www.elsevier.es/ram

R

E

V

I

S

T

A

A

R

G

E

N

T

I

N

A

D

E

MICROBIOLOGÍA

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Biofilm-forming

capacity

of

blood---borne

Candida

albicans

strains

and

effects

of

antifungal

agents

Hanni

Turan

∗,

Müge

Demirbilek

DepartmentofMicrobiology,FacultyofMedicine,Bas¸kentUniversity,Ankara,Turkey

Received6November2016;accepted5May2017 Availableonline6October2017

KEYWORDS Candidaalbicans; MBIC; Christensenmethod; Calgarymethod; Inhibitionofbiofilm formation

Abstract InfectionsrelatedtoCandidaalbicansbiofilmsandsubsequentantifungalresistance havebecomemorecommonwiththeincreaseduseofindwellingmedicaldevices.Regimens forpreventingfungalbiofilmformationareneeded,particularlyinhigh-riskpatients.Inthis study,weinvestigatedthebiofilmformationrateofmultiplestrainsofCandidaalbicans(n=162 clinicalisolates),theirantifungalsusceptibilitypatterns,andtheefficacyofcertainantifungals forpreventingbiofilmformation.BiofilmformationwasgradedusingamodifiedChristensen’s 96-wellplatemethod. Wefurtheranalyzed 30randomlychosenintensebiofilm-forming iso-latesusingtheXTTmethod.Minimumbiofilminhibitionconcentrations(MBIC)ofcaspofungin, micafungin,anidulafungin,fluconazole,voriconazole,posaconazole,itraconazole,and ampho-tericinBweredeterminedusingthemodifiedCalgarybiofilmmethod.Inaddition,theinhibitory effectsofantifungalagentsonbiofilmformationwereinvestigated.Ourstudyshowedweak, moderate,andextensivebiofilmformationin29%(n=47),38%(n=61),and23%(n=37)ofthe isolates,respectively.WefoundthatechinocandinshadthelowestMBICvaluesandthat itra-conazoleinhibitedbiofilmformationinmoreisolates(26/32;81.3%)thanothertestedagents.In conclusion,echinocandinsweremosteffectiveagainstformedbiofilms,whileitraconazolewas mosteffectiveforpreventingbiofilmformation.Standardizedmethodsareneededforbiofilm antifungalsensitivity tests when determining thetreatment and prophylaxisof C. albicans infections.

©2017Asociaci´onArgentinadeMicrobiolog´ıa.PublishedbyElsevierEspa˜na,S.L.U.Thisisan openaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). PALABRASCLAVE Candidaalbicans; MBIC; Métodode Christensen;

CapacidaddeformacióndebiopelículasdelascepasdeCandidaalbicans detransmisiónsanguíneayefectosdelosagentesantifúngicos

Resumen Las infecciones relacionadascon las biopelículasde Candida albicans y la con-siguienteresistenciaantifúngicasehanvueltofenómenoshabitualesconelusocrecientede

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:hannituran@yahoo.de(H.Turan).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ram.2017.05.003

0325-7541/©2017Asociaci´onArgentinadeMicrobiolog´ıa.PublishedbyElsevierEspa˜na,S.L.U.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCC BY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

MétododeCalgary; Inhibiciónde formaciónde biopelículas

dispositivos médicos permanentes.Son necesarios regímenes paraprevenir laformación de biopelículasfúngicas,enespecialenlospacientesdealtoriesgo.Enesteestudioseinvestigóla tasadeformacióndebiopelículasdenumerosascepasdeCandidaalbicans(162aislados clíni-cos),suspatronesdesensibilidadalosantifúngicosylaeficaciadealgunosdeestosagentes paraprevenirlaformacióndebiopelículas.Laformacióndebiopelículasseclasificóutilizando elmétododeChristensenmodificadode96pocillos.Posteriormenteseanalizaron30aisladosde formaciónintensadebiopelículaselegidosalazar,utilizandoelmétodoXTT.Secalcularonlas concentracionesmínimasdeinhibicióndebiopelículas(minimumbiofilminhibition concentra-tions,MBIC)delacaspofungina,lamicafungina,laanidulafungina,elfluconazol,elvoriconazol, elposaconazol,elitraconazolylaanfotericinaB,utilizandoelmétodomodificadode biopelícu-lasdeCalgary.Además,seinvestigaronlosefectosinhibitoriosdelosagentesantifúngicossobre laformacióndebiopelículas.Nuestroestudioencontróunaformacióndébil,moderadaeintensa debiopelículasenel29%(n=47),38%(n=61)y23%(n=37)delosaislados,respectivamente. EncontramosquelasequinocandinasmostraronlosmenoresvaloresMBIC,yqueelitraconazol inhibiólaformacióndebiopelículasenmásaislados(26/32;81,3%)queotrosagentesensayados. Enconclusión,lasequinocandinasresultaronmáseficacesfrentealasbiopelículasformadas, mientrasqueelitraconazolresultómáseficazparaprevenirlaformacióndebiopelículas.Se necesitacontarconmétodos estandarizadospara efectuar laspruebasde sensibilidadalos antifúngicosentérminosdeformacióndebiopelículasalahoradedeterminareltratamiento ylaprofilaxisdelasinfeccionesporC.albicans.

©2017Asociaci´onArgentinadeMicrobiolog´ıa.PublicadoporElsevierEspa˜na,S.L.U.Esteesun art´ıculoOpenAccessbajolalicenciaCCBY-NC-ND( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Candida species are the most frequently isolated human fungal pathogens and causea wide spectrumof diseases, including superficial mucosal, severe deep, and systemic infections42,44. The increased use of biomaterial

implan-tations, bone marrow and solid organ transplantations,

immunosuppressive treatment, and the use of

broad-spectrum antibiotics are associated with severe systemic infections44.

One of the most important virulence factors of Can-didainfectionsinvolvestheformationofbiofilms42.Candida

species have differing abilities for biofilm formation and frequentlyplayaroleinbiofilm-associatedinfections42.In

particular,Candidaalbicansisanintenselybiofilm-forming fungus12,23.

Cells in the biofilm are protected from the external environment, immune system, and antifungal treatment; in fact, the most important characteristic of biofilms is their high antimicrobial resistance42. Different

antimicro-bialshavebeenusedininfectionsduetoC.albicans14,31,43,

whose biofilmsshowhigh resistancetofluconazole,a fre-quently preferred treatment2,34,42. Amphotericin B shows

dose-dependentactivity,whileechinocandinshaveinvitro

action againstbiofilms20,24,42,43.Although most newazoles

affectplanktoniccells,theydonotsufficientlyinhibitsessile cells20,24,43.

Because planktonic and sessile forms of microorgan-ismshavedifferentantimicrobialsusceptibilities,treatment strategiesbasedonminimalinhibitoryconcentration(MIC) resultsofplanktoniccellsmayfail.

The incidenceof life-threateningbiofilm-related infec-tionshasgrownwithanincreasingnumberofoncologicaland immunosuppressedpatientsandtheuseofindwelling medi-calequipment;therefore,prophylactictreatmentstrategies areneeded15,16.Few studieshave investigatedthe benefit

ofadministeringantifungalsatsubinhibitoryconcentrations forinfectionprophylaxisandtheirinhibitoryeffectson Can-didabiofilmformation.

Inthisstudy,wedeterminedtherateofbiofilm forma-tionin C. albicans strainsthat frequently cause systemic infections.Wethencomparedtheantifungalsusceptibility profilesofplanktonicandsessileformsandtheefficacyof antifungals at subinhibitory concentrations for preventing biofilmformationinselectedisolates.

Materials

and

methods

Microorganisms

Inthisstudy,weincluded162C.albicansisolatesfromblood culturesofpatientsinAnkara,Adana,andIstanbulhospitals ofBas¸kent University. Onlyone isolate fromeach patient withinamonthwasselected.Thestrainswereclassifiedas

C.albicansoritsrelatedspeciesbasedongermtube forma-tionandcolonymorphologies onCornMealTween80agar (BD,France/USA).

We randomly chose 30 strains that formed extensive biofilms based on biofilm density (modified Christensen method), C. albicans ATCC 90028, and C. albicans ATCC 10231forsubsequentexperiments.

Growthconditions

StrainswerekeptinSkimMilk(BD,France/USA)at−80◦C. Foreachexperiment,thestrainswerepassedonSabouraud dextrose agar (SDA, BD, France, USA) twice for purity control, then selected colonies were suspended in Yeast Nitrogen Base (YNB) broth and incubated at 37◦C until theyeastcellsenteredthebuddingphase.Theyeastcells werewashedtwice withsterile phosphate buffer solution and adjusted to a standard turbidity of 1---3×107CFU/ml

inYNBbrothusingaspectrophotometer(PhoenixSpec,BD, USA/Ireland)21,30.Yeast cellsuspensionswerepreparedfor

allexperimentsasdescribedabove.

Measurementofbiofilmdensity

One hundred microliters of prepared yeast suspension were transferred into 96-well, flat-based microplates (Costar3599, USA). The plates wereincubated at 37◦C in static conditions to allow biofilms to form. Wells were washedwith250lPBS(pH7.4)threetimesafter incuba-tiontoremovenon-adherentcells4.AmodifiedChristensen

method was usedto quantify biofilm formation and den-sity.Theopticaldensity(OD540nm)valuesforeverywellwere

determinedwithanELx800(Bio-TekInstrumentsInc.,USA) microplatespectrophotometer.Eachstrain occupiedthree wells,andnegativecontrols(mediablanks)wereincluded inat least6wells.Allexperimentswererepeatedatleast twiceondifferentdays.

Fourbiofilm density categorieswereusedtogradethe biofilms based onestablished cut-off values (ODc), which

were derived from the mean values of negative controls (meanODnc)summedwiththreestandarddeviationsofthe

negative controls (3×SDnc): ODc=mean ODnc+(3×SDnc).

Thebiofilmdensitycategoriesusedareasfollows: OD ≤ ODC = biofilmnegative

ODC ≤ OD ≥ 2×ODC = mildlypositiveforbiofilm

2×ODC ≤ OD ≥ 4×ODC = moderatelypositiveforbiofilm

4×ODC ≤ OD = intenselypositiveforbiofilm

Thebiofilmdensitygradeofeachstrainwasdetermined inrelationwithitsmeanODvalue4,40.

Biofilmmeasurementsinplateswithneedlelids

The biofilm-forming abilities of 30 clinical isolates with intensebiofilm-formingcapacity,aswellasC.albicansATCC 10231andC.albicansATCC90028,wereinvestigatedusing the XTT method in 96-U-well microplates (Thermo-Nunc, TSP-screening,Denmark)withneedlelids.Allstrainswere testedin3wellsandincubatedunderflowconditionsat37◦C for48h,thentheneedlelidwaswashedtwice.

Three hundred mg/l XTT (Applichem, Germany) and

0.13mMmenadione (Sigma,Germany)weredistributedto producelast-wellconcentrations39andtheneedlelidswere

closed.Theplateswereincubatedatstaticconditionsinthe darkfor2hat37◦C.Theneedlelidwasopened,OD490nm

val-uesweremeasuredasdescribedabove,andresultingcolor changeswereobservedvisually.

Antifungalsusceptibilitytests

Invitroantifungalsusceptibilitiesofplanktoniccellsofthe 30 strains showing intense biofilm formation, C. albicans

ATCC90028,andC.albicansATCC10231weredetermined bythemicrodilutionmethodinaccordancewithCLSIM27-A3 (S4)criteria46.Standardpowderformsofantifungalagents

including caspofungin (Merck, USA), micafungin (Astellas, Japan), anidulafungin (Pfizer, USA), fluconazole (Sigma), voriconazole(Sigma),posaconazole(Merck,USA), itracona-zole(Sigma),andamphotericinB(Sigma)wereused.

The antifungalsusceptibility tests ofsessile cells were performed in accordance with a modified Calgary biofilm method9. We generated 48 h biofilms in needle lids of

96-well microplatesasmentioned above.Antifungalstock solutions weredilutedwithYNB brothsupplementedwith 100mM sucrose (Merck, Germany), two-fold serial dilu-tions were made. The antifungal concentration ranges were adjusted as follows: 0.06---32g/ml for echinocan-dins,0.25---128g/mlforamphotericinBanditraconazole, 0.5---256g/mlforposaconazole,1---512g/mlfor voricona-zole,and4---2048g/mlforfluconazole.

Needlelidswithformedbiofilmswerewashedandplaced inpreparedplateswithantifungalagentsandincubatedat 37◦Cfor24h.Afterincubation,theneedlelidwaswashed twicewithPBSandtransferredintothemicroplate contain-ing200lfreshYNBwithsucrose.Theplatewassonicated at highpower for 5min(UltrasonicCleaner, Daihan Scien-tificCo.,Korea),andincubatedatstaticconditionsat37◦C for 24h. The resultingmaterial wasanalyzed visuallyand withamicroplate spectrophotometerat 630nm. The con-centrationsofamphotericinBthatinhibitedallgrowthand ofechinocandinsandazolesthatsignificantlylimitedfungal growth(≥50%)weretheminimalbiofilminhibition concen-tration (MBIC) values. The MICs of the planktonic forms andMBICsofsessilecellsofthe32strainswerecompared, andthedecreased antifungalsusceptibilityofsessilecells (MBIC/MICratio)wascalculated.

Biofilminhibitionexperiment

Forthisexperiment,quadrupledMICvaluesdeterminedby CLSIreferencemethodswerechosenasthestarting concen-tration for eachantifungal compound,andtwo-fold serial dilutionsweremadeacrosseachrow.

Each yeast suspension was inoculated into each well so that yeastcells were incubated withMIC/2 --- MIC/128 sub-MICs of the antifungals. Needle lids were placed on themicroplates,andtheplateswereincubatedunderflow conditions on an orbital shaker for 48h at 37◦C for cell adherence. After incubation, the needle lid was washed twicewithPBS.Sonicationwasperformedathighpowerfor 5min.DilutionsandspotinoculationstoSDAwereperformed

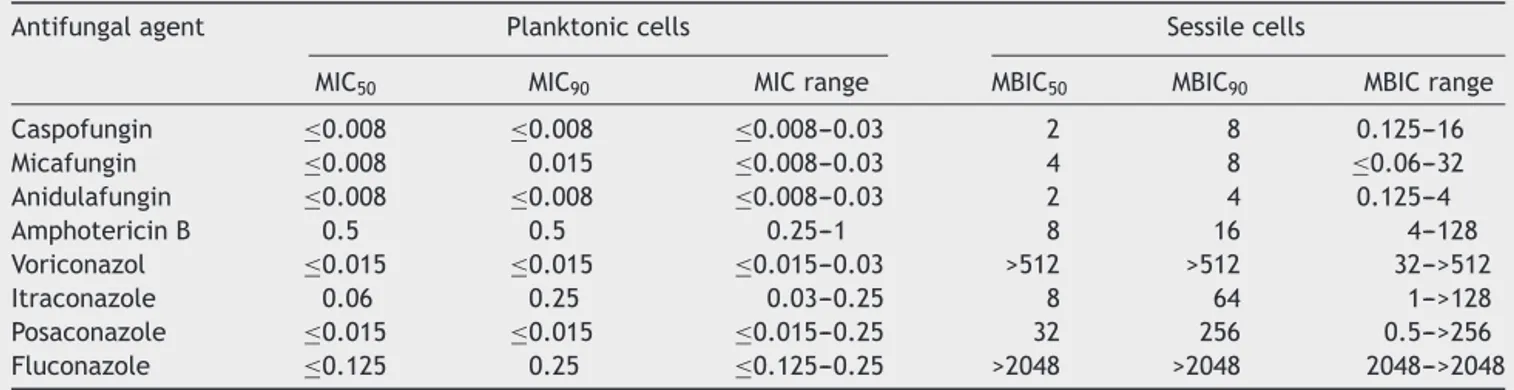

Table1 Antifungalsusceptibilitytestresultsforplanktonic(MIC)andsessile(MBIC)cells(g/ml)of32C.albicansstrains

Antifungalagent Planktoniccells Sessilecells

MIC50 MIC90 MICrange MBIC50 MBIC90 MBICrange

Caspofungin ≤0.008 ≤0.008 ≤0.008---0.03 2 8 0.125---16 Micafungin ≤0.008 0.015 ≤0.008---0.03 4 8 ≤0.06---32 Anidulafungin ≤0.008 ≤0.008 ≤0.008---0.03 2 4 0.125---4 AmphotericinB 0.5 0.5 0.25---1 8 16 4---128 Voriconazol ≤0.015 ≤0.015 ≤0.015---0.03 >512 >512 32--->512 Itraconazole 0.06 0.25 0.03---0.25 8 64 1--->128 Posaconazole ≤0.015 ≤0.015 ≤0.015---0.25 32 256 0.5--->256 Fluconazole ≤0.125 0.25 ≤0.125---0.25 >2048 >2048 2048--->2048 MIC:minimalinhibitoryconcentration,MBIC:minimalbiofilminhibitionconcentration,MIC50:MICvalue,whichinhibits50%ofthetested

strains,MBIC50:MBICvalue,whichinhibits50%ofthetestedstrains,MIC90:MICvalue,whichinhibits90%ofthetestedstrains,MBIC90:

MBICvalue,whichinhibits90%ofthetestedstrains,MICrange:rangeofMICvaluesofalltestedstrains,MBICrange:rangeofMBIC valuesofalltestedstrains.

fromthewells,andtheagarplateswereincubatedat37◦C for48h.Inaddition,theneedlelidwasremoved,andthe platewasincubatedat37◦Cfor24h.

Wellswereanalyzed visuallyandbyusingamicroplate spectrophotometerat630nm.TheCFU/mlvalueswere cal-culated for colonies grown after spot inoculations. The biofilm inhibitory concentration (BIC) for each antifungal agentthatinhibitedallgrowthforeachstrainwasrecorded. Lowerinhibitionlevelswerenotconsidered.

Statisticalanalysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 17.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago,IL,USA).TheFriedmantestwasusedfor compar-ingthe mediansof thegroups. Results werepresented as mean±standarddeviation,median,interquartilerange,or geometricmeans.Atwo-proportionZtestwasusedto com-paretheproportions,whichwerepresentedasnumber(n) and percentage (%). The relationships and effects among antifungalswereanalyzedusingtheSpearman’srho corre-lationcoefficient.Statisticalsignificancewassetatp<0.05.

Results

Biofilmformation

Many of the strains showed moderate biofilm formation (38%,n=61),47(29%)strainsshowedweak biofilm forma-tion,37(23%)strainsshowedintensebiofilmformation,and 17strains(10%)didnotformbiofilms.Intensebiofilm for-mationwasalsoobservedinC.albicansATCC10231,while weak biofilm formation was observed in C.albicans ATCC 90028.

The biofilm capacity of 30 intensely biofilm-forming strainsandthetwostandardstrainswerefurtheranalyzed usingtheXTTcolorimetricmethodinmicroplateswith nee-dlelidsbyshowingthemetabolicactivityofthesessilecells expressedasdensitylevelsbetween1+and3+.Inaddition, yeastcolonies were visuallyobserved on needles insome strains.

Planktoniccellantifungalsusceptibility

Table 1 shows the antifungal susceptibility results of the 32strains.Only 5clinical isolates(16.7%)and C.albicans

ATCC10231exhibiteddose-dependentsusceptibilityto itra-conazole.

Biofilmsusceptibilitytoantifungals

Table1alsoshowsbiofilmsusceptibilityresults. Echinocan-dins had the lowest MBIC values (MBIC50 of 2g/ml for

caspofunginandanidulafunginand4g/mlformicafungin; MBIC90 of4g/mlforanidulafunginand8g/mlfor

caspo-fungin and micafungin. The lowest MBIC90 (4g/ml) was

obtainedwith anidulafungin.Among the azoles, itracona-zolehadthelowestMBIC50andMBIC90values(8g/mland

64g/ml,respectively).

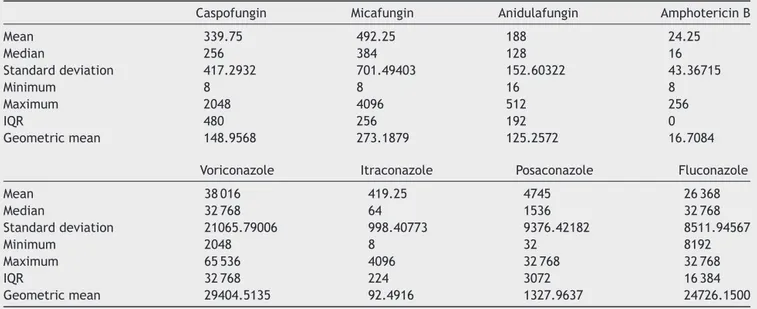

Comparisonofantifungalsusceptibilities ofplanktonicandsessilecells

Amongthe32strainstested,MBICvaluesoftheantifungals weregreaterthantheirMICvalues(Table1).Table2shows MBIC/MICratiosoftheantifungals,showingthatthemedian MBIC/MICratioofamphotericinBhadthelowestMBIC/MIC ratioamongtheantifungals(p<0.05).TheMBIC/MICratioof micafunginwassignificantlyhigherthantheotherantifungal agents.TheMBIC/MICratioofposaconazolewassignificantly lowerthanfluconazoleorvoriconazole,whoseratioswere thehighestamongtheazolestested(p<0.05).

The analysis of MBIC/MIC ratio correlations of the antifungals revealed that caspofungin significantly corre-lated with micafungin (Spearman’s rho=0.572, p<0.001) and anidulafungin (Spearman’s rho=0.414, p<0.05) and

had similar effects on the 32 strains. Posaconazole

showed significant correlations with voriconazole (Spear-man’s rho=0.402, p<0.05) and itraconazole (Spearman’s rho=0.684,p<0.001).Insummary,antifungalsinthesame groupshowedsimilareffectsontheyeaststrains;however, nosignificantcorrelationsoftheeffectsamongthedifferent

Table2 MBIC/MICratiovaluesofsessileandplanktoniccells

Caspofungin Micafungin Anidulafungin AmphotericinB

Mean 339.75 492.25 188 24.25 Median 256 384 128 16 Standarddeviation 417.2932 701.49403 152.60322 43.36715 Minimum 8 8 16 8 Maximum 2048 4096 512 256 IQR 480 256 192 0 Geometricmean 148.9568 273.1879 125.2572 16.7084

Voriconazole Itraconazole Posaconazole Fluconazole

Mean 38016 419.25 4745 26368 Median 32768 64 1536 32768 Standarddeviation 21065.79006 998.40773 9376.42182 8511.94567 Minimum 2048 8 32 8192 Maximum 65536 4096 32768 32768 IQR 32768 224 3072 16384 Geometricmean 29404.5135 92.4916 1327.9637 24726.1500

MIC:minimalinhibitoryconcentration,MBIC:minimalbiofilminhibitionconcentration,IQR:interquartilerange.

groups (echinocandins, azoles, and amphotericin B)were observed.

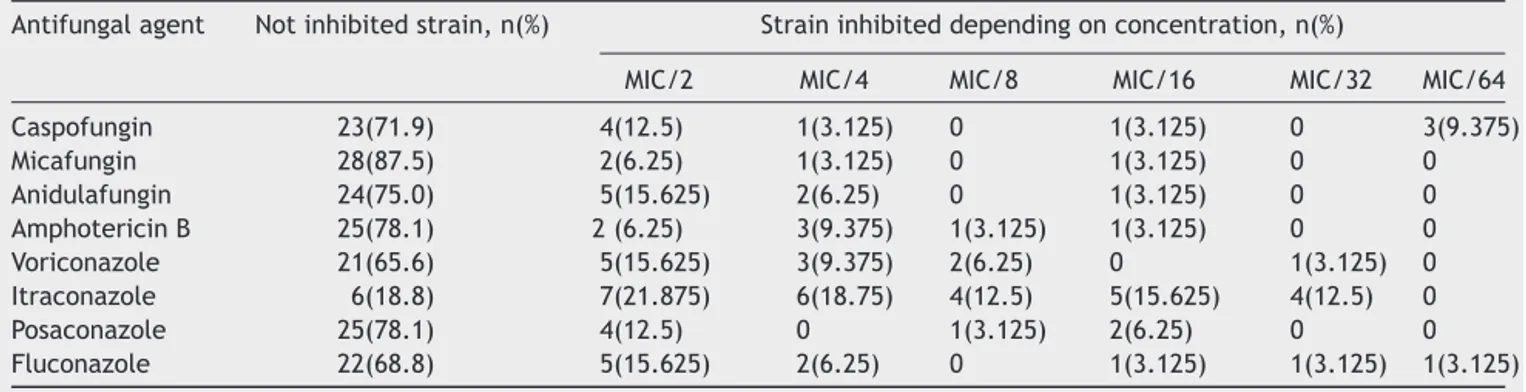

Biofilminhibitionexperiments

Table3showsthenumberofC.albicansstrainsinhibitedby differentantifungalagentsatsub-inhibitoryconcentrations. The concentration that inhibited biofilm formation 100% at needle-tips has been determined as biofilm inhibitory concentration (BIC). BIC results for echinocandins ranged from 0.0001 to 0.004g/ml for caspofungin, 0.001 to 0.004g/ml for micafungin, and 0.001 to 0.008g/ml for anidulafungin. The BIC range of amphotericin B was 0.03---0.25g/ml.

BIC ranges of the azoles were as follows:

0.0005---0.008g/ml for voriconazole, 0.06---0.015g/ml foritraconazole,0.002---0.008g/mlforposaconazole,and 0.004---0.06g/mlforfluconazole.

Most of the antifungal agents tested inhibited biofilm formation at similarproportions. Itraconazole completely inhibitedbiofilm formation inmore strains(26/32,81.3%;

p<0.05) than other antifungals. Micafungin showed sig-nificantlyless inhibition (4/32 strains)when compared to caspofungin, itraconazole, voriconazole, and fluconazole (p<0.05);howevernosignificantdifferencesamong anidu-lafungin,amphotericinB,andposaconazolewereobserved.

Discussion

The increased prevalence of biofilm-related infections in high-risk patients is a significant health concern. In our study, we detected biofilm formation in 90% of 162 C. albicansisolatesobtained fromblood cultures,whichis a higherrate than that observed in previous studies6,7,29,36.

The choice of assay may influence this finding, since

theChristensenmethodstainsdeadcells, livingcells,and theextracellularmatrix,whiletheXTTassayonlymeasures themetabolismoflivingcells.

Maturebiofilmsarecomplexstructurescontainingsessile cellswithdifferentmetabolicactivities42.Moreover,studies

haveshowndisagreementregardingthesignificant correla-tion between metabolic activity asmeasured by XTT and cellnumbersdeterminedbyothermethods11,22,23,34.

There-fore,previousdata,togetherwithourownfindings,prompt us to consider if comparing results obtained from differ-entassayscanaccuratelycharacterizebiofilmformationin thesestrains.

Plates with needle lids are frequently used to detect bacterial biofilms and their antimicrobial susceptibilities; however, few studiesutilizing thisapproachwithCandida

cells have been published10,28,30,41. Studies reported that

theoptimalcellnumberforCandidabiofilmformationwas 107CFU/ml,andsucrosesignificantlyincreasedC.albicans

biofilm formation onneedles23,30. Therefore,we adjusted

theyeastinoculatoMcFarland1(30×107CFU/mlfor

bacte-ria)anddilutedthesuspension1in30withgrowthmedium because yeast cells are larger in size than bacteria and fewcellsareneededforbiofilmformation8.Therefore,we

optimizedtheconditionsanddeterminedsignificantbiofilm usingtheCalgarymethod9.

In our study, the planktonic forms of all 30 extensive biofilm-forming isolates were susceptible to echinocan-dins and azoles as reported in previous epidemiological studies26,32.

Severalstudies haveinvestigatedtheeffectof flucona-zole on sessile C. albicans cells and found MBIC ranges of 4---1024g/ml2,3,25,27,28,34. In contrast, we found higher

MBIC50 and MBIC90 values (≥2048g/ml). Only few

stud-ieshavetested theeffectofitraconazoleonsessilecells. We observed similar MBIC values (1---128g/ml) as indi-cated in these studies13,27,28. The published MBIC range

for voriconazole is 0.5--->265g/ml20,27,37;however, only a

few studies have investigated the efficacy of posacona-zole on sessilecells20,43.Similarly toprevious results, we

found thatsessilecells wereresistanttovoriconazoleand posaconazole.

Table3 ProportionofC.albicansstrainsinhibitedbydifferentantifungalagentsatsub-inhibitoryconcentrations Antifungalagent Notinhibitedstrain,n(%) Straininhibiteddependingonconcentration,n(%)

MIC/2 MIC/4 MIC/8 MIC/16 MIC/32 MIC/64

Caspofungin 23(71.9) 4(12.5) 1(3.125) 0 1(3.125) 0 3(9.375) Micafungin 28(87.5) 2(6.25) 1(3.125) 0 1(3.125) 0 0 Anidulafungin 24(75.0) 5(15.625) 2(6.25) 0 1(3.125) 0 0 AmphotericinB 25(78.1) 2(6.25) 3(9.375) 1(3.125) 1(3.125) 0 0 Voriconazole 21(65.6) 5(15.625) 3(9.375) 2(6.25) 0 1(3.125) 0 Itraconazole 6(18.8) 7(21.875) 6(18.75) 4(12.5) 5(15.625) 4(12.5) 0 Posaconazole 25(78.1) 4(12.5) 0 1(3.125) 2(6.25) 0 0 Fluconazole 22(68.8) 5(15.625) 2(6.25) 0 1(3.125) 1(3.125) 1(3.125)

MIC:minimalinhibitoryconcentration.

The published amphotericin B MBIC range is 0.015---2g/ml2,3,28,37. We observed higher MBIC values

(4---128g/ml) and greater amphotericin B resistance

among our clinical isolates compared to data in the

aforementionedstudies.

Many studies have found that echinocandins

effec-tively inhibit C. albicans sessile cells at MBIC of

0.03---4g/ml of caspofungin, ≤0.03---2g/ml of micafun-gin,and0.015---16g/mlofanidulafungin3,17,18,20,24,37,38.We

determinedtheMBICranges forcaspofungin and micafun-gin as 0.125---16g/ml and ≤0.06---32g/ml, respectively. Althoughtheseoverallrangesaresimilartothosepublished inotherstudies,themaximumvaluesthatweobservedwere higher,withtheexceptionofanidulafungin17,20,38.

Althoughtherearenostandardbreakpointsforthe sus-ceptibilityofsessilecells,theMBICvaluesofechinocandins were partially within the planktonic susceptibility range of CLSI. Among the intense biofilm-forming and standard strains,11weresusceptibletocaspofungin,9were suscepti-bletoanidulafungin,and5weresusceptibletomicafungin. In addition, the MBIC50 of caspofungin was within the

therapeuticconcentrationrange(2g/ml)asindicatedby Cocuaudetal.5,andcaspofunginwaseffectiveagainst50%

oftheclinicalisolateswetested.

Overall,theMBICvaluesfoundinourinvestigationwere higherthanthosefoundinsomestudies2,4,10,13,17,28,34,37but

similar to others13,24,27,28,34. The higher MBIC values we

observedmaybeduetoour48-hbiofilmformationperiod, therelatively short24-h exposuretoeach antifungal,and the intense biofilm-forming capabilities of our strains. In addition,methodologicaldifferencesandtheisolationofour strainsfromblood,asopposedtootherculturesources,may besignificantfactors.

In our study, we compared MBIC/MIC ratios of the

antifungal agents to determine their efficacy on biofilm maintenancedirectly,whichhasnotbeenwidelyreported43.

TheloweststatisticallysignificantMBIC/MICratiowas deter-mined for amphotericinB,although theMBIC/MIC ratiois basedonplanktonicMICvalues.AlthoughtheMBIC/MICratio was low for amphotericin B, its MBIC values were above thesusceptibility rangesprovidedby CLSI,highlighting its ineffectiveness at therapeutic concentrations andtoxicity athighdosesininfectionsinvolvingplanktoniccells33.

VerylowplanktonicMICvaluesfoundforechinocandinsin ourstudyresultedinhigherMBIC/MICratioswhencompared

toamphotericin B. The importance of our finding is that theMBIC valuesof the echinocandinswere closest tothe planktonicsusceptibilitylimitsofCLSIcriteria.

Weexpectedazolestobelesseffectiveonsessilecells, buttheMBIC/MICratiooffluconazoleandvoriconazolewas >32000andhigherthananticipated.TheMBIC/MICratioof posaconazole wasonly 1536,echoing theresults of Tobu-dicetal.,whoreporteddecreasedefficacyofposaconazole duringallbiofilmphasesofC.albicans43.

Administering lower doses of antifungal agents over a longerperiodoftimein somehigh-risk patientgroups for treatmentorprophylaxisisofinterest,asbloodlevelsdrop belowclinicalsubinhibitory concentrations or invitro MIC values15,16. Todate, only afew studies have exploredthe

inhibitoryeffectofantifungalagentsonCandidabiofilm for-mationand with varying methodologies, such asenabling biofilm formation post-exposuretoan antifungalagent or co-incubatingthecellswithanantifungalagent1,16,24.Inour

study,C.albicanscellswereincubatedwithMIC/2---MIC/128 sub-MICsof each antifungal agent, andthe concentration thatinhibitedbiofilmformation100%atneedle-tipswasthe BIC.Weencounteredsomemethodologicaldifficulties,such as a fluctuating growth density observed in some strain-antifungal combinations, and instead measured the 100% biofilm inhibitory concentration. In general, total inhibi-tionwasseen close toMIC values(MIC/2 and MIC/4). We alsofound thatneedle lidswere notsuitable for measur-ingbiofilmformationinhibitionduetothefluctuantgrowth pattern of cells and difficulty in obtaining reproducible results.

The biofilm formation of some strains was not inhib-ited and sometimes increased close to the MIC of the antifungal agent. Schadow et al. first showed increased

Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm formation at sub-MIC values of rifampin19,35, and since then various

bacteria-antibioticcombinationshavebeenobserved19.Dose-effect

efficacy curvesof an agent areusually biphasic and cha-racterized by biofilm formation at low doses and biofilm inhibition at high doses. Some antibiotics act as antag-onists for biofilm formation at low or high doses but as agonistsat moderate doses.Similarly, we observed signif-icantinhibitionofbiofilmformationsub-MIClevelsinsome strain-antifungal combinationsbut less inhibition at some higher concentrations. This fluctuant growth pattern was seeninseveralyeast-echinocandincombinationsincontrast

toamphotericinBormostoftheazoles,withtheexception ofposaconazole.

Strain-specific factors may have influenced our study becausethiseffectwasnotseeninallstrains.Sub-inhibitory concentrationsofanantimicrobialagentoftencause phys-iologicalchangesinthemicroorganism,suchasstimulation orinhibitionofenzymeortoxin production15,16,45,47.

Simit-sopoulouetal.38reportedaparadoxicalincreaseinbiofilm

formation of C. albicans strains at concentrations higher thantheMIC,whichledtouncertaintyregardingtheability ofechinocandinstoreachsub-inhibitoryconcentrations in thebiofilms,inducechitinformation,andantifungal resis-tance.

Toourknowledge,nopreviousstudieshaveinvestigated

Candida biofilm capabilities using 8 different antifungal agents withthe Calgary method in the numberof strains used in our research. However, our methodology could

be improved by combining the BioTimer and Calgary

approachestoobtain earliertest resultsandenablemore timely clinical decision-making regarding prophylaxis and treatment. We also evaluated the use of needle lids to investigate inhibition of Candida biofilm formation and found that,despite itsease of use,this methoddoes not yieldreproducibleresultsduetofluctuantgrowthpatterns.

Thus, we recommend needle lids be combined with or

replacedbymethods thatmeasure metabolismor depend onthemorphologicalanalysisofthecells.

Ourresultsindicatethatechinocandinsaresuitablefor treating biofilm-related infections, and that itraconazole may be used for prophylaxis of such infections involving

C.albicans.Theincreasedprevalenceofbiofilm-associated fungal infections of C. albicans needs the development ofnewtreatment andprophylaxisstrategies,especiallyin high-riskpatients.Anantifungalabilitytolimitbiofilm for-mationshouldbeconsideredwhenselectinganappropriate agent. In addition, even agents effective at sub-MIC lev-elscouldleadtoantifungalresistanceandshouldbeused judiciously16.Therefore,furtherinvivoandinvitrostudies

exploringtheuseofsub-MICsofantifungalagentsin prophy-laxisstrategiesandtheapplicationofstandardizedbiofilm measurementmethodsareneededtodeterminetheunique dosageandexposuretimeofanantifungalforitsmaximum anti-biofilmeffectivenessandpatientsafety.

Ethical

disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects.The authors

declarethat the proceduresfollowed were in accordance withtheregulationsoftherelevantclinicalresearchethics committeeandwiththoseoftheCodeofEthicsoftheWorld MedicalAssociation(DeclarationofHelsinki).

Confidentialityofdata.Theauthorsdeclarethattheyhave

followedtheprotocolsoftheirworkcenteronthe publica-tionofpatientdata.

Right to privacy and informed consent.The authors

declarethatnopatientdataappearinthisarticle.

Conflict

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarethattheyhavenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgments

Thisstudy wasapprovedbytheBaskentUniversity Institu-tionalReview Board(Projectno:KA13/150).Ourresearch was supported by the Baskent University Research Fund, AstellasPharma/Japan(micafungin),MerckSharp&Dohme Corp./USA (caspofungin, posaconazole), and Pfizer/USA (anidulafungin).

References

1.BruzualI,RiggleP,HadleyS,KumamotoCA.Biofilmformation byfluconazole-resistantCandidaalbicansstrainsisinhibitedby fluconazole.JAntimicrobChemother.2007;59:441---50.

2.ChandraJ,Kuhn DM,Mukherjee PK,Hoyer LL,McCormickT, GhannoumMA.Biofilmformationbythefungalpathogen Can-didaalbicans:development,architecture,anddrugresistance. JBacteriol.2001;183:5385---94.

3.ChoiHW,ShinJH,JungSI,ParkKH,ChoD,KeeSeJ,ShinMG, SuhSP, RyangDW.Species-specificdifferences inthe suscep-tibilitiesofbiofilmsformedbyCandida bloodstreamisolates to echinocandin antifungals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1520---3.

4.ChristensenGD,SimpsonWA,YoungerJJ,BaddourLM,Barrett FF,MeltonDM,BeacheyEH.Adherenceofcoagulase-negative staphylococci to plastic tissueculture plates: a quantitative modelfortheadherenceofstaphylococcitomedicaldevices.J ClinMicrobiol.1985;22:996---1006.

5.CocuaudC,RodierM-H,DaniaultG,ImbertC.Anti-metabolic activityofcaspofunginagainstCandida albicansand Candida parapsilosisbiofilms.JAntimicrobChemother.2005;56:507---12.

6.DagI,KirazN,OzY.Evaluationofdifferentdetectionmethods ofbiofilmformationinclinicalCandidaisolates.AfrJMicrobiol Res.2010;4:2763---8.

7.Demirbilek M, Timurkaynak F, Can F, Azap Ö. Biofilm pro-duction and antifungal susceptibility patterns of Candida

species isolated from hospitalized patients. Mikrobiyol Bult. 2007;41:261---9.

8.Grant-bio,Densitometer,DEN-1Operatinginstructions,Version 3---April2011.(http://www.ankyralab.com/images/products/ DEN1en.pdf)[accessed06.07.14].

9.Harrison H. Applications D. Instructions. The MBEC, High-throughput (HTP) assay. Innovotech1-16 http:// www.innovotech.ca/MBECHTPInstructionsRev1.pdf[accessed 06.07.14].

10.HarrisonJJ, Turner RJ, Ceri H. A subpopulation of Candida albicansandCandidatropicalisbiofilmcellsarehighlytolerant tochelatingagents.FEMSMicrobiolLett.2007;272:172---81.

11.HawserS.AdhesionofdifferentCandidaspp.toplastic:XTT formazandeterminations.JMedVetMycol.1996;34:407---10.

12.HawserSP, DouglasLJ.Biofilm formationbyCandidaspecies onthesurface ofcathetermaterials invitro. Infect Immun. 1994;62:915---21.

13.HawserSP,DouglasLJ.ResistanceofCandidaalbicansbiofilms to antifungal agents in vitro. AntimicrobAgents Chemother. 1995;39:2128---31.

14.HazenKC,HowellSA.Candida,Cryptococcus,andotheryeasts ofmedicalimportance.In:MurrayPR,editor.Manualof clini-calmicrobiology.9thed.Washington,DC:ASMPress;2007.p. 1762---88.

15.HazenKC,MandellG,ColemanE,WuG.Influenceoffluconazole at subinhibitoryconcentrations on cell surface hydrophobic-ityandphagocytosisofCandidaalbicans.FEMSMicrobiolLett. 2000;183:89---94.

16.HenriquesM,CercaN,AzeredoJ,OliveiraR.Influenceof sub-inhibitory concentrations of antimicrobial agents on biofilm

formationin indwelling medical devices. Int J Artif Organs. 2005;28:1181---5.

17.JacobsonMJ, Piper KE, Nguyen G, Steckelberg JM,Patel R. In vitro activity of anidulafungin against Candida albicans

biofilms.AntimicrobAgentsChemother.2008;52:2242---3.

18.JacobsonMJ,SteckelbergKE,PiperKE,SteckelbergJM,Patel R.Invitroactivity ofmicafunginagainstplanktonicand ses-sileCandidaalbicansisolates.AntimicrobAgentsChemother. 2009;53:2638---9.

19.Kaplan JB. Antibiotic-induced biofilm formation. Int J Artif Organs.2011;34:737---51.

20.KatragkouA,ChatzimoschouA,SimitsopoulouM,Dalakiouridou M,Diza-MataftsiE,Tsantali C,RoilidesE. Differential activi-tiesofnewerantifungalagentsagainstCandida albicansand

Candidaparapsilosis biofilms. AntimicrobAgents Chemother. 2008;52:357---60.

21.Krzy´sciak P. Quantitative evaluation of biofilm formation in yeast nitrogen base (YNB) broth and in bovine serum (BS) ofCandida albicansstrainsisolatedfrom mucosalinfections. Wiadomo´sciParazyto.2011;l57:107---10.

22.Kuhn DM, Balkis M, Chandra J, Mukherjee PK, Ghannoum MA. Uses and limitations of the XTT assay in studies of

Candida growth and metabolism. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41: 506---8.

23.KuhnDM,ChandraJ,MukherjeePK,GhannoumMA.Comparison ofbiofilmsformedbyCandidaalbicansandCandidaparapsilosis

onbioprostheticsurfaces.InfectImmun.2002;70:878---88.

24.KuhnDM,GeorgeT,ChandraJ,MukherjeePK,GhannoumMA. AntifungalsusceptibilityofCandidabiofilms:uniqueefficacyof amphotericinBlipidformulationsandechinocandins. Antimi-crobAgentsChemother.2002;46:1773---80.

25.LamfonH, Porter SR, McCullough M, Pratten J. Susceptibil-ity of Candida albicans biofilms grown in a constant depth film fermentor to chlorhexidine, fluconazole and micona-zole:a longitudinalstudy.JAntimicrobChemother.2004;53: 383---5.

26.LockhartSR, IqbalN,ClevelandAA, FarleyMM, HarrisonLH, BoldenCB, BaughmanW, SteinB,HollickR, ParkBJ,Chiller T.Speciesidentificationandantifungalsusceptibilitytestingof

Candida bloodstreamisolatesfrom population-based surveil-lance studies in two U.S. cities from 2008 to 2011. J Clin Microbiol.2012;50:3435---42.

27.NwezeEI, Ghannoum A, Chandra J,Ghannoum MA, Mukher-jeePK.Developmentofa96-wellcatheter-basedmicrodilution methodtotestantifungalsusceptibilityofCandidabiofilms.J AntimicrobChemother.2012;67:149---53.

28.Onurda˘gFK,ÖzgenS,Abbaso˘gluU,Gürcan ˙IS.Comparisonof twodifferentmethodsfortheinvestigationofinvitro suscep-tibilitiesofplanktonicandbiofılmformingCandidaspeciesto antifungalagents.MikrobiyolBul.2010;44:619---31.

29.PannanusornS,FernandezV,RömlingU.Prevalenceofbiofilm formationinclinicalisolatesofCandidaspeciescausing blood-streaminfection.Mycoses.2013;56:264---72.

30.ParahitiyawaNB, SamaranayakeYH, SamaranayakeLP, YeJ, TsangPWK,CheungBPK,YauJYY,YeungSKW.Interspecies vari-ationinCandida biofilmformationstudied using theCalgary biofilmdevice.APMIS.2006;114:298---306.

31.PeetersE,NelisHJ,CoenyeT.Comparisonofmultiple meth-odsforquantificationofmicrobialbiofilmsgrowninmicrotiter plates.JMicrobiolMethods.2008;72:157---65.

32.PfallerMA,MesserSA,WoosleyLN,JonesRN,CastanheiraM. Echinocandinandtriazoleantifungalsusceptibilityprofilesfor

clinicalopportunisticyeast and moldisolatescollectedfrom 2010to2011:applicationofnewCLSIclinicalbreakpointsand epidemiologicalcutoffvaluesforcharacterizationofgeographic andtemporaltrendsofantifungalresistance.JClinMicrobiol. 2013;51:2571---81.

33.RamageG,VandewalleK,BachmannSP,WickesBL,LoL.Invitro pharmacodynamicpropertiesofthreeantifungalagentsagainst preformed Candidaalbicansbiofilmsdetermined bytime-kill studies.AntimicrobAgentsChemother.2002;46:3634---6.

34.RamageG,WalleKVA,WickesBL,LoL.Standardizedmethod forinvitroantifungalsusceptibilitytestingofCandidaalbicans

biofilms.AntimicrobAgentsChemother.2001;45:2475---9.

35.Schadow KH, Simpson WA, Christensen GD. Characteristics of adherence to plastic tissue culture plates of coagulase-negativestaphylococciexposedtosubinhibitoryconcentrations ofantimicrobialagents.JInfectDis.1988;157:71---7.

36.ShinJH,KeeSJ,ShinMG,KimSH,ShinDH,LeeSK,SuhSP,Ryang DW.BiofilmproductionbyisolatesofCandidaspecies recov-eredfromnonneutropenicpatients:comparisonofbloodstream isolates with isolates from other sources. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1244---8.

37.ShufordJA,PiperKE,SteckelbergJM,PatelR.Invitrobiofilm characterization and activity of antifungal agents alone and incombinationagainstsessileandplanktonicclinicalCandida albicansisolates.DiagnMicrobiolInfectDis.2007;57:277---81.

38.SimitsopoulouM,PeshkovaP,TasinaE,KatragkouA, Kyrpitzi D,VelegrakiA,WalshTJ,RoilidesE.Species-specificand drug-specific differences in susceptibility of Candida biofilms to echinocandins:characterization oflesscommon bloodstream isolates.AntimicrobAgentsChemother.2013;57:2562---70.

39.SoustreJ,RodierM-H,Imbert-BouyerS,DaniaultG,ImbertC. CaspofunginmodulatesinvitroadherenceofCandidaalbicans

toplasticcoatedwithextracellularmatrixproteins.J Antimi-crobChemother.2004;53:522---5.

40.StepanovicS,Vukovic D,DakicI,Savic B,Svabic-VlahovicM. Amodifiedmicrotiter-platetestforquantificationof staphylo-coccalbiofilmformation.JMicrobiolMethods.2000;40:175---9.

41.ThysS[PhDthesis]Effectofbiosurfactantsisolatedfrom endo-phytesonbiofilmformationbyCandidaalbicans.Universityof Gent;2009.

42.Tobudic S, Kratzer C, Lassnigg A, Presterl E. Antifun-gal susceptibility of Candida albicans in biofilms. Mycoses. 2012;55:199---204.

43.TobudicS,LassniggA,KratzerC,GraningerW,PresterlE. Anti-fungalactivityofamphotericinB,caspofunginandposaconazole onCandidaalbicansbiofilmsinintermediateandmature devel-opmentphases.Mycoses.2009;53:208---14.

44.Ustac¸elebiS¸,MutluG, ImirT, CengizAT,Tünmay E,Mete Ö. Candidatürler.In:TemelveKlinikMikrobiyoloji.Ankara:Günes¸ Kitabevi;1999.p.1081---6.

45.Walker LA, Munro CA, de Bruijn I, Lenardon MD, McKin-non A, Gow NAR. Stimulation of chitin synthesis rescues

Candida albicans from echinocandins. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000040.

46.ClinicalandLaboratoryStandardsInstitute.Referencemethod for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. 3rded.Wayne,PA:ClinicalandLaboratoryStandardsInstitute; 2008.M27-A3.

47.Wu Q, Wang Q, Taylor KG, Doyle RJ, Wu Q, Wang QI. Subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics affect cell sur-face properties of Streptococcus sobrinus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1399---401.