CONTINUITY AND CHANGE: AN ANNALES APPROACH TO THE LATE CHALCOLITHIC PERIOD IN NORTH MESOPOTAMIA

A Master’s Thesis

by ŞAKİR CAN

Department of Archaeology İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University

Ankara May 2018

CONTINUITY AND CHANGE: AN ANNALES APPROACH TO THE

LATE CHALCOLITHIC PERIOD IN NORTH MESOPOTAMIA

The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of

İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University

by

Şakir Can

In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS

THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY

İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA

vi ABSTRACT

CONTINUITY AND CHANGE: AN ANNALES APPROACH TO THE LATE CHALCOLITHIC PERIOD IN NORTH MESOPOTAMIA

Can, Şakir

M.A., Department of Archaeology

Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Marie-Henriette Gates May 2018

The semantic context of the cultural patterns of the past is beyond our perception. This fact, regardless of time and space, thus, makes any type of social organizations that existed in the past complex and transitive. Bearing in mind this fact, this study aimed to analyze the Late Chalcolithic period (ca. 4500-3000 BC) in an extensive area of north Mesopotamia with archaeological traces of an increasing socio-cultural, socio-economic, and socio-political complexity through the Annales School of

History paradigm, which divides time into geographical time, social time, and individual time. Within this division, geographical time (longue durée) refers to the role of environment and geography on the nature and development of the northern communities at the regional level. Social time (conjoncture) provides a perceptible rhythm of indigenous cultural phenomena in north Mesopotamia (ca. 4500-3700 BC) prior to the Uruk culture of southern Mesopotamian origin, and a certain degree of social mobility, history of communities and their ideologies (mentalité) after the Uruk expansion (ca 3700-3000 BC). The Uruk phenomenon in north Mesopotamia can be perceived in social time. At another level, individual time (évènement), which takes historical events as the reference, coincides with the establishment of the Uruk colonies at Tell Sheikh Hassan, Habuba Kabira Süd, and Jebel Aruda in the Middle Euphrates Basin. In comparison with the earlier assessments, this analysis shows that an interpretation of continuity and change in total history (histoire totale) of the Late Chalcolithic period of north Mesopotamia is possible with the Annales paradigm. It

vii

also shows that north Mesopotamia, in the long term, hosted a number of cultural patterns; thus, provides culturally accumulated continuity, while different cultural influences and interactions, in several cases, played a key role in cultural changes. The interpretation of this thesis based on archaeological excavations, surveys carried out in north Mesopotamia, as well as previous views on the Late Chalcolithic period.

viii ÖZET

DEVAMLILIK VE DEĞİŞİM: KUZEY MEZOPOTAMYA GEÇ KALKOLİTİK DÖNEMİNE BİR ANNALES YAKLAŞIMI

Can, Şakir

Yüksek Lisans, Arkeoloji Bölümü

Tez Danışmanı: Doç. Dr. Marie-Henriette Gates Mayıs 2018

Geçmişin kültürel örüntülerinin anlamsal bağlamı algılarımızın ötesinde olması, bu geçmişin içinde zamandan ve mekândan bağımsız olarak varlık gösteren herhangi bir sosyal organizasyon biçimini karmaşık ve geçişken yapmaktadır. Bu gerçekten hareketle, bu tez çalışmasında kuzey Mezopotamya coğrafyasının Geç Kalkolitik sürecinde (M.Ö. 4500-3000) artan sosyo-kültürel, sosyo-ekonomik ve sosyo-politik karmaşıklığın arkeolojik izlerinin bir bütün tarihsel okuması için zamanı coğrafik, sosyal ve bireysel olarak bölümleyen Annales yaklaşımı esas alınmıştır. Coğrafik zaman (longue durée), kuzey Mezopotamya toplumlarının doğasında ve gelişiminde çevre ve coğrafyanın oynadığı rolün bölgesel düzlemde izlenmesine olanak tanır. Sosyal zaman (conjoncture), kuzey Mezopotamya’da güney Mezopotamya kökenli Uruk kültürünün öncesinde yerel kültürel olguları (M.Ö. 4500-3700) ve sonrasında belli ölçülerde var olan sosyal hareketliliği, toplumların tarihi ve ideolojilerini (mentalité) anlamamızı sağlamaktadır. Sosyal zamanda algılanabilen kuzey

Mezopotamya’daki Uruk olgusu ise, tarihsel olaylar referans alan bireysel zamanda (évènement) Orta Fırat Havzası’nda Tell Sheikh Hassan, Habuba Kabira ve Jebel Aruda’daki Uruk kolonilerinin kurulmasıyla örtüşmektedir. Böylelikle, kuzey Mezopotamya’nın Geç Kalkolitik döneminin tüm tarihinde algılanabilen devamlılık ve değişimler Annales paradigmasıyla açıklanmıştır. Ayrıca, uzun vadede birçok yerel kültürel örüntüye ev sahipliği yapan kuzey Mezopotamya’daki kültürel birikim kültürel devamlılığı sağladığı, farklı kültürel etki ve etkileşimlerin belli bölgelerde

ix

kültürel değişimlerde de rol oynadığı sonucuna ulaşılmıştır. Bu değerlendirme, kuzey Mezopotamya’da yapılan arkeolojik kazılar, yüzey araştırmalar ile Geç Kalkolitik dönem için yapılan yorumlamalara dayandırılmaktadır.

x

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This M.A. thesis would not have been possible without the support and guidance of several important people in my life. First of all, I would like to express my profound gratitude to my advisor Assoc. Prof. Dr. Marie-Henriette Gates for her patience, motivation, immense knowledge, and supportive guidance during the course of this study. Besides my advisor, I would like to gratefully thank my thesis commitee: Dr. Charles Warner Gates for guiding me through the methodological and technical issues, and Assoc. Prof. Dr. Rana Özbal, for her insightful and encouraging comments.

My deep gratitude also goes to Prof. Dr. Ayşe Tuba Ökse. I will always be proud to have been her student. She has motivated, guided and supported me throughout my educational life. I would like to express my sincere thanks to Özlem Ekinbaş, an admirer of Fernand Braudel, for her profound knowledge and for always keeping me on the straight and narrow during the course of my work. I also owe thanks to Aydoğan Bozkurt, who is like my elder brother, always giving me his spiritual support. My sincere thanks also go to Assoc. Prof. Dr. Çiğdem Atakuman for her wise counsel in my academic and personal life. I sincerely thank Asst. Prof. Dr. Haluk Sağlamtimur and Dr. Tatsundo Koizumi for sharing their unpublished works and valuable ideas with me. I would like also to thank Martina Massimino and Rachel Starry for giving me the opportunity to use the libraries of the University of Durham and Bryn Mawr College.

Perhaps no words can express my heartfelt gratitude to my family who deserve my deepest gratitude: especially my Mum and Dad, who have always stood by me throughout my life; my brothers, sisters and brother-in-law for their unflagging love and support no matter what the issue. With thanks to them, I am who I am. I could not have done this thesis without them. I cannot forget thanking my dearest friends who are like my family: İlhan Yaşar Danış, Cevat Sevinç, Bekir Dabakoğlu and Mehmet Bulut for their positiveness and unflagging encouragement throughout my entire life, as well as my cousin Nizameddin Dildirim for being part of my family.

xi

Last but not least, I would like to express my special thanks to my former dorm manager Nimet Kaya, who passed away last summer, and Nermin Karahan for their help at all times. I owe my sincere gratitude to the rest of the faculty members of Bilkent Archaeology Department for their academic and personal support and for providing a stimulating intellectual environment. I am especially deeply indebted to my dear friends Çağdaş Özdoğan, Emre Dalkılıç, Zeynep Akkuzu, and Rida Arif for sharing a close and enduring friendship. I will always be grateful for their support and guidance in my life. I am especially grateful to Roslyn Sorensen and Zeynep Olgun for correcting my English grammar mistakes and for providing useful insights about my thesis. Finally, I would like to thank my friends Emrah Dinç, Umut Dulun, Onur Hasan Kırman, Onur Torun, Çağkan Tunç Mısır, Umer Hussain, Abdullah Waseem for their companionship. And thank you very much Tuğçe Köseoğlu for teaching me the GIS program that made the creation of those thesis maps easier.

xii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... vi

ÖZET... viii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... x

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... xii

LIST OF TABLES ... xiv

LIST OF FIGURES ... xv

CHAPTER 1 ... 1

INTRODUCTION ... 1

CHAPTER 2 ... 5

DIFFERENT “WAVES OF TIME”: THE ANNALES SCHOOL OF HISTORY ... 5

2.1. Annales School of History ... 5

2.2. Discussion ... 11

CHAPTER 3 ... 12

THE LC 1 AND 2 PERIODS IN NORTHEAST MESOPOTAMIA ... 12

3.1. The Ubaid Phenomenon ... 12

3.2. Transition from Late Ubaid to the Late Chalcolithic Period ... 13

3.3. LC 1-2 periods in northeast Mesopotamia ... 15

3.3.1. Iraqi Jazeera ... 15

3.3.2. The upper Tigris Basin ... 20

3.4. Discussion ... 25

CHAPTER 4 ... 26

THE LC 1 AND 2 PERIODS IN NORTHWEST MESOPOTAMIA ... 26

4.1. LC 1 and 2 Periods in Northwest Mesopotamia ... 26

4.1.1. The Khabur Basin ... 26

4.1.2. The Balikh Basin ... 33

4.1.3. The Middle Euphrates Valley ... 37

xiii

4.1.5. The Altınova Plain ... 48

CHAPTER 5 ... 54

CULTURAL LANDSCAPE IN NORTH MESOPOTAMIA DURING THE LC 3-LC 5 PERIODS ... 54

5.1. The Uruk Phenomenon in the Homeland ... 54

5.1.1. Mysterious bowls: Beveled Rim Bowls ... 58

5.1.2. The Uruk Expansion as a “Corollary” ... 59

5.2. Local and Interregional Complexity of North Mesopotamia during the LC 3-5 Periods ... 60

5.2.1. Northeast Mesopotamia during the LC 3-5 Periods ... 61

5.2.2. Northwest Mesopotamia during the LC 3-5 Periods ... 67

5.3. Discussion ... 77 CHAPTER 6 ... 78 CONCLUSION ... 78 REFERENCES ... 89 TABLES ... 110 FIGURES ... 112

xiv

LIST OF TABLES

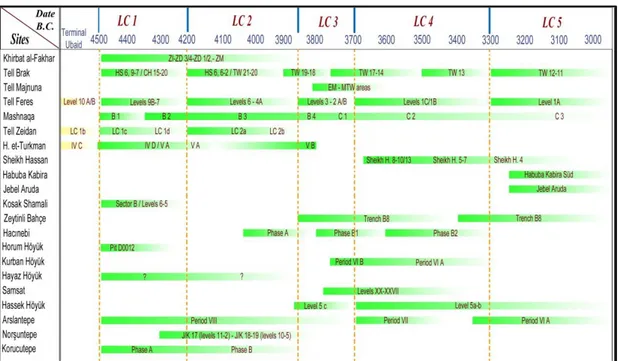

Table 1. Chronological framework of the Late Chalcolithic period and related levels of excavated sites in northeast Mesopotamia (after Rothman, 2001a: 7, Table 1.1). ... 110 Table 2. Chronological framework of the Late Chalcolithic period and related levels

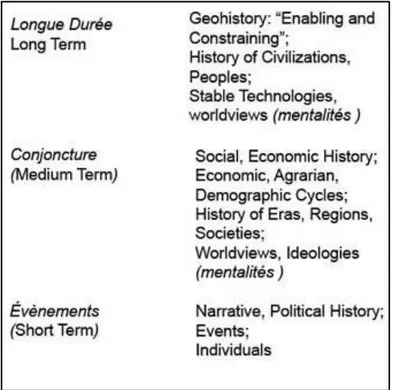

of excavated sites in northwest Mesopotamia (after Rothman, 2001a: 7, Table 1.1). ... 110 Table 3. Braudel’s time division of histoire totale (after Bintliff, 2010: 119, fig.1). ... 111 Table 4. Annales paradigm and pervious approaches on the LC period of north

xv

LIST OF FIGURES

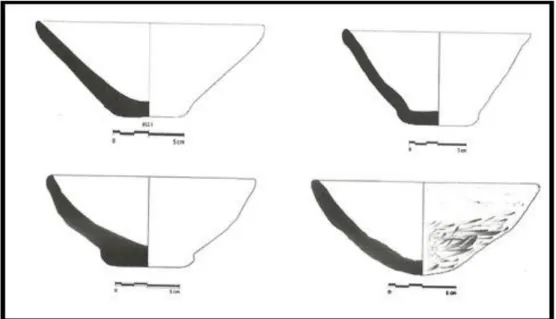

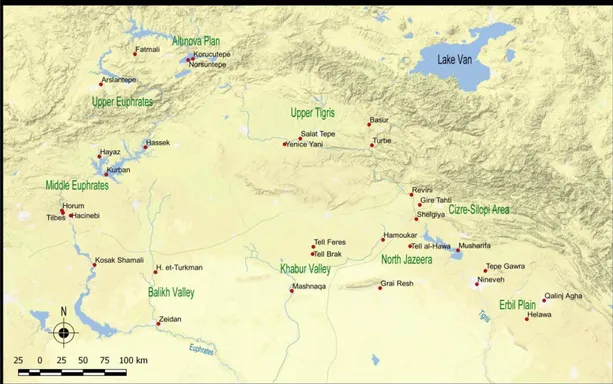

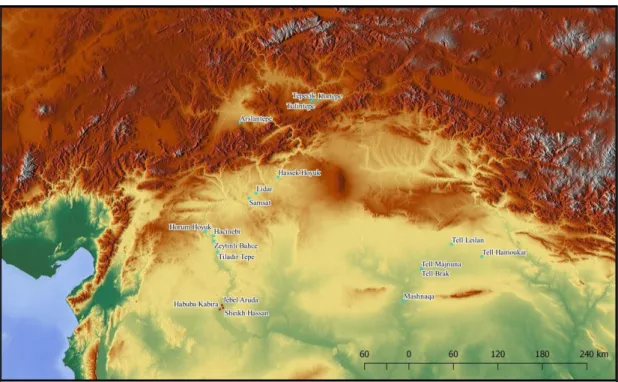

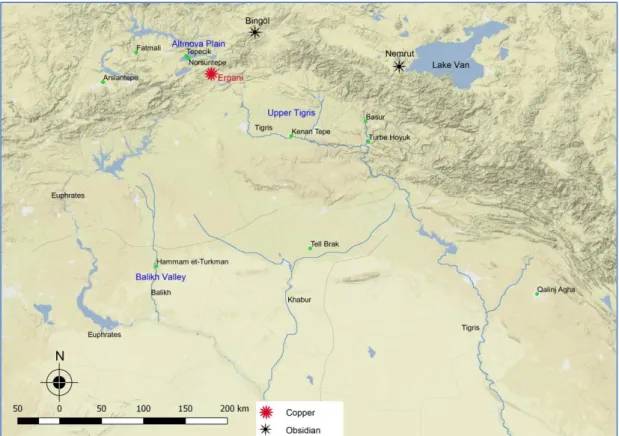

Figure 1. Map showing the main area of study and the main Late Chalcolithic sites in north Mesopotamia (adapted from QGIS). ... 112 Figure 2. Regional diversities of Coba bowls with four main types (Baldi, 2012a:

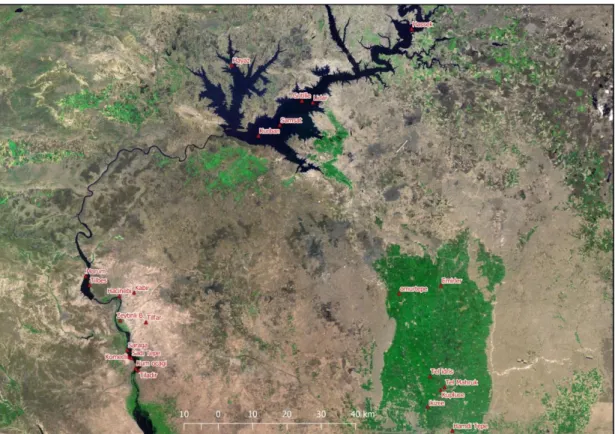

414-415, figs.2-3). ... 112 Figure 3. Map showing the main LC 1-2 sites in north Mesopotamia (adapted from

QGIS). ... 113

Figure 4. Beveled Rim Bowls from excavated and surveyed sites (map adapted from QGIS: picture; Cluzan, 1993: 87, fig. 84b: drawing; Pearce, 2000: 136, fig. 12). ... 113

Figure 5. Map showing sites with LC 3-5 archaeological contents in northeast

Mesopotamia (adapted from QGIS). ... 114

Figure 6. Map showing sites with LC 3-5 archaeological contents in northwest

Mesopotamia (adapted from QGIS). ... 114

Figure 7. (a) Architectural plan of the Feasting Hall (Oates et al. 2007: 595: fig. 11); (b) the depiction showing tasselled pots with carrying devices and the

depiction of (lion?) as an early Anzu-Bird (Oates & Oates, 1997: 294: fig. 14); (c) Numerical tablets from Tell Brak (Jasim & Oates, 1986: Fig. 2a).. 115 Figure 8. Map showing main sites located in the Middle Euphrates Basin and the

Harran Plain (adapted from QGIS). ... 115 Figure 9. The reinterpretation of LC 3 pottery (a) in the LC 5 period at Zeytinli

Bahçe (b) (Frangipane, 2010: 200-201, figs. 5 and 6). ... 116

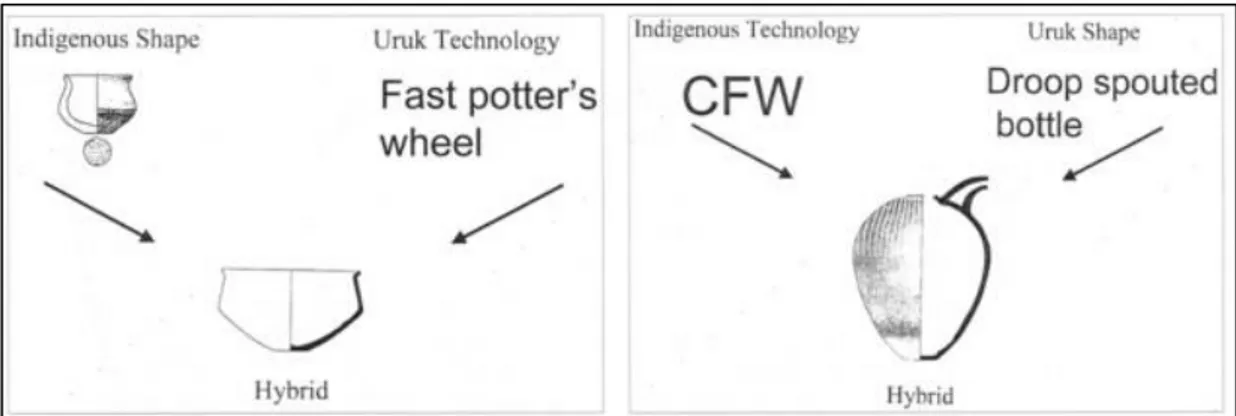

Figure 10. Local and Uruk style Hybridized pottery assemblage of Hassek Höyük (Helwing, 1999: 96, figs. 4a-4b). ... 116

xvi

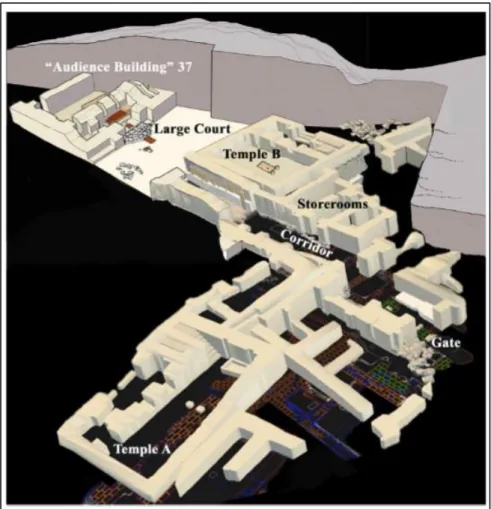

Figure 11. Reconstruction of Arslantepe period VI A “palatial period” (Frangipane, 2017a: 37, fig. 13). ... 117

Figure 12. (1) Arslantepe period VI A wall painting in the audience building; (2) Uruk type seal from Arslantepe; (3) Uruk seal from Warka (Tırpan, 2013: 478-479, figs. 20-5 and 20-6) ... 117 Figure 13. Arslantepe period VI A Temple B and interior architectural elements

(Tırpan, 2013: 476, fig. 20-3). ... 118

Figure 14. Map showing the location of main highland resources and sites discussed in chapter 6 (adapted from QGIS). ... 118 Figure 15. The close proximity of the LC period sites near rivers in north

Mesopotamia (adapted from QGIS). ... 119 Figure 16. (a) Architectural plan of White Temple at Uruk (Roaf, 1995: 430, fig. 7);

(b) Stratum 7 building in Level VB at Hammam et-Turkman (Lupton, 1996: 29, fig. 2.13). ... 119

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Space and environment, in which all types of social structure exist, make social groups a part of a continuous cultural pattern in the context of relationships they have established with each other and with others. The resulting picture can be that

geography and environment provoke both inherent losses and gains in any society in a specified region. Thus, these cultural patterns may reveal changes created by cross-cultural intersections arising from the interaction among transhumant groups and sedentary groups or the like. It is in this regard that the Late Chalcolithic period (LC hereafter) (ca. 4500-3000 BC) in Mesopotamia is an era during which we may attempt to find the relationship that individual and society have developed with urbanization, city, and state (Algaze et al. 1989; Algaze, 1993; Oates et al. 2007; McMahon et al. 2007).

As Braudel (2016: 218) suggests, each society or social group joins in a series of civilizations that have ties, while at the same time they can be very different from each other. Starting from this point of view, in this thesis, cultures, cultural changes and associated transformations, and the changes created by cross-cultural

intersections among these cultures will be investigated through the time division of Fernand Braudel1 in a huge geographical area of northern Mesopotamia during the

LC period, fixed between ca. 4500-3000 BC in time and space (Figure 1). This study aims to explain social, economic, and political continuity and change in north

Mesopotamia during the LC period through an Annales approach. It should, however, be kept in mind that societies and their material cultures or symbolic

2

worlds cannot be squeezed between fixed times. Nor can they be generalized in a specified region.

Taking into consideration the above lines, we cannot reduce the economic, political, and social landscapes of LC Mesopotamia by a series of evocative univocal words such as homogenous, equal, monotype, standardized, and uniform. In fact, societies, like civilizations, have a dynamic space equipped with geographical advantages and constraints. This dynamism in space contains the traces of constant and cumulative exertion that is being shaped by humanity and takes centuries and even millennia. That is to say, humanity is the key agency of reflective construction by the self (Braudel, 1995: 9). It recalls then what Fernand Braudel emphasizes for the long-term (longue durée) as the role of environment and its impact on a given society or the relationship between the individual who is a member of social group and the “inanimate” (Braudel, 1972: 20). Therefore, in the Mesopotamian case as well, we should bear in mind that all kinds of socio-political developments and economic trends cannot be materialized in all the sub-regions equally, simultaneously and similarly during the LC period.

On closer examination, the two spheres of Mesopotamia (north and south) underwent far-reaching socio-political developments. While the alluvial plains of south

Mesopotamia witnessed the emergence of urbanized state societies during the 4th millennium (ca. 3800-3100 BC), known as the Uruk period (Adams, 1981; Wright and Johnson, 1975; Nissen, 1988; Pollock, 1992; 2001), the nearly contemporary period in north Mesopotamia had an almost completely different socio-political horizon. For instance, there was neither state formation process nor large-scale urbanization process like in south Mesopotamia, except for few sites such as Tell Brak and Hamoukar, until the mid-third millennium BC (Wattenmaker, 2009: 107; Çevik, 2007: 132). Nonetheless, it is suggested that urbanization began to appear in north Mesopotamia at Tell Brak as early as the late 5th millennium BC (Oates et al. 2007; McMahon et al. 2007). Similarly, recent excavations conducted at Arslantepe demonstrated that a very complex socio-economic system developed in Greater Mesopotamia before the Uruk Expansion (Frangipane, 2001a).

3

At this juncture it is important to explain what the Uruk expansion is. In the 4th millennium BC, the southern part of Mesopotamia was apparently suffering from a lack of natural and mineral resources (Algaze, 1989; 1993; 2001a) and agriculture, the basic subsistence strategy in the alluvial plains, was only available through irrigation (Tamburrino, 2010: 29). These conditions together with increasing interest for raw materials, such as metal ores, timber, and semi-precious stones resulted in a colonializing activity, from the Uruk-centric viewpoint, far from their homeland in what may be called its periphery. Colonies were founded at sites like Tell Sheikh Hassan, Habuba Kabira Süd, and Jebel Aruda in the Middle Euphrates basin (Figure 1) during the mid-4th millennium BC (LC 4) and lasted for a few centuries until they were abandoned during the final stages of the LC 5 (Algaze et al. 1989; Algaze, 1993). So then why did these colonies come from South to the North and subsequently abandon their settlement?

This expansion brought about a widespread distribution of material culture of southern origin, such as pottery, architecture, glyptic, and ideology (mentalité) in north Mesopotamia, which is why the Uruk ‘corollary’ has been called the “Uruk World System” (Algaze, 1993). Based upon the “core-periphery” dynamics,

Algaze’s Uruk World System has been challenged by Stein, who put two alternative explanations forward (“distance-parity” and “trade diaspora”) to understand the nature of relationship between north-south Mesopotamia (Stein, 1999a; 1999b) and by Helwing (1999) who put emphasis on a hybridization process as a result of cross-cultural interaction.

If we now return to the starting point, nothing is coincidence. That is to say, the fascination with the Uruk phenomenon in archaeological research attracted many archaeologists. Did this world of events, actions, developments, and interactions occur at any site suddenly? Certainly not. Since Late Chalcolithic extends over five periods (LC 1-5) (Table 1 and 2), it seems that we have at a minimum 700 years of north Mesopotamian cultures, which, nonetheless, remained like a ‘dark age’. Most research has focused instead on the Uruk phase in the region (Carter & Philip, 2010; Marro, 2012b) in addition to old studies. This period of the LC era is called the Post-Ubaid (Marro, 2012a), LC 1-2 periods, Terminal Post-Ubaid, or Local LC (Rothman, 2001a: 5-9). It must be emphasized that 700 years of the LC period, primarily LC

1-4

2, were already carrying some elements of the previous so-called Ubaid period, another southern cultural movement, though not equally at all sites.

In comparison to the alluvial plains of south Mesopotamia, north Mesopotamia’s more varied environment, with more rugged terrains and suitable lands, and desirable resources, depended on rain-fed agriculture (Tamburrino, 2010: 29). The area of study that constitutes the main theme of this thesis is north Mesopotamia. In this study, this term will refer to the Erbil Plain, north-east Jazeera, the Khabur and Balikh basins, the Middle and Upper Euphrates basins, the Altınova plain, and the Upper Tigris basin (Figure 1).

In order to place all the cultural phenomena of the LC period in north Mesopotamia into the Annales paradigm, it is necessary to review what Braudel means by his philosophy of history based on the division of three temporal scales. Therefore, this thesis’s chapter 2 will focus on Braudel’s time division, whose suitability to

archaeological interpretation will be illustrated by two cases studies in two discrete areas and eras.

Drawing specifically upon a variety of the excavated sites and surveyed regions of north Mesopotamia together with archaeological interpretations, chapters 3 and 4 will explain the degree to which continuity and change took place in north Mesopotamia between ca. 4500-3800 BC. It should be noted that this large geographical area is intentionally divided here into two zones: northeast and

northwest Mesopotamia. This division aims to make their differences clearer for the reader. The documented data of the LC 1, 2, and early 3 periods in northeast

Mesopotamia will be presented in chapter 3 by following the Tigris River and its tributaries, while the same periods in northwest Mesopotamia will be discussed in chapter 4 by following the Khabur, Balikh, and Euphrates rivers.

Chapter 5 will analyze the LC 3, 4 and 5 periods throughout north Mesopotamia by looking at both the indigenous and Uruk archaeological materials. Chapter 6 will conclude general assessments of regional continuity and change, followed by an evaluation of north Mesopotamia based on the Annales approach.

5

CHAPTER 2

DIFFERENT “WAVES OF TIME”: THE ANNALES SCHOOL OF

HISTORY

2.1. Annales School of History

The Annales School of History was founded by a group of history scholars during the 1920s under the leadership of Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre (Huppert, 1982: 510). For a better understanding of its usefulness for archaeological analysis, a set of conspicuous archaeological case studies that have been inspired by Annales will be discussed. It should be noted that the main movements of the Annales separate into four different generations2, each of which tended to open up growing perceptions of time and space in history. This study will mostly draw upon the second generation of the Annales, which is attributed to Fernand Braudel, as it is the one most relevant to the subject matter of this thesis. Though the first generation is not directly related to the subject of thesis, it is necessary to briefly describe previous approaches to understand Braudel’s philosophy of history, since he was influenced by his predecessors and took one further step to resolve the study of “time” in history.

The initial attempts of these scholars towards a fresh insight into history were presented by their journal, “Annales d’histoire economique et sociale”, founded in 1929, and which eventually gave its name to their approach to history (Huppert, 1982: 510; Knapp, 1992a: 4). In due course, many scholars of the Annales took the advantage of a number of disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, economics, and geography and contributed to different and new approaches to perceiving history (Bintliff, 1991: 5; Knapp, 1992a: 4; Sayegh & Altice, 2014: 33).

2 For further detail about four generations of the Annales School of History see Knapp, 1992b;

6

Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre, as the first generation of the Annales, paid more attention to the concept of materialist history and tried to understand culture through society and through economy (Wallerstein, 1982; 110-111; Bintliff, 1991: 5; Knapp, 1992a: 5; McGlade, 1999: 146; Sayegh & Altice, 2014: 33). The initial studies, which drew mainly upon sociology, began to examine the structure of society and changes in society over time, rather than the narrative of events and individuals (Wallerstein, 1982: 110-111; Bintliff, 1991: 5; Knapp, 1992a: 5; McGlade, 1999: 146). In doing so, making a “total history” based on social, functional and structural approaches was superior to focusing on the foreground of historical events

(McGlade, 1999: 146; Sayegh & Altice, 2014: 33).

Unlike his predecessors’ understanding of sociological history, Fernand Braudel, a student of Lucien Febvre, was more interested in geology and geography in order to establish the “total history” (histoire totale) (Braudel, 1972: 23). In his eminent work The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, Braudel segmented three temporal levels of the historical process: environment and geographical structures (longue durée); socio-economic sequence, demographic cycles, history of eras and regions (conjoncture); and narrative, socio-political events, individuals (l’ histoire évènementielle) (Table 3) (Braudel, 1972: 20-21). He also argued that history is a sequence of processes that take place at different

wavelengths of time and levels (Braudel, 1972). One should, however, bear in mind that this does not mean that there are certain rules and trends in each time that make precise distinctions from one level to another. As he well presented in his own thesis (The Mediterranean) the separation of various planes of history is essential to make and describe a history: in other words, to divide historical time into geographical time (longue durée), social time (conjoncture), and individual time (l’histoire évènementielle). The result aims “…to divide man into a multitude of selves…” (Braudel, 1972: 21; 1980; 25-52). This consequently meant that social time should be evaluated in a multidimension scale (Knapp, 1992a: 6).

One of the most important contributions of Braudel is the long-term phase (longue durée), which is mostly based on the relation of the human to the environment, in which there is a slow progression of changes, permanent recurrence and cycles (Braudel, 1972: 20). As the changes cannot be perceived in the historical events,

7

Braudel interprets them as the dynamics of the long-term (longue durée) (Braudel, 1972: 20). These dynamics can be preponderant and slow changes in technologies and lasting cultural characteristics such as ideologies or worldviews (Bintliff, 1991: 7). In terms of temporality, while long-term may cover centuries-long background, it is mostly concerned with “biological, environmental, and social interrelationships”, what may be named “human ecology” today (Knapp, 1992a: 6).

In Braudel’s structural history, longue durée provides a useful insight into better understanding historical developments together with their causes and dynamics in a specified region. To do this, it is also crucial to recognize the historical developments in both temporal and geographical scale, the developments of both the center and periphery, the changes over time, and the factors that influence the development of a particular region (Ames, 1991: 935). According to Braudel, we can perceive and recognize “macrophenomena”, which are long-term, but “microphenomena”, which are at the scale of events, can hardly be perceived as indefinite. Therefore, events occurring in the course of history can only be meaningful when they are scrutinized within a broader conjuncture (Knapp, 1992a: 6).

Although Braudel underlies the necessity of geography for a longer-term history, it may be misleading if one relates his concern to the simple description of physical environment. Rather, in Braudel’s schema, the ecological determinism in conjunction with the long-term concept creates a balance between the momentary event and the constant process in a unitary socio-historical basis (Knapp, 1992a: 6). Therefore, he places the social phenomena into their physical setting, which moves at a much slower rate (Hodder, 1987: 3, see also Braudel, 1972, Chapter 1: 25-101).

Unlike those traditional books in which the introduction of geographical history is limited to geographical features such as mineral resources, flora and fauna diversities that are listed and not mentioned again, Braudel emphasizes that a history of

“timeless past” or of human interaction with the “inanimate” should not be neglected (Braudel, 1972: 20). As such history is “timeless”, long-term “structures” for Braudel are first concerned with duration and then with their impacts on human action

8

his understanding of “macrohistory” are the physical and material factors (“inanimate”) that take place in a long period of time (Knapp, 1992a: 6).

Fernand Braudel in his work on the Mediterranean especially underlines the role of environment and geography in illuminating the dark side of Mediterranean history. In other words, a certain array of factors related to geography must be brought together to shed light on Mediterranean history, including landscapes, images as well as the human impact and even the relevant data from other periods before and after. By doing so, all the cohesive data of time and space offer us an opportunity to comprehend history in a slow motion where permanent values can be perceived (Braudel, 1972: 23). Consequently, geography remains a dynamic process that makes us able to see the historical realities in the long-term in a very wide perspective, as Braudel emphasizes the continuity of geography that “… is no longer an end in itself but a means to an end.” (Braudel, 1972: 23).

At another temporal level, conjoncture is related to the social history, history of groups and groupings with “slow but perceptible rhythms” (Braudel, 1972: 20). Medium-term (moyenne durée) events concerning the shaping of human life have several generations or centuries of background (Braudel, 1980: 27; Bintliff, 1991: 7; 2004; 176). Braudel distinguishes two distinct levels of conjoncture: intermediate level conjunctures deal with recurrence of wages and prices, wars, and the scale of industrialization; long-term conjunctures are more likely temporal changes, such as “long-term demographic movements, the changing dimensions of states and empires, the presence and absence of social mobility in a given society, (and) the intensity of industrial growth” (Braudel, 1972: 899).

The last temporal level (l’histoire évènementielle) represents history of individual persons and events which might be called the “traditional history” (Braudel, 1972: 21; Braudel, 1980: 27). He defines such a short-term history as being “brief, rapid nervous fluctuations” (Braudel, 1972: 21). He also argues that this history, which has a contrast on either side, is both the most enriched and the most dangerous (Braudel, 1972: 21). In his thesis, the Mediterranean world is at the center of events

(évènements), which record all forms of human actions, and individuals (Braudel, 1972).

9

It is worth noting that the concept and division of time in Braudel’s historical narrative is a significant milestone in the understanding of “total history” (histoire totale). Braudel emphasizes that historical narrative is neither a method nor an objective method par excellence, but rather a simple philosophy of history. In comparison to traditional divisions that cut the story of life, he suggests that his division of time is a way for a straightforward explanation from one level to another (Braudel, 1972: 21). While each phenomenon occurring in different wavelengths of time has characteristic rhythms, such as “politico-economic”, “socio-ideologic systems”, time itself does not have a pre-established content. Therefore, history is a unification of diverse times with different speeds (Bintliff, 1991: 7; Knapp, 1992a: 6).

Braudel’s “structural history”, which contains “time”, “structure”, and “agency” in time and space, offers a fresh insight for the solution of some central problems posed by some post-positivist critics of social sciences (Bintliff, 1991: 7-8; 2004).

However, there have also been some criticisms of Braudel’s paradigm. According to Hexter (1972: 533), Braudel’s paradigm fails to create a linkage between short-term and long-term. Therefore, Le Roy Ladurie, the third generation of Annales, paid more attention to events, which constitute a critical point of intersection for understanding and explaining change (cf Bintliff, 1991; 8; Knapp, 1992a: 6).

However, Braudel perceives l’histoire évènementielle (“microhistory”) beyond the narrative political history, in which the examination of diachronic historical process short-term events was temporary and were perpetual (Knapp, 1992a: 6). It seems, though, that he did this deliberately because he advocates that events can only be explained with reference to the longer-term structures (Braudel, 1972: 21). Another criticism was made on his choice of seeing essential structures of long-term and medium-term as environmental constraints, the history of demography and economic sequences that he neglected mentalités (Bintliff, 1991: 9). In fact, mentalité is

another aspect of the historical process as important as longue durée, conjoncture, and évènements. More straightforwardly, mentalité is a world of ideologies, and viewpoints, and can come into existence as a result of either individual or unified exertion (Bintliff, 2008: 158).

10

Taking into account all the facts about the Braudel paradigm, one may think what to utilize from this “philosophy of history” in archaeology. Although through the contributions of many disciplines and through the data obtained it is possible to interpret past and past societies at an interdisciplinary level, Bintliff (1991: 3) does not agree with the idea and suggests that Annales is already an interdisciplinary contributor to the discovery and analysis of the past societies. Furthermore, Annales methodology is “complementary” rather than “contradictory” in the interpretation of the past.

Not surprisingly, I will not be the first or the only person who aims to apply Braudel’s philosophy of history in archaeology. Up to the present, many

archaeologists have applied at least one temporal level3 of Braudel’s paradigm in

their own research field and era (Knapp, 1992b; Bintliff, 1991; Barker, 1991; Vallat, 1991; Jones, 1991; Ames, 1991; Foxhall, 2000; Bintliff, 2004; 2010). One cannot deny the fact that all these case studies by applying Braudel’s paradigm contributed to archaeology as a human science and encouraged many other archaeologists or students, like me.

Among the successful case studies, Graeme Barker (1991), after working for many years in the Molise and Biferno River valley (in Italy), interprets the settlement nature of this region for three main settlement eras (prehistoric, classical, and medieval settlements) according to Braudel’s paradigm. Although the prehistory of the region lacks data (ca. 4500 BC); thus, preventing évènements from being

determined precisely, it is evident that the environment (longue durée) had a decisive role in prehistoric settlements. These prehistoric communities used the lower valley for agriculture, and the middle and upper valleys for hunting and pastoral purposes. Change occurred in the 2nd millennium BC when the lower valley suffered from the water course and upper valley from a stony soil, because of which these areas were abandoned. In the first half of the 1st millennium BC, however, the settlement expanded to the limit of the upper valley’s marginality, a transformation which is associated with the population pressure (Barker, 1991: 45-46).

11

In the Classical period, there is much more evidence to be fit into Braudel’s paradigm of évènements, such as the destruction of Roman towns after the Social War. Furthermore, the increase and expansion of the population from the 5th to the 2nd centuries BC and the eventual migration of Samnite groups throughout the Apennines and Campania are the main objective for conjoncture. Another conjoncture is the investment of the Roman aristocracy for its own wealth and eventually the establishment of villa property on the land acquired by the empire (Barker, 1991: 50-51). He exemplifies mentalité with the Samnite elites who became more familiar with new lifestyles and new symbols of power after the imposition of Romanization (Barker, 1991: 51).

In another case study, Knapp (1992c) applied the Annales approach to the southern Levant between ca. 1700-1200 BC, when the social complexity increased and eventually collapsed, in order to establish continuity and change in the socio-aspect of the region. He also tried to establish the connection between short-term events and long-term structures and the “moments” of socio-cultural change in both light of archaeological and written documents. While the episodic documentary evidence of north Jordan and Jezreel Valleys constitutes the historical documentation,

archaeological patterns recovered especially from Pella in north Jordan are another source of data. As a result, while the spread of urbanization in the Middle Bronze Age accelerated both political and economic intensification, the imperialist policy of Egypt in the Late Bronze Age, as an external factor, accelerated destabilization and eventual collapse of the existing system in the region. The combination of regional (“macroscopic”) and local (“microscopic”) production helped to open the interaction (“dialectic”) between events and structures in the movement of history (Knapp, 1992c).

2.2. Discussion

All in all, it is reasonable to argue that amongst the archaeological case studies, which applied Braudel’s philosophy of history to their areas of study, two of them could be presented in order to have both a better understanding of the contribution of Annales and the applicability of Braudel’s paradigm in archaeology. Therefore, in this thesis, I will try to follow the models of Barker (1992) and Knapp (1992c) to understand the Late Chalcolithic period in north Mesopotamia.

12

CHAPTER 3

THE LC 1 AND 2 PERIODS IN NORTHEAST MESOPOTAMIA

This chapter focuses on the excavated and surveyed material culture of northeastern communities during the LC 1, LC 2 and partially LC 3 in order to understand social, economic, and political continuity and change through time. It initially starts with a brief overview of the preceding Ubaid phenomenon. At the end of the chapter, cultural continuity and change through time will be discussed within the scope of the Annales paradigm. Before moving to the subject matter of this chapter, an

explanation of terminology about late 5th - 4th millennium BC Syro-Anatolia is necessary to prevent confusions. In recent terminology, groups living in Syro-Anatolia during these periods are denominated under various nomenclatures. One of the commonly known terms is the “Local Late Chalcolithic” (Stein, 2001: 267), which refers to the indigenous communities of Syro-Anatolia in the LC 1, LC 2, and LC 3 periods. The same periods are also called the “Pre-Contact” period by some scholars (Lupton, 1996; Rothman, 2001b: 380; Erarslan & Kolay, 2005: 82; 2009: 193). It should, however, be emphasized that such a speculative term may lead to distortions in defining the “ancient reality” (Rothman, 2001b: 368). Otherwise, the term “Pre-Contact” may be implying that there was no contact between north and south Mesopotamia during the early Late Chalcolithic.

3.1. The Ubaid Phenomenon

In the long span of Mesopotamian history, the Ubaid period is generally considered to be the period when the earliest complex society in Mesopotamia began to appear gradually (Stein, 1994: 36; 1996: 27). This period, which represents also a material culture, emerged in southern Mesopotamia around the mid-6th millennium BC and continued until the 4th millennium BC (Stein, 1994: 36). In time, the cultural

13

a “T shaped” architectural plan, ceramic technology along with decoration, bent clay nails or mullers, cone head clay figurines, and clay sickles spread gradually over especially north Mesopotamia up to the Upper Euphrates and Upper Tigris basins as well as eastern Anatolia (Stein, 1994: 37). It is worth mentioning, nevertheless, that this does not mean that there was a cultural uniformity or

homogeneity among all the regions given above. Nor was it necessarily the desire of Ubaid groups to exercise domination over ‘non-Ubaid groups’. Rather, this

circulation of the Ubaid type material assemblage can be understood as a result of long-distance interaction among the local polities of both spheres (Frangipane, 2002: 170; Rothman, 2001b: 318; Stein, 2012: 128-129).

The density of the Ubaid interaction with the northern communities depended on time and space. In other words, while some areas of north Mesopotamia were located directly on the interaction network with the Ubaid culture, some were outside of this network. To give an instance, archaeological indications of the Ubaid phenomenon, particularly pottery production and architectural similarities recovered in eastern and central parts of north Mesopotamia (from the Tigris valley to the Khabur basin) are much more visible than in the west of the Balikh and the Euphrates regions (Frangipane, 2012a: 42). This thus demonstrates that the Ubaid culture had a different degree of impact on the local communities in different zones (Stein, 2010a: 24; Frangipane, 2012a: 43). Although one cannot deny the fact of the spread of Ubaid material culture and its cultural impact on the north Mesopotamian sites, recent studies have shown that the Ubaid interaction declined after ca. 4500 BC (Stein, 2012: 132). Therefore, the phase after ca. 4500 BC in chronological terminology is known as the terminal Ubaid, which is at the same time

contemporary with the LC 1 (ca. 4500-4200 BC) (Rothman, 2001a: 5-9).

3.2. Transition from Late Ubaid to the Late Chalcolithic Period

The LC 1 and LC 2 periods provide the earliest evidence for a gradual urbanization process in northern Mesopotamia, especially in the upper Khabur and Mosul areas (Stein, 2012: 139). For instance, Tell al-Hawa located in the north Jazeera area was roughly 50 hectares during the LC 1-3 periods (Ball et al. 1989:32). Recent

excavation projects conducted in the Khabur basin have shown that sites like Tell Brak were already quite substantial in size, even before the “Uruk expansion”,

14

growing in urban size from 55 ha during the LC2 to 130 ha in the LC 3 periods (Oates et al. 2007; Ur et al. 2007). A similar settlement pattern and spatially extensive site (ca. 300 ha) is also documented at Hamoukar that is identified as a “proto-urban” site between village and city during the LC 1-2 periods (Al Quntar et al. 2011: 153).

Following the Ubaid period, the LC 1 period is also a poorly known period in north Mesopotamia compared with the succeeding LC 2 and LC 3 periods (Frangipane, 2012a: 47; Stein, 2012: 132). The LC 1 period is broadly characterized as a period of economic diversity and elite development (Stein, 2012: 132) that had its roots in the preceding Ubaid period. Despite significant degrees of variabilities in north Mesopotamia during the final stages of the Ubaid period, there are, however, several changes that appear to be attested everywhere (Frangipane, 2012a: 43; Stein, 2012: 132). One of the most apparent changes is the common use of slow wheel or tournette, which accelerated the development of the mass production of standardized pottery (Frangipane, 2012a: 43).

Another shift away from mass production is from the gradual abandonment of elaborate fine and Ubaid derived painted pottery to the manufacture of unelaborated hand-made, mineral tempered bowls such as moulded flat-based bowls and round-bottomed flint-scraped bowls, the so-called “Coba bowls” (Frangipane, 2002: 174; 2012a: 43- 44; Stein, 2012: 132). They were first unearthed at Coba Höyük (Sakçe Gözü) and are typologically crude: incompletely oxidized, flat-based, simple-rim (Schwartz, 2001: 236-237). Moreover, it is suggested that the simplification of some certain elements of pottery production such as decoration and manufacture is related to a change in “social use of pottery”. In other words, while pottery in the preceding Ubaid period was a medium for expressing group identity especially in social events, in time, it lost its function which implies that communal practices became less important (Frangipane, 2012a: 44).

Having been recovered in large quantities at a number of sites in north

Mesopotamia, Coba bowls and related types are often identified as serial and mass-produced bowls; thus, denoting important cultural changes at the end of the Ubaid period (Baldi, 2012a: 394). Nevertheless, we should bear in mind that the term

15

“Coba” does not reflect that the production was in the responsibility of a single manufacture center in which only one form of bowl from the same component was produced and circulated across the entire north Mesopotamia. Rather, it represents regional diversities across the northern Mesopotamian sites, as attested by round-based, flat-round-based, chaff-tempered, and grit-tempered examples with a scraped bottom (Figure 2) (Balossi-Restelli, 2012a: 240).

3.3. LC 1-2 periods in northeast Mesopotamia 3.3.1. Iraqi Jazeera

The first area to be mentioned is eastern Jazeera encompassing roughly modern Mosul, Erbil, and Kirkuk, in northern Iraq (Figure 3). The number of sites occupied in the LC 1 period is fairly scarce in this region, particularly dispersed around agricultural lands, although several settlements such as Tepe Gawra and Shelgiya are in the foreground in each area. The general characteristic feature of the sites dating to this period is their small size (Rothman, 2001b: 378). The ceramic assemblage shows that the increasing number of plain Chaff Faced Ware (CFW hereafter) was prevalent in these regions. In contrast with the Ubaid period, there is a gradual abandonment of decorated ware apart from Sprig Ware bowls and jars. The other diagnostic types include U-shaped vessels and footed bowls (Rothman, 2001b: 371-373; Lupton, 1996: 17).

Tepe Gawra located on the east of the Tigris River is one of the best-understood

sites during the LC 1-3 periods in eastern Jazeera (Figure 3) (Rothman & Blackman, 2003: 5). The site is defined as a small center not more than 1.5 ha during the LC 1-3 periods (Rothman, 2002; Rothman & Blackman, 2003: 5). At Tepe Gawra, Level XII provides significant amounts of data for socio-economic life in the LC 1 period. At the site were multifunction buildings which combined

different spaces for daily practices: craft production; the domestic architecture for the extended families (tripartite planned); ritual areas and a series of storerooms. There are also archaeological indications of far-flung material exchange such as obsidian probably from the Van region, lapis lazuli from Badakshan, gold objects from the Taurus, marble, granite, chlorite, and copper (Rothman, 2002: 81;

16

Sprig Ware jars and bowls, Wide Flower pots with extended bases, U-shaped vessels, which were used for burials, and footed bowls (Tobler, 1950: 148; Rothman, 2001b: 371-73; Rothman & Blackman, 2003: 6).

In the broader frame, the ceramic assemblage also demonstrates that the far-flung exchange was not only restricted to exotic or precious materials given above but also some pottery types. Especially Sprig Ware seems to be used as a material of exchange, as Sprig Ware was recovered also from Shelgiyya, identified as the manufacturing center for painted wares (Rothman & Blackman, 2003: 14), west of the Tigris and at Tell al-Hawa located in north Jazeera (Rothman, 2001b: 379-380), as well as at Hamoukar in Syrian Jazeera (Ur, 2002a: 18). Similarly, in the further north area of the Tigris River valley, the Cizre plain located east of the Tigris River, produced Sprig Ware rims at two sites, Gire Tahti and Revini South within the survey project (Algaze et al. 2012: 92-93). There are also examples at Türbe Höyük, 2 km north of the confluence of the Bohtan river and at Başur Höyük, 20 km west of modern Siirt (H. Sağlamtimur, personal communication, November 4, 2017). In comparison with the northern valley, no Sprig Ware sherds were recovered during the survey conducted around Helawa in the Erbil plain (Figure 3) (Peyronel and Vacca, 2015: 111).

According to Lupton (1996: 17), 10% of the ceramic repertoire of Tepe Gawra level XII consisted of Sprig Ware, which was also recovered from a handful of sites in the North Jazeera Project (NJP) (Wilkinson & Tucker, 1995). Thus, Lupton

interprets Sprig Ware “as a status item” because of its rarity. It seems, however, that Sprig Ware would not have been a status mark; rather it could have had a special function to explain its rarity. Furthermore, the other precious materials such as gold and lapis lazuli recovered from level XII at Tepe Gawra show that such imported materials were not as common as the pottery; therefore, the presence of truly exotic and precious materials reduces the possibility that pottery was a “status item”.

In the subsequent LC 2 period, the number of sites and the quality of evidence increased especially along the Khazir Su and the Tigris River. New sites like Musharifa and Nineveh came into existence. It should be noted that there is some speculation about Nineveh. In fact, the characteristic pottery of the LC 2 period was

17

not recorded at Nineveh, perhaps because of the prehistoric levels’ limited exposure in small and deep soundings (Rothman, 2001b: 380-381). Rothman (2009: 23), nevertheless, concludes that Nineveh was not occupied in the transition period from the terminal Ubaid to the LC 1 and even early LC 2 periods.

Tepe Gawra in the early LC 2 period (Level XI A/B) seems to retain similar

architectural features except for a spectacular building, the so-called “round house” (Rothman & Peasnall, 1999: 109). Its function has been a subject of considerable debate (e.g. temple and silo: see also Rothman & Blackman, 2003: 6-9): the spatial distribution and the materials recovered in the building including domestic artifacts, mace head, gaming pieces, and serving vessels give the impression that it had either a military function (Rothman & Blackman, 2003: 8) or a living quarter for people who had higher status associated with their activities (Rothman, 2002: 92). The other private houses are smaller, mostly comprising one or two-room buildings. The material assemblage indicates that as was the case for the preceding period,

residents continued to “import” or “obtain” highland resources. In addition, in this level, there is the physical evidence of cloth-making, woodworking, and ceramic firing facilities (Rothman & Blackman, 2003: 9). The pottery repertoire of Tepe Gawra in the LC 2 period consists of stamped and applique wares, early Wide Flower, carinated tumblers, double or channel rim bowls, double spouted jars, gray, lightly burnished vessels, hole-mouth jars, and bowls with cannon spouts (Rothman, 2001b: 372-73).

Another site that has LC 2 period content is Qalinj Agha (levels I-V) covering some 3.3 ha and located 1.5 km south of the citadel of Erbil (Figure 3). The remains of level I are thin walls, floors, ovens, and kilns that are poorly preserved. In level II, however, several domestic structures along with a pottery workshop and several infant jar burials have been excavated (Peyronel & Vacca, 2015: 96-97). A large tripartite structure that was termed the “Western Temple” due to its tripartite plan and offering tables in the central room, as well as female figurines found in the adjoining room, was excavated in level III (Lupton, 1996: 33; Peyronel and Vacca, 2015: 98). This type of architectural plan has parallels at Gawra XII-XI and Telul eth-Thalathat II (Peyronel & Vacca, 2015: 98). Painted decorations in the central

18

room may also suggest that the building fulfilled a special function, which according to Lupton (1996: 33) cannot be a ‘temple’; rather a substantial elite residence.

Similarly, in the following phase, two tripartite buildings had presumably the same function. Of these two buildings, one has a T-shaped central room, suggesting that such tripartite planned structures have their root in the preceding Ubaid period (Peyronel & Vacca, 2015: 98) The pottery assemblage consists of red-slipped and gray wares, and other level II materials are clay animal figurines and clay objects: the so-called “eye idols” and double horned objects. A spectacular category of finds are the infant jar burials, which contained a variety of precious and exotic materials such as gold beads and an obsidian spatula decorated with gold (Lupton, 1996: 32).

Located south of Jebel Sinjar, Grai Resh is another site from which LC 2 period archaeological materials were recovered in levels IV, III, and IIB (Figure 3).

According to 14C samples, Level IV is the earliest phase dating to ca. 4250-4150 BC, followed by subsequent Level III (4150-4050) and Level IIB (4050-3850) (Kepinski, 2011: 51). Although no consistent structural elements were identified, the ceramic remains of levels IV mainly consist of Red Burnished Ware, Reserved Slip Ware and Brown Slipped Ware sherds.

In level IIB, luckily, several tripartite buildings, silos for storage, and ovens for cooking were excavated. One of these tripartite buildings has an oblong adjoining room which was used as a bead workshop, where hundreds of beads of calcite, bone, shell, flint, and obsidian were found. Moreover, a seal made of black stone and an amulet in the form of a human head in profile came from the same room. It is suggested that having both tripartite plan structure together with the workshop room bears similarities with the building found in level IX at Tepe Gawra (Kepinski, 2011: 56).

In another area of level IIB, numerous ovens both inside and outside of several buildings were also found. Those buildings contained flint and obsidian tools, such as mortars, grinding stones, hammers, and spindle whorls. Away from the tripartite buildings, the abundance of ovens and silos along with many tools may indicate that this quarter of the settlement had an entirely domestic function (Kepinski, 2011: 58).

19

None of the Sprig Ware and Incised-Impressed Pottery have been recorded.

However, the CFW Coba bowls are attested in levels IIB and III. In addition, angle neck jars, and hole-mouth pots were found in level IIB (Kepinski, 2011: 58-59). The overall evidence from Grai Resh suggests that the site was a local center in which long distance contacts and exchanges took place during the period between ca. 4200 and 3850 BC (Kepinski, 2011: 70).

The second area of study is the north Jazeera plain that stretches between the modern eastern border of Syria and the east bank of the Tigris River on the west-east axis (Figure 1). The plain is almost devoid of both natural and mineral sources. None of the desirable raw materials such as copper, bitumen, basalt, salt, flint, and limestone are available in this region (Wilkinson & Tucker, 1995: 6). A total of 66 sites ranging from 0.3 to 5.8 ha in size have yielded pottery sherds dating to LC 1-2 and 3 periods. Amongst the surveyed sites, Tel al-Hawa was the dominant site in the plain covering an estimated 50 hectares (Figure 3) (Ball et al. 1989:32). Based on the pottery sherds surveyed in the plain, sites situated particularly at the center of the plain continued into the subsequent LC 4 and 5 periods (Wilkinson & Tucker, 1995: 125-134; Lupton, 1996: 26).

Even though Tell al-Hawa is suggested to be ca. 50 ha, the total area excavated for the LC 1-2 periods is only a small sounding (trench LP) (Ball et al. 1989: 31). It should be stressed, therefore, that the exceptional 50 ha scale of Tell al-Hawa may be misleading and the LC 1-2 phases may not have extended over the entire site, as there are no complete architectural remains identified. The pottery assemblage recovered from the sounding is predominantly plant tempered for the earlier periods including shallow bowls and steep-sided deep bowls (Ball et al. 1989: 39). For the earlier 4th millennium BC, hole-mouthed jars have parallels with Tepe Gawra levels XI-IX and Grai Resh levels II-IV in the Sinjar area (Ball et al. 1989: 40; Lupton, 1996: 17). Apart from the pottery assemblage, a burnt clay sealing with a stamp seal impression (Ball et al. 1989: 39), has parallels with Tepe Gawra, Qalinj Agha and Norşuntepe seals (Lupton, 1996: 28).

In the further northeast of Jazeera, where LC pottery assemblage was collected, the area located north of Nineveh has been recently surveyed within the scope of the

20

“Land of Nineveh Project” (Gavagnin et al. 2016). The LC pottery repertoire of the surveyed area is characterized majorly by hand-made, undecorated inwardly beveled rim bowls that were also recorded at Hamoukar, Tepe Gawra, Nineveh, Tell Brak and Hacinebi Phase A. These bowls occasionally have red and brown painted decorations that also show a widespread distribution from the east Jazeera as far as the Keban area, suggesting a long-distance contact (Gavagnin, et al. 2016: 128).

3.3.2. The upper Tigris Basin

The upper Tigris Valley located in the southeast of Turkey covers an extensive area and is geographically surrounded by mountains (Figure 1). This geographical isolation gives rise to several distinctive ecological niches in the valley (Brancato, 2017: 17).4 Having rich and fertile lands for agriculture, the valley has the three

major tributaries of the Tigris River: the Bohtan Su, Garzan Su, and Batman Su. These by themselves not only increase agricultural productivity in the valley but also are the main area for settlements. Ancient settlements, just like the modern

occupations, were mostly situated near river or stream beds (Brancato, 2017: 19). This demonstrates that rivers were the main source of water as well as the

communication network. Located close to the Taurus range, people living in the valley not only had easy access to the essential raw materials, such as wood, and stone, but also had access to the mineral sources (Ökse, 2015a: 17). Especially, Ergani-Maden (30 km north of Diyarbakır) was a main area for copper procurement as early as the LC period (Gale, 1991; Yakar, 2002; Wagner & Öztunalı, 2000: 55-56; Amzallag, 2009; 499, Table 1).

Our archaeological knowledge of the upper Tigris valley is very little and recent compared with other regions of north Mesopotamia (Bernbeck et al. 2004; Bernbeck & Costello, 2011; Parker & Foster, 2009). The archaeological investigations in the valley have been done intensively in the last three decades within the scope of survey projects and salvage excavations. Throughout numerous survey projects carried out in the valley, at least 700 archaeological sites have been documented (Brancato, 2017; Algaze, 1989; Algaze et al. 1991; Ay, 2001; Peasnall, 2004; Peasnall &

4 The upper Tigris Valley on the north (southern Taurus) and northeast is surrounded by upland areas,

and to the south by the Mardin mountains. Moreover, the Karacadağ massif in the west separates the upper Tigris Valley (modern Diyarbakır) from the Harran plain (east of Şanlıurfa). Consequently, such physical barriers create several ecological niches in the region (Ökse & Görmüş, 2006: 167).

21

Algaze, 2010; Ökse, 2013; Ökse et al. 2009; Algaze et al. 2012; Laneri et al. 2008; Ur & Hammer, 2009; Erim-Özdoğan & Sarıaltun, 2011). It can, however, be argued that despite a significant number of the sites (61 sites), in which there is the LC period content (Brancato, 2017: 55), only some of them could be excavated because of time constraints.

Of the excavated sites, Yenice Yanı is a small settlement covering some 1.2 ha and located along the eastern bank of the Seyhan Çay, roughly 10 km southeast of Bismil, in Diyarbakır (Figure 3). Based on the second surface collection, the site has tentatively been dated to the LC period (Bernbeck et al. 2004: 117). In contrast with many LC sites, especially those located in the Euphrates valley and investigated magnificently because of the Uruk phenomenon, the Yenice Yanı excavations were significant in relating its local marginal features to the LC in this region, and to assess whether it experienced longer-scale impacts (Bernbeck et al. 2004: 117; Bernbeck & Costello, 2011: 654).

The LC period sequences (LC 1, 2, and 3) were followed in two areas in small step trenches known as Unit A, lower slope of the mound and Unit B as the upper slope of the mound (Bernbeck et al. 2004). On the basis of the relative chronology of ceramic materials, a proposed dating for the LC ranges between ca. 4300-3700 BC (Bernbeck et al. 2004: 120). According to site chronology, the Yenice Yanı 5 (“YY 5”) phase corresponds to LC 1 and can be identified in phases IV-III (Unit A) and phases VII-VI (Unit B).

It is suggested that phase VI with high artefact density may consist of a household debris. A carbon sample taken in this area dated this phase to 4500-4340 BC (Bernbeck & Costello, 2011: 657). On the other hand, phase V is represented by a possible food preparation area, as there are several thick pebble surfaces, a large basalt grinding stone and a smashed cooking vessel (Bernbeck et al. 2004: 118). In addition to stone and obsidian tools (Bernbeck & Costello, 2011: 664, table 4), several conical loom weights, some of which were decorated elaborately, indicate that textile production took place at Yenice Yanı in the second half of the 5th

22

is mainly hand-made or slow wheel-made including both diagnostic Ubaid painted sherds and Coba bowls (Bernbeck et al. 2004; 118; Bernbeck & Costello, 2011: 658).

The LC 2 period (YY 4) is identified in Unit B (phases V-IV) and does not have an equivalent in unit A (Bernbeck & Costello, 2011: 657). In phase B V, the decreasing quantity of painted sherds and Coba bowls and the increase in hammerhead bowls, casseroles, and Coarse Brittle wares suggests a date between the late LC2 or early LC 3 period (Bernbeck et al. 2004: 119-120; Bernbeck & Costello, 2011: 659). Therefore, the subsequent phase IV, with examples of Coarse Brittle ware associated with LC 3 hammerhead bowls and casseroles, can be clearly dated to the LC 3 period (Bernbeck et al. 2004: 118).

At Salat Tepe, another site located on the northern bank of the Salat Çay, LC sequences were identified in step trenches situated in the southern slope of the mound (Figure 3) (Ökse, 2005: 785-788, fig. 7; Ökse, 2008: 683-684; Ökse & Görmüş, 2006: 186; Ökse & Görmüş, 2013a: 163-166). The LC period is characterized by hand-made and chaff-tempered like CFW, Chaff-Faced Simple Ware, Chaff/Straw Tempered Ware together with Painted Ware (Ökse & Görmüş, 2006: 186). LC period stratigraphic sequences of the site relevant to this discussion are IB (ca. 5200-4100 BC), early IC (ca. 4200-3600 BC) (LC 2-3), and late IC (ca. 3600-3300 BC) (LC 4) (Ökse & Görmüş, 2013b: 93; Ökse, 2015b: 16-18; Ökse, 2017: 43, fig. 3-3).

Period IB consists of multiple levels of the characteristic tripartite mudbrick structures that are mostly considered the Ubaid hallmark (Ökse et al. 2014: 118; Ökse et al. 2015: 22; Ökse, 2017: 43). In addition, there are quadrangular storage units that must have been used as pottery workshops (Ökse et al. 2012: 180; Ökse & Görmüş, 2013b: 93; Ökse, 2012: 8; Ökse, 2015b: 18) resembling Mesopotamian contemporaries (Ökse, 2012: 8).

The pottery assemblage recovered from these levels is mainly plant-tempered and comprises coarse grit-tempered funnel-necked jars, chaff-tempered flint scraped vessels (Coba), inwardly rimmed sherds that have equivalents at Hammam et-Turkman VI-VB and Tepe Gawra XI-XA, and painted vessels (Ökse, 2015b: 18).

23

The structures together with this ceramic assemblage suggest that this period can be dated ca. 5200-4400 BC (Ökse, et al. 2012: 180-181; Ökse, 2015b: 18; Ökse, 2017: 43-44).

The lower level of the same area is represented by plant-tempered and inwardly rimmed sherds, bodies with thickened rim bowls, and ovoid pots. In addition to pottery, small finds included baked clay beads, a stone axe, a grinding stone, obsidian and chipped stone blades, and a baked clay blowpipe (Ökse et al. 2013: 369-370), a very spectacular copper artefact (Ökse et al. 2014: 118) and a limestone stamp seal (Ökse et al. 2015: 22). A proposed date for the copper finding is the first half of the 5th millennium BC (T. Koizumi, personal communication, March 8, 2018).

In another area of the excavation, there was much evidence for continuous renovation of buildings, indicated by mudbrick walls built on top of each other multiple times, and rectangular plastered pits. The pottery recovered from this area is mainly funnel-shaped jars, a few Coba bowls, and combed ware sherds, suggesting a date between ca. 4400-4100 BC (Ökse, 2015b: 18). It is worth claiming, though, that the pottery type of this period seems to evolve through time, while similar

architectural layouts with multiple renovations appear to remain the same. This may demonstrate that the community of Salat Tepe remained in these traditional contexts over many generations (T. Ökse, personal communication, February 26, 2018).

Period IC (ca. 4000-3500) (LC 2-3) consists of multiple renovated phases, and walls without stone foundation indicate similar construction techniques. In this phase, several quadrangular storage units were associated with the buildings (Ökse, 2017: 44). There is also a potter’s workshop with an oval pottery kiln found in the lower level. This kiln has parallels at Tell Kosak Shamali (Post-Ubaid period) and at Değirmentepe (Late Ubaid period) (Ökse, 2012: 8). The pottery of this level consists of chaff-tempered monochrome and painted vessels dating to LC 2-3 periods and Coba bowls (Ökse & Görmüş, 2013b: 93; Ökse, 2015b: 18). In another area, there are 3 LC layers in which several mudbrick storage units were excavated. While the initial layer’s storage plan is rectangular, the upper layers turn into an elliptical plan

24

(Ökse & Görmüş, 2013a: 164). Small findings recovered from the LC levels are Canaanite blades and two grinding stones (Ökse et al. 2015: 22).

Located within the boundaries of Bakır village, in Siirt, Başur Höyük5 is another site where LC 2-3 materials were excavated in the southern and southeastern areas of the mound (Figure 3) (Sağlamtimur & Kalkan, 2015: 57-58). The site situated just on the west bank of the Başur Stream, which runs from the Bitlis Valley and flows into the Bohtan River, has fertile and well-watered agricultural lands in the immediate vicinity (Sağlamtimur, 2012: 121; Sağlamtimur et al. forthcoming).

Although a few Coba bowls, characteristic of the LC 1 period, were documented, no informative architectural remains were found (Sağlamtimur & Ozan, 2013: 514-515); therefore, it is thought that the site was re-occupied only in the final stages of the LC 1 period (Sağlamtimur et al. forthcoming). In the southeast area of the mound, two layers of the earliest LC 2 levels with square or rectangular plans were identified: a rectangular structure with a small storehouse followed by a rectangular building with a storage vessel (Sağlamtimur, 2012: 128-129; Sağlamtimur & Ozan, 2013: 515; Sağlamtimur et al. forthcoming).

The diagnostic pottery assemblage of the LC 2 period at Başur Höyük is plant-tempered and hand-made and shows continuity in to the LC 3 period. Some of the distinguishing forms of the LC 2 pottery are ‘blob paint’ bowls that were also

identified at Norşuntepe, Korucutepe, Tepe Gawra, Nineveh, Tell Hamoukar, as well as hole-mouth jars and spherical-body jars (Sağlamtimur & Kalkan, 2015: 59). In addition to plant-tempered wares, a few sand, lime and grit tempered samples are attributed to the Ubaid tradition. The close similarity of type, shape, and decoration at Tepe Gawra XI-IX, Hamoukar Phase 3-1, Tell Feres levels 6-4, Hammam et-Turkman VA, Tell Brak and Tell Leilan corroborates the cultural interaction among the regions (Sağlamtimur & Ozan, 2013: 516; Sağlamtimur & Kalkan, 2015: 59; Sağlamtimur et al. forthcoming).

5 Situated on a tributary of the Tigris River, Başur Höyük remains outstanding, as we have limited

archaeological knowledge of the Local Late Chalcolithic and “Uruk influenced” settlements along the Tigris River, unlike sites located along the Euphrates like Hassek Höyük, Hacınebi, Arslantepe, Habuba Kabira, Jebel Aruda, and Sheikh Hassan (Sağlamtimur & Ozan, 2013: 514; Sağlamtimur & Kalkan, 2015: 57-58)

25

In the following LC 3 period, the building plans and construction technique were partially changed. In this layer, in addition to several infant jar burials underneath the floor, several rectangular planned and multi-roomed spaces with thinner walls were uncovered (Sağlamtimur, 2012: 128-129; Sağlamtimur & Ozan, 2013: 515;

Sağlamtimur et al. forthcoming). The pottery of the LC 3 period is mostly plant-tempered and consists of various types including pots, bowls, flint-scraped ware, shallow bowls, casseroles, hammer head bowls and plates (Sağlamtimur et al. forthcoming). Especially casseroles together with hammer head bowls and plates are the most common pottery forms of the LC 3 period across north Mesopotamia (Frangipane, 2012a: 44; Lupton, 1996; Stein, 2012: 140).

3.4. Discussion

The settlement distribution of sites for this period is mainly concentrated near rivers and streams, suggesting that water courses were not the only place for arable and fertile lands or grazing but also the major routes for possible contact and exchange, which increased material exchange among the sites. This explains why sites

especially those located in Iraqi Jazeera have various non-local materials such as gold objects, obsidian and marble in addition to indigenous ubiquitous pottery forms such as Sprig Ware, and Wide Flower Pots. Consequently, while longue durée can be best exemplified by the wide distribution of prominent materials via water courses, the increase in the number of settlements located in Iraqi Jazeera suggests a

population increase as a long term conjoncture. The comparable examples of clay sealings and seal impressions at Tepe Gawra, Tell al-Hawa, Qalinj Agha, Tell Brak, Hacınebi, and Norşuntepe suggests a shared mentalité among these sites, although these tools must have had functionally different use attached on them in any individual site. It seems that, on the other hand, several aspects attributed to the Ubaid culture, such as pottery and architectural plan continued to be used to a varying extent in the LC period together with the indigenous materials, especially in Iraqi Jazeera. The adoption of the tripartite plan of Ubaid type seems to be served as living space at Tepe Gawra, Grai Resh, and Qalinj Agha. Unlike the Iraqi Jazeera, the Upper Tigris basin shows a more elementary style in architecture, mostly rectangular or quadrangular plans and remained mostly unchanged socio-economically in the LC 1-2.