CONNOTATIONS OF FURNITURE FROM ART NOUVEAU SCOTLAND TO CONTEMPORARY TURKEY:

MACKINTOSH’S LADDERBACK CHAIR

A THESIS

SUBM IHEDTOTHE DEPARTMENT OF

INTERIOR ARCHITECTURE AND ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN AND THE INSTITUTE OF FINE ARTS

OF BiLKENT UNIVERSITY

IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF

MASTER OF FINE ARTS

^aicr/in c/ccu

By ESRAGÜRAY January, 1994

NK

,Qn

I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Fine Arts.

_________________________________________________

Nur Altinyildiz (Co- Supervisor)

I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of M asjfr of Fine Arts.

~Ow.

Assoc. Prof. gizYener (Supervisor)

I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Fine Arts.

<x /,r.

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Yıldırım Yavuz

I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Rne Arts.

Approved by the Institute of Rne Arts

CONNOTATIONS OF FURNITURE FROM ART NOUVEAU SCOTLAND TO CONTEMPORARY TURKEY:

MACKINTOSH’S LADDERBACK CHAIR

ESRAGÜRAY

M.F.A in Interior Architecture and Environmental Design Co-supervisor: Nur Altinyildiz

Supervisor; Assoc. Prof. Dr. Cengiz Yener January, 1994

The aim of this study is to provide insight to the concept of furniture, and its everchanging connotations, as a prominent category of design. In this respect. Mackintosh’s Ladderback chair, being renowned as a classic piece, offers the means for description of such transfiguration process through time, culture and place. This comparative study, of its initial context and contemporary implications, intends to reveal the reasons of its esoteric composition as well as the meanings and intentions for its selection within contemporary interiors. Thus, this aspect will also bring forth tendencies regarding furniture production and acquisition in Turkey, particularly after the 80’s.

Key Words: Furniture, C. R. Mackintosh, Ladderback Chair, Contemporary Interiors, Connotations of Furniture.

ABSTRACT

ART NOUVEAU İSKOCYA’SINDAN GÜNÜMÜZ TÜRKİYE’SİNE MOBİLYADA A N U M DEĞİŞİMLERİ: MACKINTOSH’UN YÜKSEK ARKALIKLI SANDALYESİ

ESRAGÜRAY

İc Mimarlık ve Çevre Tasarımı Bölümüt Yüksek Lisans

İkinci Danışman; Nur Altınyıldız Danışman: Doç. Dr. Cengiz Yener

Ocak, 1994

Bu tezin amacı, mobilya kavramına ışık tutmak ve buna bağlı olarak tasarımın önemli bir kolunu oluşturan mobilyanın değişen anlamlarına işaret etmektir. Mackintosh’un Yüksek Arkalıklı sandalyesi, klasikleşmiş olmasından dolayı zaman, kültür ve mekan ilişkilerini açıkça ortaya koyan bir araç olarak seçilmiştir. Tasarlandığı dönem ile bugünkü yüklendiği anlamların karşılaştırilmasi; özgün tasarımının arkasındaki nedenleri ortaya koyarken, mekan içindeki yerini belirleyen kavram ve nedenlere değinmeyi hedeflemiştir. Bu nedenden dolayı da, son yıllarda Türkiye’de mobilya üretimini ve seçimini etkileyen ölçütleri de açığa çıkarmayı amaçlamaktadır.

ÖZET

Anahtar Sözcükler: Mobilya, Makintosh, Yüksek Arkalıklı Sandalye, Çağdaş İç Mekanlar, Mobilyanın Taşıdığı Anlamlar

First and foremost, I would like to express my indebtfullness to Nur Altnyildiz, who through her immense contribution of knowledge and advice, with praiseworthy encouragement, made this work possible and all the more enjoyable. I, also would like to thank Assoc. Prof. Dr. Cengiz Yener for his cordiality, guidance and interest throughout my thesis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Finally, I wish to express my gratitude to my sister Selin Giiray, without whose irreplaceable effort, I would not have been able to put forth this study. Special thanks also to Elif Erdemir, and all my other friends for their sincere help and continuous support.

ABSTRACT... iii ÖZET...iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS... v TABLE CONTENTS...vi LIST OF FIGURES...x 1 1NTRODUCTION... 1

2 THE MILIEU ACTING UPON MACKINTOSH... 4

2.1 Art Nouveau in England...4

2.1.1 Reaction to Industrialization... 6

2.1.2 Reaction to Historidsm ...8

2.2 Related Movements...9

2.3 Glasgow at the Turn-of-the-century... 15

2.3.1 Glasgow as an Industrial C apital... 16

2.3.2 Life in Glasgow... 18

TABLE OF CONTENTS

3 CHARLES RENNIE MACKINTOSH AS A SCOHISH ART

NOUVEAU DESIGNER... 22

3.1 Evolution of Mackintosh’s Artistic Style Through the Incidents of His L ife ... 22

3.1.1 Aspects of His Life and Major Influences...23

3.1.2 Principles of Mackintosh’s S tyle...31

3.2 Evolution of Mackintosh’s Style through His W orks...34

3.2.1 Architectural W orks...35

3.2.2 Interior Designs...41

3.2.3 Furniture Designs... 51

4 MACKINTOSH AS A DESIGNER OF CHAIRS...54

4.1 Materials and Production Techniques... 57

4.2 Classified Analyses of His C hairs... 61

4.2.1 High and Low-backed C hairs... 62

4.2.2 An Evolutionary Classification of His C hairs...63

4.2.2.1 1897... 65

4.2.2.2 1900... 68

4.2.2.3 1902... 70

4.2.2.4 1902-1904 ... 73

4.3 Chairs as Contributors to Spatial Compositions...79

5 REPRODUCTION OF THE LADDERBACK C H A IR ...85

5.1 Influences of Mackintosh’s S tyle... 85

5.1.1 Effects of Mackintosh on His Contemporaries...86

5.2 Reflowering of Art Nouveau... 97

5.2.1 Decorative A rts...98

5.2.2 Design and Furniture... 100

5.3 Reproduction of the Ladderback C hair...103

5.3.1 Legal Productions... 103

5.3.2 Illegal Productions... 108

5.4 Evaluation of The Ladderback Chair in Contemporary Interiors... 109

6 THE LADDERBACK CHAIR IN TURKEY...120

6.1 Furniture Sector in Turkey...120

6.1.1 Brief H istory... 121

6.1.2 General Tendencies in Furniture Acquisition... 123

6.1.3 Recent Tendencies in Furniture Acquisition... 124

6.2 Importation of the Ladderback Chair into Turkey... 126

6.2.1 Importation by M ood... 126

6.2.2 Other Importations... 128

6.2.3 Evaluation of Ladderback Chair as an Imported Item ...129

6.3 Reproduction of the Ladderback Chair in Turkey... 134

6.3.1 Initial Reproduction... 135

6.3.2 Recent Reproductions... 139

6.4 Evaluation of the Ladderback Chair in Turkey...143

6.4.1 U sers... 144

6.4.2 Designers... 146

REFERENCES... 153

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY... 159

APPENDICES... 161

APPENDIX A

Materials and Dimensions of The Original Ladderback C hair...161 Laddeback Chair in the Hill House... 163 APPENDIX B

Information from the Brochures of Ladderback Chair Reproduced by Cassina... 163 APPENDIX C

Dimensions of Various Reproductions... 167 APPENDIX D

LIST OF FIGURES

Fig.1 Furniture Warehouse By Honeyman,

Glasgow, 1872. (Buchanan, 1989)... 8

Fig. 2 Metal Plaques by The Four, 1896 1894 Painting by Beardsley (Howarth, 1977)... 11

Fig. 3 Work By The Four Vienna Exhibiton, 1900 (Howarth, 1977)... 13

Fig. 4 View From Glasgow University Tower, 1905 (Buchanan, 1989)... 15

Fig. 5 Glasgow School of Art Students in the Studio, circa 1900 (Grigg, 1983)... 20

Fig. 6 Poster by Mackintosh (Howarth, 1977)... 26

Fig. 7 Typical Scottish Townhouse Edinburgh 17th Cent. (Howarth, 1977)...28

Fig. 8 Watecolors by Mackintosh (Billcliffe, 1978)...30

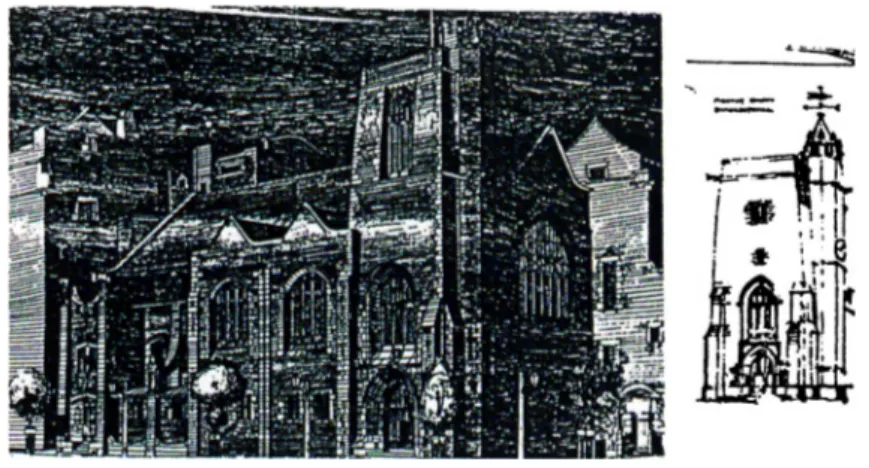

Fig. 9a Queens Cross Church, Glasgow (Howarth, 1977)...35

Fig. 9b Somersetshire Church, Sketch by Mackintosh (Howarth, 1977)... 35

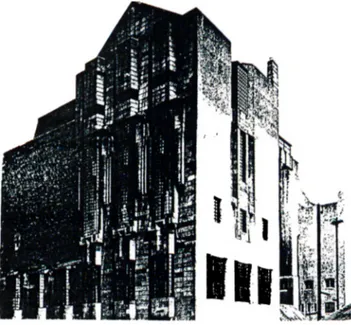

Fig. 10 Scotland Street School, Glasgow (Howarth, 1977)...36

Fig. 11 Martyr’s Public School, Glasgow (Howarth, 1977)...37

Fig. 12 Glasgow School of Art View from South-west (Howarth, 1977)...37

Fig. 13 Plan and North Elevation of The School (Howarth, 1977)... 38

Fig. 14a Airy and W ell-lit Studios (Buchanan, 1989)... 38

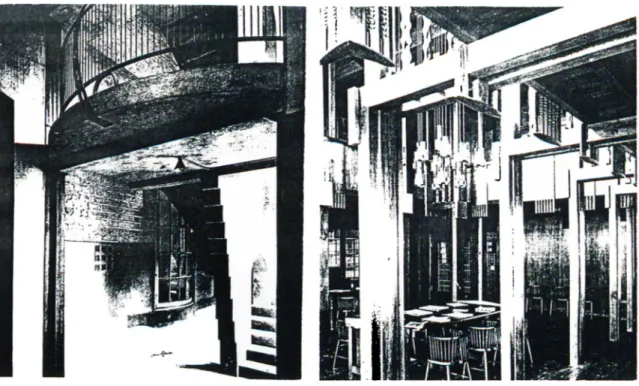

Fig. 14b West Wing Staircase (Howarth, 1977)... 39

Fig. 15 Library, Glasgow School of Art (Howarth, 1977)...39

Fig. 16 Symbols on the Railings, Glasgow School of Art (Buchanan, 1989)...40

Fig. 17 Windy Hill, Kilmacolm (Howarth, 1977)...40

Fig. 18 Hill House, Helensburgh (Howarth, 1977)... 41

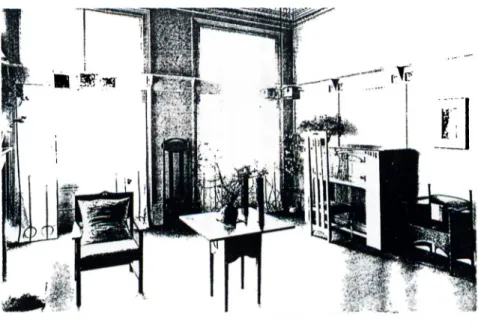

Fig. 19a Drawing Room, Mains Flat (Howarth, 1977)... 42

Fig. 19b Dining Room... 43

Fig. 19c Bedrooms... 43

Fig. 20 Contemporary Interior Sonbourne Residence, London, circa 1890...43

Fig.21 Drawing Room, Kingsborough Gardens, Glasgow (Howarth, 1977)... 44

Fig. 22a Drawing Room, Hill House (Howarth, 1977)...46

Fig. 22b Fireplace, Hill House...47

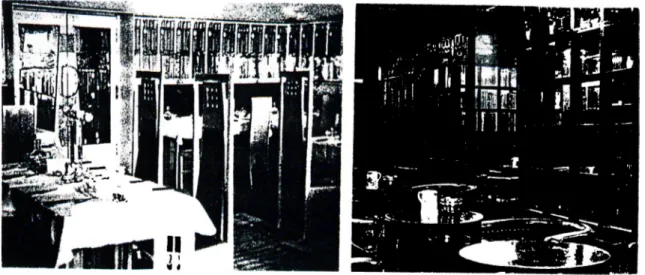

Fig. 23 Buchanan Str. Tearooms, Glasgow (Howarth, 1977)...48

Fig. 24 Argyle Str. Tearooms, Glasgow (Howarth, 1977)...48

Fig. 25 Willow Tearooms, Glasgow (Howarth, 1977)...49

Fig. 26 Ingram Str. Tearoom, Glasgow (Howarth, 1977)...49

Fig. 27a Lounge Hall, Derngate (Billcliffe, 1990)... 50

Fig. 27b Guest Bedroom, Derngate... 50

Fig. 28 Silver Painted Furniture, Room De Luxe (Billcliffe, 1990)...60

Fig. 29 Low and High Backed Tub Chair, Argyle Street Tearooms (Allison, 1974)...66

Fig. 30 Chair with Oval Backrail (Allison, 1974)... 68

Fig. 31 Chairs with Low/Medium/High Back Ingram Tearooms (Allison, 1974)...70

Fig. 32 Chair and Arm Chair Painted White Turin exhibition (Allison, 1974)... 72

Fig. 33 Room De Luxe Chair, Willow Tearooms (Allison, 1974)...75

Fig. 34 Dining-room Chair, Willow Tearooms (Allison, 1974)...75

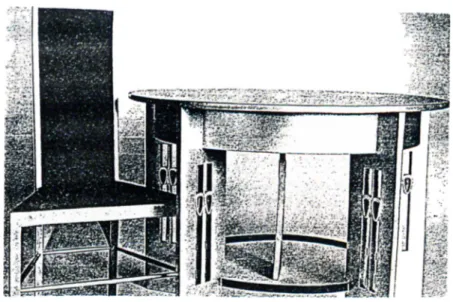

Fig. 36 Ladderback Chair, Hill House (Allison, 1974)...77

Fig. 37a Ladderback Chair articulates the room (Howarth, 1977)... 80

Fig. 37b Curved Back Chair divides the room... 81

Fig. 37c Chair With the Tapered Back defines the linearity... 80

Fig. 38 Ladderback Chair on the Landing, Hillhouse (Tahara, 1988)...83

Fig. 39 Hill House, Interiors (Tahara, 1988)...83

Fig. 40 Mackintosh’s Ladderback Chair in a Doll House...85

Fig. 41 F. L. Wright’s Furniture...88

Fig. 42 The Rose Boudoir Room Turin Exhibition (Grigg, 1983)...90

Fig. 43 Chair by Hoffmann...92

Fig. 44 Glasgow School of Art (Buchanan, 1989)... 95

Fig. 45 Mains Rat Interiors, Glasgow (Billcliffe, 1990)... 96

Fig. 46a Pepsi Cola Ad, by Alcorn 70’s (Haslam, 1989)... 99

Fig. 46b National Book Week Poster, by Max 1969... 99

Fig. 47 Habitat’s Strasse Furniture line Strasse (Sparske, 1986)...102

Fig. 48 Furniture by Eero Saarinen, circa 1960-70 (Fiell, 1991)...103

Fig. 49 Cassina Mackintosh Serie...104

Fig. 50 Willow Chairs in S.O.M Office, L. A 1993...105

Fig. 51 Production Techniques, Cassina... 106

Fig. 52 Identity Card, and Quality Check... 106

Rg. 53 Production Techniques... 107

Fig. 54 Ladderback Chair as Reproduced by the French Rrm Coherence... 109

Fig. 55 Residence in Manhattan, 1981 Interiors by Joe D’urso (Bluth, 1981)... 111

Fig. 56 Residential interior Fallowfield, London, Interiors by D. Stephen and Partners 1993...112

Rg. 57 a,b North American Tasei Corp., Chicago

Interiors by Perkins and Will, 1990 (Maserjian, 1990)... 113

Rg. 58 Washington D. C. Law Rrm, Interiors by Studios, 1993 (Cohen, 1993)... 114

Rg. 59 Contemporary Italian Interior... 115

Rg. 60 Drysdale Residence, Washington D. C. Interiors by Mary Drysdale, 1993 (Geran, 1993)... 116

Rg. 61 Ricardo Bofill Residence, Interiors by Bofill, 1989 (Halje and Weisskamp, 1989)... 117

Rg. 62a,b Maison Tonini, Toricella, Switzerland By Reichlin and Reinhard, 1972-4 (Jenks, 1987)...118

R g.63 Ladderback Chair produced by Camel...128

Rg. 64 Ad from a Periodical featuring Trademarks, 1992... 132

Rg. 65 Geometric Resemblances...139

Rg. 66 Residential Turkish Interior, Istanbul, 1992... 146

1 1NTRODUCTION

As furniture is a prominent category of design, an integral component of living, the ideological patrimony behind its unique composition and the implications of its specific spatial allocation become all the more significant Thus, Mackintosh’s Ladderback chair, with its unique design -for it is far removed from the traditional forms, and with its powerful presence, for it most readily attracts attention amidst any spatial scheme, presents one of the most distinguished examples.

Designed by Mackintosh in Scotland, the Ladderback chair has indeed transcended both time and space, as it still proclaims the originality of its design almost after a century. Having been accepted as one of the timeless pieces of this century’s design heritage, the purposeful selection of this chair aims to ponder upon the conceptions and connotations of furniture. The validity of this selection has been reiterated by Buchanan, who considers the Ladderback chair to constitute a significant contribution to current design search -as a masterpiece.

"Mackintosh’s most singular characteristic for .... designers, now and then, is his astonishing, ability to reshape everyday objects

and transform them into iconic images of great potency. His objects... are unique and memorable with a powerful, physical presence lacking in the artifacts of the heroic modern, (w hich)

sought for anonymity rather than individuality..." (1989:57)

As this search intends to recognize and tries to understand the reasons behind this piece’s appreciation as a "timeless classic" it involves a chronological, yet an inclusive approach which searches for meaning and value in the figurative aspect -from its initial context to its

production in the mid 70’s, and to its connotations in contemporary Turkish interiors. Such contemporary re-evaluation would provide the possible basis for understanding the still powerful presence of Mackintosh’s chair also in Turkey.

As the value of the object lies in its ultimate composition, the formal dignity of the chair resides for the greater part, in its initial origination. Therefore to better expound what the Ladderback chair has signified then, it is requisite to describe the historical milieu in which it was produced. As the first chapter aims to depict this essential background of its designer, the third chapter retraces all the artistic and individual phases of the designer himself.

Following Mackintosh’s design ideology in architecture, interiors and furniture, the next chapter concentrates solely on Mackintosh as a designer of chairs. This particularization intends to better define Mackintosh’s own perception of the item of chair in general and consequently to explore the Ladderback chair’s standing within this stylistic diversity of his chairs. All of the information, regarding these former chapters has been compiled from numerous published sources on Art Nouveau, Scotland, Mackintosh and contemporary furniture design.

Mackintosh had been quite bold to manifest a new style. As the Ladderback chair was a prominent piece of this design vocabulary, of pure and perfect lines, the repercussions of Mackintosh’s manifestation have to be accentuated. Since Mackintosh’s style, as a fusion, prepared the way for a broader twentieth century of Modernism, this imprint has lasted through a century, preparing the ground for the reappreciation of the Ladderback chair. Such has been explored concurrent with the revival of Art Nouveau in the 70s, as it has brought forth attention to both Mackintosh and this specific chair. To best express in Macleod’s words

the piece’s "autonomic existence" is validated in this part which consists of examples of its contemporary use in Europe and in the U.S.A.

As for the last chapter, since the Ladderback chair -reproduced or imported- has taken part within the Turkish furniture sector; a brief depiction of this sector intends to provide insight to the notion of furniture in Turkey. As this notion circumstantiates within Turkey’s own economic, cultural and artistic context, general tendencies regarding production and acquisition are both discussed in this chapter.

Such information , as very few reliable and up-to-date publications exist, has been founded upon interviews with numerous architects and interior designers and importers within the sector. The examples of its contemporary use, as well as general tendencies in its supply and demand, have also been compiled from periodicals.

As this chapter involves all the parties; its suppliers (designers, importers) and its demanders (purchasers, users); it explicitly defines the transfiguration of the Ladderback chair’s connotations; from its origin to its existence in a completely different cultural milieu and temporal context. Concurrently the change of context of this single piece of furniture throws light upon priorities and criteria regarding the selection of furniture in the latter case, i.e.Turkey.

2 THE MILIEU ACTING UPON MACKINTOSH

2.1 ART NOUVEAU IN ENGLAND

A brief delineation of Art Nouveau and its development in England is of elementary importance as it depicts the artistic background which was singularly conducive to the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. This contemporary exploration aims to give insight to intellectual and technical resources of its adherents. Since a sociological approach defines Art Nouveau as a coherent cultural phenomenon which took place at a specific point and place in historical time; the ultimate causes that provoked the emergence of Art Nouveau as a reflux (both to industrialization and historicism) should be specified to England.

However, a theoretical study of Art Nouveau in general, is primarily requisite, since it will characterize the avant-garde which Mackintosh had been a part. Hence, as every age has its own basic ideas that are absolutely basic to it, H.E. Hulme (cited in Harrison, 1991), has validated this point, where

"...certain doctrines which for a particular period seem not doctrines, but inevitable categories of the human mind.... (Men) ..never really conscious of them...do not see them. It is abstract ideas at the center, (taken) for granted, that characterize a period." (95)

The initial stages of Art Nouveau in Europe involved a symbolic return to the origins, focusing upon two fundamentai categories of nature (origins of life) and histo ry (origins of culture). The former was as a consequence of revolt against industrialization and latter against blunt

historicism. Both cases were immediately effective in England, as it was the first country to experience both industrialization and eclectic historicism prevalent at the time.

Art Nouveau for its aesthetic strife to confront mechanization and mass production, aimed to apply artistic principles to practical uses. In confronting historicist styles. Art Nouveau attempted to establish a new form language of universal application, aiming to redefine the social role of the artist in its difficult-to-grasp status at the time.

1

With respect to this. Art Nouveau, also encompassed the use of abstraction, rationality, logic and a linear form language which included organicism, and asymmetry. Towards the end of the century this has resulted in a unique combination of both rectangular and curved forms in the artistic sphere. This movement has also generated a certain preoccupation with the notion of synthesis (Eadie, 1990);

- synthesis of work of art and architecture, where the idea of content was to be unified with the total work of art,

- synthesis of all arts, crafts, industries and architecture, and - synthesis of intellect and emotionality.

On the account of these. Art Nouveau can be considered to be quite progressive with its desire to transform the environm ent along such encompassing synthesis of intellect, art, craft and architecture. This has had an irreversible impact in interior design, having sown the seeds of a broader style of modernism.

Influences acting upon Art Nouveau gave rise to something specific and different in each country.This matter has been stressed by Madsen (cited in Eadie, 1990), who distinguishes four different aspects of Art Nouveau form, conditioned (to a certain degree) by nationality.

"(1)an abstract and plastic conception (Belgium) ,(2)a linear and symbolic aspect (Scotland) ,(3)a floral and markedly plant inspired style (France), and (4)a constructive and geometrical style (Germany and Austria)." (54)

Commenting on this view, J.R. Taylor (cited in Eadie, 1990) sets apart "British" from Continental Art Nouveau, and refers to the aspects of "geometrical severity and simplicity" of the former, particularly of Mackintosh. According to him, these were consequential to the re-evaluation of England’s nationalistic past that resulted with the vigourous reactions against historicism.

Such has been unique to England as the disenchantment with industrialization, had been much more widely and severely felt compared to Europe. This point has been influential in reinterpretation of cultural historical values. However, in Britain a fully fledged continentally influential style, as distinctive as in Europe, was not really established. The artists instead continued the cultivation of individual styles, founding upon these former ideas of reaction to industrialization and historicism (Eadie, 1991).

2.1.1 Reaction to industrialization

"It is historic irony that the nation that gave birth to the industrial revolution, and exported it throughout the world, should have become embarrassed at the measure of its success." (M.J. Wiener cited in Briggs, 1985:185)

Exploration of reaction to industrialization is indispensible for understanding the course of Art Nouveau in England. Features of this British experience has to be thoroughly stated, as although providing the basis, England has suffered through it severely in growing discontentment

During the course of the nineteenth century, Britain became the "workshop of the world". Hence, behind every aspect of the Victorian Age, -the politics, science and art, "behind the fortunes of the rich and the misery of the poor", the variables of the industry (factories, steam-engines, foreign trade and the investments) emerged (Richards and Hunt, 1983). Due to the further strains this placed on every aspect of daily life, the prevalent view gradually becoming more pessimistic, industrialization resulted only with a strong revulsion to it Consequently, during the second half of the century, the earlier enthusiasms for technology was replaced by the concerns of the "social evils" brought by the Revolution (Wiener, 1985).

These emanating social mutations and spontaneous outburst against industrialization has had individualistic influences. Comments of Simmel (cited in Eadie, 1990) and May (1987), giving concrete historical and psychological content clearly illustrate the fundamentality of this coherence of socio-cultural trends with the inner needs and responses of the individuals, particularly artists.

This affirmation is vital to the origination of Mackintosh’s intellectual style. Since these pessimistic views are cardinal his innovative style can be based on this artistic atmosphere which sought relief. As the attention had been drawn to the phenomenon of decadence, ensuing from the retreat to the inner sphere as an individual, socially this did prompt a "th irs t fo r stylisa tio n" (Eadie, 1990). Hence, the determination to survive was soon to be manifested in an artistic (individual) and architectural (social) renaissance, inspired by the countryside, native traditions, and craftsmanship.

Although, affected by much deeper indigenous toctors, this has been valid for Scotland (Glasgow), where Mackintosh’s style had emerged and where he practiced for all his professional life. Reasons specific to Glasgow will be discussed in 2.3.

2.1.2 Reaction to H istoricism

In its efforts to escape from the reality of daily life, degraded by industrialization, Art Nouveau called attention to the issues of archaism, historicism and eclecticism, which were at the time predominant particularly in England. However, initially this "ahistorical mode of perception" as a reaction against confirmed and habituated style of life, manifested itself in a dilemmatic manner. In Tate’s (1986) opinion, reaction to historicism emanated from the idea of contemporary, functional work - which was to be of the day and therefore n o n -h isto rica l. On the other hand, contrary to this non-historic tendency, there also ensued a sym bolic return to both natural and cultural o rig in s .

In this respect the movement intended to establish contact with the original tra d itio n s , with the belief that they had been secluded behind the period styles. This was significant in England, as the buildings, imitating period styles blindfoldly, failed to suffice the contemporary functions which did not exist in the ages from which they were borrowed. (Fig. 1) Pevsner

(cited in Howarth, 1977: Mix) portrays the situation.

"...second half of the century saw a time of questioning and uncertainty ...(as) architectural design had become largely two dimensional and divorced from reality, it had been reduced to a system -the arrangement of a given number of symbols... within a prescribed area- the facade... Thought was directed at the style and archaeological exactitude of a building rather than its planning, convenience and suitability."

While some architects experienced refuge in eclecticism, others struggled against this rigid order, sowing the seeds of simultaneous alternative movements. Hence, oppositions to eclectic historicism and demarcations to separation of various styles, called attention to the search for the true m otives behind architectural appearance. Their effort was to create fresh, new images (Miyake, 1988). This has had further repercussions, as quality became associated with authenticity and newness, and significance was placed upon experimentation, inventiveness and imagination (Eadie, 1990).

Consequently, this non-historic approach, within the light of these former innovative aspects, prepared the ground for Mackintosh’s futuristic style, as an indigenous architect from Scotland. In his search for the origins of architecture Mackintosh, like many of his contemporaries, underpinned the opposition against eclectic historicism in Scotland.

2.2 Related Movements

"The question of relation between Art Nouveau and cultural movements that were important for the form which it took -symbolism, aestheticism, rationalism. Arts and Crafts- requires to be handled with some rigour because here we are not always dealing with easily specifiable historical sequences where one cultural 'development’ gives way to another." (Eadie, 1990:50)

In the light of this, the course of Art Nouveau in England, similar to the continent, presents a complex subject matter for an analysis of culture. This situation has had irreversible impacts on the avantgarde of the times, by means of its transitory overlap with other phenomena with which it may well share certain characteristics. Such occurrence first circumstantiated, when inspiration within the European avantgardiste rejection of classic realism, took different forms: Impressionism in France, Naturalism in Belgium, Pre-Raphaelitism in England and Jugendstil in Germany. Other prevalent movements -Symbolism, Aestheticism, Gothic Revival and, mostly. Arts and Crafts- were indeed all momentous in setting the artistic mood and influencing the innovative ideas of the precursors.

It would be appropriate to analyze each movement singularly, in order to better emphasize its theoretical aspects -realized in numerous forms of art works. Henrich Wolfflin, suggests like Semper before him, on the view that "the tendency of each age is best read in the smaller scale decorative arts" (Cited in Eadie, 1990).

Pre-Raphaelitism

Generating from the dissatisfaction with existing order of things, Pre-Raphaelites aimed to recapture the spirit of medievalism. Rossetti and Burne-Jones as its initiators, expressed mysticism and spiritualism in poetry and painting. The dominating concepts of melancholy and beauty were symbolized in vertical lines, trees and foliage.

Madsen (Cited in Eadie, 1990), considers the earliest Art Nouveau style in Britain evolving with Pre-Raphaelites, as he names Crane, Summer, Horne, Mackmurdo. E. Lutyens’ influences were major especially in interior design, as he developed a spatial system that distorted objects and caused them to appear out of context, and thereby making the familiar

seem strange. Lutyens has designed many houses in the rural regions of England, setting an influential tone especially in interiors.

Influence which Pre-Raphaelitism had on European Symbolism at the time, had also recaptured the imagination of Scottish designers. This was evident in the work (specifically in the mysticism and the sardonic malignancy of weeping females and innocent figures. Fig 2.) of The Glasgow Four, in which Mackintosh had taken part earlier (Howarth, 1977).

Fig. 2 Metal Plaques by The Four, 1896 1894 Painting by Beardsley (Howarth, 1977)

Symbolism

The context of Symbolism was preoccupied with the conveyance of a veiled essence of reality through the idea behind the shape, aiming not to describe observed reality, but rather to suggest the felt reality. Therefore, instead of addressing itself to the intellect, the symbol was to liberate itself to the intellect (Eadie, 1990). These aspects of avantgarde attempt to simplify form and to express the purely decorative value of two-dimensional shape became one of the

central factors of Art Nouveau in decoration. The exponents intended to provide means for the abstraction by emphasizing the sym bolic quality o f line. This has been exemplified by Crane, in England 1889,

"..line is all important let the designer...lean upon the staff of line- determinative, line emphatic, line delicate, line expressive..line uniting..."(cited in Eadie, 1990:77)

As for Mackintosh, he was intellectually impressed with another aspect, for he appropriated the Symbolists’ notion of the unconscious as the dom ain o f em otionality, it was due to this that Scottish Art Nouveau has searched for this "new instinctual tru th ". Yet this was quite esoteric, attributable again to Mackintosh’s nationalistic evaluations of this aspect. It encompassed uniquely Scottish means of "sensivity and inborn fee lin g" (Eadie, 1990).

Aestheticism

Many artists sought an escape from the miseries of industrialization in a philosophy of aestheticism. Marked by a mood of bitter-sweet melancholy, it found its expression initially in the works of Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley, as Felling (1960) reckons. The aesthetic movement, as it was too intellectual and too foreign in its inspiration to attain wide popularity, did not harmonize with Arts and Crafts in terms of social reform. Nevertheless, it exerted tremendous influence. The adjective art came into use as an indicator of sensitive design and equally beauty -art textiles, art pottery, art wallpaper art furniture were made in 1870s and 1880s.

"...(yet) failures in taste were frequent and by 1890’s the reaction against heaviness and bleakness had over reached itself. Rooms were now being filled with too many pieces of furniture littered with ornaments." (Read, 1979:274)

Also the role of visually meaningful forms became a major principle in all kinds of art productions. In differentiating between the fine arts and applied arts, French artist Maurice Denis was able to stress the power of form in an art production. As this was considered to be present in a vase, or a chair, as in a painting, a new range of expressiveness for Art Nouveau practitioners had been developed regarding the conception of decorative content and visual meaning in interiors (Eadie,1990).

The graphic and decorative style of the early Mackintosh and his group (The Glasgow Four) in the 1890s, applied to interior decoration, quite clearly illustrates its debt to such aspects of the Aesthetic movement (Fig 3). The Scottish Movement, inevitably manifesting in its own synthesis, presented an uncommon tension between the practical and mystical.

Fig. 3 Work By The Four Vienna Exhibition, 1900 (Howarth, 1977)

Arts and Crafts

As deplorable conditions prevailed, so tlia t more goods could be produced, more rapidly for more people, art critics expressed disappointment at the poor quality of design of manufactures, while social critics on the other hand pointed to the poor conditions of the poor. English Arts and Crafts Movement initiated as an alternative to such an inhuman system depicted by industrialization (Miyake, 1988).

Objecting to the artificial distinctions in art, and against making the immediate market or possibility of profit, the primal concern of the movement was in feet the threats to 'tra d itio n ’. Ruskin and Morris, both staunch Victorians, recognized in the Industrial Revolution and its aftermath, a disconcern for the fine craftsmanship. In this sense, they reaffirmed the value of human life, enhancing the importance of fostering an atm osphere in w hich individuals could recognize th e ir own im portance. Efforts in fostering this ideal interior atmosphere, needless to say, focused further also on artistic merits:

"Morris’s great contribution to the development of English craftwork- his chintzes and carpets, wallpapers and furnishings famous for their simplicity of form, rich collaring and exquisite workmanship- had been truly remarkable in an age given over to vulgar commercialism..." (Howarth, 1977; 228)

Hence, Morris’s efforts, with W. Lethaby, A. Mackmurdo and Walter Crane as its best known advocates, grew into a general revival of handicrafts. This rejuvenassence included work by craftsmen in wood, metal and glass along with paintings and sculpture. It was indeed meaningful regarding the conception of art applied to life as a whole. J.D. Kornwolfl’s assessment of Arts and Crafts ponders upon another fundamental where new stress has been given to importance of function in the creation of forms, which Voysey was to call, "fitn e ss fo r purpose" (cited in Billcliffe, 1990).

Having established Arts and Crafts standards, as a paradigm of quality artistic design achievements, this movement has been most influential of all phenomenal styles for Mackintosh. He can be considered to be greatly influenced by its aspects of function, material and strength.

This being so, he is not to be evaluated in terms of the same criteria, as such had been a point of departure. In his works -architectural, interior and furniture- he has ascended all, establishing his distinctive style which was stripped of known dilemmas of these movements.

2.3 GLASGOW AT THE TURN OF THE CENTURY

The importance of Glasgow, both as a prosperous, and therefore as a vital city, in providing the appropriate background for Mackintosh, has to be fully evinced. While his prodigious talents enabled him to paint, to design, and to build, nevertheless the city he worked in provided the necessary atmosphere, generating new ideas in both science and the visual arts. In Buchanan’s (1989) view, his art has indeed been the supreme manifestation of Glasgow’s artistic creativity.

Contrary to what Howarth (1977) has explained. Mackintosh, cannot be abstracted from the socio-cultural circumstances which were generating at the time. It is for this reason that an accurate depiction of complete transformation of Glasgow, aims to explain the interweaving of artistic and technical, decorative and functional concerns of Mackintosh, having had a central role in his strife.

Having been the Industrial power-house” of a world-wide empire, in Glasgow, the economic resources of the city were gradually directed towards all kinds of artistic activities.

Relating such an upsurge of artistic energy to a world-wide situation, similar parallels can be drawn with the emergence of Wright and the Prairie School in Chicago, Gaudi and Catalan Modernismo in Barcelona, and Horta and Guimard and in Brussels and Paris;

”(they) served the same ...clientele who, deriving personal.... wealth from expanding trade and industry, sought new artistic expression to bolster their own distinctive way of living rather as had the rich

Florentine merchants of the Renaissance." (Buchanan, 1989:51)

2.3.1 Glasgow as an Industrial Capital

The consideration of the conditions of economy, emanating from contemporary technological innovations particularly in Glasgow, is of fundamental importance. It was the primal impetus that facilitated the revitalization process in art and architecture, unique, as contradictory as it may seem, to this industrial city.

Glasgow became one of the great industrial cities of Britain, it was second in population only to London at the beginning of the century. Entrepreneurs turned to heavy industry of coal, iron, and cotton spinning, and especially of shipbuilding along the Clyde River, bywhich, at the same time, provided the experience of the steam engine (Meisler, 1989). As it possessed an enormous amount of economic resources and it was claimed that there was almost no product which was not manufactured within the area encompassed by greater Glasgow.

Glasgow anticipated the new century as the municipal trading capital, supplying to the world (Fraser and Morris, 1990). Furthermore, the workforce, yet still labouring under paternalistic

employers, took great pride in its skills. Through the adoption of new technology, manufacture and methods of distribution, "Glasgow became the skilled men’s’ city ” (Fraser and Morris, 1990). It was through this great labour and its exclusive understanding, Glasgow was defined as both prosperous and proud.

Hence, the city’s prosperity fostered a significant renaissance of arts, where a great surge of creative energy and capital was directed towards painting, architecture, metalwork, photography and even embroidery (Buchanan, 1989). Wealthy individuals, being mostly local businessmen, acted as penetrating patrons of the arts, exemplary is the case of William Burrell:

"William Burrell...made a fortune not only from their shipping line which traded with India, China, Japan, Australia, the Baltic and the United States,;..buying and selling of ships,but (he) was to leave his great art collection, which included superb medieval tapestries, to the city." (Buchanan, 1989:147)

There was evident emergence of a style of upper bourgeois, and partly of the urbane-middle class. This was significant, as the likes and correlated life styles of the avantgarde, intellectuals and the bourgeois were to influence taste patterns (Eadie, 1990).

Although professionals and merchants accumulated wealth, Glasgow’s unique attributes of development at the time, were not solely conditioned by the economic context. Glasgow’s inevitable growth, proceeding rapid progression of industry, has had its permanent impacts on her society, (on an individual basis, as Scottish class still remained diverse) it has sown the seeds of a certain "intellectual im provem ent".

Contemporary society of Glasgow, imputable to this former aspect of improvement, had a significant influence on innovatory artistic movements in domestic means, herewith other institutional establishments around 1890 and afterwards. Soon this tendency towards intellectual bettering simultaneously reclaimed standards of living. This manifested itself in various aspects of life, -particularly in contemplation of national character and history. Pevsner has pondered on the issue as well, as he commented on national character:

2.3.2 Life in Glasgow

"There is the spirit of an age and there is the national character...the two can act in accordance and they can interfere with one another until one seems to blackout the other completely..

(Yet)...national character does not at all moments and in all situations appear equally distinct. The spirit of a moment may reinforce national character or repel it.. The national character of one nation may be more likely to seek expression in (a) particular field.." (Pevsner, 1988:21,23)

In the light of these, such has indeed been the case in Scotland. Hence, affected by industry, science and invention, major aspects of Scottish life focused on the idea of essential survival of Scottish character and nationalism. Scotland at the time, was considered to be a land with distinctive legal and political culture, since

"..at the turn of the century Scottish culture had already gained an uneasy position between self-imposed Anglicizing destruction and assertive renaissance... The period confirmed and recreated Scotland..." (Fraser and Morris, 1990:3)

Attributable also to the civic enterprise, in Glasgow, as Eadie (1990) has brought forth: influence of the "local patriotism ” (pride of being a local citizen) was one effective source of

encouragement to every kind of art work produced. In the sphere of architecture such national spirit prepared the basis for a new mentality. This new concept of visual ideology, was founded upon an all-encompassing theory of history, culture, nationality and architecture.

"Towards the end of the century,.. a serious attempt was made to revivify the Scottish vernacular and to awaken public interest in old Scots buildings...The initiator Sir Rowand Anderson ...adopted native forms -crowstepped gables, angle turrets, dormers and the like and used them with considerable style in an attempt to produce a modernized traditional style"(Howarth, 1977:93),

which later came to be renowned distinctively as Scottish Baronial Style.

On the other hand, other influential ideas existed within certain established institutions in Glasgow which helped to better the ground for artistic and architectural mentality, the Art School was attempting to unite art with technical skills, and the University was disseminating aesthetic theory. Meanwhile, the press was describing the potential for the beautification of the environment as a popular discourse.

As individualism, and therefore private enterprise and private property became the key concepts, (Harrison, 1991) importance of the act of building came to be one of the major issues. Notion of a beautified living environment clearly went beyond the commercialized exterior, as new concepts in interior design originated, in Glasgow, with its "affluent, fashion conscious middle class. Despite the wide variations of status, ”a home of one’s ow n" was something to aspire to, "high on the list of priorities was a house of suitable size and location" (May, 1987). In accordance with this emphasis on domestication of life. Art School as a prominent source of local influence, helped to promote this improvement, as seen in an 1897 newspaper article:

"Why not make our houses, our furniture.... everything about us as beautiful as considerations of property and utility will admit?.... a people ignorant of the grandly simple elements of art have no idea of. Beauty of form in an article of daily use is surely preferable to unmeaningless ugliness." (Eadie, 1990:133)

However, the potential for decorative art which was newly penetrating into public sphere had been acknowledged in Glasgow previously, since Glasgow Art Club and McLellan’s Galleries had been founded as early as 1860. The work of painters, Macgregor, Lavery, Henry, and Hornel, -known as Boys From Glasgow- found their way not only into these galleries, but into numerous tea shops, and business premises. As businessmen, stimulated by local pride, purchased these works, so did Glasgow Corporation as it actively fostered art education in the city (Howarth, 1950). All this was imputable to the amount of artistic impulse present in the Glasgow School of Art, as a place to educate artists, architects and designers for their contemporary roles (Fig. 5). Even though it was a part of a nationwide art school system with a common curriculum and common aims, nevertheless, it struggled to uphold a new standard in art "o rig in a lity even at the expense of excellence” .

Fig. 5 Glasgow School of Art Students in the Studio, circa 1900

In 1885, as nowhere else in Britain, this instinctive artistic impulse towards originality was further emphasized, as Francis. H. Newberry became the headmaster.

He immediately, desiring an intellectual and a cultural credibility for the School, oriented courses towards handicraft production. This was in regard to his attempts of "diffusion of art among the public, in order to recover its lost educational value". Newberry’s stress upon creative, experimental originality in his approach to art has been prominent in providing the "necessary fertile seed-bed" for Mackintosh’s style to flourish in Glasgow (Buchanan, 1989).

However, the phenomenon of Glasgow Art Nouveau, cannot be reduced to Newbery’s activities solely. The role of cultural dim ensions specific to Glasgow once more accentuates the city’s significance in providing the basis and the chances for the emergence and the recognition of Mackintosh’s style. This has been validated by the tea room incident * which was concurrent with the Glasgow’s Art Revival As one of his first commissions. Mackintosh was offered to design the interiors of various tea rooms in Glasgow, it was through these commissions that he was able to actually realize his ideals of design.

* During the complete transformation of Glasgow and its environs, the population grew at an alarming rate, in 1830 and 1860’s, eliciting the social problem of day-time drunkenness, as the unemployed spent lunchtimes in bars and pubs (Howarth, 1977). At the beginning of 1870’s, such was prevented by the establishment of teashops in low rented cellars and basemente. Mrs. Cranston, in 1892, has been its proprietor in her experimental attempts of establishing of one in the restaurant district of town. Including billiards, smoking, chess, and reading rooms, it was renowned as a community centre, for during midday it served as a business man’s club, while in the afternoon an appropriate randevouz for both sexes.

3. CHARLES RENNIE MACKINTOSH AS A SCOHISH ART NOUVEAU DESIGNER

3.1 EVOLUTION OF MACKINTOSH’S ARTISTIC STYLE THROUGH THE INCIDENTS OF HIS LIFE:

Mackintosh, as the ambitious, intellectual architect and art worker of his time, was yet the rare, "sui generis" (of its own kind) initiator of a unique and unprecedent style. As "no style ever conquered his personal artistic experiences and acquisitions", and nothing he has created singularly ever shows a total break with his own most personal creative expression (Alison, 1974). All this attributable to his novelty as a designer, his inventions were in fact the works of a stalwart individualist "who had risked eccentricity in order to manifest his originality" (Eadie, 1990).

As Mackintosh lived in an era where originality and individual expression gradually became the cardinal points of all art works, insights to both his personality and intellectuality, -ulterior forces behind his unique style- become even more imperative. His personality as an artist and intellect was formed by emotion and artistic response, therefore his actions were commensurate with social life, events and developments surrounding him. It is for this reason, that important aspects of his professional life and influential incidents of his personal life and associations should be thoroughly traced.

In brief, concurrent with these influences and their particular occurrences at specific intervals. Mackintosh, as he had the opportunity of expression in numerous artistic media, (graphics.

paintings, watercolors, decorative elements, furniture and mainly architectural elements), developed a unique style that he expressed through rudiments of his individual synthesis.

3.1.1 Aspects of His Life and Malor Influences

Professional life

In 1884, Mackintosh commenced evening classes at Glasgow School of Art, and was apprenticed to architect John Hutchison until he joined the firm of Honeyman and Keppie five years later. Both of these professional experiences were most influential. As no designer can shake off subconscious memory, training and custom altogether, his initial architectural works were representative of most buildings in Glasgow, "showing little if any marked originality". However, remarkable restraint in the use of stylistic motifs and ornament was slightly detectable even at this early stage along with the primary emergence of forms with a strong bias. According to Howarth (1977) and Walker (1968) the office work was divided into two parts;

" ..a concrete reflection of the differences of opinion an d.... approach between Mackintosh and ...Keppie (in no sense an original mind) ...Mackintosh though admired by younger man... a talented designer... the deeper implications of (his) work were not

recognized." (Eadie, 1990:134)

Prosaic and plain as he may be for he was obliged to work in the prevalent styles. Mackintosh was still a successful architect, having already been awarded several prizes. Most significant was a scholarship tour of Italy in 1891, for it enabled him to contemplate the art and architecture of Italy. It was an important opportunity, as in middle class British homes there existed a firm tradition of sending children to Italy on a cultural tour (Alison, 1974). As Mackintosh studied the buildings which every apprentice architect had been taught to regard

as central to a common European heritage (Howarth, 1977). He fully absorbed this European style, ironically only later to confront overt historidsm.

On his return, he worked on various architectural projects, winning a silver medal of Kensington Institute for his proposal of a science and art museum in 1892. Having been distinguished as a successful architect. Mackintosh’s individual urge to break away from the habitual, quite surprisingly, substantialized in different media, other than architecture. Combined with his personality, it had been these media that enabled him to express himself freely without the restrictions of the office, clients or the prevalent styles.

Firstly it is requisite to accentuate Mackintosh’s ideology on originality and expressiveness. Mackintosh’s interpretation of symbolism is of importance, as Symbolism was also the sole inciter for the Four. Symbolism, according to Mackintosh, should transcend secluded meanings and it should emphasize "the superiority of creative imagination" instead, because it is this power of imagination the artist possesses, which enables him to represent objects as he perceives them (Eadie, 1990). Creative imagination being the crucial concept, by which instinct is brought forth.

All this is evident in Mackintosh’s graphic works, bookplates, posters and murals as every motif had been employed with an allegorical meaning. Thus, this once more provides proof to his belief in the instinctual, fearless expressiveness. Such is best renowned by his well-known epitaph: "There is hope in honest error, none in the icy perfections o f the mere s ty lis t.."

C ollaborations

During this symbolist phase, it was not incidental therefore that Mackintosh formed the Glasgow Four with his close friend, Herbert Macnair and Margaret-Frances Macdonald

sisters. At the time they too were captured by the mysticism of nature and intense symbolism which was expounded by the sardonic malignancy of Aestheticism · through the works of decadent artists Wilde, Beardsley and Burne-Jones.

The Four experimented with stylized naturalistic forms of an unusual kind as they sought inspiration in the seed and the root, in subaqueous plants. Highly-stylized linear patterns of the group as their trademark, remained the same whatever the medium was (repouse metal, gesso, stained glass). Consequently this interpretation of their subject, mainly nature and stylized human forms, has been considered to be rare, especially in an age given over to commercialism on one hand and eclecticism on the other.

The Glasgow Style made its London debut at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition of 1896 (Howarth, 1950), creating a storm of controversy. In 1897, however, Gleeson White, editor of THE STUDIO, published a series of articles on their work and brought them prominently to the notice of artists and designers everywhere. It was due to such efforts that the group was asked to exhibit in Turin in 1902 and in Budapest and Moscow successively.

Although The Four was met with stout and intense hostility in their hometown -due mostly to their naked distortion of human forms considered as hints to perverse, explicit "sexuality, disease and degeneration" nonetheless their works and interiors were met with enthusiasm abroad.

As the members’ influences had been reciprocal at the beginning. Mackintosh unintentionally remained under the spell of the group for some time. Nevertheless, he used this opportunity in the decorative field as a testing ground for ideas and theories.

т /щ W ;? .. ^ л ,:; > *; А N :i;i.:i|ii· • l l U \ : i i l i ? THE SCOTTISH

/AU5ICAL REVIEW

ривш1Еоат1'Т,.лчмн r e n t TWO PENCERg. 6 Poster by Mackintosh (Howarth, 1977)

Yet, in differentiating Mackintosh’s work from that of the other members, Howarth analyses abstract and symbolist elements of his style. He focuses on narrow angular upright forms (Rg. 6) as they were absolutely exclusive to Mackintosh,

"Mackintosh appears to have been impelled by an urge to express growth -root, stem, branch and flower...(where) surging vertical lines invariably predominate." (Cited in Eadie, 1990:62,79)

However, different views prevail on the group’s influence, concerning especially Margaret Macdonald, for he married her in 1900. Like Billcliffe (1990), P. Morton Shand bitterly condemns Margaret MacDonald as one of the "principal stumbling blocks" in Mackintosh’s path:

" ...Her work shows litHe sign of development, ...an amorphous paradise from which Mackintosh himself might well have escaped. It is very probable that Margaret Macdonald,...was responsible for limiting her husband’s vision, for tying him more securely to the aesthetic movement, and encouraging him to dissipate his energies on work of comparative unimportance..." (Cited in Howarth, 1977:145)

In an objective view, regarding the extent of Margaret’s contributions in her feminine style, this may be considered true, for these were indeed a part of the bric-a-brack he dealt with when he might have consolidated his position both in the architectural and interior fields. Nevertheless, in the following years he was able to break away from such superfluous detail within his own style.

With regard to this well established style, aspects of his Scottishness and his preoccupation with the art of Japan have to gain further recognition, as the former influenced evolution of his concepts in architecture and the latter his concepts in interior design.

S cottishness

Born and raised in Glasgow, Mackintosh was first and foremost a Scotsman. At the time, Muthesis found "local and national Scottish character/spirit to be significant" in the context of explaining Mackintosh’s style (Cited in Eadie, 1990). Mackintosh’s works, regardless of size and artistic media, have all evolved from his subjective interpretation of his history and culture.

"... one might almost say its patriotic- Scottishness. But for Mackintosh there was no contradiction between being, at one and the same time, a Scot and a cosmopolitan... He was prepared to learn from wherever and whatever he was looking a t" (Alison, 1974:5)

Mackintosh remained remote and unsolitious to the monumentality of classicism. In his search for an aesthetic yet rational and functional style, he attempted to embody the linear sensivity of traditional Scottish architecture (Rg. 7). This indigenous style has indeed proved to be most appropriate for it comprised the suitable architectural elements with solidity and the structural thinking with its own functional layout. Mackintosh, himself, was in praise of Scotland and expressed his pride in his Scottishness,

"The indigenous tradition which has been the architecture of that same country of ours is not less Scottish than we ourselves are, nor less indigenous than our countryside,... our traditions and our political institutions.” (Mackintosh cited in Alison, 1974:87)

Fig. 7 Typical Scottish Townhouse

Edinburgh, 17th Cent. (Howarth, 1977)

Japanese influence

Ensuing from the fortuitous conjuction of industrial Glasgow’s direct relationship with contemporary Japan, particularly through shipbuilding, the painters of the 1860’s were influenced by the art of Japan prior to Mackintosh. As "Japonisme” along with the objects of art, became the vogue, books on Japan (C. Dresser’s Japan, Its Architecture, Art and Art manufacture, (1882-1886) E. Morse’s Japanese Houses and Surroundings, Bing’s periodical Artistic Japan), and Japanese prints were easily available, as well as other bric-a-brack (woodcuts, vases, parasols etc) in Glasgow (Buchanan, 1989). Mackintosh, inevitably had been exposed to this exotic, yet potent source of inspiration. Billcliffe defines how:

"In 1896, Mackintosh hung up reproductions of Japanese prints in his basement room, the houses depicted would have had a great effect on him." (1990:8)

Such impression was stressed by Alison (1974) as well, who commented that Mackintosh found inspiration in Japanese images and paintings. Mackintosh, applied such influences to his interiors, evident in his interpenetration of spaces and the use of open screens and paiütions.The careful positioning of furniture within a space and its delicate relationship with the vases of twigs and flowers that decorated his rooms are perhaps the most important elements of Japanese style to be seen in his work. "The unerring skill of the Japanese in assembling a perfectly balanced composition" with simple forms interacted with Mackintosh’s own imagination to produce a totally new style.

To Mackintosh, the Japanese house, with its freedom and spaciousness of open plan which was quite remote from Victorian houses with box like rooms and heavy draperies, presented a challenge as he intended to translate it into western terms. Grigg has commented similarly.

"Japanese attitude to decoration was the antithesis to contemporary late Victorian and Edwardian taste. It valued restraint and economy of means rather than ostentatious accumulation...

Where Western interior is extrovert, intended to display wealth and status of its owner...Japanese room is a place of reflective calm, paucity and quality of the contents invite contemplation."

(1983:17-22)

Eventually, it was the aspect of unity above everything else that Mackintosh appropriated into his style. He conceived each of his interiors as a unity,designing every small detail -carpets, lights, even fenders- to create "a room that is in itse lf a w ork o f a rt". Although he pursued his style in this all-inclusive manner ("art, architecture and crafts were one creative w hole") with the influences and instances indicated above, his architecture and interiors were never granted the appreciation they deserved from the local artistic sphere of Glasgow, and were met with social hostility.

Last Years

Perhaps on the account of this severe and harsh hostility towards him and his style, after designing numerous memorable interiors (furniture and decorations included) for tea rooms of Miss Cranston and executing several houses commissioned by local businessmen who supported his innovative style, Mackintosh q u it He devoted himself once more to painting, his own media for free expression. In fact, it was some sort of retrieval for Mackintosh.

Fig. 8 Watercolors By Mackintosh (Billcliffe, 1978)

Following his leave from the firm of Honeyman and Keppie in 1913, he moved to Suffolk and from there unto Chelsea, where he painted to earn a living. For a short period he went to Germany and painted solely flower pictures at Walberswick. Taken for a spy for his correspondences with Austria, he spent the rest of the War in London. From 1923 to 1927, Mackintosh lived in Port Vendres, France and this time concentrated on landscape painting. Of these French paintings with their surreal atmosphere, Billcliffe (1978) draws attention to hints of his loneliness: "Everywhere is deserted and eerie stillness pervades the pictures".

Nevertheless, those who knew him , had always been fond of his charismatic personality. However, his strong personality accentuated by few authors only, in my opinion has been the ultimate governing factor throughout his designs, regardless of time, size and place,

".... his supreme self confidence, his devil-may-care attitude and indefatigable industry, made him at once admired and respected... (he had the) virile blood of the Highlander..."

3.1.2. Principles of Mackintosh’s style

Even though Mackintosh has never been considered as a compelling theoretician, as he has not indited any written manifestoes apart from his few scribbles of speeches and lectures. He has nevertheless had firm and sound artistic ideals, to which he remained faithful to throughout his professional life. As he has expressed in his very own words, an artist was to have ideals:

"the man with no convictions -no ideals in art- no desire to do something personal, something his own, no longing to do something that will leave the world richer his fellows happier is no artist" (Mackintosh cited in Eadie, 1990:181)

Since Mackintosh considered himself primarily as an artist, his "intellectual approach" in architecture and arts should be discussed firstly. Muthesius, through his observations, has stressed the imaginative aspect of Mackintosh’s intellectuality, as he comments on the imagination "suppressed in English work, while in Glasgow it was imagination which drove the work". (Cited in Buchanan, 1989: 33-35) Therefore this aspect, in accordance with his ideology, encompasses all of his executed works, as his approach has been the same whatever the size of the commission -be it a single spoon or an entire interior.

Thus, in Mackintosh’s view, the artist can not attain to mastery in his art unless he is endowed in the highest degree with invention and imagination, for "true a if -in proportion, in form and in colour- is produced by emotion. Just the same, the intelligent understanding of the absolute and true requirements of a building or an object is also of primary importance. The latter aspect referring to the scientific knowledge of the possibilities and beauties of material and technical possibilities of construction constitutes the scientific part of Mackintosh’s "rich psychic organization". Subsequently, architecture and applied arts in modern society were to be involved with this intellectual endeavour which united reason with emotion. This is quite significant since the avantgarde at the time had experienced this duality of reason and emotion.

Mackintosh considered architecture as comprising social environment and sculpture and painting as secondary in occupying a cultural space. Pictorial and decorative applied arts, however, quite contrastingly served functions. Thus, decorative applied arts offered the essential and the appropriate sector for the possibility of uniting u tility w ith beauty.

With regard to this concept of utility Mackintosh has generated further rudiments, as he had this conviction about the central role of u tility in conditioning the nature o f construction and adornm ent com prising com positional form . Thus, dignity, beauty and variety were all sequentials of the correct application of utilitarian principles. Eventually such ideology that unified form, aesthete and utility, always remained consistent and central, forming the three basic fundamentals of his distinct style: strength, u tility and beauty (Howarth, 1977).

Of these three principles, strength , as it was a derivative of material and utility, implies the relationship between function and design. Yet, the principle of beauty has to be further explored for it embodies -by an intricate combination- three other subsidiary qualities: tru th ,

tradition, and decoration. For Mackintosh, beauty of an art work or a building comprised

truth -conditioned by criteria of function and proper use of materials, rejecting any unnecessary refinement

Importantly this had decisive implications for the consideration of historicism and eclecticism in architecture, for these considered truth as a primary quality. The use of historical styles as a mode of adornment, for Mackintosh, was the worst kind of "conservatism, (which) is often an excuse for mediocrity in design, ...(a) repetition of features which have only their age to recommend them” (Cited in Eadie, 1990:133).

For Mackintosh, in many ways, beauty was linked with tradition or the necessary homage of traditional cultural forms. Such has been his means of defiance to "stylistic historicism". Alison (1974) comments on this principle which involved Mackintosh’s synthesis of these chosen elements.

As for the concept of decoration, related to beauty, concerning both the material and

construction, he suggested that "the salient and most requisite features should be selected for ornamentation". Mackintosh’s sentiment on this matter, where beauty is plainness and bareness, commentates a sparing use of the emphasis of detail, as it is best summarized in his famous epitaph: "Construction should be decorated and not decoration constructed”.

The ideal was to be a "seamless" interweaving of structuration with decoration, as he frequently expressed that there should be no apparent break between the construction and the decoration of a house. As aesthetic effect of apparent construction is acknowledged, the significance of adornment is downgraded. This point was quite innovative in its emphasis of