In May and June of 2013, an encampment protesting against the privatisation of an historic public space in a commercially vibrant square of Istanbul began as a typical urban social movement for individual rights and freedoms, with no particular political affiliation. Thanks to the brutality of the police and the Turkish Prime Minister’s reactions, the mobilisation soon snowballed into mass opposition to the regime. This volume puts together an excellent collection of field research, qualitative and quantitative data, theoretical approaches and international comparative contributions in order to reveal the significance of the Gezi Protests in Turkish society and contemporary history. It uses a broad spectrum of disciplines, including Political Science, Anthropology, Sociology, Social Psychology, International Relations, and Political Economy.

Isabel David is Assistant Professor at the School of Social and Political

Sciences, Universidade de Lisboa (University of Lisbon) , Portugal. Her research focuses on Turkish politics, Turkey-EU relations and collective action. She is currently working on an article on AKP rule for the Journal of Contemporary European Studies.

Kumru F. Toktamış, PhD, is an Adjunct Associate Professor at the

Depart-ment of Social Sciences and Cultural Studies of Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY. Her research focuses on State Formation, Nationalism, Ethnicity and Collective Action. In 2014, she published a book chapter on ‘Tribes and Democratization/De-Democratization in Libya’.

‘Everywhere Taksim’

Edited by Isabel David and Kumru F. Toktamış

Da

vid a

nd T

ok

tam

ış (

ed

s.)

‘E

ve

ry

w

he

re

T

ak

sim

’

AUP.nl

ISBN: 978-90-8964-807-5 9 7 8 9 0 8 9 6 4 8 0 7 5Sowing the Seeds for a

New Turkey at Gezi

Protest and Social Movements

Recent years have seen an explosion of protest movements around the world, and academic theories are racing to catch up with them. This series aims to further our understanding of the origins, dealings, decisions, and outcomes of social movements by fostering dialogue among many traditions of thought, across European nations and across continents. All theoretical perspectives are welcome. Books in the series typically combine theory with empirical research, dealing with various types of mobilization, from neighborhood groups to revolutions. We especially welcome work that synthesizes or compares different approaches to social movements, such as cultural and structural traditions, micro- and macro-social, economic and ideal, or qualitative and quantitative. Books in the series will be published in English. One goal is to encourage non-native speakers to introduce their work to Anglophone audiences. Another is to maximize accessibility: all books will be available in open access within a year after printed publication.

‘Everywhere Taksim’

Sowing the Seeds for a New Turkey at Gezi

Edited by

Isabel David and Kumru F. Toktamış

gas mask symbolizes the resistance against AKP rule and police brutality amidst media corruption.

Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout

Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press.

isbn 978 90 8964 807 5 e-isbn 978 90 4852 639 0 nur 697

© Isabel David and Kumru F. Toktamış / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher.

Contents

Acknowledgements 11

List of Acronyms 13

Introduction 15

Gezi in Retrospect

Isabel David and Kumru F. Toktamış

Bibliography 25

Section I Gezi Protests and Democratisation

1 Evoking and Invoking Nationhood as Contentious Democratisation 29

Kumru F. Toktamış

2007 – Nation-Evoking Demonstrations 34

Gezi – Summer 2013 37

Conclusion 40

Bibliography 42

2 ‘Everyday I’m Çapulling!’ 45

Global Flows and Local Frictions of Gezi

Jeremy F. Walton

Introduction: Gezi and Rumi’s Elephant in the Dark 45

The Politics of Public Space in Urban Turkey: Taksim Square,

Proscenium of the Nation 46

The Carnivalesque Citizenship of the Çapulcu 50

Gezi and the Discontents of Neoliberal Globalisation 52

Conclusion: Gezi and the Decoupling of Liberalism and

Democracy in Turkey 54

Bibliography 55

3 The Incentives and Actors of Protests in Turkey and

Bosnia-Herzegovina in 2013 59

Ana Dević and Marija Krstić

Introduction 59

Bosnia-Herzegovina 68

Conclusion 72

Bibliography 72

Section II The Political Economy of Protests

4 AKP Rule in the Aftermath of the Gezi Protests 77 From Expanded to Limited Hegemony?

Umut Bozkurt

Understanding the AKP’s Hegemony 79

Neoliberal Populism and the AKP Rule 79 The Explosion of Social Assistance Programmes 81 The Symbolic/Ideological Sources of the Party’s Hegemony 83

The AKP’s Hegemony after the Gezi Protests 84

Conclusion 86

Bibliography 87

5 Rebelling against Neoliberal Populist Regimes 89

Barış Alp Özden and Ahmet Bekmen

Neoliberal Populism, AKP and PT 90

Depoliticising the Question of Poverty 92 Deradicalising Labour 94

Preliminary Reflections on the Protests 97

Bibliography 101

6 Enough is Enough 105

What do the Gezi Protestors Want to Tell Us? A Political Economy Perspective

İlke Civelekoğlu

Re-thinking Neoliberalism in Turkey under AKP Rule 105

Re-thinking the Gezi Park Protests: What did the Protestors

Actually Protest? 111

Conclusion 116

7 ‘We are more than Alliances between Groups’ 121 A Social Psychological Perspective on the Gezi Park Protesters and

Negotiating Levels of Identity

Özden Melis Uluğ and Yasemin Gülsüm Acar

Background to the Gezi Park Protests 121

Social Psychological Perspectives on Collective Action 122 Antecedents to Collective Action 124 Creating a Group from the Crowd 124

‘We Are More than Alliances between Groups’: An

Identity-based Analysis of the Gezi Park Protest Activists 126

Conclusion 132

Bibliography 134

8 Istanbul United 137

Football Fans Entering the ‘Political Field’

Dağhan Irak

Introduction 137

Methodology 139

The Political Context of Turkish Football 141

The Hyper-Commodification of Turkish Football 142

Politicisation of Football Fans in Turkey 144

Fans’ Reasons for Joining the Gezi Protests 146

Discussion 147

Bibliography 150

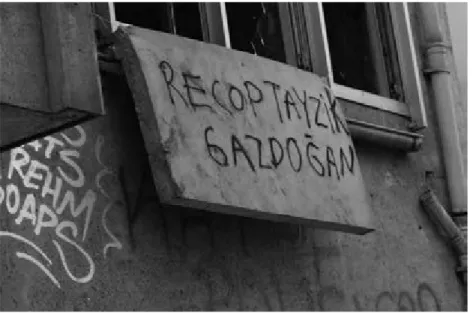

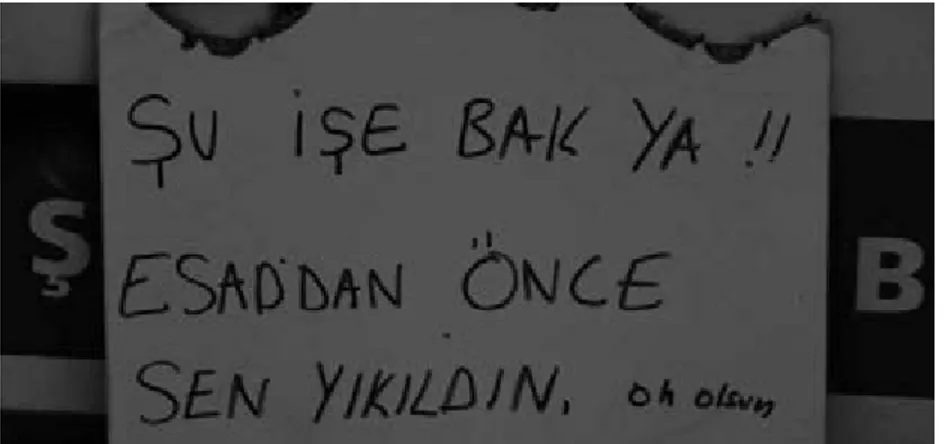

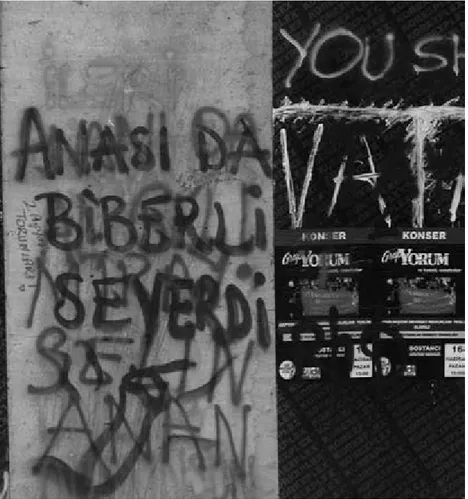

9 Humour as Resistance? 153

A Brief Analysis of the Gezi Park Protest Graffiti

Lerna K. Yanık

Background 153

What is a Graffito? The Features of the Graffiti Collected

around Gezi Park 154

The Role and the Function of Graffiti and Humour: A Short

Conceptual Overview 156

The Graffiti in Gezi Park: Humour or Resistance, or Humour as

Resistance? 158

Delivering Messages through Humour 159

Erdoğan in Graffiti 160 Counterstatement or Intertextual Graffiti 164

Bibliography 182

10 Where did Gezi Come from? 185

Exploring the Links between Youth Political Activism before and during the Gezi Protests

Pınar Gümüş and Volkan Yılmaz

Introduction 185

Social Movement Communities and Social Movement Spillover 186

New Social Movements in Turkey 187

Methodology 188

Five Cross-cutting Themes 189

Aversive Attitude towards Conventional Political Organisations 189 Ability to Organise Horizontally and to Accommodate

Individual Differences 190 Ability to Work with Diverse Political Groups and Cooperate

with Strangers 191

Ability to Transfer Protest Skills 193 The Gezi Protests as a Paradigm-Shifting Event with Respect to the Older Generation’s Perception of the Relationship

between Youth and Politics 194

Conclusion 195

Bibliography 196

Section IV The Politics of Space and Identity at Gezi

11 ‘We May Be Lessees, but the Neighbourhood is Ours’ 201 Gezi Resistances and Spatial Claims

Ahu Karasulu

‘Essentials Are Thus Cast Up’: Space and Contention 203

‘(New Elements) Become Briefly Visible in Luminous

Transparency’: Spatial Claims 206

‘Events Belie Forecasts’: Concluding Remarks 210

Bibliography 212

12 Negotiating Religion at the Gezi Park Protests 215

Emrah Çelik

Introduction 215

The Position of Religious People in the Protests 222

Democratisation vs. Polarisation 225

Conclusion 227

Bibliography 229

13 Gezi Park 231

A Revindication of Public Space

Clara Rivas Alonso

Introduction 231

The Turkish Institutional Approach to Intervention in the

Urban Environment 232

AKP’s Neoliberal Project: Taming the Commons by Taming

the City 233

AKP’s Reliance on the Construction Sector 234 Commodification of Culture and Monopolization of

Narratives: Branding the City 236 Rewriting History 238

Gezi: Mapping the Space Reclaimed and the Victory of the

Commons 239

Gezi Protests as a Reaction against AKP Policies 240 The Value of Resistance in and for a Park: Creating New

Senses of Belonging 240 Responses to the Militarisation of Space: The Return of the

Commons 242

Conclusion 246

Bibliography 247

Section V Gezi in an International Context

14 Gezi Spirit in the Diaspora 251

Diffusion of Turkish Politics to Europe

Bahar Baser

Diffusion of Gezi Spirit to the Transnational Space 252

Creating ‘Gezi Parks’ in Europe 260

Conclusion 264

Protests 267

Beken Saatçioğlu

Introduction 267

The Normative Meaning of Gezi 268

Implications for Turkey-EU Relations 269

Postponing Negotiations on Chapter 22 269 Negotiations on Chapter 22 and beyond 274

Conclusion 279

Bibliography 280

List of Contributors 283

Acknowledgements

This book is the product of an amazing group of people with whom we had the privilege of working.

We would like to express our gratitude to the School of Social and Politi-cal Sciences (Universidade de Lisboa – University of Lisbon), Portugal, and Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, New York, for enabling us to bring together these articles that explore a critical moment in contemporary Turkish history.

We would like to thank the contributors, for all their hard work and patience throughout this process.

We would also like to thank the Amsterdam University Press for accept-ing to publish this book and for their support and diligent work.

We would like to thank Larissa Hertzberg, Nuno Zimas and João Pedro Gonçalves for their precious help with technical issues.

Jim Jasper’s guidance has been invaluable in preparation of this volume. This book is dedicated to the memory of the young people who lost their lives during and in the aftermath of the Taksim/Gezi protests in the summer of 2013.

Isabel David, PhD Kumru F. Toktamış, PhD

List of Acronyms

ADD Association for Ataturkist Thought (Atatürkçü Düşünce Derneği)

AKP Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi)

ALDE Alliance of Liberals and Democrats

BDP Peace and Democracy Party (Barış ve Demokrasi Partisi)

CHP Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi)

DİDF Federation of Democratic Workers’ Organisations (Demokratik İşçi Dernekleri

Federasyonu)

DİSK Confederation of Progressive Trades Unions of Turkey (Türkiye Devrimci İşçi

Sendikaları Konfederasyonu)

EC European Commission

EP European Parliament

EU European Union

GAC EU General Affairs Council

HSYK High Council of Judges and Prosecutors (Hâkimler ve Savcılar Yüksek Kurulu)

IMF International Monetary Fund

İP Workers’ Party (İşçi Partisi)

KESK Confederation of Public Workers’ Union (Kamu Emekçileri Sendikaları

Konfederasyonu)

LGBTI Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex

MEP Member of the European Parliament

MHP Nationalist Movement Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi)

NGO Non-governmental Organisation

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PKK Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Partiya Karkeren Kurdistan)

PT Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party)

SME Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

TGB Youth Union of Turkey (Türkiye Gençlik Birliği)

TKP Communist Party of Turkey (Türkiye Komünist Partisi)

TMMOB Union of Chambers of Turkish Engineers and Architects (Türk Mühendis ve

Mimar Odaları Birliği)

TOKİ Prime Ministry Housing Development Administration of Turkey (Toplu Konut

İdaresi)

UK United Kingdom

Introduction

Gezi in Retrospect

Isabel David and Kumru F. Toktamış

In late May and June of 2013, an encampment protesting the privatisation of the historic Gezi Park, in the public and commercially vibrant Taksim Square, in Istanbul, began as a typical urban social movement for defending individual rights and freedoms and public space, with no particular political affiliation. Thanks to a brutal police response and a brazen reaction by the Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the mobilisation soon snowballed into nationwide anti-government protests (79 out of 81 cities, mobilising 2.5 to 3 million people) (İnsan Hakları Derneği 2013). A coali-tion of the urban, educated, working- and middle classes was crafted with varying social and cultural concerns about both perceived and actual social encroachments as well as the policies of the ruling Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP).

The moderately Islamist AKP party has now been in power for more than a decade and has achieved three national and three local landslide victories in elections since 2002.1 It has reorganized wealth within the capitalist classes while shifting political and social hierarchies of urban populations by rearranging (i.e. simultaneously expanding and limiting) rights and freedoms. It has liberalized the display of religious symbols like headscarves in public spaces such as universities, established non-violent, albeit still patronizing, civic communication channels with minorities such as Kurds and Armenians, all of which have shaken the state-secular elites’ sense of cultural and political dominance. Yet, growing informal and arbitrary control over freedom of the press, occasional limitations on social media outlets such as YouTube and Twitter, non-responsive and evasive actions by government officials at times of public disasters and other social crises have also caused widespread insolence and insubordination among the public. The AKP regime in Turkey has been a paradoxical one with increasing political and social polarisation. This is largely caused by the growing authoritarian and micro-managing attitudes of the prime

1 The percentage of AKP votes was 34.63% in 2002, 41.67% in 2007 and 50% in the 2011 national elections, and 41.67% in 2004, 38.8% in 2007 and 45.5% in the 2014 local elections. See http:// www.genelsecim.org/GenelSecimSonuclari.asp?SY=2002. Accessed 27 May 2014.

minister, galvanizing the sentiments of former elites who had enveloped their lives with the certainties of a Republican regime guarded by the military establishment; an establishment now effectively muzzled.

The Gezi protests and ensuing popular uprisings in many corners of the country may be a threshold, marking a cultural shift away from authoritar-ian forms of political activism in Turkey. The opposition has certainly been shedding its authoritarian uniformity and elite exclusivity and is becoming more democratic, multicultural, and inclusive. The slogan ‘Everywhere Taksim,’ which emerged in the days of the protests, marked the convergence of the rallying point of all demonstrations and uprisings outside Istanbul, signalling the spirit of frustration, resistance and indignation expressed at Gezi Park.

Gezi is a nine-acre urban park built over an ancient Armenian grave-yard and an Ottoman Artillery Barracks in Taksim Square in the heart of Istanbul. Taksim has been a site of student protests and labour mobilisation since the 1960s. During the ‘Bloody Sunday’ of February 1969, demonstra-tors, protesting against the US 6th Fleet’s visit to Istanbul, were attacked by right-wing militia; two were killed and 150 were injured (Ahmad 1977). Taksim has also been the site of 1 May rallies since 1975. The Labour Day Massacre of May 1977 took place there too, when half a million demon-strators were indiscriminately fired upon by unidentified snipers from a municipal building. The official, albeit contested, number of deaths was 34 and the unofficial number of wounded reached 250.2 Since then, there have been occasional peaceful, but often intensely negotiated, May Day rallies at Taksim Square, whenever the authorities grant permission.

A project to construct a shopping centre on this location is among the multiple urban commercialisation and redevelopment projects under-taken by the Metropolitan Istanbul Municipality, controlled by elected pro-Islamic officials since the mayoral tenure of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan between 1994 and 1998. The reorganisation and redevelopment plan for Taksim was initiated in 2009 by the government and in September 2011 the Istanbul Municipality Council, including the members of the opposition parties, unanimously approved the pedestrianisation part of the project, which was partially contracted in 2012. Almost immediately, the project was challenged by the Istanbul Chamber of Architects and the Istanbul Chamber of City Planners (both affiliated to the Union of Chambers of Turkish Engineers and Architects, Türk Mühendis ve Mimar Odaları Birliği, TMMOB), who petitioned courts in May 2012. They were seeking a cessation

of all the projects on the grounds that the plans for commercialisation were inconsistent with the principles of urban planning and violated the regulations of urban historical preservation.3 Consequently, the project was rejected in two separate courts in 2013, just around the time the clashes started. An administrative court stayed the redevelopment plans on 31 May and an appeal to another administrative court upheld this verdict on 6 June.4

These efforts by the professional chamber associations were closely supported by neighbourhood groups, united under the umbrella initiative Taksim Solidarity (Taksim Dayanışması). 2012 had already been a year full of activism for Taksim Solidarity. Prior to 2013, there were at least three large-scale demonstrations organised by the professional chambers and local community organisations, protesting the redevelopment and com-mercialisation projects. At a demonstration in early March, the second largest labour federation in the country, the Confederation of Progressive Trades Unions of Turkey (Türkiye Devrimci İşçi Sendikaları Konfederasyonu, DİSK), joined forces with the professional chambers and local community organisations as the union president declared the symbolic and historical significance of this particular urban square for the labour and socialist movement. He suggested that Prime Minister Erdoğan was acting like an Ot-toman Sultan and ignoring the opposition.5 At the same protest, representa-tives of the Taksim Solidarity movement were determined to prevent a fait accompli, defining the renewal project as the elimination of human beings, the erection of concrete structures and the loss of the square’s authenticity.6 As the official bidding process to identify and appoint the contractors started, a second large-scale demonstration was called in late June of 2012. During an uneventful summer, the parties continued their court battles and by October 2012, some cafes on the square started receiving their evic-tion papers. The coalievic-tion of groups resisting the project started petievic-tion campaigns and called for another mass demonstration on 14 October. By early November, members of coalition groups were taking turns to ‘guard the park’ as the preparations for construction were underway.

As the construction work was starting in January 2013, Taksim Solidarity, together with the students of the Faculty of Architecture of Istanbul Techni-cal University, Techni-called for common breakfasts at the park every Sunday,

3 http://www.mimarist.org/2012-08-13-16-09-05.html.

4 http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/gundem/23644273.asp. See also http://www.radikal.com.tr/ turkiye/gezi_parki_raporu_dokunamazsiniz-1135658.

5 http://www.etha.com.tr/Haber/2012/03/03/guncel/taksim-ayaklarin-bas-oldugu-yerdir/. 6 http://www.etha.com.tr/Haber/2012/03/03/guncel/taksim-ayaklarin-bas-oldugu-yerdir/.

starting on 26 January. They initiated another large-scale demonstration with the professional chambers on 15 February. A neighbourhood organisa-tion called the Associaorganisa-tion for the Protecorganisa-tion and Improvement of Taksim was officially created in March, collecting more than 80,000 signatures against the development and organising a music and dance festival on 14 April, which was attended by hundreds of citizens and a few officials of the main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, CHP). By May 2013, Taksim Solidarity was still organising vigils at the park every Saturday between 3 pm and 6 pm.7 By 27 May, when police forces started to evacuate the park, hundreds of civic organisations were already in coordination, using social media to make public calls for the space to be defended.

The brutal eviction of around fifty young people occupying the park to save approximately 600 trees in late May turned into nationwide protests and clashes throughout the month of June, exacerbated by the excessive use of police force against peaceful demonstrators. Gezi was re-opened to the public on 1 June and immediately re-occupied by an increasing number of groups from all walks of life; thousands of people marched, some displaying Turkish flags. Taking the streets and even the bridges, denizens of Istanbul reached out to Gezi from different districts of the city, throughout the night, determined to support and shelter young people from further police brutal-ity. The popularity of the occupiers among the city dwellers became clear with the march of more than 10,000 football fans, in an uncharacteristic display of fraternity on 8 June.

For almost two weeks, the park turned into a forum for public festivities with makeshift libraries, kitchens, seminars, concerts, classes from maths to yoga, as well as ongoing clashes with the police force, as the world’s attention turned to Istanbul and other cities in Turkey where demonstrators expressed support for the Gezi protestors and vocalized a wide scope of grievances, ranging from freedom of expression to defence of state secularist principles. Forums developed in several cities. These public forums have now become a constitutive part of localized protests and negotiations, mostly related to issues of neighbourhood redevelopment and democratic participation.

7 Interviews with Taksim Solidarity representatives. For the vigils, see http://www.sendika. org/2012/11/taksim-nobeti-gunlugu-taksim-dayanismasi/.

In early June, Prime Minister Erdoğan dismissed the protestors in his now famous ‘a few çapulcus’ speech.8 This labelling of the protesters as ‘looters’ was immediately re-appropriated by the protesters with an irreverent twist and developed into an anglicized neologism, ‘chapulling,’ loosely referring to ‘fighting for one’s rights.’ Penguins were to constitute another symbol of resistance, irreverence and cognitive disconnect of the media eager to support the government, when CNN Türk chose to air a documentary on the lives of these polar birds instead of broadcasting the protests.

The two weeks of encampment at Gezi Park was a fresh yet exhilarating moment in Turkey’s political history. During the intensification of these political confrontations, the government’s responses to the protests were not uniform. Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç, who had categorically denied the protestors’ list of demands, apologised for the ‘excessive use of police force’ on 4 June.9 President Abdullah Gül, who had called for modera-tion in early June, also took it upon himself to announce the suspension of the redevelopment plans in mid-July.10 Throughout this period, the prime minister was the only political figure who was unwavering in his defence of the redevelopment project and condemnation of the protests as conspiracies against his rule. His supporters staged a midnight welcoming demonstration upon his return from a North African visit on 7 June, asking for his permission ‘to crash Gezi.’11 Banking on a form of majoritarianism that has replaced any democratic treatment of his opposition, Erdoğan insinuated that 50 per cent of the population in Turkey was ready to attack and destroy ‘Everywhere Taksim’ protests across the country. Following a series of impatient and brusque warnings to end the protests and the encampments, the prime minister held a meeting with the representatives of the protestors during the early hours of 14 June, during which he declared that the future of the project would be decided by a referendum.12 At his subsequent counter rallies in Ankara and Istanbul on 15 and 16 June, he reiterated his support for the redevelopment project and called for ‘respect

8 http://haber.sol.org.tr/devlet-ve-siyaset/erdogan-onbinleri-birkac-capulcu-ilan-etti-diktatorluk-kanimda-yok-dedi-haberi-739. 9 http://www.aljazeera.com/news/europe/2013/06/20136551212442132.html. 10 http://gundem.milliyet.com.tr/gezi-parki-projesi-askiya-alindi/gundem/ydetay/1724812/ default.htm. 11 http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkish-pm-erdogan-calls-for-immediate-end-to-gezi-park-protests-.aspx?PageID=238&NID=48381&NewsCatID=338. 12 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-22898228.

for the national will,’13 while addressing his 300,000 supporters and as the police operation to ‘clean’ Taksim Square was heading towards its most brutal phase.

In sum, ‘Everywhere Taksim’ was more than an environmental resistance located in one urban park; it was a series of popular uprisings and demon-strations throughout Turkey, particularly between 31 May and 25 June, with participants from a wide array of social groups: Alevis, religious people, Kurds, women, Christians, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI), Kemalists and football fans. The peaceful co-existence between these very diverse and, until then, antagonistic groups demonstrates that something greater happened at Gezi: the creation of a spirit of tolerance that may well sow the seeds for a new Turkey.

The Turkish Medical Association announced that more than 10,000 people were wounded, some critically, during the six weeks of protests.14 According to the Istanbul Bar Association, more than 900 people were detained in Istanbul alone during the first few weeks.15 As a result of exces-sive police force used against unarmed demonstrators eleven people lost their lives, including one policeman in Adana and at least three possible bystanders. Notably, many of the young men, between the ages of 15 and 26, who were killed by police attacks were Alevis (a progressive religious sect that has been politically and culturally marginalized by the AKP regime). The first fatality was Ethem Sarısülük (26), in Ankara on 1 June, later followed by Mehmet Ayvalıtaş (20) in Istanbul, Abdullah Cömert (22) in Antakya, Medeni Yıldırım (18) in Diyarbakır, Ali İsmail Korkmaz (19) in Eskişehir and, most recently, Berkin Elvan (15) in Istanbul, who died after nine months in a coma. In September 2013, Ahmet Atakan also died during a follow-up protest in Antakya.

This volume has two goals: to make sense of the significance of the Gezi protests and to contribute to the literature on social movements in Turkey. It will be contended that Gezi represents a major landmark in Turkey, for a number of reasons. Firstly, the Gezi protests showed the world the authori-tarian nature of the ruling AKP, shredding the image it had constructed as a liberal democratic party, one that would be capable of acting as a model of reconciliation between Islam and democracy. The protests further proved

13 http://siyaset.milliyet.com.tr/ak-partililer-kazlicesme-ye-akin/siyaset/detay/1723747/ default.htm.

14 http://www.ttb.org.tr/index.php/gezidirenisi.html.

15 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jun/20/turkey-divided-erdogan-protests- crackdown.

that democratisation in Turkey still has a long way to go. Secondly, Gezi acted as a trigger for the repoliticisation of Turkish society and especially of younger generations, until then considered apathetic. Thirdly, the Gezi protests constitute evidence of a major sociological change in Turkish soci-ety, for they provided the first platform for the unification of antagonistic groups, such as LGBTI, Islamists, headscarved women, Kemalists, feminists, Alevis and Kurds. Thus, Gezi was a turning point for overcoming Turkey’s deep cleavages. A fourth argument advanced in this volume is that Gezi constituted a branch of the wider global resistance and protest movements that have swept the globe of late.

For this purpose, the volume bridges a collection of field research, qualitative and quantitative data, theoretical approaches and transna-tional comparative contributions. The analyses include a broad spectrum of disciplines, including Political Science, Anthropology, Sociology, Social Psychology, International Relations and Political Economy. With its in-terdisciplinary content and approaches, the volume provides a solid base for historical, local, global and regional comparative analyses. The essays reflect the multidimensional qualities of social movements and provide grounds for further research about Turkish society as well as about the Middle East and Europe.

The contributions to this volume are structured around five broad themes, which try to encompass the main focal points of the protests. Section I addresses the issue of how AKP’s rule failed to deliver on the expectations of liberalisation and democratisation in its eleven years of power. These acted as the perceived triggers for the Gezi protests. Section II looks at the neoliberal reforms enacted by the party and how the AKP has sought to consolidate its hegemony through them. At the same time, however, these reforms have alienated and excluded a substantial portion of the population from the benefits of capitalism. Section III deals with protestors and repertoires of protest: in a civil society seen as apathetic, the protests surprised, not only because they brought together completely different and, sometimes, antagonistic sections of the Turkish popula-tion, but also for their creativity. Section IV considers the issue of public spaces as loci of contention; it further contends that space is constitutive of identity. Finally, Section V refers to the reverberation of the protests in the international sphere.

The volume opens with Kumru F. Toktamış’s enlightening comparison between the two major mass mobilisations against the AKP government: the 2007 protests and the Gezi protests. Through this comparison, the author uncovers the shifting patterns of nationhood in Turkey: from a

top-down approach, prevalent in the 2007 Republican demonstrations, to a multiculturalist one, unveiled by the Gezi protests. Following this idea, and building on discursive and relational approaches from Charles Tilly and Rogers Brubaker, Toktamış contends that despite the party’s growing authoritarian tendencies, the AKP period may be seen as one of the most vibrant in the history of Turkish democracy, given the increasing political involvement of people from all walks of life.

Jeremy F. Walton’s chapter engages in a mediation between the narratives of the proponents and the opponents of the protests by focusing on the figure of the çapulcu, which ultimately created a common identity out of heterogeneous groups. In order to do so, Walton combines three elements that can be identified in the Gezi protests: the politicisation of urban space, with an emphasis on Taksim square; the Bakhtinian concept of ‘carnival’; and the inclusion of the Gezi protests as a branch of the global protest movement across the globe.

Ana Dević’s and Marija Krstić’s chapter presents an insightful compari-son of the protests in Turkey and Bosnia-Herzegovina. The authors focus on elite behaviour in both countries and the failed promises and expectations regarding democratisation and social and economic improvements as the source of protests. To this end, Dević and Krstić conducted field research by interviewing Gezi activists on their perception of measures pertaining to democracy and fundamental rights and freedoms enacted by the AKP. The authors analyse the similar nature of the profile of protestors in both countries, identifying them as the elements excluded from the dominant political system.

Umut Bozkurt’s chapter focuses on the interplay between the factors that explain AKP’s hegemony and the impact of the Gezi protests on this hegemony. To this end, the author makes use of the concept of ‘neoliberal populism,’ interpreted in a Gramscian fashion. This hegemony has been secured, Bozkurt argues, not only through neoliberal economic policies that favour the interests of the economic bourgeoisie, but also through the use of symbolic and religious codes such as Sunni Islam, conservatism and nationalism. The author contends that, as a result of the Gezi protests, the AKP’s previously expansive hegemony has been transformed into a limited hegemony.

Barış Alp Özden’s and Ahmet Bekmen’s contribution presents an impor-tant comparison of the protests that occurred in Turkey and Brazil, given the similarities behind their motivations and in terms of the social composition of the demonstrators. They explore how the dominant neoliberal populist practice in both countries depoliticizes structural social problems, creates

non-class forms of identity and representation, and thus attempts to defuse social conflict. Özden and Bekmen contend that, ultimately, neoliberal regimes are creating a class consciousness among the labouring classes that might trigger the formation of an alternative hegemonic bloc.

İlke Civelekoğlu’s chapter argues for a political economy-based explana-tion of the reasons behind the Gezi protests. Drawing from Karl Polanyi, the author argues that Gezi demonstrators took to the streets in order to resist the commercialisation of land as well as the commodification of labour brought about by neoliberal policies. Civelekoğlu then engages in a discus-sion about whether the protestors can be seen as a societal countermove-ment, aiming to halt market expansion with the goal of protecting society. In this respect, the author discusses the implications and the outcomes of the protests for Turkish democracy.

Özden Melis Uluğ and Yasemin Gülsüm Acar offer a social psychological perspective on the Gezi Park protesters by focusing on social identity theory as an underlying explicative tool for collective action. The authors contend that the defining moment for the creation of a shared identity was the inter-nalisation of the word çapulcu. The authors conducted a series of interviews with activists participating in the protests in different cities across Turkey. As a result of their diversity (including Alevis, Anti-capitalist Muslims, Revolutionary Muslims, members of the football fan group Çarşı, women’s rights activists, Kemalists, Kurdish activists, LGBTI activists, trades union members, members of the Communist Party of Turkey [Türkiye Komünist Partisi, TKP] and Ülkücüler), these valuable interviews allow the reader to perceive the variegated reasons behind the protests. They also bring to the fore a number of shared perceptions that helped unite these often opposing/ clashing segments of Turkish society.

Dağhan Irak’s chapter offers a ground-breaking view of one of Gezi’s most visible actors – the football fans. The author explains how football fandom became increasingly politicised by the growing commodification of the sport and rising AKP interference in football regulations and in fans’ lifestyles. These changes, Irak argues, allowed for the creation of a common ground between Istanbul’s major football fans, until then divided by micro-nationalisms. In this respect, and using the Bourdesian concept of ‘cultural capital,’ the Gezi protests may eventually be seen as a springboard for the creation of a fan-based political supra-entity. The chapter thus paves the way for further study on the effects of commodification processes and precariousness on the growing politicisation of sports fans.

Lerna K. Yanık provides another innovative approach to the Gezi protests through the lens of visual humour, laying the foundations for a research

agenda on graffiti and political humour in Turkey. In order to do so, the author photographed and conducted an analysis of graffiti written during the June 2013 events and how these were used to challenge authority. Ad-ditionally, the chapter operates as a valuable tool for the memorialisation of the forms of protest that took place, as all of the graffiti have been erased from the streets of Istanbul.

Volkan Yılmaz’s and Pınar Gümüş’s chapter brings yet another invaluable contribution to the study of the Gezi protests. The authors deconstruct the conventional idea that the Turkish youth was apolitical and further explain how this newly politicised youth was highly influential in the development of the protests. Namely, Yılmaz and Gümüş demonstrate how young people, as members of already existing social movements, transferred their organi-sational features, their political discourses and their forms of creating and sustaining solidarity networks to the Gezi protests. The authors’ findings are supported by field research conducted before and after Gezi.

Ahu Karasulu’s chapter analyses the acts of continued resistance that began with Gezi under the theoretical framework of Doug McAdam, Charles Tilly and Sidney Tarrow’s Dynamics of Contention, with an emphasis on the spatial dimension of claims. The author contends, in a dialectical fashion, that contention is not only affected by space but also that it produces space. The fact that space symbolises power must be seen as the key to understanding Taksim Square, which is the symbol of both the Republic and secularism. In trying to close the Square or gentrify it, the government displays power and tries to depoliticise this particular space. Thus, Taksim becomes a symbol of resistance for those who oppose government policies. Emrah Çelik discusses the role of religion in the protests. Through a series of in-depth interviews with secularist demonstrators and activists, the author shows how one of the main concerns was government interference in lifestyles and not opposition to religion as such. The interviews with religious elements at the park, on the other hand, offer valuable insights into the rejection of what is perceived as the anti-religious capitalism promoted by the AKP. One of Çelik’s main findings is the growing acceptance of religion by secularists, especially among the younger generations, and how Gezi helped cement that spirit of tolerance, in a major sociological shift in Turkish society.

Clara Rivas Alonso’s chapter demonstrates how the protests were fuelled by the AKP policy on urban construction, a pillar of Turkish economic growth, establishing a direct link between urban exclusion and social unrest. The author focuses on the events at Gezi through the prism of the occupation of the public spaces as an exercise of social participation,

grassroots alliances and identity construction. In order to better understand how space is constitutive of identity, the author brings to public knowledge invaluable maps of space occupation by the different groups in the so-called Gezi Republic. Seen as a mahalle (‘neighbourhood’), Gezi Park provided a ‘sphere of possibility’ – a space of solidarity and tolerance.

Bahar Baser provides yet another ground-breaking study on the way the Gezi spirit was perceived and picked up by the Turkish and Kurdish diasporas in Sweden, Germany, France and the Netherlands. Based on fieldwork observation and semi-structured interviews, the author explains the role of the diasporas in both denouncing the violent repression of the protests and clarifying their goals in their hostlands. Baser concludes that these acts of solidarity constituted a branch of home events and, as in Turkey, diaspora protests created a sense of fraternity among previously opposing groups.

Beken Saatçioğlu’s chapter concludes the volume with a ground-breaking chapter on the implications of the events at Gezi for Turkey’s European Union (EU) accession process. Given that the EU has perceived Gezi as evidence of the AKP straying from democratic standards, the author con-tends that EU-Turkey relations will, from now on, be guided mainly by normative considerations, and not, as before, by intergovernmental or rationalist ones. Saatçioğlu observes a two-fold behaviour emerging from these relations between the parties: on the one hand, Turkey’s compliance with democratic norms can be used by the EU to veto, postpone or suspend accession negotiations; on the other, the Union will keep the negotiations open as a policy instrument in order to promote democratisation.

Bibliography

Ahmad, Feroz. 1977. The Turkish Experiment in Democracy, 1950-1975. London: Westview Press. Bila, Fikret. 2013. ‘Cumhurbaşkanı Abdullah Gül Çankaya’da verdiği resepsiyonda konuştu: Gezi

Parkı Projesi Askıya Alındı.’ Gündem, 19 June. http://gundem.milliyet.com.tr/gezi-parki-projesi-askiya-alindi/gundem/ydetay/1724812/default.htm.

Dağlar, Ali. 2013. ‘Mahkeme Topçu Kışlası’nı iptal etmiş.’ Hurriyet, 4 July. http://www.hurriyet. com.tr/gundem/23644273.asp.

Erbil, Ömer. 2013. ‘Gezi Parkı Raporu: Dokunamazsınız.’ Radikal, 31 May. http://www.radikal. com.tr/turkiye/gezi_parki_raporu_dokunamazsiniz-1135658.

‘Erdoğan onbinleri “birkaç çapulcu” ilan etti, “diktatörlük kanımda yok” dedi.’ Sol, 2 June 2013. http://haber.sol.org.tr/devlet-ve-siyaset/ erdogan-onbinleri-birkac-capulcu-ilan-etti-diktatorluk-kanimda-yok-dedi-haberi-739. ‘Erdoğan Kazlıçeşme mitinginde Konuştu!’ Milliyet, 16 June 2013. http://siyaset.milliyet.com.tr/

‘Gezi Direnişi Sürecinde Türk Tabibler Birliği.’ Türk Tabipleri Birliği. http://www.ttb.org.tr/ index.php/gezidirenisi.html. Accessed 5 June 2014.

İnsan Hakları Derneği. 2013. ‘Gezi Parkı Direnişi ve Sonrasında Yaşananlara İlışkın Değerlendirme Raporu.’ Ankara: İnsan Hakları Derneği.

‘Taksim ayakların baş olduğu yerdir.’ EHA, 3 March 2012. http://www.etha.com.tr/ Haber/2012/03/03/guncel/taksim-ayaklarin-bas-oldugu-yerdir/.

‘Taksim Dayanışma Güncesi.’ TMMOB Mimar Odası, 26 August 2013. http://www.mimarist. org/2012-08-13-16-09-05.html.

‘Taksim nöbeti günlüğü – Taksim Dayanışması.’ Sendika, 8 November 2012. http://www.sendika. org/2012/11/taksim-nobeti-gunlugu-taksim-dayanismasi/.

Traynor, Ian and Constanze Letsch. 2013. ‘Turkey divided more than ever by Erdoğan’s Gezi Park crackdown.’ Guardian, 20 June. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jun/20/ turkey-divided-erdogan-protests-crackdown.

‘Turkey Protests Continue Despite Apology.’ Al Jazeera, 6 June 2013. http://www.aljazeera.com/ news/europe/2013/06/20136551212442132.html.

‘Turkey Protests: Erdoğan Meets Gezi Park Activists.’ BBC, 14 June 2013. http://www.bbc.co.uk/ news/world-europe-22898228.

‘Turkish PM Erdoğan Calls for “Immediate End” to Gezi Park Protests.’ Hürriyet Daily News, 7 June 2013. http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkish-pm-erdogan-calls-for-immediate-end-to-gezi-park-protests-.aspx?PageID=238&NID=48381&NewsCatID=338.

‘30 yıl sonra kanlı 1 Mayıs - Ertuğrul Mavioğlu (Radikal).’ Sendika, 29 May 2007. http://www. sendika.org/2007/04/30-yil-sonra-kanli-1-mayis-ertugrul-mavioglu-radikal/.

1 Evoking and Invoking Nationhood as

Contentious Democratisation

Kumru F. Toktamış

The Gezi protests and the 2007 Flag/Republic demonstrations constitute the two major episodes of mass mobilisations against the AKP. A comparative analysis of the organisation, participation, claims and immediate responses of both episodes is critical for demonstrating the changing popular dis-course of nationhood and citizenship, and indicates a democratic shift in the public definitions of these concepts. With massive historical protests in place, from a Contentious Politics approach to democratisation,1 the AKP decade might, paradoxically, be one of the most democratic periods in Turkish history; not necessarily due to the actions and policies of the party, but to the extent of increasing participation and political engagement of the population from different walks of life.

Since both waves were clearly critical of and targeting the AKP regime, and neither was centred on addressing the economic policies of the party, during both cycles of mobilisations participants voiced definitions of their collectivities as they envisioned citizenship, democratic participation and nationhood. The most significant shift is from a monolithic sense of top-down engineered nationhood to a multiculturalist sense of citizenship. These shifting patterns and multiple meanings of nationhood indicate an ongoing dialogical contestation, negotiations regarding the criteria of what constitutes Turkishness and what qualifies as the Turkish nation.

A survey of organising bodies and slogans as dialogical contestations indicate that the self-definitions of anti-AKP demonstrators radically changed between 2007 and 2013, and such change can be explained by the paradoxical processes of democracy that were in action during the AKP government. A process-oriented, relational and dialogical analysis of these

1 Contentious Politics, as coined by Tilly, Tarrow and McAdam (2001, 5), among others, refers to collective political struggles that take the form of disruptive – rather than continuous – public claim-makings outside ‘regularly scheduled events such as votes, parliamentary elections and associational meetings’ and ‘well-bounded organizations, including churches and firms.’ This approach is significantly more dynamic than classical social movement studies, which often focus on structures and individual movements and ignore the interactive processes of claim-making among the actors.

two episodes of protests indicates an expanded and broadened popular opposition despite possible and imminent reversals of de-democratisation.

The theoretical premises of this essay in terms of democratisation, na-tionhood and dialogical analysis are eclectic yet complimentary. First, it is based on an understanding that democracy is not a thing to be developed by democratically-minded actors (Tilly 2007 and 2009). Similarly, no nation is to be understood as a given entity, but rather as a historical product of evoking and invoking a sense of nationhood and shifting identities of membership to a politically sanctioned institutionalized community.2 Finally, discourse is understood not merely as reflective but as a central and crucial constitutive component of mobilisations in the form of interactive repertoires of meanings that could be captured dialogically as contenders challenge authorities and express their claims (Steinberg 1999). All these theoretical debates understand democracy, nationhood and citizenship in a process-oriented and relational perspective, within which discourse constrains and confines the ways in which material conditions of social life become intelligible to the participants and acted upon by agents of social change. Centrality of discursive and interactive meaning in nation-hood compels us to look at the claims articulated by the protesters and the contested qualities of nationhood call for an understanding of democracy as a process.

Following Charles Tilly’s argument that democracy is not a designed institution, but rather a product of contestation among actors who may or may not be democratically-minded social and political agents, this article argues that the shifting claims and repertoires of the anti-AKP mobilisations reveal a paradoxical process of overall democratisation dur-ing an increasdur-ingly authoritarian rule by the party. Based on a historical understanding that ‘democratization […] never happened without intense contention’ (McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly 2001, 272.) this unique concep-tualisation follows the definitions of democracy as the processes during which previously excluded populations participate in political decision making (Schwartz 2009), as contestation (Dahl 1971) and as how opposition is treated (Przeworksi 1991). Envisioning democratisation as a process of expanding, broadening and protected participation of populations, and de-democratisation as the process during which certain groups’ access to

2 For Brubaker (2005, 116), ‘nationhood is not an ethnodemographic or ethnocultural fact; it is a political claim. It is a claim on people’s loyalty, on their attention, on their solidarity. If we understand nationhood not as fact but as claim, then we can see that “nation” is not a purely analytical category.’

political decision-making is limited, unprotected and unequal, provides a powerful analytical framework to capture the many paradoxical predica-ments of the AKP regime.3

According to the Contentious Politics perspective, ‘democracy results from, mobilizes and reshapes popular contention’ (McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly 2001, 269) and democratisation and de-democratisation are defined within a contingent continuum where a regime moves ‘toward or away from relatively broad, equal and protected binding consultations of the govern-ment’s subjects with respect to governmental resources, personnel, and policies’ (Tilly and Tarrow 2007, 216). In this process-oriented understanding of popular participation, democracy is not a ‘thing’ to be built, but is the product of mobilisations and clashes between the state and its challeng-ers. Moreover, it is not the motives, interest, intentions and policies of the actors that shape a democratic regime, but the contradictions, clashes and contentions among the actors that open spaces for democratic participation. As stated by Tilly (2009), democracy flourishes ‘on bargained compliance, rather than on either passive acceptance or uncompromising resistance’. Democracy is not a switch that can be turned on or off, nor is it a product of actions of elite experts or advocates of democratic action; democracy is more like a thermometer that operates in degrees. According to Tilly, every time rulers intervene in non-state resources, activities or interpersonal con-nections, they encounter resistance, negotiation or bargaining from those who are ruled. The degrees of the thermometer shift as the ways in which rulers organise themselves end in continuous negotiations between the rulers and the ruled over how (social) resources are acquired and allocated.

Democratisation ‘is not a finite and linear process and [...] various forms and processes of contention […] can combine to produce’ democratic prac-tices as well as detours, ‘not only because some people oppose democracy itself, but also – and probably primarily – because claims made in the name of democracy threaten their vested interests’ (McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly 2001, 268).

According to the Contentious Politics approach, public actions and demonstrations, such as the Gezi Protests – and even the 2007 Flag dem-onstrations –, are by definition democratic because individuals and groups transform themselves into agents of change with immediate and long-term impact on the government policies and actions, thus affecting state-society

3 Such conceptualisation is also disassociated and distinctive from substantive (how much a regime makes people happy, like UN charts), constitutional (legal/formal structures), procedural (elections, etc), ideal (normative) understandings of democracy (Tilly 2007, 7).

relationships. This relationship does not necessarily follow a gradualist evolution towards more institutionalisation of democracy, but is contingent on the processes and mechanisms of the contestation on the grounds that shape the nature, quality and extent of participation by citizens.

Nationhood is not an entity with essentialist properties. Nationhood, as argued by Brubaker, is also a contested ground of collective self-understanding of the polity. According to this self-understanding, nationhood and citizenship are not only legal and political designations, they are also cultural constructs that are created, supported, maintained and challenged by contending actors. Following Brubaker’s argument that nation is a cat-egory of practice and not analysis, nationalism is always to be understood as an interactive product and nationhood as relational. Brubaker’s work highlights the ‘cultural idioms of nationhood’ that express and constitute in-terests and identity. In other words, a nation is not a group with substantive and essential properties but ‘nationalisation’ is a ‘political, social, cultural and psychological process’ and nationhood is a groupness ‘as a contextually fluctuating conceptual variable’ (Brubaker 2004, 54).

Collective actions and mobilisations are always resourceful fields reveal-ing a sense of belongreveal-ingness and the self-identification of the participants. Since identity is never private or individual and always public and relational, and because its deeply interactive character can be exposed in ‘constantly negotiated conversations rather than individual minds,’ mobilisations often constitute a good source of capturing the otherwise fluid definitions of ‘us’ and ‘them.’ Publicly stated contentious ideas of nationhood feed back into the social and political (contentious) relations where new changes take place. The anti-AKP demonstrations of 2007 and 2013, with clearly expressed and challenged ‘cultural idioms of nationhood,’ are the ‘contingent events’ that have ‘their transformative consequences,’ which has constituted the dynamics of nationhood.

Finally, the dialogical component of the shifting discourses of nationhood and citizenship can also be captured within the analytical framework of Contentious Politics. Following Mark Steinberg, who crafted the term ‘reper-toires of discourse,’ based on Tilly’s formulation of ‘reper‘reper-toires of collective action,’4 collective identities such as nationhood and citizenship are formed interactively, in a dialogical manner, and they are bound by the ways in which contestants articulate their claims. According to Steinberg, all social

4 According to Tilly (1995) ‘repertoires of collective action’ are products of processes of group interaction among multiple contesting parties in a conflict; they are bound and shaped by the context of the contention and constituted of shared routines for collective use.

mobilisations involve discursive contestations when protesters challenge the voice of authority by questioning their interpretation of its meanings. In doing so, they do not come up with a wholesale shift in the meaning, but ‘pragmatically engage in appropriation as they find its elements become more transparently vulnerable to questioning and transformation within a specific context. Through this process challengers construct the fighting words essential to […] collective action’ (Steinberg 1999, 17).

Dialogical meaning construction posits that ‘all challenging groups are deeply engaged in the process of creating a collective identity, which legitimizes their grievances and claims and provides license for action.’ They fashion their collective identities dialogically, developing ‘discursive repertoires from the friction of conflict’ (Steinberg 1999, 20-21). Drawing heavily on Bakthin’s idea of dialogical struggle, Steinberg’s (Ibid., 17) work illustrates how

subordinate groups seek to subvert the power-holders’ authoritative voice, first by questioning the accepted interpretations of dominant meanings, [then] when challengers expose these as defined in the interests of power, they can attempt to appropriate and transform the genres into fighting words, which broadcast their shared sense of injustice and resolution.

As Bakhtin (1981, 293) argued, ‘the word in language is half someone else’s,’ indicating dialogue and multivocality, i.e. words carry multiple mean-ings, interpretations, and they themselves are contested terrains. As such, subordinate groups appropriate dominant discourses expropriating and forcing them ‘to submit’ their own intentions and accents to construct collective claims and identity.

Regardless of the nature of the claims articulated, collective actions have constitutive impacts in modern democracies; they not only reveal the political agency of the individuals and groups, but also create a relational and contingent space of negotiations between the power-holders and the protesters. Through articulation of claims during demonstrations diverse individual self-understandings emerge and merge as public pro-nouncements, which are communicated both among the participants and with the power-holders. In that sense, both the 2007 and 2013 anti-AKP demonstrations, along with the AKP officials, were engaged in a dialogical struggle to redefine the collectivities of nationhood and citizenship in Turkey.

Inspired by Brubaker’s suggestion that it is the political actors, policy-makers and the challengers that invoke or evoke nation as a putative entity

in order to justify the claims of the collectivity in action,5 I argue that the participants of the two episodes of protests, by describing and designating their sense of membership in a political community, are actually in the process of the reproduction of Turkish polity and nationhood. Both the 2007 demonstrations and the Gezi protests were moments of negotiation of nationhood with crowds that gathered in public spaces who were expe-riencing and contesting diverse meanings of national unity (i.e. what are the goals, ideals, aspirations of this collectivity), nationhood (i.e. a sense of belonging to a cultural and political community) and citizenship (i.e. culturally understood, legally acquired membership).

I argue that with the Gezi protests, a new, anti-authoritarian sense of nationhood was invoked, in contrast to the 2007 mobilisation, where prevailing ideas and policies of Turkishness with a state-imposed unity and uniformity were evoked. In 2007, the demonstrators were bringing and calling memories, images and sentiments from the past, whereas during the Gezi protests, there were earnest requests for a new collectivity, calling forth and putting into effect a new sense of community. This shift from evoking nationhood, i.e. a retrospective homogeneity and a nationalism of yesteryear, to invoking nationhood, which aims to create a new and diverse collectivity, is a product of unprecedented expansion and broadening of democratic participation in Turkey that has been taking place under the AKP, a party which was later deemed by some to have become corrupt and slipping into authoritarianism, despite immense support from almost half of the Turkish voters.6

2007 – Nation-Evoking Demonstrations

The 2007 Flag demonstrations were organised by two staunchly nationalist organisations: the Association for Ataturkist Thought (Atatürkçü Düşünce Derneği, ADD) and the Association for the Support of Contemporary Living (Çağdaş Yaşamı Destekleme Derneği). The former identifies itself as a laicist

5 Here, Brubaker follows Pierre Bourdieu’s conceptualisation of the ‘performative character’ of participants’ reification of their group, i.e. they ‘contribute to producing what they apparently describe or designate’ (Bourdieu 1991, 220). Brubaker (2004, 69) characterises this group-making practice as ‘generic to political mobilisations and representation’ and summarises this process as follows: ‘by invoking groups, they seek to evoke them, summon them, call them into being […] to stir, summon, justify, mobilize, kindle and energize’ (Ibid., 53).

6 http://www.opendemocracy.net/kumru-Toktamış-emrah-celik/exploring-erdo%C4%9Fan %E2%80%99s-unwavering-support-in-turkey.

(state-secularist)7 organisation that promotes the ideas of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey, and aims to defend his reforms against the imminent threats of Sharia and separatism.8 The latter was created by a group of female academics who subscribe to a statist feminism, highlighting the Republican principle that incorporated and institutional-ized putative political and social rights for women in Turkey.9 As staunch adherents of state-secularism and supporters of the military’s role as the guardian of the Republican principles, in the spring of 2007 these two urban elite organisations called for a series of protest demonstrations throughout the main urban centres with the active support and participation of a dozen other nationalist and state secularist associations – all of which were later active at Gezi – such as the DİSK, Istanbul Bar Association, Youth Union of Turkey (Türkiye Gençlik Birliği, TGB), Confederation of Public Workers’ Union (Kamu Emekçileri Sendikaları Konfederasyonu, KESK), Union of Patriotic Forces (Vatansever Kuvvetler Güç Birliği Hareketi), Association of Women of the Republic and left and centre-left parties.

The call was actively supported by the Turkish Armed Forces when the military made its support clear by publicly echoing the concerns of the organisers regarding the possible election of one of the founders of AKP, Abdullah Gül, whose wife publicly dons the Islamic headscarf. The then chief of staff, General Yaşar Büyükanıt, stated that the election of the new head of state ought to conform to ‘the foundational values of the Republic, the unitarian nature of the state and sincerely following the laicist democratic state.’10 Freedom of press was heavy-handedly undermined even when journalists from mainstream media questioned the civilian quality of the planned demonstrations and expressed discomfort about the interventionist traditions of the military.11

In 2007, there were a total of ten well-organised, heavily attended and orderly ‘Republic’ demonstrations in nine Turkish cities and one German city. In Ankara, 500,000 participants marched to Anıtkabir, the memorial of the Founder of the Turkish Republic, in the aftermath of the actual dem-onstration with no intervention from the security forces. The most popu-lated demonstration took place in Izmir with over a million participants.12

7 For distinctions between Turkish laicism and secularism, see Houston 2013. 8 http://add.org.tr/?page_id=2280. Accessed 1 June 2014.

9 http://www.cydd.org.tr/sayfa.asp?id=22. Accessed 1 June 2014. 10 http://arsiv.ntvmsnbc.com/news/405388.asp.

11 Weekly NOKTA’s headquarters were raided, computer hard-drives were seized and the

publication of future issues was effectively ended. 12 http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6604643.stm.

Donning and displaying the Turkish flag, participants’ slogans expressed three sets of concerns:

a) the threat of an Islamist takeover, evoking the Republican principle of state-secularism: ‘Claim your Republic’; ‘Turkey is Laicist, will Remain Laicist’; ‘neither Sharia, nor a coup, but a totally independent Turkey’; ‘The roads to Çankaya [Presidential Palace] are closed to Sharia’; ‘We don’t want an imam in Çankaya’; ‘Turkey sobered up and the imam passed out!’; ‘Forefather, rest in peace, we are here.’

b) protesting foreign support, evoking anti-imperialism: ‘We want no ABD-ullah as president!’ [ABD is the Turkish acronym for US]; ‘Neither EU, nor US. Totally independent Turkey!’; and again ‘neither Sharia, nor a coup, but a totally independent Turkey’ [‘totally independent’ alluding to the anti-imperialist Marxist-Leninist left of the 1960s and 1970s]. c) indicating the backward, primitive, religious qualities of the AKP

in direct confrontation with the prime minister and demanding his resignation: ‘Cabinet, resign!’; ‘Tayyip take a look at us, count how many of us there are!’ [a direct reference to the prime minister’s former remark about the numbers of the protesters]; ‘Turkey sobered up and the imam passed out!’ [pun]; ‘Even Edison regrets it!’ referring to AKP’s emblem, the light bulb; ‘As the sun rises, light bulbs dim;’ ‘We came with our mother, where are you?’ [on mother’s day, as direct confrontation with one of the former remarks of the prime minister]; ‘The Islamic call to prayer, the peal of church bells, and the ceremony of the synagogue are all listened to with respect in this city’ [confronting the prime minister’s remark that Izmir was an infidel city]; ‘Buy Tayyip, get Aydın Doğan for free!’ [Doğan is the media mogul whose media outlets gave little coverage to the demonstrations].13

With these slogans and several public speeches, the protesters identified their goal of a republican Turkey as an ‘enlightened nation-state with integrity and honour, and guided by [principles of] science’ as opposed to ‘reactionaries’ (a euphemism about Islamism), separatists (a euphemism about Kurdish nationalism), collaborators of global exploitation (alluding to the anti-imperialist foundational myths of the post-World War One era), and conspiracies that aim to establish an anti-laicist education system.14

They were responding to Prime Minister Erdoğan whose populist re-marks were undermining the laicist claims as elitist, by identifying him as

13 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Republic_Protests#Slogans_from_the_rallies.

an ignorant religious reactionary who lacked the modern statesmanship as envisioned by the founders of the Republic. A nineteenth-century modernist discourse was apparent during the demonstrations as the participants expressed their fear of what they perceived as ‘religious reactionary’ politics, and arguing that religious social representation was not supposed to be an integral part of Turkish politics even if represented by democratically elected leaders and supported by large portions of society. The irony was that the protestors identified the ‘backward, reactionary’ AKP as the ally of the enlightened yet ‘imperialist’ Europe.

The 2007 protests were well organised, strategic mobilisations of a para-doxical elite mob-spirit that seemed to be fearful of losing its monopoly of the public discourse on nationhood and citizenship. Their understanding of Turkishness and Turkish nationhood was one of following the top-down ideals of a modernizing state, depicting the population and its ideals as designed and designated by the republican principles of cultural uniformity and anti-religious exclusiveness, guarded by the military establishment.

Gezi – Summer 2013

Contrary to the ex-nihilo explanations regarding the origins of the Gezi mobilisation, there were almost two years’ worth of long strategic organis-ing, involving professional, neighbourhood and community organisations. The rapid escalation of protests throughout the country in the month of June is often described as a massive, spontaneous and unorganised response to indiscriminate police brutality against peaceful protestors. In fact, the original protest was a well-organised strategic action coordinated by lo-cal residents of Taksim and the TMMOB (the leading groups and active participants of the Taksim Solidarity, which would later incorporate more than 100 professional and civic organisations) against the redevelopment plans of the government and the Mayor, initiated in 2009. Since its inception, Taksim Solidarity was staunchly critical of the AKP regime, not only in terms of its economic programme, but also its social and cultural policies and its constituents’ cultural visibility.15

As the protests expanded in scope and number, the original instiga-tor, Taksim Solidarity, emerged as the umbrella organisation of çapulcus and çapulling, fully re-appropriating a formerly pejorative term that was originally used by the prime minister to discredit the demonstrators. This