KADİR HAS UNIVERSITY

GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES

ENERGY AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT DISCIPLINE AREA

THE ROLE OF IRENA

IN GLOBAL RENEWABLE ENERGY POLICIES

HAZAL MENGİ DİNÇER

SUPERVISOR: PROF. VOLKAN Ş. EDİGER

CO-SUPERVISOR: ASSOC. PROF. ÇAĞLA GÜL YESEVİ

MASTER’S THESIS

THE ROLE OF IRENA

IN GLOBAL RENEWABLE ENERGY POLICIES

HAZAL MENGİ DİNÇER

SUPERVISOR: PROF. VOLKAN Ş. EDİGER

CO-SUPERVISOR: ASSOC. PROF. ÇAĞLA GÜL YESEVİ

MASTER’S THESIS

Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Kadir Has University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s/PhD in the Discipline Area of Energy and Sustainable Development under the Program of Energy and Sustainable Development.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ……….. i

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ……… ii

LIST OF TABLES ………. iv LIST OF FIGURES ………... iv ABSTRACT ………... v ÖZET ……….. vi 1. INTRODUCTION ………... 1 2. SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIVISM ……… 8

2.1. A THEORETICAL OVERVIEW OF SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIVISM ……….. 8

2.2. SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIVIST VIEW ON INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS 11 3. INTERNATIONAL RENEWABLE ENERGY POLICY CONTRIBUTIONS ……. 14

3.1. BEFORE IRENA (1949-2002) ……… 14

3.2. ROAD TO IRENA ………... 17

4. IRENA ……… 26

4.1. PRESENT IDENTITY OF IRENA ……….. 26

4.2. THE STRUCTURE OF IRENA ……….. 28

4.3. PROJECT FACILITATIONS OF IRENA ………... 29

4.3.1. Global Atlas ………... 30

4.3.2. Project Navigator ………... 31

4.3.3. IRENA /Abu Dhabi Fund for Development Project Facility ……… 32

4.3.4. Sustainable Energy Market Place ……….. 34

4.4. INITIATIVES OF IRENA ……… 35

4.4.1. Clean Energy Corridors ………. 36

4.4.2. Coalition for Action .……….. 38

4.4.3. Global Geothermal Alliance ……….. 39

4.4.4. Parliamentary Work .………. 40

4.4.5. Renewable Energy Roadmap ……… 41

4.4.6. Renewable Readiness Assessment ……… 43

4.4.7 SIDS Lighthouses ……….. 44

5. EVALUATING IRENA WITH SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIVISM ……….... 46

6. CONCLUSION ……….. 56

i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would first like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Volkan Ş. Ediger who accepted me as a MA student at the Energy and Sustainable Development Master Program of Kadir Has University. I would also like to thank my co-supervisor, Assoc. Prof. Çağla Gül Yesevi for her guidance and direction since my bachelor studies at İstanbul Kültür University. Without the useful comments, remarks and suggestions of my supervisors, this thesis would not have been successfully completed. They always encouraged me to be my own person in my work, and pushed me towards the right path.

My thesis was also made possible in part by scholarships from the Kadir Has University and Heinrich Böll Stiftung Association, Turkey Representation.

My sincere appreciation also goes to my colleagues at Kadir Has University who stood by me, especially Melike Eken, Gözde Karagöz and Burak Şuşoğlu, whose encouragement and kind support I very much appreciate. I also owe Dr. John W. Bowlus a debt of gratitude for his help for correcting grammar. I would also thank to my dear friends for showing their understanding and love in helping me complete my thesis.

Last but not to least, I would like to thank my parents and brother, Remziye, Hayri and Umut Mengi, who always stand behind me with their best wishes. I finally extend my acknowledgement to my husband, Barbaros Dinçer who is thoughtful, positive and trusting.

ii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

ACEC The African Clean Energy Corridor ADFD Abu Dhabi Fund for Development AOSIS The Alliance of Small Island States

BMU German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety

BP British Petroleum (oil company) °C

CDU

The degree Celsius

Christian Democratic Union of Germany CECCA The Clean Energy Corridor of Central America CEM Clean Energy Ministerial

COP CSD

Conference of the Parties

United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development CSU Christian Social Union in Bavaria

EC

ECOWAS EU

European Commission

Economic Community of West African States European Union

EUROSOLAR The European Association for Renewable Energies

G8 The Group of Eight

G77 The Group of 77

GDP GGA

Gross Domestic Products

The Global Geothermal Alliance

GHG Greenhouse Gas

IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency IEA International Energy Agency

IGOs IISD

Intergovernmental Organizations

International Institute for Sustainable Development IOs

IPU

International Organizations the Inter Parliamentary Union

IRECs International Renewable Energy Conferences IRENA International Renewable Energy Agency ISEA International Solar Energy agency

iii JREC Johannesburg Conference, the Renewable Energy Coalition

MW MT NGOs Megawatt Million Tons Non-governmental Organization OECD OPEC

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development The Organization for the Petroleum Exporting Countries

REMAP Renewable Energy Roadmap

REN21 Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century RRA The Renewable Readiness Assessment

SDGs The Sustainable Development Goals SE4ALL Sustainable Energy For All

SEM The Sustainable Energy Marketplace SIDS The Small Island Developing States SPD The Social Democratic Party of Germany tCO2

UAE

Total Carbon Dioxide The United Arab Emirates

UK United Kingdom

UN United Nations

UNCED United Nations Conference on Environment and Development UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNFCC The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change UNSEGED United Nations Solar Energy Group on Environment and

Development

US The United States

WACEC West Africa Clean Energy Corridor WCRE World Council for Renewable Energy WSSD World Summit on Sustainable Development

iv

LIST OF TABLES

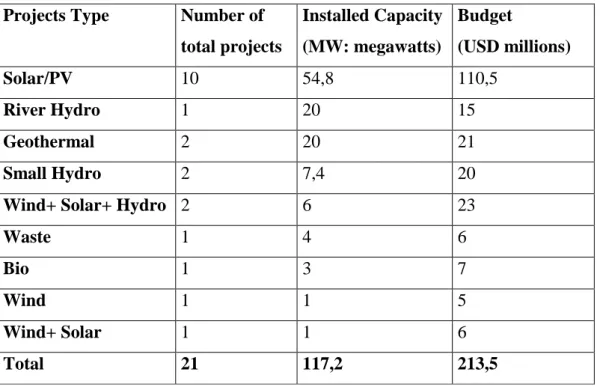

Table 4.1. IRENA/ ADFD selected projects ... Table 5.1. The main points of theory and comments ...

33 47

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1.1. Global primary energy consumption by sources ... 3

Figure 4.1. The members of IRENA by their membership years ... 26

Figure 4.2. The Number of IRENA’s initiatives by members ... 35

Figure 4.3. Projected primary renewable energy shares until 2030 ... 42

v MENGİ DİNÇER, HAZAL. THE ROLE OF IRENA IN GLOBAL RENEWABLE ENERGY POLICIES, MASTER’S THESIS, İstanbul, 2018.

ABSTRACT

It is widely accepted that renewable energy will make significant contributions to a more sustainable world because of its environmental, sociological and economic advantages. Taking this into account, a transition from a fossil fuel-dominated to a renewable-dominated energy system is inevitable. However, only 10.4% of world primary energy consumption today comes from renewable sources including hydroelectric power. It will therefore take a long time to implement international policy and effective action for renewable energy to become this dominant resource. States are the key actors of the international structure and the main decision-makers on renewable energy policies. At the same time, international organizations can help states to internalize and form new identities by creating norms. Within this perspective, it is expected that the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) will have a voice on international renewable energy policies. This study discusses how IRENA helps shape international renewable energy policy through its interactions with states and its with other international organizations. The study first examines the international community's road to IRENA with efforts to create renewable energy governance around the world. Then, it examines in detail the initiatives of the agency over the last 10 years, from its establishment to today, and the process of norm emergence and identity creation of IRENA on renewable energy through the social constructivism approach. At the end of the study, I argue that, despite its short existence, IRENA’s efforts to create norms were successful, but the agency needs to spread its initiatives more equally around the world, without reference to development classification, so that these norms become truly global and universal. Today, nearly every country needs to improve its renewable energy policies. It may only be possible for states to form a common identity on the internalization of norms and on renewable energy only in this way.

Key Words: IRENA, Renewable Energy Governance, Global Renewable Energy Policies, Social Constructivism, Transition into Renewable Energy

vi MENGİ DİNÇER, HAZAL. IRENA’NIN KÜRESEL YENİLEBİLİR ENERJİ

POLİTİKALARINDAKİ ROLÜ, YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ, İstanbul, 2018.

ÖZET

Yenilenebilir enerjinin, çevresel, sosyolojik ve ekonomik üstünlükleri nedeniyle daha sürdürülebilir bir dünya oluşumuna önemli katkılar sağlayacağı bilinmektedir. Bu durum göz önüne alındığında fosil kaynakların egemen olduğu enerji sisteminden, yenilenebilir enerji ağırlıklı bir sisteme geçiş kaçınılmazdır. Ancak, günümüzde tüketilen birincil enerji kaynaklarının sadece yüzde 10,4’ü yenilenebilir kaynaklardan –hidroelektrik dahil- sağlanmaktır. Bu kaynakların dünya enerji sepeti içinde egemen olması için uluslararası politika ve kararlı uygulamalarla uzun bir süreye ihtiyaç duyulmaktadır. Devletler uluslararası yapının temel aktörleridir ve yenilebilir enerji politikaları konusunda asıl karar vericilerdir. Bunun yanı sıra, uluslararası organizasyonlar da yenilenebilir enerji konusunda yeni normlar oluşturarak devletlerin politikalarında içselleştirmeye ve yeni kimlik oluşturmaya neden olabilmektedirler. Bu çerçeveden bakıldığında, Uluslararası Yenilebilir Enerji Ajansı’nın (IRENA) küresel çaptaki yenilenebilir enerji politikalarında söz sahibi olması beklenir. Bu çalışma, IRENA’nın yenilebilir enerji politikalarındaki rolü ile devletler ve diğer uluslararası organizasyonlarla olan etkileşimini incelemektedir. Çalışmada ilk olarak, uluslararası toplumun dünya çapında yenilenebilir enerji yönetimi oluşturma çabaları ile IRENA’ya giden yol incelenmiştir. Daha sonra, Ajans’ın, kuruluşundan günümüze kadar geçen 10 yıllık süre içinde gerçekleştirdikleri girişimler ayrıntılarıyla incelenmiş ve sosyal inşacılık (social constructivism) yaklaşımıyla IRENA’nın yenilenebilir enerji konusunda norm ve kimlik oluşturma süreçleri incelenmiştir. Çalışma sonunda kısa süreli varlığına rağmen IRENA’nın norm oluşturma aşamasındaki çabaları başarılı bulunmuştur, ancak oluşturulan normları geniş bölgelere yaymak için girişimlerini herhangi bir gelişmişlik sınıflaması yapmadan tüm dünyada eşit olarak sürdürmesi gerekmektedir. Günümüz dünyasında hemen her ülkenin yenilenebilir enerji politikasını iyileştirmeye ihtiyacı bulunmaktadır. Ancak bu şekilde, normların içselleştirilmesi ve yenilebilir enerji konusunda devletlerin ortak bir kimlik oluşturması mümkün olabilecektir.

Anahtar Sözcükler: IRENA, Yenilenebilir Enerji Yönetimi, Küresel Enerji Politikaları, Sosyal İnşacılık, Yenilebilir Enerjiye Geçiş

1 1. INTRODUCTION

Energy has long been a critical factor in the survival of human beings, almost as important as food, water, and shelter. Thus the quality, intensity, and conversion efficiency of energy have been one of the most prominent aspects of human beings (Smil, 1994). Solar, wind, water, human muscle, biomasses from wood and grass, agricultural residues, animal wastes, and finally fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas have been used as energy sources throughout the history (Solomon and Krishna, 2011).

Energy transitions occur from one dominant energy source to another because human beings prefer more affordable, efficient, higher quality and cleaner energy types as time passes and people gains experience. In hunter-gatherer societies, people generated energy from food, and human muscles were generally used to survive harsh climatic conditions and forces of nature. The only technical development of that time was the invention of fire. After that, as the second transition occurred in agrarian societies, people had to work more. Domesticated animals, as well as water and wind, were used as mechanical energy and for utilizing the activities of agrarian societies. At the same time, biomass, especially firewood and peat, was widely used for heating (Sieferle, 2001). Because of the slow and stable technical advancements in agricultural societies, the energy mix did not change appreciably, except for some European societies that extracted small scales of coal in rudimentary ways.

The third and the most crucial transition from biomass to fossil fuels, which started with a transition to coal, and later to oil and finally to natural gas began in the eighteenth century. Fuel-wood supply began to be inadequate because of deforestation and its calorific value. Initially, Britain began using coal in larger amounts, spurring the Industrial Revolution. Coal use then became widespread in the US, Sweden, Germany, Spain, China, India, Japan, and Turkey. The invention of the steam engine and the melting of the iron were the main technological drivers that increased coal use, and coal remained the dominant energy source until the 1970s (Smil, 2010). However, oil had gained importance in the twentieth century. Oil had advantages as it is denser in energy

2 content, easier to transport and cleaner than coal. Oil then gained superiority over coal with the invention of the internal combustion engine, and diesel and petrol engines became the prime movers (Bradshaw, 2013). Finally, natural gas gained relatively higher importance in the energy mix in the world, first in the US in the 1930s and Europe in 1970s, because it is cleaner as a combustible hydrocarbon for heating, and electricity. In addition to these fossil fuels, some other alternatives emerged in the form of hydroelectric and nuclear power (Smil, 2008, 2016; Bradshaw, 2013).

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, fossil fuels were used as dominant energy sources, while wood and hydropower were the dominant non-fossil fuels energies during the previous two centuries. Wood was used for heating, and hydro energy for generation of electricity in the resource-abundant countries. Since the late twentieth century, however, renewable energy gained new attention worldwide, and new policies were implemented to support their use. Nevertheless, the proper support mechanism for the prevalent use of renewable energy needs advanced technology and affordable prices. At present, there is an expectation that fossil fuels will be replaced by renewable energy sources (Bradshaw, 2013). Energy transitions always occur towards better energy sources, which have a higher calorific value, practicability in use and environmental friendliness. Hence, it can be stated that humans chose coal as the dominant source because it was more efficient than biomass sources and because they tried to stop deforestation. The same can be said about oil and natural gas; oil and natural gas became the dominant sources because they had more calorific value than coal and were cleaner. Nowadays, renewable energy use is predicted to increase because it is the cleanest energy type when compared to other sources.

It is evident that renewable energy offers several advantages over fossil fuels. Firstly, fossil fuels are limited, and the reserves are not abundant equally across the world. So, some countries are import-dependent and vulnerable to price fluctuations in the fossil fuels market, and supply security issues threaten especially the import-dependent countries. Renewable energy could reduce the overdependence on fossil fuel suppliers and could help oil-importing countries to increase their roles in international markets by creating a new source of economy. Secondly, via renewable energy, domestic and local development could be enhanced by local production that could be a solution for rural

3 development, and also create jobs and prevent domestic migration to big cities in developing countries. Above all, because of its cleaner nature, renewable energy is seen as one of the most influential solutions to combat climate change by reducing the consumption of fossil fuels and replacing it with lower carbon sources (Cruciani, 2013). The transition to renewable energy technologies from hydrocarbons is seen one of the most important solutions to combat climate change and keep down global warming under 2°C and to restrain it 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels parallel with the Paris Climate Agreement (UNFCC, 2015a).

However, fossil fuels still play an essential role of in the global energy mix (Fig. 1.1). According to BP Statistical Review of World Energy (2018), primary global energy consumption by sources is 57.5% oil and gas/hydrocarbons, 27.6% coal, 4.4% nuclear energy, 6.8% hydropower, and 3.6% modern renewable energies.

Figure 1.1 Global primary energy consumption by sources (BP, 2018)

Renewable energy technology has some problems because of their intermittency, which depends on geography and climate, which are a major barrier to their widespread acceptance. Renewables have a considerably higher price when compared to fossil fuels. Also, there is a lack of awareness that creates problems for the dissemination of renewable energy (Yaqoot et al., 2016). However, the transition to renewable sources is inevitable.

4 In order to fight the challenges derived from the use of fossil fuels, instruments such as technological advancements, new policies, strong markets and reformation of consumer behaviours are required. In order to phase out the use of fossil fuels and make a transition to renewables, coherent and robust governance at all political levels, including global levels, are needed (Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen et al., 2012). Governments are the main actors in creating renewable energy policies that primarily include setting apparent objectives; creating equal opportunities with fiscal incentives (tax credits, loans, and guarantees); designing portfolio standards, quotas, and feed in-laws or tariff mechanisms; and paying attention on rural development and electrification (El Ashry, 2012).

In order to move from the current unsustainable fossil fuel-dominated system to a sustainable, renewable energy system, civil society, international and regional organizations and partnerships need to make efforts around the world. However, it should be noted that intergovernmental organizations play also significant roles in energy policies (Florini and Sovacool, 2009). For this reason, the foundation of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) is a breakthrough in attracting the attention of international system actors (Esu and Sindico, 2016).

This thesis will discuss the role of IRENA in supporting global renewable energy policies by promoting the member state policies and fostering international cooperation. It uses social constructivism to evaluate the agency’s role across the policy-making process in its member countries. The main research question is "What is the role of IRENA in international renewable energy policies?" The sub-questions are listed below: “What is the importance of renewable energy in contemporary energy transition?”; "what is the importance of international organizations in the transition to renewable energy?”; “what are the differences between IRENA and these organizations?"; "what kind of tools does IRENA use for renewable energy transition?"; and “how are the agency’s activities interpreted by social constructivism?”.

The establishment of IRENA is defined as a milestone for the future of the world’s energy policies (BMU, 2009). In order to understand IRENA’s role in global energy policies, it is needed to form a historical background by using reports of international conferences as well as related literature on international institutions. The agency’s

5 activities, initiatives and tools are to be the primary source of the information, databases, and analyses on renewable energies and to encourage member countries, especially developing countries, to achieve targets for their energy transitions. For that reason, its activities are detailed by using its own website, social media accounts and official documents, in addition to open source, academic journals, books, newspapers. Studies on social constructivism are examined in detail to understand how IRENA could establish international norms for renewable energy.

In the literature review, firstly previous studies about IRENA are given; however, it should be recognized that the agency was established in 2009 and, because of its short history, there are few studies directly related to it. Existing studies generally make a comparison between IRENA and other international organizations on energy and environmental issues (Wright 2011; Graff, 2013; Urpelainen and Graaf, 2013; Esu and Sindico, 2016; Müller, 2017; Overland and Reischl, 2018). Wright (2011) is the first scholar to study IRENA, focusing on its statue, priorities, and objectives. Wright discusses the reasons behind IRENA's foundation, examines the agency's relations with other major international organizations as the United Nations (UN) and International Energy Agency (IEA), and evaluates the future potential of IRENA. In the end, he emphasizes that IRENA would be seen as a global voice for the transition to renewable energy. Meanwhile, Graaf (2013) focuses on IRENA’s role in global energy governance as a new actor rather than being part of an existing institution. Whereas the scope of the other international energy institutions is too broad, Graff commends IRENA for being a specific organization that directly relates to renewable energy. According to Urpelainen and Graaf (2013), the creation of IRENA is a success for institutional innovation; they use data to compare IRENA with other intergovernmental structures. While the establishment and availability of international organizations has slowed in recent decades, IRENA achieved to widen itself with rapid ratification rates. Esu and Sindico (2016) point out the significance of international organizations in the transition to sustainable energy sources. Thus, in the study of the rivalry and partnership of IRENA and IEA were analysed, eventually both organizations became considered as crucial for global energy transition. Müller (2017) identifies IRENA as a global actor and defines predecessor organizations of IRENA, which are dealing with renewable energy and could not identify themselves as global organizations because they were effective only

6 local in scope, allowing IRENA to fill a critical international gap. Most recently, the study of Overland and Reischl (2018) discusses the agency’s role in national energy policies by analysing the participation of representatives of member countries in assembly and council meetings. Studying member countries based on their public documents of IRENA and the other organizations as a reference, the study examines the influence of IRENA on member countries, in addition to this, the study compares IEA’s and IRENA’s reference rates on the national policy documents on specific countries. There are only a few studies on the policies of specific countries and regions. (Roehrkasten and Westphal, 2012; Yesevi and Tiftikçigil, 2017; Madichie, 2011). Roehrkasten and Westphal (2012) evaluate the importance of the agency especially in Germany as the second largest financial contributor and pioneer, because the country seeks to phase out nuclear and transition to renewable sources. It focuses on the early years and assesses the agency’s aims and activities for the enhancement of the organization. Roehrkasten and Westpal (2013) more comprehensively discuss Germany’s foreign policy role in the creation of IRENA. Yesevi and Yavuz Tiftikçigil (2017) evaluate IRENA and Turkey’s renewable energy policies. Madichie (2011) also studies the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) initiative on Masdar City as the headquarters of IRENA.

Wouters (2017) mentions IRENA’s role in international organizations, but emphasizes the agency’s specific activities such as Renewable Energy Readiness Assessment (RRAs), Renewable Energy Roadmap (REmap) and Clean Energy Corridors. In addition to Wouters, some of the studies about IRENA focuses on activities such as Global Atlas, REmap, and Project Navigator and evaluate how effective the agency on the activities (Estima et al., 2013; Roesch et al., 2015; Kempener et al., 2015; Sgouridis et al., 2016; Collins et al., 2018).

These studies are the main references for applying social constructivism in international relations to evaluate IRENA’s main activities to encourage global renewable energy policies. For understanding social constructivism, the studies of Onuf (1989, 2013), Wendt (1987, 1992, 1999), Finnmore (1993, 2004), Barnett and Finnemore, (1999); Finnemore and Sikkink (1998), Finnemore and Toope (2001), Baylis et al. (2007) are mainly referred. Social constructivism is used in this study to identify IRENA’s role in

7 creating norms in the international system. There are some studies employed social constructivism to analyse environmental policies such as Blackmore (2013) who uses the theory to examine Germany’s nuclear phasing out policies. Pettenger (2007) also looks at how constructivism changes environmental policies through economic forces, political governance, and international organizations. There are, however, few studies on renewable energy dissemination as a norm by using social constructivism. For example, Yesevi and Yavuz Tiftikçigil (2017) study IRENA using social constructivism, but their studies are specified to Turkey. This thesis therefore attempts to add to our understanding of how social constructivism shapes and nourishes international renewable energy policies.

The first part of the thesis – the introduction- illustrates how and why IRENA has been studied. The second part, discusses the social constructivism in international relations. The third part details the history of international contributions for global renewable energy governance, emphasizing the struggles of the UN and the road to IRENA’s establishment and the fourth part introduces the main goals and strategies of IRENA, as well as its institutional structure and concrete initiatives, in creating and developing global renewable energy policies. Then, in the fifth part IRENA’s activities are evaluated with social constructivism. The final part presents the main findings of the study as well as recommendations for the agency going forward.

8 2. SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIVISM

This chapter consists of two parts, firstly, how social construction is interpreted in international relations studies will be examined, after that, international organizations, which are an essential part of the global structure, and social construction perspective will be mentioned.

2.1. A THEORETICAL OVERVIEW OF SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIVISM

Constructivism was discussed to the field of international relations by Nicholas Onuf in his book World of Our Making as one of the pioneer study, (Onuf, 1989). Constructivism regards human beings as social, and explains that social relations construct people’s attitudes and ideas. People give meaning to the world by speaking and interacting with each other, therefore communication is considered as one of the most influential actions human beings can undertake (Onuf, 2013). “Constructivists focus on the role of ideas, norms, knowledge, culture, and argument in politics” (Finnemore and Sikkink 2001: 393). People and society act in a continuous, mutually reinforcing process. On the one hand, people shape society, and on the other hand, society shapes people.

Onuf emphasizes the two concepts of agents and rules to identify social structure. As main actors, people are the agents in society. The actions of the agents are designed by the requirements and desires of people, and by doing so agents can make their choices in a rational way. Rules offer different options to agents and make the agents active contributors in society. Rules forge a link between people and society. In society, rules guide people about what they should do, and people make preferences among the options to obey or violate the rules. The preferences of people are named as practices and have some outcomes. These rules and unintended outcomes create a structure in society by which this structure affects agents (Onuf, 2013).

Social constructivism is affected from the study of Berger and Luckman (1966), The Social Construction of Reality, which argues that knowledge is shaped in society and ordinary life. Besides knowledge, the identities of people are structured in social discourse. Identities, moreover, can be altered or restructured by relations in society.

9 Advancements of identities for their continuation and creation are realized in a social process, but identities shape social structure at the same time.

Social constructivists are also inspired from Giddens’ (1984) structuration theory, whose analysis duality principle defines the links between structures and human agency. Giddens considers human beings as the main agent in his structuration theory and, according to his theory, agents and their daily practices form structures. On the other hand, agents are restrained by structures as well.

Wendt (1987) argues the agent-structure problem in The Agent-Structure Problem in International Relations Theory, just as Giddens argued before in his structuration theory in a different way. Wendt interprets the duality principle in the field of international relations and contends that states are the main agents and the structure is the international system. Katzenstein (1996) also argues that states are social actors. In addition to the states, Onuf (2013) regards the officers of international organizations as the secondary agents in international system.

Wendt (1999) grounded social constructivism into two main principles. The first principle is that the structures of social actions depend on shared ideas rather than material things. The second principle is that the interest and identities of intentional actors are not given by nature, but constructed by shared ideas. Accordingly, Wendt asserts that international relations consist of social structures. Therefore, constructivists focus on the power, which is more important than its material meaning, and has ideational meaning. The aim of ideational power is not only to control states’ actions, but also create acceptance of ways of thinking and lifestyles (Baylis, et al., 2007). Wendt (1992) argues and emphasizes the difference between social constructivism and rationalist theories. Rationalist theories such as neorealism and neoliberalism assume that states are dominant actors in the international system, and both of them admit that security is directly related to self-interests; however, their understandings differentiate on the idea of relative and absolute gain. According to these rationalist theories, states can change their behaviours upon their gains, but do not alter their identities and interests. On the contrary to rationalists, constructivists argue that the identities of states can change. Because states have various relationships with other states, all of these relations and interactions need to accord with counter identities. As a constructivist,

10 Katzenstein (1996) argues that international relations and domestic factors create changes in states identities and Wendt (1999) accepts that the alteration of identities is difficult but it can be possible with variable actors. States identify themselves as distinct from others, but collective identity is possible with the creation of “we”. States make rational choices to be a part of a group, so it can be said that the constructivist approach on the power differentiates it from neorealism theory, which is based on materialist dynamics as economic and military power within international relations (Risse, 2006). States, particularly powerful ones, require their actions to be legitimate in the international system. With that legitimacy, states can more easily convince other states to cooperate in a group for their actions (Baylis et al., 2007).

The collective identity of a group of states may be achieved on bilateral, multilateral and international levels but all actualize in an anarchic world system. These collective identity efforts also can achieve an institutional feature. According to constructivists, international organizations, as having institutional identities, provide the legalization process with norms with international agreements (Finnemore and Toope, 2001)

A group of international relations scholars, especially realists, believes that international institutions affect the prospects for cooperation on a limited scale because states are strong agents in their own way and their relations are shaped in the anarchic world for their interests Thus, any state cannot rule the others, and there is no institution which is stronger than states in the international system (Grieco, 1988). But it cannot be meant that there is an absence of rules in international relations. If there were no rules, there would be chaos instead of anarchy (Onuf, 2013). Wendt (1999) separates anarchy culture into three types: Hobbesian anarchy based on enmity, Lockean rivalry and Kantian friendship. Anarchic cultures tend to draw the self towards others through violence. Wendt specifically analyses Lockean rivalry rather than the other anarchy cultures. Lockean rivalry accepts that states are the major actors in the international system and give importance to their own benefits in an individualistic manner. States also recognize other states as sovereign and respect their freedom rather than desire to rule over them. International relations, in order words, have common sense despite the individualistic tendencies on states. In rivalry, if a group of states feels danger from the outside, states can cooperate with each other. Locke assumes that states desire security rather than strengthening their power. He states that the pre-condition of membership is

11 based on the individualistic feature of states and their distribution of interests. So, it can be deduced that states can cooperate with each other if they are required for existence. States act both as friends and enemies towards other states in power politics. Wendt put the arguments on the difference between classical realist theory and structural realism. On one side are classical realists as Hobbes, Morgenthau and Niebuhr who believe egoism and power politics are derived from human nature and on the other side are the neo-realists, for instance Waltz, who believe that anarchy is the driving power of war and causes competitive politics. However, Wendt (1992) argues that anarchy is ineffective in distinguishing states’ enemies and friends because the distinction is determined by knowledge and understanding across states. This anarchic system is shaped by the common approach of states that forms the socio-cultural dynamics of the anarchy. As Rumelili (2014) considers that norms, ideas and rules are features of these socio-cultural dynamics and shape states’ behaviour in international politics.

2.2. SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIVIST VIEW ON INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

International regimes are composed of rules and norms. Norms are similar to rules but are differentiated from them by their informality. Norms cannot be considered as a rule until the other agents recognize them (Onuf, 2013). Rules are the main instrument of international system; they guide, suggest and command states as the main actors of international system (Baylis, et al., 2007). Norms also decide the interests of states, which in turn shape states’ behaviour in international politics (Finnemore, 2004). Finnemore and Sikkink (1998) divide norms into domestic, regional and international categories, but every kind of norms is interrelated with each other. Domestic norms influence international norms, and international norms are affected by domestic norms. With given identities, actors accept norms as standardized, suitable behaviours. The acceptability of such behaviours are determined with respect to the judgements of societies.

According to constructivist theory, the diffusion of ideas constructs international structure. In the international system, the transformation of ideas and norms embody a

12 specific change in the system (Finnemore and Sikkink, 1998). International relations are conducted by some informal directive rules. States are seen as equal agents in the theory of international relations, but in reality states are unequal and classified as powerful and weak. At least some rights of states are equal in international politics, when two or more states agree on conventions (e.g., Onuf, 2013). Differently from other international relations theories, constructivists consider the attitudes of international organizations constitutive (Barnett and Finnemore, 1999). Barnett and Finmore (1999) and Wendt (1999) believe that the identities of states are importantly structured by international society. But some constructivists also pay attention to domestic factors in shaping of states’ identities, and domestic systems are regulated by their own laws and norms. On the other hand, the international system has two dominant parameters – the self-interest and coercion of individual states – but the scope of international system is not an influential social structure when we compare with domestic systems. Foreign policies, after all, are mainly shaped by the domestic decisions of states rather than the parameters of the international system (Wendt, 1999). It is obviously seen that international organizations are created by states. However, Barnett and Finnemore (1999) consider that, it does not mean that organizations have no independence. They have own independent policies that influence states.

International organizations have a particular power of enforcement known as the “boomerang pattern”: NGOs influence intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) to alter state policies through changing domestic policies. When NGOs’ demands are rejected by states, they can bypass the states or focus attention on other states through international organizations or directly to intergovernmental organizations to support their norms. Then, the other states or IGOs creates pressure on the refuser state. In the end, refuser states change their policies through the demands of NGOs (Price, 1998). For more than half a century, international policymaking organizations have expanded in developed and developing countries. Finnemore (1993) examines how the ‘teaching’ capability of the international policymaking organizations enhances states’ policies and makes them more amenable and likely to reach their objective. The enhancement in thought of states reflects new norms that are provided by international organizations. According to Barnett and Finnemore (1999: 699), bureaucracies set up rules and develop social knowledge in the process. Bureaucrats, in other words, are pioneers in

13 establishing new norms in the international structure. It is essential that bureaucrats internalize new norms in order to establish international policies. In that point, the bureaucrats close the gap between international organization and states (Finnemore and Sikkink, 1998).

14 3. INTERNATIONAL RENEWABLE ENERGY POLICY CONTRIBUTIONS

This chapter examines the process of establishing international renewable energy governance, and it is divided into two periods as “before IRENA” between 1945-2002 and “road to IRENA” from 2002 to the present.

3.1. BEFORE IRENA (1949-2002)

Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen (2010) divides the attention of the United Nations on renewable energy into three periods: the post-war period from 1945-1973, the post-oil crisis period from 1973-2000, and the transition period after 2000. The relationship between international society and renewable energy dates to the scientific meeting that was organized in 1949. The UN Conference on the Conservation and Utilization of Resources, articulated the limits of the fossil fuels and expressed substantial optimism about the potential to harness wind and solar power to produce electricity (Aull et al., 1950).

International renewable energy corporation continued after 1949. The first international meeting for energy, the United Nations Conference on New Sources of Energy, was held in Rome in 1961, at which prospective studies on wind, solar and geothermal energy technologies were highlighted (UN, 1981: 44). In 1972, the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment was held in Stockholm. The conference ended with a declaration of twenty-six principles, but energy was not given prominence among them (UN, 1972a). Only in the recommendation section energy was mentioned, but renewable energy issues did not receive significant emphasis (UN, 1972b).

The 1973 and 1979 oil crises, though, served as a sort of wake up-call, as it drew attention to the dependency of energy-importing countries on fossil fuels and the devastating effects of high and volatile prices as serious threats to energy-supply security. Meanwhile, global energy demand continued to increase in the late 1970s, and the growing gap between energy supply and demand made renewable energy sources more attractive, particularly to developing countries. In 1981, the United Nations Conference on New and Renewable Sources of Energy was organized in Nairobi, Kenya, where representative of 125 countries discussed the necessity of new renewable

15 energy sources for economic and social development. While the conference seemed to emphasis a goal of increasing renewable energy capacity worldwide, developing countries were the focal point as they had been shown to be so vulnerable to oil price rise and volatility. The Nairobi Programme for Action was prepared for the purposes of making international collaboration, research and development investments, providing financial flows, training services, and empowering local authorities for an energy transition, emphasizing the transfer of technology and financial resources as well as expertise from Northern to Southern countries. Furthermore, developing countries called for establishment of an international organization for renewable energy for surveillance of the conference’s commitments (UN, 1981).

The UN also expressed a need for a global renewable energy institution for renewable energy (UN, 1981), and the Development and Utilization of New and Renewable Sources Committee were established under the UN structure. This committee, however, did not have adequate power to implement its goals. After an attempt to reform its structures and capacities in 1994, it was abandoned altogether four years later (Wright, 2011).

The failure of Nairobi was due, ultimately, to the fact that its commitments were not adequately specific and elaborate and that the oil prices stabilized in the second half of the 1980s and throughout the 1990s. Nonetheless, Nairobi can be considered a turning point for international renewable energy politics (Rowlands, 2005). After that, “Our Common Feature” report of the UN became a central component, as the transition from non-renewables to renewables and energy efficiency was deemed imperative for sustainable development (WCED, 1987).

In the 1990s, international society endeavoured to enhance sustainable development policies for the twenty-first century. In 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), also known as the Earth Summit, was held in Rio de Janerio. Agenda 21 was created to set certain policies for sustainable development, but energy was not included as one of the 21 major topics. It was addressed in different chapters, but not in detail. It did, however, emphasize the goal of increasing renewable energy capacities, especially wind, solar, bio, hydroelectric, in developing countries, in regional and sub-regional energy plans. The reluctance of

16 energy exporters such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait for an energy transition and the relatively stable oil prices in those years caused the stagnation of renewable energy development (United Nations, 1994; Grubb et al. 1993). In the Earth Summit, the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) was founded as well as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) to combat with climate change. After that, the Kyoto Protocol was adopted in 1997 to set binding commitments for developed countries to limit greenhouse gases (GHGs) emissions. Kyoto did not, however, stimulate renewable energy implementation. In the articles of the protocol, renewable energy was rarely mentioned in non-binding clauses. Kyoto was not regarded as catalysing serious efforts to reduce global warming and climate change, thanks largely to the efforts of the United States and fossil fuel-supporting coalitions (Bruce, 2017; Hirschl, 2009).

At the G8 meeting in 2000 in Okinawa, the “Renewable Energy Task Force” was established to strengthen cooperation between G8 members and developing countries to increase renewable energy capacities, but these measures have yet to be implemented. Nevertheless, as was the case after the greater attention of the UN to renewable energy, the efforts of G8 seemed to be an important development (Kirton and Takase, 2002). A year later, as a special session for energy, the Ninth Meeting of the CSD of the UN was held and concluded that the development on national, regional and international renewable energy policies was vital. Most notably, it stated that domestic efforts in both developing and developed countries to improve renewable energy capacities could help increase the share of renewables in total energy mix (UN, 2001).

This long process culminated at the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) organized in Johannesburg in 2002, when energy was declared one of the five main issues. It encouraged the discourse that environmentally friendly energy choices could be promoted in developing countries. The members of the European Union, Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, New Zealand, Tuvalu, and Poland, proposed to set certain targets and schedules for renewable energy. Except for the proponent countries, the Group of 77 members and China, the US, Canada, Australia, and Japan objected to imply certain programmes, prioritizing worldwide access to renewable energy and supporting a more flexible approach (IISD, 2002).

17 3.2. ROAD TO IRENA

Even the divergence between the EU and the other countries became deadlocked, at the end of the Johannesburg Conference, the Renewable Energy Coalition (JREC) were created under the chair of Moroccan Government and European Commission, along with the representatives of 80 countries who attended the meeting. Then German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder invited representatives of the countries for a prospective international renewable energy conference in his country (EC, n.d., Deutsche Welle, 2002). In 2004, Germany held the Bonn Renewable Energy Conference as a continuation of the JREC, and 154 countries were represented as well as scientists, representatives of private sector and nongovernmental organizations. Finance of public and private sector, research and development, policy plans, economic incentives and deployment of renewable energy were pointed out and led to an immediate call for determining individual countries policy frameworks to support renewable energy considering in the context of local barriers or opportunities (Olesen, 2004; Expert Group on Renewable Energy, 2005). The primary result of the Bonn conference was the announcement of the Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century (REN21), a multi-stakeholder network on global renewable energy policies. The conference became a sequence within REN21 called International Renewable Energy Conferences (IRECs) in different countries: in Beijing in 2005; in Washington DC in 2008, in Delhi in 2010, in Abu Dhabi in 2013; in South Africa in 2015, in Mexico in 2017 (REN21, 2018). The Johannesburg conference pioneered the Renewable Energy Conference series and REN21.

The EU has supported renewable energy policies for combating global climate change for many years. Meanwhile, other countries increased their use of renewable energy after the oil price volatility of the period from 2003 to 2006. The fourteenth and fifteenth sessions of CSD identified energy for sustainable development, industry, air pollution, and climate change. The EU contended that the UN remained incapable of developing energy for sustainable development because of ideological and political pressures on the policies of the UN. Russia, Azerbaijan, Saudi Arabia, and the US tried to form an alliance on their energy position. However, the disagreements were seen inside the G77 and China: firstly, oil-importing countries supported the continued

18 domination of fossil fuels; secondly, countries such as Algeria, Egypt, South Africa, and Pakistan were eager to develop nuclear energy technologies; thirdly, the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) favoured renewable energy to combat climate change. There were even major disagreements within the Organization for the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), and AOSIS, G77 and China did not change its policies (IISD, 2007).

On account of the disagreements at WSSD Johannesburg and the CSD sessions, Germany decided that a new renewable energy coalition, independent from the UN, was needed. The structure of this new coalition was driven by the eagerness of individual states instead of the UN-wide consensus system (Roehrkasten and Westphal, 2013). Herman Scheer, who was the Social Democratic Party in Germany (SPD) member of German Federal Parliament, led these efforts and served as president of the European Association for Renewable Energies (EUROSOLAR) and the World Council for Renewable Energy (WCRE). With the aim of widening the scope of EUROSOLAR and creating a new political institution, he prepared the “Memorandum for the Establishment of an International Solar Energy Agency (ISEA)” in 1990 just before the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Jenerio. ISEA was designed in order to reduce the proportion of hydrocarbons and nuclear in the global energy mix, transfer technologic and scientific knowledge from the North to the South, and improve countries’ self-production capacities. The economic gap between the world countries was also considered. Even though it aimed to improve capacity in all countries, developing countries would reach specific support. Thus, membership fees and contributions were arranged in proportion to the GNPs of member countries. Scheer pointed out that for renewable deployment, ISEA would use the same method that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) did to create nuclear as a viable alternative to fossil fuels in the 1950s. Scheer introduced his ideas to the UN General Secretariat Pérez de Cuéllar, and the task force “United Nations Solar Energy Group on Environment and Development” (UNSEGED) was developed. Instead of the German government, the Australian government supported to the memorandum and proposed to the UN to attain the goal setting a special agenda for Rio de Jenerio. UNSEGED then made the recommendation to found ISEA, but the preparatory committee did not approve it (IRENA et al., 2009).

19 Undeterred, Herman Scheer revised the 1990 proposal and prepared the “Memorandum for the Establishment of an International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA)” in 2001, again just one year before Johannesburg WSSD. Different from the first memorandum, the new one suggested that IRENA should be established independent of the UN, but the agency was designed to be open to other related organizations, including the sub-instruments of the UN (Graaf, 2013; IRENA et al., 2009). In the same year as the IRENA memorandum, an introductory conference of EUROSOLAR was organized in Berlin for IRENA. This was viewed as the second venture to achieve its goal, but the circumstances of international society were once again inadequate (Scheer, 2007). In the first four years of SPD and Green Party coalition, from 1998 to 2002, the government developed successful policies on renewable energy inside of the Germany. Then, the coalition was reauthorized for their second electoral period in 2002. Scheer from the SPD and Hans Joseph Fell from the Green Party convinced their ruling coalition to include the establishment of a global renewable energy organization in the new program and extend their ideas to the world, not only to Germany (SPD, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, 2002; see also Roehrkasten and Westphal, 2013). Even the coalition was eager to establish an intergovernmental organization, the Environment Minister Juergen Trittin from the Green Party opposed the idea and he supported to create a nongovernmental organization rather than IRENA (Scheer, 2007). In 2003, the German parliament reached a decision to initiative the launch of IRENA based on Scheer’s proposal (IRENA et al., 2009). After the Bonn Conference and the establishment of REN21, the coalition government led by Schröder did not make further progress because elections were held earlier than expected (Roehrkasten, 2015). These elections, held in 2005, produced a grand coalition between the Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) and the SPD, and Merkel became the new prime minister of Germany who maintained the idea of creation IRENA. The new coalition would be seen as a drawback for the SPD to establish IRENA; however, the SPD gained three major ministries (foreign affairs, development, and environment) that would aid them in accomplish this goal. So, the change of coalition accelerated the creation of IRENA, rather than slowing down it (Roehrkasten and Westphal, 2013).

Finally, the German government took an initiative to establish the new agency in 2007. Merkel’s government wanted to set certain targets together with both countries in

20 Europe and the G8 for deploying renewable energy and combating climate change. The policies were successful in the EU, resulting in a 20% increase in renewable energy capacity and a 20% decrease in GHGs emissions by 2020 (The German Federal Government, 2007; Guardian 2007). At the same time, the UN did not realize gains, and it was understood that the countries could not agree on the certain targets working under the umbrella of the UN. G77 countries had been to grow their interest over time, but countries like Saudi Arabia, which exports hydrocarbon, did not support the targets (IISD, 2007).

The German government nonetheless was eager to disseminate the idea of IRENA to both industrialized and developing countries. Peter Christian Hauswedell, Hans-Ullrich Spohn, and Harald Ganns were entrusted with the task of establishing bilateral relations between IRENA and different countries. Austria and the Czech Republic in Europe; Costa Rica, Chile, Argentina from Latin America; and South Korea in Asia all conveyed further interests to IRENA. First of all, Germany became the leader of the politically powerful countries as well as those most interested in renewable energy. German ambassadors visited the G8 and EU countries, Jordan, United Arab Emirates, and Morocco to support IRENA’s foundation in them. The success of this initiative could be seen in how it drew great interest from countries such as Nigeria and the UAE, which supported the new organization even though they are members of OPEC. Oil import-dependent countries and many African countries also backed IRENA (Scheer, 2008; Roehrkasten and Westphal, 2013). In 2008, IRENA was officially introduced to the world countries (Graaf, 2013).

From 10 to 11 April 2008, the German Federal Government hosted 170 delegates from 60 different countries for the First Preparatory Conference for IRENA. Danish and Spanish representatives strongly supported the conference and convinced countries to become members of IRENA. On the one hand, the Spanish government strongly supported the development of domestic renewable energy capacity. On the other hand, the Danish government endeavoured to make IRENA’s name familiar among the participant countries in Copenhagen Climate Change Conference which was organized in 2009. To overcome the problems related with the rapid growth of energy demand and combat climate change, participant countries expressed their support to establish the agency in the quickest time possible. It was agreed that IRENA must be the first

21 intergovernmental organization for deployment of renewable energy as an independent driving power. In that conference it was claimed that the world would not be able to use renewable energy effectively without a specific intergovernmental organization working on the issue, like IRENA. Furthermore, the prospective activities, aims, organizational structure and financial processes of the organization were discussed in the meeting. The conference chair stated that the agency needs a director-general, a general conference, and a board of governors. The conference concluded with wishes for the new participant countries to take part in the new intergovernmental organization, and the German government invited participants to a founding conference planned for the autumn of 2008 (Roehrkasten and Westphal, 2013; IRENA, 2008a).

After a few months, from 31 June to 1 July at the same year, the German government organized workshops1 for creating IRENA and nearly 100 representatives from 44

countries attended. At the first workshop, a preliminary working schedule and the aims, definitions and actions of IRENA were determined. It was decided that IRENA should provide information on financial opportunities to utilize the investments of their members, rather than being a funding institution directly. Then, at the second workshop, participants discussed the organizational structure, statue, and financial position of IRENA. These two workshops laid the foundation for the future of IRENA.

The second and final preparatory conference was held in Madrid between 24-28 October 2008. Nearly 150 representatives of 51 countries attended. The statue of IRENA was finalized and the signing of the final agreement was set for 26 January 2009 in Bonn. The methods and pre-conditions to choose the interim headquarters and the interim director-general were also settled. For the candidacy of both headquarters and director-general, signatory states were invited to elections hosted by the German government. Also, it was emphasized that IRENA needed to interact with related international institutions to achieve its goals. Madrid marked a new phase, from preparing the organization to operating it (IRENA, 2008b).

1 IRENA (n.d.) Workshops for IRENA. Retrieved 31 July 2018 from

22 By the invitation of Germany, Denmark and Spain, the founding conference of IRENA went ahead as planned in January 2009 in Bonn. All UN members were invited, and 124 countries and the entire European Community attended. There was also considerable interest from non-state organizations such as the UN, regional renewable energy organizations from Europe and the United States, and global non-government organizations (NGOs) like Greenpeace. In total, 47 such organizations were represented at the conference. The German government chaired the conference, while the Danish and Spanish ministers involved in process were elected as vice-chairs. Officers were elected from different countries including Austria, Benin, Chile, Finland, the Republic of Korea, Jordan, and Germany. Delegations from Austria stated their eagerness that the IRENA’s Secretariat be settled in Vienna, while the delegations from the UAE lobbied for it to be in Abu Dhabi. Egypt, meanwhile, requested the opportunity to host the second preparatory conference (IRENA, 2009a). The conference concluded with an agreement to make all efforts to establish IRENA, while a Preparatory Commission would be established to take the essential steps; 75 states from industrialized and developing countries became signatory for creating IRENA (IRENA, 2009b).

According to Roehrkasten and Westphal (2013), 75 signatories was a notable achievement when compared to previous expectation of 50 signatories. At first, neither Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico and South Africa as emerging states nor Canada, Japan, Russia, UK and USA as five members of the G8 did not sign the statue of IRENA. Also seven member states, the Czech Republic, UK, Belgium, Estonia, Hungary, Malta and Slovakia, out of 27 member states of the EU in 2009 also did not sign the founding agreement. Graff (2012) explains that being a founding country posed risk because they might not receive support from the leading global countries and in their regions. Also, 25 of the IEA countries became members of IRENA. Only Canada, Belgium and Hungary did not join the founding agreement, even if they had already demonstrated support for IRENA. Many of the absent countries in the founding process have since been convinced and become members.

The founding members who joined IRENA did so because they believed that the agency would be established in any case and they could have a stronger voice to shape the new organization by being founding members rather than joining later. The US, which was

23 the main promoter of IEA, was reluctant to establish a new international institution at first. But the US government was also aware of the ambition of the European countries to realize IRENA. Thus, the US changed its approach because it wanted to appear sensitive to domestic and foreign public opinion. Additionally, being part of the agency was a reasonable way to give the impression that the Obama Administration (2009-2017) cared about low carbon policies after the Bush Administration’s (2001-2009) pro-fossil fuel policies, and the US became a member in 2011. With the US effect, Australia in 2011, the UK in 2012, Japan in 2014 joined IRENA (Graaf, 2013; Roehrkasten and Westphal, 2013).

Membership in IRENA appeared to help the developing and the least developed countries the most, augmenting their policy-making and technologic capacity. Each member may not have the equal chance to benefit from these features of IRENA, but the limited capacity caused member countries to compete with each other in renewable energy policies and, indeed, it created positive results for the world energy transition. IRENA encouraged developed and emerging countries to deliver their advanced technologies to markets of other countries, even though the agency did not give direct financial support to countries. Also being a member of IRENA helped political leaders who gained from appearing to give importance to the issue of climate change (Upelainen and Graaf, 2015; Graaf, 2013).

Since the beginning, Germany had been eager to establish IRENA’s headquarters in Bonn, but it also wanted to assure the interests and participation of its members. Both for the headquarters and director-general, many countries nominated candidates, which means that German strategy was successful (Roehrkasten and Westphal, 2013). The Second Preparatory Commission was held in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt from 29 to 30 June 2009. For hosting the agency’s interim headquarters, four cities became candidates, Bonn, Vienna, Abu Dhabi, and Copenhagen, although Denmark later withdrew its candidacy. After the brief presentations of the candidates, the UAE became the host country for the interim headquarters. Germany became host Innovation Centre of the agency in Bonn, and Austria planned the Liaison Office in Vienna, which was charged with maintaining relationships between IRENA and UN institutions and other

24 international agencies2. In the meantime, six candidates applied for the interim director-general position. Spain, Norway, Denmark, France, Nigeria and Greece nominated candidates from various areas as ministers, academicians, bureaucrats, and executives of international organizations, although the nominees of Nigeria and Norway were deemed invalid. Hélène Pelosse from France was elected as interim director-general (IRENA, 2009c).

Hosting IRENA was seen as great achievement for the UAE, because Masdar City was the first experience for Arab states to host the headquarters of an international organization. The country was supported by developing countries in Middle East, the Pacific and especially Africa (Weatherby et al., 2018). The achievement can also be explained by the country’s generous financial support for IRENA, 136 million USD over a six-year period for founding its centre, with 50 million additional USD to finance the new projects in developing countries. Germany, on the other hand, could promise only 11 million USD for the centre and 2.5 million USD for development support for renewable energies by 2014 (Speigel, 2009). The UAE’s prominent position in IRENA was supported by many of its Western allies, but many remained suspicious because of the UAE’s massive, decades-long investments in oil. The UAE’s nuclear agreements signed with the US and France for the countries’ electricity needs prompted additional suspicion from renewable energy defenders, as IRENA could become a supporter of nuclear, even the organization has been remained distant to nuclear energy since its creation (Block, n.d.).

The interim director-general of the agency, Pelosse, discussed the nuclear policies of France and the UAE at great length. France was known as the major exporter and user of nuclear energy. The situation put a question mark in the minds of renewable energy defenders about low carbon policies of IRENA. Nuclear could be recognized as low carbon energy by the agency under Pelosse’s administration (Macalister, 2009). As a result, Pelosse was not strongly supported by member countries as director-general (Rhoerkasten and Westphal, 2013).

2 However, the creation of Liasion Office in Vienna was put hold, according to IRENA (2011) in the

25 IRENA’s governance under Pelosse had a rough time until her resignation in October, 2010. Pelosse dissented from the UAE’s authorities. Scheer backed her view that these figures were blocking her efforts within the agency. However, some administrative members expressed that Pelosse was weak on budgetary issues and came out against nuclear energy. Because of her opposition on these critical issues, she was criticized because an international organization cannot get into as sensitive issues. Thus, the US and Japanese governments withdrew their financial supports to IRENA. Pelosse responded by arguing that governments were not serious about the agency and that these attitudes cannot tackle climate change, correct energy injustice among countries, or restrict the use of oil. The voluntary contributions were about 14 million USD, of which only 5 million USD was collected (Emirates247, 2009; New York Times, 2010). According to Wouters (2017), Pelosse took charge of the policymaking process in the European Union, but she was inexperienced operating in the UN system. IRENA’s budgetary system was arranged like the UN, in which member countries give financial support based on their respective gross domestic products (GDP). At the same time, member countries have only one vote each on policy. In practice, the high-level GDP countries want to use their economic power to sway policies in international organizations; otherwise they cut their support. The result of this dynamic was the withdrawal of major countries, such as US and Japan, which created major, obvious obstacles. After Pelosse, Adnan Amin from Kenya was selected as the new interim director-general until the next assembly in 2011. Amin was experienced in the UN system and had already been deputy interim director-general before his assignment in Fourth Preparatory Commission in 25 October, 2010 (Bisiaux, 2010).