DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION

ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING PROGRAM

THE IMPACT OF RAISING AWARENESS ABOUT

REASONING FALLACIES ON THE DEVELOPMENT

OF CRITICAL READING

PHD DISSERTATION

BY Mehmet BARDAKÇI Ankara May, 2010DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION

ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING PROGRAM

THE IMPACT OF RAISING AWARENESS ABOUT

REASONING FALLACIES ON THE DEVELOPMENT

OF CRITICAL READING

PHD DISSERTATION

BY

Mehmet BARDAKÇI

Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Abdulvahit ÇAKIR

Ankara May, 2010

i

jürimiz tarafından İngilizce Öğretmenliği Ana Bilim Dalında Doktora Tezi olarak kabul edilmiştir.

Adı Soyadı İmza

Üye (Tez Danışmanı):... ... Üye : ... ... Üye : ... ... Üye : ... ... Üye : ... ...

ii

I wish to acknowledge with special thanks and appreciation a number of individuals who provided assistance with this study as well as in my life as a graduate student at Gazi University.

It has been my honour to work with my respectful committee members. I am grateful to have been able to work with my advisor, Prof. Dr. Abdulvahit Çakır, who has provided invaluable suggestions on my study. I would also like to thank to the other members of my committee, Assist. Prof. Dr. Abdullah Ertaş, Assist. Prof. Dr. Nurdan Özbek Gürbüz, Assist. Prof. Dr.Paşa Tevfik Cephe and Assist. Prof. Dr. Neslihan Özkan. I am grateful for their challenging, professional and supportive encouragement as well as their attention to details.

I am also indebted to Gonca Ekşi for her kindness in applying this study in her classes.

I also wish to thank my colleague Egemen Aydoğdu without whose help the analysis of this study would not have been possible.

I am blessed to have such wonderful friends; K. Dilek Akpınar, Selmin Söylemez, M. Serkan Öztürk, Ceylan Yangın Ersanlı and Deren Yeşilel, whose support always gave me strength.

My deepest love and gratitude go to my wife, Gül Senem Bardakçı, and children for their patience and never-ending support during my study.

Finally, I would like to thank all of my participant students for their time and effort in the collection of the data.

iii

MUHAKEME YANLIŞLARI HAKKINDA FARKINDALIK YARATMANIN ELEŞTİREL OKUMA GELİŞİMİ ÜZERİNE ETKİSİ

BARDAKÇI, Mehmet

Doktora, İngilizce Öğretmenliği Bilim Dalı Tez Danışmanı: Prof. Dr. Abdulvahit ÇAKIR

Mayıs-2010, 156 sayfa

Günümüzde hızla gelişen teknoloji sayesinde hayatımızın neredeyse her anında argümanlarla kuşatılmış durumdayız. Reklam şirketleri, satış elemanları ve politikacılar bazı argümanları sanki gerçekmiş gibi sunarak bizleri ikna etmeye çalışmaktadırlar. Bizleri ikna edebilmek için sözcüklerle oynamayı ve duygulara hitap eden söylemleri kullanmayı ve aynı zamanda muhakeme hatalarını da kullanmayı çok iyi bilmektedirler. Hatiplerin ve yazarların gerçek niyetlerini ortaya çıkarabilmek için gözümüzü açık tutmalı ve sorgulayıcı bir düşünce tarzı geliştirmeliyiz.

Bu çalışmanın amacı muhakeme yanlışları hakkında farkındalık yaratmanın Gazi Eğitim Fakültesi, İngilizce Öğretmenliği Anabilim Dalı birinci sınıf öğrencilerinin eleştirel okuma becerileri üzerine etkisini incelemektir. Bu etki, çalışmada kullanılan her bir muhakeme yanlışı için 7 tane soru içeren, 56 soruluk muhakeme yanlışları testi ile değerlendirilmiştir. Literatürde, 14 ile 191 arasında değişen birçok muhakeme yanlışı olmasına rağmen bunların hepsi çalışmaya dahil edilmemiş, sadece testte geçen ve sık karşılaşılanlar tercih edilmiştir. Bunların yanı sıra, literatür çalışması esnasında bazı sık karşılaşılan muhakeme yanlışları da belirlenerek literatür taraması bölümüne dahil edilmiştir. Bu çalışma, argümanları ve tartışma yazılarını sorgulama üzerine eğitim alan öğrencilerle geleneksel okuma sınıflarında normal müfredatı takip eden öğrencilerin muhakeme yanlışları hakkındaki farkındalıklarını karşılaştırmaktadır.

Veri toplama aracı olarak ön-test ve son-test kullanılan gerçek deneysel araştırma deseni kullanılmıştır. Elde edilen veriler bağımsız değişkenler t-testi, Wilcoxon işaretli sıralar testi ve Mann-Whitney U-testi ile analiz edilmiştir. Deney grubu 27, kontrol grubu ise 24 öğrenciden oluşmuştur. Gruplar, on şube arasından rastgele yöntemle seçilmiştir.

iv

öğrencilerin, eleştirel okuma becerilerini muhakeme yanlışlarını öğrenerek geliştirebilecekleri sonucuna varılmıştır. Çalışmayla ve çalışmanın sonuçlarıyla paralel olarak bazı sınıf içi uygulamalar tartışılmış ve daha sonraki çalışmalar için önerilerde bulunulmuştur.

Anahtar kelimeler: İngiliz Dili Eğitimi, Eleştirel Muhakeme, Muhakeme Yanlışları, Muhakeme Yanlışları Öğretimi, Eleştirel Okuma

v

THE IMPACT OF RAISING AWARENESS ABOUT REASONING FALLACIES ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF CRITICAL READING

BARDAKÇI, Mehmet

PhD Dissertation, English Language Teaching Program Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Abdulvahit ÇAKIR

May-2010, 156 pages

Today, with the fast growing technology, we are surrounded with arguments in almost every moment of our lives. The advertising companies, salesmen, and politicians etc. try to persuade us by exposing some arguments as facts. They know how to play with semantics and how to use emotive language, and also they know how to use these fallacies to persuade us. To unearth the real intention of the speakers or writers, we should be alert and develop a questioning mind.

The aim of this study was to explore the impact of raising awareness about reasoning fallacies on the development of critical reading skills of the first year students in the ELT department, Gazi Faculty of Education. It was evaluated via a 56-question reasoning fallacies test confining seven questions to each fallacy studied in this research. Although there are numerous kinds of fallacies, between 14 and 191 to be more precise, the common ones were chosen in accordance with the reasoning fallacies test for practical reasons. In addition to this, during the literature review, some other common fallacies were determined and included in this dissertation. This study compared the students trained explicitly about questioning the arguments and argumentative texts on the one side and the students in the ordinary reading classes following the regular syllabus in terms of awareness about reasoning fallacies.

A true experimental design was used to collect data through pre- and post-tests. The collected data were analyzed by using independent samples t-test, Wilcoxon signed-ranks test and Mann-Whitney U-test. The experimental group consisted of 27 students and the control group consisted of 24 students. The groups were randomly selected from among ten classes.

vi

(p<0, 01). According to the results, it can be concluded that students can improve their critical reading skills through learning how to determine reasoning fallacies. In accordance with the study and its results some implications were discussed and some suggestions were made for further research.

Key words: English Language Teaching, Critical Reasoning, Reasoning Fallacies, Teaching about Fallacies, Critical Reading

vii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS...ii

ÖZET ...iii

ABSTRACT... v

TABLE OF CONTENTS... vii

LIST OF TABLES... xi

LIST OF FIGURES ...xii

CHAPTER 1 ... 1

INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 Background to the Study... 1

1.2 The Purpose of the Study ... 2

1.3 Research Questions ... 4

1.4 Limitations of the Study... 4

1.5 Definition of Some Key Concepts ... 5

CHAPTER 2 ... 7

REVIEW OF LITERATURE ... 7

2.0 Introduction ... 7

2.1 Nature and Dynamics of Language... 7

2.1.1 Forms and Functions of Language ... 9

2.1.2 The Construction of Meaning... 10

2.1.2.1 Cognitive and Emotive Meaning ... 14

2.1.2.2 Ambiguity ... 15 2.1.2.2.1 Lexical Ambiguity ... 16 2.1.2.2.2 Grammatical Ambiguity... 16 2.2 Critical Thinking ... 18 2.2.1 Cognitive Operations... 20 2.2.2 Dispositions ... 23

2.3 Reasoning and Arguments ... 25

2.3.1 Deductive Reasoning... 26

2.3.2 Inductive Reasoning ... 27

2.3.3 Critical Reasoning ... 28

viii

2.3.5.1 Recognizing Arguments ... 32

2.3.5.2 Evaluating Arguments ... 34

2.4 Reasoning Fallacies... 36

2.4.1 Taxonomy of Fallacies ... 37

2.4.1.1 The Appeal to False Authority... 38

2.4.1.2 Either-Or Fallacy ... 40

2.4.1.3 Hasty Generalization Fallacy... 41

2.4.1.4 Self-Contradiction... 42

2.4.1.5 Appeal to Common Practice ... 43

2.4.1.6 Part-Whole Fallacy ... 44

2.4.1.7 Stereotyping Fallacy ... 45

2.4.1.8 Sexism Fallacy... 46

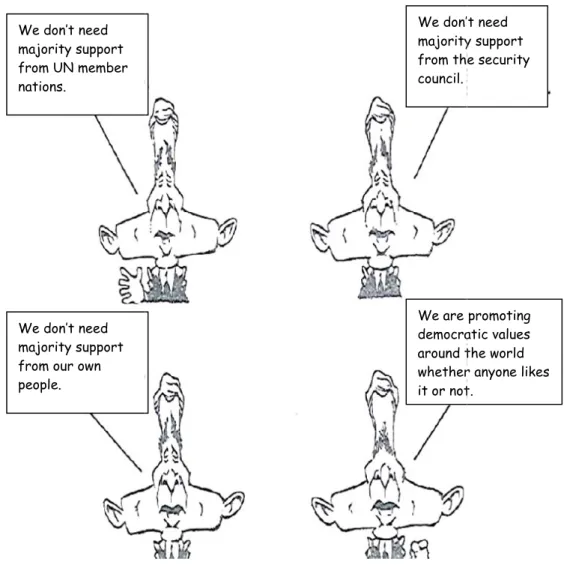

2.4.1.9 The Appeal to Emotion... 47

2.4.1.10 The Appeal to Pity (argument ad misericordiam) ... 48

2.4.1.11 The Appeal to Force ... 49

2.4.1.12 The Argument against the Person (argument ad hominem) ... 50

2.4.1.13 False Cause (argument non causa pro causa) ... 51

2.4.1.14 Red herring Fallacy (changing the topic) ... 51

2.4.1.15 Complex Question ... 52

2.5 Critical Reading in Argumentative Texts ... 53

2.5.1 The Tools of Critical reading ... 55

2.5.1.1 Analysis ... 55 2.5.1.2 Inference ... 57 CHAPTER III ... 59 METHODOLOGY ... 59 3.0 Introduction ... 59 3.1 Research Design... 59

3.2 Universe and Sampling ... 60

3.3 Instruments... 61

3.4 Procedure and Treatment ... 63

ix

4.0 Introduction ... 67

4.1 Analysis of the Pre-test Scores... 67

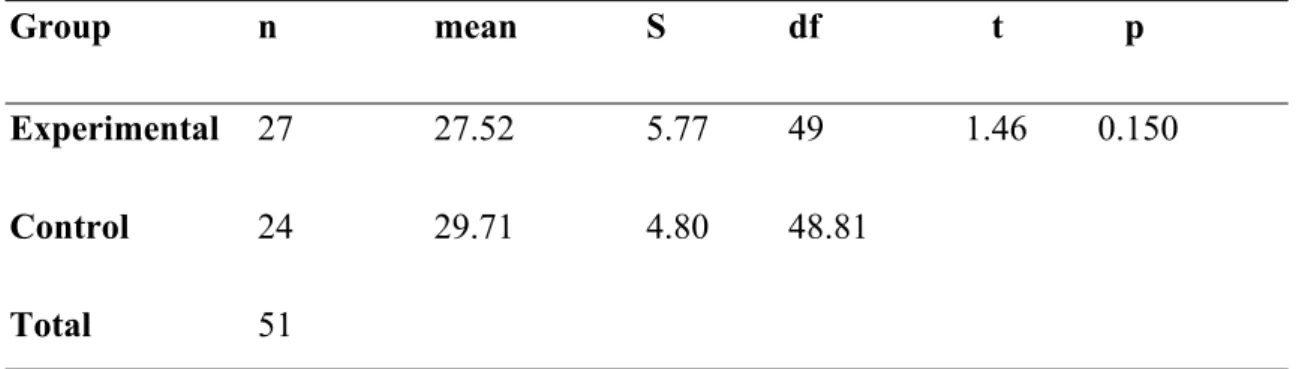

4.1.1 Independent samples t-test analysis of the pre-test scores ... 68

4.1.2 Independent samples t-test analysis of English-Turkish pre-test scores ... 68

4.2 Comparisons of Pre and Post-test Scores... 69

4.2.1 Wilcoxon signed ranks test results of the control group ... 69

4.2.2 Wilcoxon signed rank test results of the experimental group ... 70

4.3 Comparison of the experimental and control groups’ post test scores... 71

4.4 Comparison of Post-test Scores in terms of Genders... 71

CHAPTER V ... 75

CONCLUSION... 75

5.0 Introduction ... 75

5.1 Summary of the Study... 75

5.2 Pedagogical implications ... 77

5.3 Implications for further research... 78

REFERENCES ... 80

APPENDICES ... 90

Appendix I. English form of pre/post-tests ... 91

Appendix II. Turkish form of Pre-test... 110

Appendix III. Translation Team and Editor... 127

Appendix IV. Answer Sheet ... 128

Appendix V. Answers of The Reasoning Fallacies Test... 129

Appendix VI. Task I... 130

Appendix VII. Pre-Activities for Task 1... 131

Appendix VIII. Identifying F/O in a Paragraph ... 132

Appendix IX. Task 2 ... 133

Appendix X. Identifying Premises and Conclusions ... 134

Appendix XI. Task 3 ... 137

Appendix XII. Identifying the Fallacies (Appeal to Authority and Either-or) ... 138

Appendix XIII. Pre-Activity ... 139

x

xi

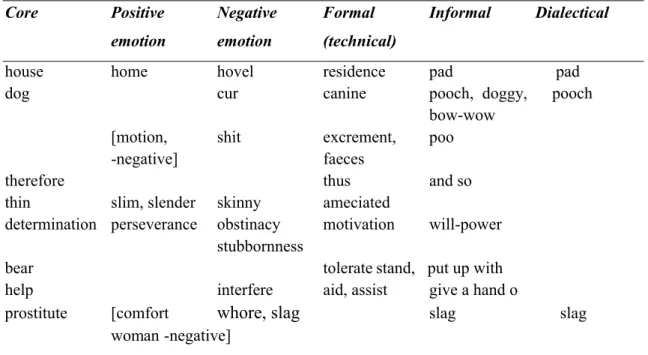

Table 1: Stylistic variations in vocabulary ... 15

Table 2: Consensus list of cognitive skills and sub-skills ... 22

Table 3: A critical approach to reading ... 54

Table 4: Narrative genres in the classroom ... 56

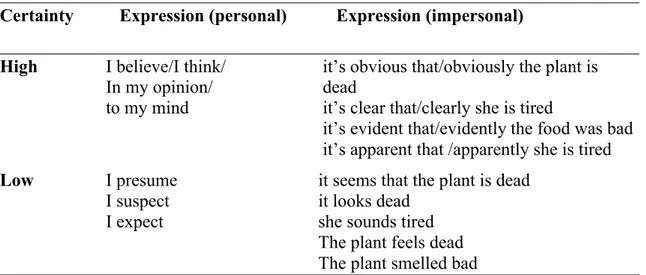

Table 5: Markers of subjectivity... 57

Table 6: Research design ... 60

Table 7: The results of the independent samples t-test in reasoning fallacies test. ... 68

Table 8: The results of independent samples t-test analysis of the English and Turkish pre-test scores ... 69

Table 9: Wilcoxon signed ranks test results of the control group ... 70

Table 10: Wilcoxon signed ranks test results of the experimental group... 70

Table 11: Mann-Whitney U-test results of the comparison between experimental and control group post-test scores ... 71

Table 12: Mann-Whitney U-test results of the gender comparison... 71

xii

Figure 1: Varieties of meaning ... 13

Figure 2: An ambiguous sentence... 17

Figure 3: An ambiguous phrase ... 18

Figure 4: Cognitive skills ... 21

Figure 5: Critical thinking dispositions ... 25

Figure 6: Criteria for a sound argument... 35

Figure 7: Mill’s classification of fallacies ... 37

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background to the Study

The world of today is more sophisticated and technological than ever. We are surrounded by media in all aspects of our lives and we are bombarded with ideas, values and advertisements. Crossley and Wilson (1979) point out language is a powerful tool, but it can be misused. People will try to persuade you by means of all sorts of appeals – by playing on your sympathies, your likes and dislikes, your fears, and so on. The key point about all of them is that they are very frequently successful as persuasive measures. But they do not succeed by logically connecting facts and drawing reasoned conclusions from them; their effect depends on trickery, emotional appeals, or threats of one sort or another. Such tricks and illogical moves are called fallacies. These fallacies can be observed in advertisements, political texts, arguments, and even in scientific articles.

Damer (2001) defines fallacy as a violation of one of the criteria of a good argument. Any argument that fails to satisfy one or more of the four criteria is a fallacious one. Fallacies, then, stem from the irrelevance of a premise, from the unacceptability of a premise, from the insufficiency of the combined premises of an argument to establish its conclusion, or from the failure of an argument to give an effective rebuttal to the most serious challenges to its conclusion or to the argument itself. Beginning with Aristotle, informal fallacies have generally been placed in one of several categories, depending on the source of the fallacy. There are fallacies of relevance, fallacies involving causal reasoning, and fallacies resulting from ambiguities.

There are few studies on fallacies in education carried out in the USA. Sukchotrat (1980) investigated the ability of Thai university freshmen to detect common fallacies in reasoning. She found that the students do not have sufficient knowledge and

experience in detecting fallacious language. In his study Laureano (1981) examined the growth in the critical reading ability of Puerto Rican students in grades four, eight and twelve. According to his study Puerto Rican public schools do not develop the skills necessary to detect fallacious language at a very high level.

Callen (1984) examined similarities and differences between elementary and secondary education majors in their ability to detect fallacies at The Florida State University and found a significant difference in favor of secondary education majors. According to the findings, she suggests that the specific fallacies in reasoning should be taught as part of coursework in the teacher education programs for both the elementary and secondary education majors.

Many other researchers such as Mosley (1978), Galotti et al. (1999), Turner (2000), Chan and Elliot (2002), and Ricco (2007) investigated fallacies in different aspects on various subjects. All these researchers found out that fallacies are neglected in education and students should be trained not only in reading comprehension skills but also in writing and speaking skills.

In addition to these studies on reasoning fallacies Callen (1984) refers to some other researches such as Lyons who concludes that many teachers could not teach because they lack the requisite skills to instruct competently. She also refers to Reutzel and Swindle’s study which reported that those who choose teaching as a career often have inadequate reading skills.

Critical reading has also been of interest in Turkey in the last two decades. Many studies on students’ critical reading skills were done by such investigators as Akyüz (1997), Çam (2006), Köse (2006), and Ünal (2006). However, no research has been done about fallacies in reasoning in Turkey.

1.2 The Purpose of the Study

In foreign language teaching, four basic skills are stressed: listening, speaking, reading and writing. However, reading is recognized as the most needed skill in the national examination in Turkey. Grammar and vocabulary are also emphasized, though the critical interpretation of the passage is often ignored. The study of texts is usually at a literal level. Rarely do the teachers spend time on teaching how to read critically.

Reading has a social dimension; individuals have social dimensions, too. Mill (1886) expresses that “The only complete safeguard against reasoning ill is the habit of reasoning well; familiarity with the principles of correct reasoning, and practice in applying those principles” (p. 482). Thus, training in critical reading and fallacies in reasoning make students and teachers better thinkers, listeners, speakers and readers.

As will be discussed in 2.4.1 below, there are several types of fallacy. However, for practical reasons we used 8 of them because the reasoning fallacies test chosen for this study included the following 8 types of fallacy: Appeal to False Authority, Either-or, Hasty Generalization, Self-contradiction, Appeal to Common Practice, Stereotyping, Part-whole, and Sexism.

The purpose of this study is to find an answer to the question of “Can critical reading skills be improved better by raising consciousness about common reasoning fallacies?” The following hypotheses were formulated for this purpose:

1. The first year teacher trainees are not able to detect reasoning fallacies. 2. The language of the test does not have any effect on the students’ results.

3. This ability cannot be improved without training; training improves the ability to detect reasoning fallacies.

4. There are significant differences between male and female students in their ability to detect certain reasoning fallacies. Considering the related literature we hypothesize that

a. there is a difference between the male and female students’ post-test scores on the appeal to false authority fallacy subtest.

b. there is a difference between the male and female students’ post-test scores on the either-or fallacy subtest.

c. there is a difference between the male and female students’ post-test scores on the hasty generalisation fallacy subtest.

d. there is a difference between the male and female students’ post-test scores on the self-contradiction fallacy subtest.

e. there is a difference between the male and female students’ post-test scores on the appeal to common practice fallacy subtest.

f. there is a difference between the male and female students’ post-test scores on the part-whole fallacy subtest.

g. there is a difference between the male and female students’ post-test scores on the stereotyping fallacy subtest.

h. there is a difference between the male and female students’ post-test scores on the sexism fallacy subtest.

1.3 Research Questions

Specifically, the research was conducted in order to find answers to the following questions:

1. Are the first year teacher trainees able to detect fallacies in reasoning?

2. If they are not able to detect them, what are the reasons? Is it because they do not have the knowledge or is it because of the language?

3. Can this ability be improved without training or should it be fostered through activities in reading courses?

4. Are there significant differences between male and female students in their ability to detect certain reasoning fallacies?

1.4 Limitations of the Study

Since there are a great number of fallacies, this study covered eight of the most common fallacies in daily life for practical reasons. As noted before, the aim of this study is not to teach the names of all these fallacies but to make students develop the habit of questioning and seeking answers while reading argumentative texts.

Although fallacies are related to all the four skills, this study is limited to the reading skill. The reason why reading was chosen is the assumption that students are better in reading than writing. Since people model their writing on the texts they read, critical reading ability should be improved first to make our students better writers. Since our courses cover both reading and writing, the students were also asked to write two argumentative texts; however, this study is limited to reading only. Improving writing skills could be the concern of another study.

This study is also limited to first year students at Gazi University because with the new curriculum the reading skill is taught only in the first year course; “Advanced Reading and Writing Skills”.

1.5 Definitions of Some Key Concepts

Critical Thinking: Critical Thinking is purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based. Critical Thinking is essential as a tool of inquiry. As such, Critical Thinking is a liberating force in education and a powerful resource in one's personal and civic life. While not synonymous with good thinking, Critical Thinking is a pervasive and self-rectifying human phenomenon. The ideal critical thinker is habitually inquisitive, well-informed, trustful of reason, open-minded, flexible, fair-minded in evaluation, honest in facing personal biases, prudent in making judgments, willing to reconsider, clear about issues, orderly in complex matters, diligent in seeking relevant information, reasonable in the selection of criteria, focused in inquiry, and persistent in seeking results which are as precise as the subject and the circumstances of inquiry permit. Thus, educating good critical thinkers means working toward this ideal. It combines developing Critical Thinking skills with nurturing those dispositions which consistently yield useful insights and which are the basis of a rational and democratic society. (Facione, 1990, p. 2)

Critical Reasoning: is a process that facilitates our examining and evaluating written and other types of communications so as to make knowledgeable judgments about the arguments set forth therein (Boyd, 2003, p. 5)

Argument: A collection of propositions in which some propositions, the

premises, are given as reasons for accepting the truth of another proposition, the conclusion. In other words, the conclusion of an argument is the proposition that is

affirmed on the basis of the other propositions in the argument. These other propositions, which are affirmed (or assumed) as providing support or reasons for accepting the conclusion as true, are the premises of that argument (Copi & Cohen, 2004, p. 3).

Fallacy: A fallacy is a defect in an argument that consists in something other than merely false premises. Fallacies can be committed in many ways, but usually they involve either a mistake in reasoning or the creation of some illusion that makes a bad argument appear good (or both) (Hurley, 2000, p. 118).

Critical Reading: Critical reading is the opposite of naivety in reading. It is a form of skepticism that does not take a text at face value, but involves an examination of claims put forward in the text as well as implicit bias in the texts framing and selection of the information presented. The ability to read critically is an ability assumed to be present in scholars and to be learned in academic institutions (wikipedia).

CHAPTER 2

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

“Language is not only the vehicle of thought, it is a great and efficient instrument in thinking.”

Humphrey Davy

2.0 Introduction

This chapter aims to give information about the foremost views about language theories and how the language is used to persuade others. The Nature and Dynamics of Language (2.1) section gives information about the how the language is formed and how it is used by referring to meaning theories. The Critical Thinking (2.2) section provides a brief overview about the critical thinking. The next section Reasoning and Arguments (2.3) introduces the concept of reasoning and assessing the reasoning in terms of arguments in a text. The section Reasoning Fallacies (2.4) explains the taxonomy of fallacies and it also explains different types of fallacies by providing examples. The last section Critical Reading in Argumentative Texts (2.5) tries to explain the relation between the reasoning fallacies and critical reading.

2.1 Nature and Dynamics of Language

Language is a very complex phenomenon and it is defined by many linguists in many different ways as in the following:

“Language is a purely human and non-instinctive method of communicating ideas, emotions and desires by means of voluntarily produced symbols” (Sapir, 1949, p.

8). He also states that “language is primarily a system of phonetic symbols for the expression of communicable thought and feeling” (Sapir, 1949, p. 17, 1951, p. 7).

“A language is a system of arbitrary vocal symbols by means of which a social group co-operates” (Bloch & Trager, as cited in Lyons, 1981, p. 4).

“A language is a set (finite or infinite) of sentences, each finite in length and constructed out of a finite set of elements” (Chomsky, 1985, p. 13).

Chomsky (1986), in his work ‘Knowledge of Language’, mentions that “Structural and descriptive linguistics, behavioral psychology, and other contemporary approaches tended to view a language as a collection of actions, or utterances, or linguistic forms (words, sentences) paired with meanings, or as system of linguistic forms or events” (p. 19).

In line with the definitions above, Hughes (2000) summarizes the definitions of language as follows:

The purpose of language, in a broader sense, is to communicate and express oneself. The number of different words in any language is finite, but these words can be used to generate an infinite number of different sentences with different meanings. Many of the ordinary things we say every day have never been said before by anyone” (p. 33).

One of the most influential philosophers of the twentieth century, Ludwig Wittgenstein (as cited in Copi & Cohen, 2005), claims that there are countless different kinds of use of what we call ‘symbols’, ‘words’, ‘sentences.’ Giving orders, describing an object or giving its measurements, reporting an event, speculating about an event, forming and testing hypothesis, presenting the results of an experiment, making up a story, play-acting, singing, guessing riddles, telling a joke, solving a problem in arithmetic, translating from one language to another, asking, cursing, greeting, and praying are some of the examples suggested by Wittgenstein (as cited in Copi & Cohen, 2005). Considering these views, form-function relation and the construction of meaning is going to be handled in terms of cognition and emotion in this section.

2.1.1 Forms and Functions of Language

Without doubt we can say that when we talk about the forms of language we refer to the types of sentences. Sentences –the units of language that express complete thoughts- are commonly placed in one of four categories: declarative, interrogative, imperative, and exclamatory (Copi & Cohen, 2005, p. 73). In general, linguists agree that although form may indicate the function, there is no one to one correspondence between form and function.

Rudinow and Barry (2004, p. 42) list three functions of language as (1)

informative function which is used to describe the world (whether rightly or wrongly)

and it claims itself as being true. For example: Ankara is the capital of Turkey. (2) expressive function which is used to evoke or express feelings. Poems can be good examples for this function. E.g. What a pity! (3) directive function which is used to influence the behavior of others; this function is commonly found in commands and requests and we cannot consider them as right or wrong. E.g. Pass the salt, please.

The famous Russian linguist Roman Jakobson (1990) states that any speech event or any act of verbal communication is composed of six elements, or factors: (1) an addresser (a sender; speaker or author), (2) a message (the verbal act, the signifier) (3) an addressee (a receiver; the hearer or reader), (4) a context , (5) a code (fully or at least partially common to the addresser and addressee ), and (6) a contact (a physical or psychological connection between the addresser and the addressee). Plus, according to him, each element is related to a different function of language and these functions are:

Referential Function: Referential, also called ‘denotative,’ ‘cognitive’ function is an orientation toward the context. It defines the relations between the message and the object to which it refers. E.g. Water boils at 100 degrees.

Emotive Function: Emotive or ‘expressive’ function is oriented toward the addresser. It tends to produce an impression of a certain emotion, as in exclamations such as Oh! and Oh my gosh!

Conative Function: Conative function is oriented toward the addressee, such as a command. E.g. Drink!

Phatic Function: Phatic function is oriented toward contact and it serves to establish, continue or discontinue communication or check whether the contact is there. E.g. Hello. What’s up?

Metalingual Function: Metalingual function is used by the participants to check up whether they use the same code. For example: I don’t follow you –what do you mean?

Poetic Function: Poetic function puts focus on the message for its own sake. On the other hand, in their book ‘Critical Thinking’, Hughes and Lavery (2004) give nine functions as (1) descriptive (to describe –to convey factual information about-something), (2) evaluative (to make a value judgment about about-something), (3) emotive (to express emotions), (4) evocative (to evoke certain emotions in an audience), (5) persuasive (to persuade people to accept something or to act in a certain way), (6) interrogative (to elicit information), (7) directive (to tell others to do something), (8) performative (to act with words), (9) recreational (to amuse ourselves or others like telling jokes and stories).

To be a successful communicator we should know the functions of language and it is important to know that language doesn’t serve just one function but generally serves more than one function. We utter something to make others do something. For example, if someone says “It is cold here.” s/he may give factual information and also may want the hearer to close the window. The functions of language may change according to the addresser’s intentions. As we shall see later, when we deal with the arguments we should keep our mind on the intention of the addresser.

2.1.2 The Construction of Meaning

The study of meaning is an enduring concern of scholarship throughout the history. Firth (1958, p. 191) states that the use of the word ‘meaning’ changes according to the context and becomes a new word when it is uttered in a new context. But how do meanings relate to speakers and to the world? We say that English word son means a ‘male descendant,’ but what is the connection between this word and ‘male descendant? The devastating fact is that different languages use different words to express the same

meanings. Thus, it might be hypothesized that the word son means what it does because speakers are conditioned to utter it when they talk about their male descendants, or because it is associated in their minds with an idea of male descendant, or because they have internalized conventions for using it in various sentential contexts to make statements, promises, predictions, etc. about male descendants. Whether or not we can accept these particular answers, they are nevertheless answers to an intelligible and important question, a question that is only partially answered by a linguistic theory of meaning, and which constrains the construction of one (Fodor, 1980, p. 12). Akmajian, Demers, Farmer and Harnish (1997) explain different types of semantic theories as:

1. The denotational theory of meaning (also called reference theory of meaning) which was first explained by Aristotle in the fourth century BC. According to this view, the meaning of each expression is the actual object it refers to, its denotation, in other words we use words to refer to the objects. The word tree refers to all the trees in the world. However, this theory has serious problems with the identification of meaning as denotation. For instance, what are the actual objects denoted by expressions such as mind, where, was/were, unfortunately, much, hello, love and after and so on. Hughes (2000) gives a reasonable example for the limitation of this theory. He gives ‘the oldest man in

the world’ as example and states that we can understand the meaning even if we

don't know its reference, and he concludes “If the meaning is the reference, then we shouldn't be able to understand what the phrase means unless we know who the oldest man in the world is” (p. 37).

2. Mentalist theories of meaning (the idea theory of meaning) were developed by John Locke in the seventeenth century. This theory considers the meaning of each word as the idea (or ideas) or mental images associated with that word in the minds of speakers. This theory also fails to explain meaning and according to Akmajian et al. (1997):

The most serious problem can be put in the problem of dilemma: Either the notion of an idea is too vague to allow the theory to predict anything specific and thus the theory is not testable; or if the notion of an idea is made precise enough to test, the theory turns out to make false predictions (p. 219).

Similarly, Hughes (2000, p. 37) explains another difficulty with this theory by asking how a person could know what he meant by the word dog and how he could know what the others meant if the mental image was the meaning, and he concludes that “We can never know what another person means by certain words”. Mentalist theories of meaning try to overcome the problems with three theories of meaning: (a) meaning as images: this theory suggests that ideas are mental images and we construct the meaning by using those images. This might be true for some words like Pegasus (flying horse) and conceivably the Eiffel Tower; however, it is not clear how it could be applied to nouns such as triangle, or verbs such as kick. For instance, the triangle could be isosceles or equilateral but would not comprise all triangles. Parallel problems come up with

kick; the gender of the kicker, which leg was used or the kind of the object being

kicked. Supposing that appropriate images could be found for all the nouns and verbs but what about the words like only, therefore, hi and not? (b) Meaning as

concepts: this theory accepts ideas as concepts, namely, as mentally represented

categories of things. This version of the idea theory is also problematic. Akmajian et al. (1997) elucidate the problems of this theory as in the following:

There is psychological evidence that our system of cognitive classification is structured in terms of prototypes, in that some instances of a concept are more typical than others; robins are more typical birds than penguins, chairs are more typical furniture than ashtrays, and so on. Yet these are not features of the meaning of bird and furniture. Even if concepts work as meanings for some words, such as common nouns, adjectives, and maybe verbs, there are still many other kinds of words that do not have clear conceptual content, such as only, not, and

hello. Furthermore, it is not clear what concept would be

assigned to a sentence. In short, theories of meaning as entities, whether they be objects denoted, images in the mind, or concepts, all face various difficulties (pp. 220-221).

(c) Meaning as sense: The meaning of a sentence is its satisfaction condition, and the meaning of a word or phrase is the contribution it makes to the satisfaction condition (truth condition, compliance condition, answerhood condition) of sentences it occurs in (Akmajian et al., 1997). According to them, this theory has many advantages when compared to denotational and mentalist theories, because it does not associate meaning with either denotations or ideas/concepts. It also

mentions the difference between the semantics of word hand, and the semantics of sentences

3. The Use Theory of Meaning:

twentieth century by Ludwig Wittgenstein and John Austin. According to t (as cited in Hughes, 2000, p.

not have any meaning. In other words, the community establishes the meaning of an expression by how they use it in their community.

In addition to these theories, we can talk about the varieties of following figure:

Figure 1: Varieties of meaning

In conclusion, all of the theories mentioned above try to explain how the meaning is constructed. They may have some weak points, but if we deal with the meaning of meaning we

of words in any language. Dictionaries cannot explain all the meanings and uses words as they can give the linguistic meanings

Language meaning

Dialect meaning Regional

mentions the difference between the semantics of words and phrases , and the semantics of sentences on the other.

The Use Theory of Meaning: This approach to meaning was developed in twentieth century by Ludwig Wittgenstein and John Austin. According to t (as cited in Hughes, 2000, p. 38) unless they are used in a context, the words do not have any meaning. In other words, the community establishes the meaning of an expression by how they use it in their community.

In addition to these theories, we can talk about the varieties of

Varieties of meaning (Akmajian et al.

In conclusion, all of the theories mentioned above try to explain how the meaning is constructed. They may have some weak points, but if we deal with the meaning of meaning we need to know them. There may be a great many words and uses

uage. Dictionaries cannot explain all the meanings and uses give the linguistic meanings only.

Meaning Linguistic meaning Language meaning Dialect meaning Social Idiolect meaning Speaker meaning literal nonliteral Irony Sarcasm

s and phrases on the one

This approach to meaning was developed in the twentieth century by Ludwig Wittgenstein and John Austin. According to them ) unless they are used in a context, the words do not have any meaning. In other words, the community establishes the meaning

In addition to these theories, we can talk about the varieties of meaning as in the

Akmajian et al., 1997) In conclusion, all of the theories mentioned above try to explain how the meaning is constructed. They may have some weak points, but if we deal with the know them. There may be a great many words and uses uage. Dictionaries cannot explain all the meanings and uses of

nonliteral

2.1.2.1 Cognitive and Emotive Meaning

A sentence or a word may both give information and express feelings. Carter (2004) differentiates these types of meanings by saying “Words or sentences that convey facts are said to have cognitive meaning; words or sentences that express or evoke emotions are said to have emotive meaning” (p. 61). Copi and Cohen (2005, p. 82) assert that the literal meanings and the emotional meanings of a word or sentence are mostly independent of one another. For instance, think about the word librarian. If we take its cognitive meanings we can find only one literal meaning as (more or less) ‘a person who works in a library’. Yet, this word may have an emotive meaning to a person via personal association. S/he may fall in love with a librarian, and when s/he hears the word librarian, s/he can remember that person. In contrast, as a student, a person may have an unpleasant quarrel with a librarian and when s/he hears, s/he might remember that time and get upset or even angry.

As Copi and Cohen (2005) note “There is nothing wrong with emotive language; neither is there anything wrong with language that is noneemotive or neutral” (p. 83). Fearnside and Holther (1959), on the other hand, warn that if the power of words is abused to evoke a specific answer, a fallacy occurs. Similarly, Diestler (1998) states a general rule for emotional use and reactions to the issues by suggesting that if one puts excessive emotional reactions to an issue, the main issue is likely to be lost. As mentioned in many books on critical thinking and reasoning (Patterson, 1993; Hughes, 2000; Gula, 2002; Swoyer, 2002; Thomson, 1996, 2002; Bowell & Kemp, 2002, 2005; Eemeren & Grootendorst, 2004; Matthew, 2004), in our daily life we are bombarded with emotive language and argumentation via written or spoken discourses in order to be persuaded especially by advertising industries and politicians. We can protect ourselves against these language tricks by being aware of the stylistic and emotive uses of language. Goatly (2000, p. 105) exemplifies the stylistic variations in vocabulary to activate the emotions in various ways (e.g. positive emotion, negative emotion and formal style etc.) in Table 1.

Table 1: Stylistic variations in vocabulary

Core Positive Negative Formal Informal Dialectical

emotion emotion (technical)

house home hovel residence pad pad

dog cur canine pooch, doggy, pooch

bow-wow

[motion, shit excrement, poo

-negative] faeces

therefore thus and so

thin slim, slender skinny ameciated

determination perseverance obstinacy motivation will-power stubbornness

bear tolerate stand, put up with

help interfere aid, assist give a hand o

prostitute [comfort whore, slag slag slag

woman -negative]

We could also provide Turkish examples like ev (neutral), yuva (positive emotion), konut, mesken (formal). As can be seen in the above table, although words may have the same meanings, the linguistic choice affects our emotions. Thus, as questioning people we should be aware of this fact and always be alert to incoming messages.

2.1.2.2 Ambiguity

Ambiguous use of language is another factor that either directly or indirectly affects our understanding, reasoning and arguments. Ambiguity can be simply defined as having double meaning and it can stem from lexis and grammar. Halpern (2003) makes the process of comprehension and cause of ambiguity precise as:

The thought in the mind of the ‘sender’ is the underlying or deep structure. The thought is private and known only to the sender. The problem in producing language is deriving surface structure from the underlying representation in the sender's mind, and the problem in comprehending language is getting from the surface structure back to the speaker's (or writer's) underlying representation… A

communication is ‘successful’ when the underlying representation constructed by the receiver matches the underlying representation of the sender… When language is ambiguous, the surface structure can have more than one meaning or underlying representation (pp. 89-90).

There are two types of ambiguity: Lexical ambiguity and grammatical ambiguity, and these ambiguities will be handled briefly.

2.1.2.2.1 Lexical Ambiguity

This type of ambiguity is also called as ‘semantical ambiguity’. Newton-Smith (2005, p. 7) defines semantical ambiguity as “Ambiguity that arises because a word in the sentence has more than one meaning”. Hudson (2000) explains that lexical ambiguity stems from homonyms in a sentence. There are two types of homonyms: Homophones (e.g. to, too, and two) and homographs (e.g. tear) (p. 313). Moreover, the reference of a word in a sentence may be unclear; in this case it is called as ‘referential ambiguity’. For example: He drove the car over his brother’s bicycle, but it wasn't hurt. In this sentence the reference of ‘it’ is ambiguous.

As Hughes and Lavery (2004) note “The referential ambiguities are usually easy to spot on and, once recognized, are easily avoided. This is especially true in conversation, since we can ask for clarification” (p. 65).

2.1.2.2.2 Grammatical Ambiguity

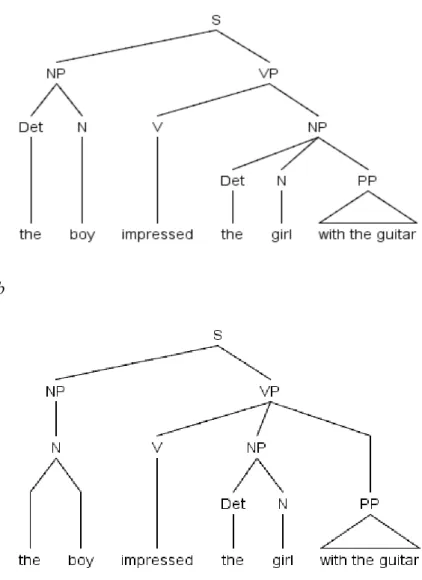

Structural ambiguity exists when a phrase or sentence has two or more meanings because of structure, either of grouping or function (Hudson, 2000, p. 314). Because this ambiguity results from the structure of a sentence, it is also called ‘structural ambiguity’. For example: The boy made an impact on the girl with the guitar.

In the example, the case is ambiguous because of the grouping and the sentence has two structures. It may be grouped as the boy made an impact on the girl with the guitar or the boy made an impact on the girl with the guitar. In the first grouping, it is inferred that the girl is carrying the guitar but in the latter it is understood that he played

the guitar and the girl was impressed. These meanings are represented in Figure 2 below:

a

b

Figure 2: An ambiguous sentence

Above, Figure 2a illustrates that ‘with the guitar’ is reduced defining relative clause, whereas Figure 2b illustrates that the boy did the action with the guitar.

To further illustrate structural ambiguity, we can examine the example three drawn by O’ Grady and Archibald (2001, p. 263) in Figure 3.

a

Figure 3: An ambiguous phrase

O’ Grady and Archibald (2001) explain the tree indicates that both the men and the

indicates that only the men are wealthy.

ambiguities as grouping ambiguities and also notes that although not so common as grouping ambigui

be boring. There are no

an important role to grasp the meaning. (namely, professors who visit) or professors

2.2 Critical Thinking

The ability to think is the basic distinctive feature of human beings. Bowell and Kemp (2005) state that much of the time in our daily life we are delimited by several messages either explicitly or implicitly tell

believe or not to believe. They suggest t

of just ignoring these messages, obeying or rejecting them without thinking. Asking for a reason means that we are asking for a j

the idea and the reason should be a good one. We can infer that critical thinking is simply to be logical whereas reflective thinking focuses

what to do. Any type of questioning

and the roots of critical thinking date back to Socrates’ method of questioning. His method was to ask probing questions that required a rational response.

b

An ambiguous phrase

O’ Grady and Archibald (2001) explain the tree as the structure on the left indicates that both the men and the women are wealthy; the structure on the right indicates that only the men are wealthy. Hudson (2000) identifies these kinds of ambiguities as grouping ambiguities and also notes that there are function

although not so common as grouping ambiguities. For example, visiting professors can be boring. There are no lexical or grouping ambiguities nevertheless functioning plays an important role to grasp the meaning. Visiting can serve either as an adjective (namely, professors who visit) or professors who get visited.

The ability to think is the basic distinctive feature of human beings. Bowell and Kemp (2005) state that much of the time in our daily life we are delimited by several messages either explicitly or implicitly telling us what to do or not to do, what to believe or not to believe. They suggest that we should ask the question ‘why?’

of just ignoring these messages, obeying or rejecting them without thinking. Asking for a reason means that we are asking for a justification for doing the action or accepting the idea and the reason should be a good one. We can infer that critical thinking is whereas reflective thinking focuses on deciding what to believe or type of questioning initiates a process that involves critical thinking he roots of critical thinking date back to Socrates’ method of questioning. His method was to ask probing questions that required a rational response.

as the structure on the left women are wealthy; the structure on the right Hudson (2000) identifies these kinds of there are function ambiguities isiting professors can nevertheless functioning plays can serve either as an adjective

The ability to think is the basic distinctive feature of human beings. Bowell and Kemp (2005) state that much of the time in our daily life we are delimited by several ing us what to do or not to do, what to hat we should ask the question ‘why?’ instead of just ignoring these messages, obeying or rejecting them without thinking. Asking for ustification for doing the action or accepting the idea and the reason should be a good one. We can infer that critical thinking is on deciding what to believe or that involves critical thinking he roots of critical thinking date back to Socrates’ method of questioning. His method was to ask probing questions that required a rational response. Although it dates

back to Socrates, Dewey is accepted as the founder of the contemporary critical thinking. Dewey (as cited in Kurfiss, 1988, p. 7) defines reflective thinking as:

Active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusions to which it tends that includes a conscious and voluntary effort to establish belief upon a firm basis of evidence and rationality.

Another early researcher who contributed to critical thinking is Ennis and his early definition of critical thinking was “correct assessments of statements” and more recently he has defined it as “Reflective and reasonable thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do” (as cited in Kurfiss, 1998, p. 8).

Many attempts have been made to define critical thinking and there are various definitions of critical thinking; however, the Delphi Project scientists tried to reach a consensus for purposes of assessment and instruction in education put forth the definition, known as the Delphi definition of the critical thinking is as follows:

We understand critical thinking to be purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based. Critical Thinking is essential as a tool of inquiry. As such, Critical Thinking is a liberating force in education and a powerful resource in one's personal and civic life. While not synonymous with good thinking, Critical Thinking is a pervasive and self-rectifying human phenomenon. The ideal critical thinker is habitually inquisitive, well-informed, trustful of reason, open-minded, flexible, fair-minded in evaluation, honest in facing personal biases, prudent in making judgments, willing to reconsider, clear about issues, orderly in complex matters, diligent in seeking relevant information, reasonable in the selection of criteria, focused in inquiry, and persistent in seeking results which are as precise as the subject and the circumstances of inquiry permit. Thus, educating good critical thinkers means working toward this ideal. It combines developing Critical Thinking skills with nurturing those dispositions which consistently yield useful insights and which are the basis of a rational and democratic society. (Facione, 1990, p. 2)

Facione (2010) proposes six questions for effective thinking and problem-solving in the form of an acronym as “IDEALS”. They are:

Identify the problem. —“What’s the real question we’re facing here?”

Define the context. —“What are the facts and circumstances that frame this problem?”

Enumerate choices. —“What are our most plausible three or four options?” Analyze options. —“What is our best course of action, all things considered?” List reasons explicitly. —“Exactly why are we making this choice rather than

another?”

Self-correct. — “Okay, let’s look at it again. What did we miss?”

Pirozzi (2003, p.197) describes critical thinking as “A very careful and thoughtful way of dealing with events, issues, problems, decisions, or situations”. As can be understood from the definition, critical thinking plays an important part in one’s life since it makes a person more careful and a better decision maker. As mentioned earlier, when a person becomes a critical thinker, s/he does not accept all the things blindly but filters them by questioning.

Consequently, as Browne and Keeley (2007, p. 2) accentuate, critical thinking refers to the talent to ask and answer hard hitting questions at the right time and the enthusiasm to use these questions actively. In Delphi Report, experts suggested a list of mental abilities and attitudes or habits including cognitive skills and dispositions. Next sections will cover these skills and dispositions.

2.2.1 Cognitive Operations

The experts, who attended the Delphi Project, included crucial cognitive skills as interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation. To further illustrate the cognitive skills, consider Figure 4 below (Facione, 2010).

Figure 4: Cognitive Skills

These skills and their sub-skills were defined by the experts; these skills are: Interpretation is to comprehend and express the meaning or significance of a wide variety of experiences, situations, data, events, judgments, conventions, beliefs, rules, procedures or criteria. Analysis is to identify the intended and actual inferential relationships among statements, questions, concepts, descriptions or other forms of representation intended to express beliefs, judgments, experiences, reasons, information, or opinions. Evaluation is to assess the credibility of statements or other representations which are accounts or descriptions of a person's perception, experience, situation, judgment, belief, or opinion; and to assess the logical strength of the actual or intend inferential relationships among statements, descriptions, questions or other forms of representation. Inference is to identify and secure elements needed to draw reasonable conclusions; to form conjectures and hypotheses; to consider relevant information and to educe the consequences flowing from data, statements, principles, evidence, judgments, beliefs, opinions, concepts, descriptions, questions, or other forms of representation. Explanation is to state the results of one's reasoning; to justify that reasoning in terms of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological and contextual considerations upon which one's results were based; and to present one's reasoning in the form of cogent arguments. Self-regulation is “self-consciously to monitor one’s cognitive activities, the elements used in those activities, and the results educed, particularly by applying skills in analysis, and evaluation to one’s own inferential judgments

Purposeful Reflective Judgment Analysis Interpretation Self-regulation Inference Explanation Evaluation

with a view toward questioning, confirming, validating, or correcting either one’s reasoning or one’s results. (Facione, 1990, pp. 6-10)

They also defined the sub-skills of these cognitive skills, but they are not going to be given in detail here. Although there are other sub-skills given by experts, they included some relatively important ones. To see these sub-skills, please see the table 2 below:

Table 2: Consensus list of cognitive skills and sub-skills

Skill Sub-Skills

1. Interpretation Categorization

Decoding Significance Clarifying Meaning

2. Analysis Examining Ideas

Identifying Arguments Analyzing Arguments

3. Evaluation Assessing Claims

Assessing Arguments

4. Inference Querying Evidence

Conjecturing Alternatives Drawing Conclusions

5. Explanation Stating Results

Justifying Procedures Presenting Arguments

6. Self-Regulation Self-examination

Self-correction

(Facione, 1990)

When discussing critical thinking, it would be unwise not to mention Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Bloom’s taxonomy continues to be widely accepted and taught. He was the Director of the Board of Examination at the University of Chicago thought of a framework to facilitate exchange of test items among faculty

across several colleges. From 1949 to 1956, measurement specialists, including Bloom, met every six months. Their objective was to create banks of tests items to measure educational objectives across the colleges (Anderson & Krathwhol as cited in Özmen, 2006)

Benjamin Bloom and his colleagues developed a list of educational objectives under three categories as cognitive (knowledge), psychomotor (skills), and affective (attitude) and they published them in 1956. In his book, Taxonomy of Educational Objectives –Handbook I, Bloom (1956) and his colleagues explained the levels of cognitive domain as knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation. Then Kratwohl, Bloom and Masia explained the affective domain in another book, whose name is Taxonomy of Educational Objectives –Handbook II, published in 1964. Kratwohl, Bloom and Masia (1964) named the levels of affective domain as receiving, responding, valuing, organization, and characterization by a value or value complex.

2.2.2 Dispositions

Several pedagogical and assessment implications follow from the dispositional dimension of Critical Thinking, implications which might not be apparent if educators focused only on the skill dimension of Critical Thinking. The education of good critical thinkers is more difficult than training students to execute a set of cognitive skills. For example, in terms of pedagogy, modelling how to evaluate critically the information which students would normally accept uncritically and encouraging them to do the same can do wonders for developing their confidence in their Critical Thinking ability (Facione, 1990, p. 14).

The expert consensus in Delphi Project (83%) recommended that good critical thinkers can be characterized as exhibiting the following dispositions which are explained under two categories as:

Approaches to life and living in general:

concern to become and remain generally well-informed, alertness to opportunities to use Critical Thinking, trust in the processes of reasoned inquiry,

self-confidence in one's own ability to reason, open-mindedness regarding divergent world views, flexibility in considering alternatives and opinions, understanding of the opinions of other people, fair-mindedness in appraising reasoning, honesty in facing one's own biases, prejudices, stereotypes, egocentric or sociocentric tendencies, prudence in suspending, making or altering judgments, willingness to reconsider and revise views where honest reflection suggests that change is warranted.

Approaches to specific issues, questions or problems: clarity in stating the question or concern,

orderliness in working with complexity, diligence in seeking relevant information,

reasonableness in selecting and applying criteria, care in focusing attention on the concern at hand, persistence though difficulties are encountered,

precision to the degree permitted by the subject and the circumstance.

(Facione, 1990, p. 13) To summarize Critical Thinking dispositions Facione (2010) provides a clear illustration as follows:

Figure 5: Critical thinking dispositions

After this brief introduction of Critical Thinking briefly, we are now going to deal with Critical Reasoning and Arguments in the subsequent parts.

2.3 Reasoning and Arguments

Reasoning is the indispensible part of critical thinking and in our life, we need reasoning to solve problems. For the last few decades, there have been some controversies regarding the differences between argumentation and reasoning. Walton (1990) distinguishes them by defining reasoning as “A sequence of steps from some points (premises) to other points (conclusions)” (p. 404). He, then, explains that the premises generally stand for propositions, but they can also represent the components of other speech acts, such as interrogative and imperative utterances, in some circumstances. On the other hand, he defines argument as “A social and verbal means of trying to resolve or at least to contend with, a conflict or difference that has arisen or existed between two (or more) parties” (p. 441). According to him in an argument there must be a claim put forward by one of the parties and the opposing party must question that claim. Arguments may result from a disagreement, an unsolved problem, an unverified hypothesis. Human beings use various ways to overcome these problematic situations by using different types of arguments.

Cottrell (2005, p. 3) states that reasoning starts with ourselves and it includes: having reasons for what we believe and do, and being aware of what these are;

Inquisitive Judicious Truthseeking Confident in Reasoning open-minded Analytical Systematic

critically evaluating our own beliefs and actions;

being able to present to others the reasons for our beliefs and actions.

Similarly, Diestler (1998, p. 82) emphasizes that knowing common patterns of reasoning will help us to be aware of the process in reasoning, to assess the arguments we encounter, and to discover and inspect hypotheses underlying premises and conclusions.

Traditionally logic proposed two basic means of reaching conclusion: induction (or inductive reasoning) and deduction (or deductive reasoning). Induction (from Latin

in=into + ducere = to lead) means building from specifics to general conclusion.

Deduction (from Latin de = away from + ducere = to lead) is just the opposite process (Goshgarian & Krueger, 1994, p. 77).

2.3.1 Deductive Reasoning

In their definition of deductive reasoning, Rasool, Banks and McCarthy (1993), Kahane and Cavender (2006), and Walton (2006) explain that the conclusion of an argument must be true when all the propositions are true, because although implicitly stated in the propositions, the conclusion has already been stated by them, so it must follow logically.

In traditional deductive logic, an argument is evaluated in a one-step process. A deductive model, such as propositional calculus, is directly applied to the argument, and tests out whether the argument is valid or not (Walton, 2008a, p. 145). Here are two examples for deductive reasoning:

Argument 1

Premise 1:All leaders experience stress in their lives. Premise 2: Atatürk was a leader.

Conclusion: Therefore, he must have experienced stress in his life.

Argument 2

Premise 1: If this wire is made of copper, then it will conduct electricity. Premise 2: This wire is made of copper.

Conclusion: This wire will conduct electricity. (Kahane & Cavender,

2006, p. 9)

In both examples, the premises are commonly accepted as true, thus the conclusion must be true according to deductive reasoning. However, as we shall discuss in 2.3.5.2 deductive reasoning can be challenged in some ways and fail to confirm the conclusion.

2.3.2 Inductive Reasoning

Unlike deductive reasoning, inductive reasoning is not strict and linear. Hughes (2000) affirms this difference by saying “Inductive arguments are distinguished from deductive arguments by the fact that they lack the ability to guarantee their conclusions” (p. 211). The definition of this type of argument is that “If the premises are true, the conclusion is probably true, but it could possibly be false” (Rasool et al., 1993; Hurley, 2000;Starkey, 2004; Walton, 2005, 2006).

As mentioned in the definition, when one reasons inductively, he begins with a piece of evidence and adds it to another, then another, until he has gathered enough support to arrive at a general conclusion. The following example can elucidate the process of inductive argument.

Premise 1. Tiredness can cause illness.

Premise 2. John has been working too much nowadays. Premise 3. John is ill.

Conclusion: Therefore, tiredness may be the cause of his illness.

As mentioned before, both deductive and inductive reasoning are classical way of reasoning and are still used for general purposes; nonetheless, when it comes to critical reasoning they may be challenged, and we will cover this in evaluating arguments part.

2.3.3 Critical Reasoning

To begin with, Scull (1987) mentions that Greeks introduced the word ‘logic’ and it is still used to depict the reasoning process in the evaluation of any proposition. Plato (c.428-348 B.C.) and Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) trained their students to think evidently and critically about the premises given in arguments and to use valid induction and deduction to accept conclusions (p. 245).

Cederbloom and Paulsen (2005) explain critical reasoning by distinguishing it from mere disagreement:

When we engage in mere disagreement, we seek to maintain the same beliefs we held prior to considering a new position. When we engage in critical reasoning, we cultivate an attitude of relative detachment. If an arguer points out that reasons we ourselves would accept really support a specific conclusion and therefore would compel us to give up some conflicting view we hold, we see this as a gain, not a loss. (p. 5)

Critical reasoning is a skill, and like all the skills it can be improved by practice. Critical reasoning can be practiced almost all the time in our lives; while reading, listening and talking to other people, and observing the world around you. Boyd (2003, p. 5) defines critical reasoning as a process that facilitates our examining and evaluating written and other types of communications so as to make knowledgeable judgments about the arguments set forth therein. Therefore, it can be said that the study of critical reasoning improves all four skills; listening, reading, speaking and writing.

As noted before, critical reasoning and thinking requires asking questions to the arguments that are presented to us. Asking questions can help us figure out the others’ reasoning and it can also help us determine the strong and weak points of the arguments. Browne and Keeley (2007, p. 83) suggest the following questions to apply in our reasoning:

1. What are the issue and the conclusion? 2. What are the reasons?

3. What words or phrases are ambiguous?