing the doubt that the conditions for the appropriateness of S’s speech acts obtain” (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 173). There are three important realizations of the strategy “Be pessimistic”: the use of the negative (with a tag), the use of the subjunctive and the use of remote-possibility markers. There are some examples below:

- You wouldn’t have brought something to eat, would you? - I don’t imagine there’d be any chance of you to do this for me. - I don’t suppose there’d be any possibility of you to come here. - Perhaps you’d care to give me some money.

- You couldn’t possibly lend me your car?

- You don’t have any time, do you by any chance?

b. Minimize threat

Strategy 4- Minimize the imposition: In order to give deference to H, S tries to minimize the seriousness of the imposition in his/her expressions. S needs to use expressions to minimize the imposition on H. In English this is achieved by expressions like:

- I just want to ask you if I can borrow a tiny bit of paper.

- I just dropped for a minute to ask you if you have any time for a just small cup of coffee.

- Could I have a taste of that cake? - It’s nothing.

- Nothing, I just want a little paper.

Strategy 5- Give deference: While giving deference, S either humbles or abases himself/herself or S raises H. By doing so, S tries to give message to H that H is of higher social status than S. Many languages have honorific systems to give this deference. Honorifics are direct grammatical encodings of relative social status between participants or between participants and people or things referred to in the communicative event. They directly or indirectly convey a status differential between the Ss and the Hs. In English, expressions such as “Sir, Mr, Mrs” are used as honorifics. Also, using titles of people while talking about them is an expression of honorifics.

Deference phenomenon is not only restricted to language structure; they are also expressed in language usage. One can do this by humbling himself/herself, his/her capacities and possessions. There are some examples below cited from Brown and Levinson (1987):

- It’s not much, I’m afraid, but it’ll fill your stomachs. (While serving a meal)

- It’s not much, it’s just a little thing I picked up for song in a bargain basement sale in Macy’s last week, I thought maybe you could use it. (While giving a present)

- I think I must be absolutely stupid but I simply can’t understand this map. (While asking for help)

D. Communicate S’s want to not impinge on H: In order to satisfy H’s negative face demands, S takes them into consideration and communicates with H in this way. He refrains from any infringement of H’s territory and face wants. This strategy can be achieved in various ways which comprises the negative politeness 7-9.

Strategy 6- Apologize: By apologizing, S shows his/her reluctance to impinge something on H and so he/she satisfies the negative face demands of H. There are four ways of apologizing:

Admit the impingement: S can use expressions to show that he/she is impinging on H.

- I’m sure you don’t have any time for me, but I need your help. - I know this is a bore for you, but I’d like to ask you a few questions. - I’d like to ask you a big favor.

- I hope this isn’t going to bother you too much but I need take this.

Indicate reluctance: S uses expressions or hedges to indicate that he/she is reluctant to impinge on H.

- I wouldn’t ask you to do this but I have no other solution. - Maybe I’ve come to the wrong person about this matter. - I don’t want to interrupt you but I need a second. - I hate to impose, but can you finish this?

- I’m terribly embarrassed to have to admit …

- I hesitate to trouble you, but I need to ask you something. - You’ve never bothered me, I know, but I need your help. - I hope you don’t mind me saying this but …

Give overwhelming reasons: S needs to give rational reasons for doing FTA and he/she shows that he/she doesn’t aim at infringing H’s negative face.

- I can think of nobody else who could help me. - I simply can’t manage to do all this work alone. - I’m absolutely lost in this project.

- I can’t understand a word of this language.

- Can you possibly help me with this because there’s no one else I could ask?

Beg forgiveness: S asks for acquittal for doing FTA and begs forgiveness from H.

- Excuse me, but…

- I’m sorry to bother you but… - I hope you’ll forgive me if… - I beg your indulgence…

a. Dissociate S and H from the particular infringement: While doing the FTA, S implies that he/she is not alone or S is not the person doing the act.

Strategy 7- Impersonalize S and H: Avoid the pronouns ‘I’ and ‘you’

Performatives: By taking the performative verbs and the subjects from the sentence, FTA can be avoided.

‘It is so.’ instead of ‘I tell you it is so.’

‘Do this for me.’ instead of ‘I ask you to do this for me.’

Imperatives: By omitting the subject ‘you’ in imperative sentences, S avoids the FTA.

Impersonal verbs: In some situations which may intrinsically be FTAs, agent deletion is done in the sentences. There are some examples below:

- It is obligatory to … - It is necessary that … - It seems that …

- It would be perfect … - It is not possible to do that. - It looks like …

Passive and circumstantial voices: Using the passive forms with some other structures may be used to redress the negative face wants of H. In English, this can be achieved by some expressions like that:

- It is regretted that …

- It would be appreciated if you could help me. - Let it be done.

- This needs to be done immediately.

Replacement of the pronouns ‘I’ and ‘you’ by indefinites: There are some impersonal versions of pronouns which can be used to prevent FTA.

- One shouldn’t do things like that. - Someone should help me.

- Ok, folks, let’s finish this work.

Pluralization of the ‘you’ and ‘I’ pronouns: S can use ‘we’ as the object instead of ‘I’ and ‘you’ subjects.

- We cannot accept responsibility about your belongings. - We regret to inform you that your request has been declined. - We feel obliged to warn you that …

Address terms as ‘you’ avoidance: While addressing H, using H’s name or ‘you’ as the subject gives H no out and this threats his/her negative face.

- Excuse me, Sir. - Hey, Mister.

Reference terms as ‘I’ avoidance: When there is distinction between man and office, S distances himself/herself from H. “In the English of kings, his majesty might say” (Brown and Levinson, 1987, p. 204):

- His majesty is not amused.

Strategy 8- State the FTA as a general rule: In this strategy, S does not want to impinge on H and tries to show the FTA as general rule, regulation or obligation. As S is forced to do or say the FTA. Corporate groups and corporations act like individuals by using this strategy. Here are some examples:

- Passengers are not allowed to stand here. - The committee requests the President …

- Later-comers are cannot be seated till the next interval. - We don’t memorize, we learn.

- Regulations require …

Strategy 9- Nominalize: Brown and Levinson (1987) have noticed that “degrees of negative politeness run hand in hand with degrees of nouniness” (p. 207). That is to say, using noun forms of words is called nominalization and it increases the degree of negative politeness. When the subject is nominalized, the sentence becomes more formal and thus more polite. There are some examples below retrieved from Brown and Levinson’s theory (1987):

- Your good performance on the examination impressed us favorably. Instead of:

- You performed well on the examinations and we were favorably impressed.

Instead of:

- I am surprised that you failed to reply.

- It is our regret that we cannot … Instead of:

- We regret that we cannot …

E. Redress other wants of H’s, derivative from negative face: The last higher-order strategy of negative politeness requires redressing some other wants of H. If H is at a higher hierarchy than S, then S respects H’s territory and preserve.

Strategy 10- Go on record as incurring debt, or as not indebting H: S can show his/her indebtedness to H by using some expressions in his/her sentences like that:

- I’d be eternally grateful if you would help me. - I’ll never be able to repay you if you … - I could easily do it for you.

- It wouldn’t be any trouble; I have to go right by there anyway.

2.4 Critique of Brown and Levinson’s Theory of Politeness

Meier states that “in spite of the existing frameworks and theories of politeness, there is still a disconcerting amount of divergence and lack of clarity concerning the meaning of the politeness” (p. 345). As politeness is such a complex phenomenon, it is not surprising that there is still lack of agreement among researchers.

All the different approaches and perspectives to politeness have some mutual relations about the concept or they are integrated with each other. The boundaries among these perspectives are not clear-cut at all. That is to say, other approaches to politeness either criticize some ways of Brown and Levinson’s theory of politeness or some scholars make references to their theory by supporting their views. The most common criticism for the theory is its universality of face. There are also some studies criticizing the underlying interrelationship between rational strategy and face. Also, some scholars have studied on the notion of Face Threatening Act. They have argued