https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-019-00249-2 RESEARCH PAPER

The GUSS test as a good indicator to evaluate dysphagia in healthy

older people: a multicenter reliability and validity study

Ebru Umay1 · Sibel Eyigor2 · Ali Yavuz Karahan3 · Ilknur Albayrak Gezer4 · Ayse Kurkcu4 · Dilek Keskin5 ·

Gulten Karaca5 · Zeliha Unlu6 · Canan Tıkız6 · Meltem Vural7 · Banu Aydeniz7 · Ebru Alemdaroglu8 · Emine Esra Bilir8 ·

Ayse Yalıman9 · Ekin Ilke Sen9 · Mazlum Serdar Akaltun10 · Ozlem Altındag10 · Betul Yavuz Keles11 · Meral Bilgilisoy12 ·

Zeynep Alev Ozcete13 · Aylin Demirhan13 · Ibrahim Gundogdu1 · Murat Inanir14 · Yalkin Calik15

Received: 12 July 2019 / Accepted: 26 September 2019 / Published online: 9 October 2019 © European Geriatric Medicine Society 2019

Key summary points

Aim We aimed to evaluate whether the Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS) test is an effective method for evaluating swal-lowing difficulty in healthy older people.

Findings Total GUSS score sensitivity was 95.5% and its specificity was 94.4%.

Message The GUSS test is a valid and reliable test to identify possible oropharyngeal dysphagia risk in healthy older person who had no secondary dysphagia. It is suitable as a screen test for clinical practice.

Abstract

Purpose Dysphagia is known to be a disorder of the swallowing function, and is a growing health problem in aging popula-tions. Swallowing screening tests have mostly been studied in comorbidities such as stroke associated with old age. There is no simple, quick and easy screening test to best determine the risk of oropharyngeal dysphagia in geriatric guidelines. We aimed to evaluate whether the Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS) test is an effective method for evaluating swallowing difficulty in healthy older people.

Methods This cross-sectional and multicenter study was conducted at 13 hospitals between September 2017 and February 2019. The study included 1163 participants aged ≥65 years and who had no secondary dysphagia. Reliability was evaluated for data quality, scaling assumptions, acceptability, reliability, and validity as well as cutoff points, specificity and sensitivity.

* Ebru Umay

ebruumay@gmail.com

1 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinic, Ankara Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Training and Research Hospital, University of Health Sciences, Altindag, Ankara, Turkey

2 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Ege University, Izmir, Turkey

3 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Usak University, Usak, Turkey

4 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Selcuk University, Konya, Turkey

5 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Kırıkkale University, Kirikkale, Turkey

6 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Celal Bayar University, Manisa, Turkey

7 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Bakırköy Dr. Sadi Konuk Training and Research Hospital, University of Health Sciences, Istanbul, Turkey

8 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Ankara Training and Research Hospital, University of Health Sciences, Ankara, Turkey

9 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey

10 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Gaziantep University, Gaziantep, Turkey

11 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Istanbul Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey 12 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Antalya

Training and Research Hospital, Antalya, Turkey

13 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Izmir Tepecik Training and Research Hospital, Izmir, Turkey 14 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Kocaeli

University, Kocaeli, Turkey

15 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Bolu Izzet Baysal Training and Research Hospital, Bolu, Turkey

Results The age distribution of 773 (66.5%) patients was between 65 and 74 years and 347 (29.8%) of them were male and 767 (66%) patients were female. The average total GUSS score was 18.57 ± 1.41. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.968. There was a moderate statistically significant negative correlation between the total GUSS and 10-item Eating Assessment Tool scores as well as between the total GUSS score and quality of life. The cutoff point of the total GUSS score was 18.50, sensitivity was 95.5% and specificity was 94.4%.

Conclusions The GUSS test is a valid and reliable test to identify possible oropharyngeal dysphagia risk in healthy older people who had no secondary dysphagia. It is suitable as a screen test for clinical practice.

Keywords Dysphagia · Older people · Screen test · GUSS

Introduction

Dysphagia is known to be a disorder of the swallowing function, and is a growing health problem in aging popu-lations [1]. The incidence of secondary dysphagia in hos-pitalized older patients is reported as being between 33 and 68%, but this rate is reported to be as high as 90% depending on the evaluation method used [1, 2]. On the other hand, the prevalence of dysphagia in healthy older individuals, known as presbyphagia that defined as the age-related changes in all phases of swallowing, is not certain. Although some studies have reported that the prevalence of presbyphagia in independently living older people was between 11 and 33.7%, the true prevalence is not known because validity and reliability of the tests were not known in these studies [3, 4].

Studies have reported that most cases of pneumonia in the older people are aspiration pneumonia [5, 6]. Aspiration pneumonia is related to changes in anatomic, physiologi-cal, and neural functions affecting swallowing with aging or neurological/non-neurological diseases causing secondary dysphagia [7]. The age-related changes in healthy older peo-ple are often silent, progress slowly and usually occur gradu-ally over time without any obvious symptoms as part of the general aging process [5–8]. Therefore, older individuals try to overcome their difficulty in swallowing with various adaptation mechanisms, such as reducing the amount of food consumed, prolonging meal times and avoiding problem-atic food intake, as well as preferring food of a different consistency. It has been reported that these compensatory mechanisms occur over weeks or even months and people are unaware of this dysfunction and behavioral change [9]. Therefore, this lack of awareness relating to swallowing dys-function also creates an extra risk for dysphagia. Moreover, malnutrition due to reduction and change in food intake may trigger or promote the fragility process in older people.

Consequently, screening older people for presbyphagia is crucial to avoid complications of swallowing dysfunc-tion, such as aspiradysfunc-tion, and especially silent aspiration. Bedside screening tools and instrumental assessments are usually used for the diagnosis of oropharyngeal dysphagia

(OD). Researchers have frequently used various question-naire screening tests including aspiration findings/symp-toms and the water swallow test in dysphagia studies among healthy older people [3, 10–14]. On the other hand, it has been reported that the feeding habits of older people change with increasing age and this leads to aspiration. Therefore, early detection prior to aspiration is essential. However, in the guidelines, there is currently no simple, quick and easy method to determine OD risk in healthy geriatric people [15–17].

Videofluoroscopy (VF) and endoscopic evaluation are gold standard methods for dysphagia evaluation, but both have disadvantages such as failure to directly show the swal-lowing and anatomy, risk of exposure to serious radiation for VF; and endoscopy does not show aspiration directly as well as both require skilled personnel and special equipment. Therefore, they cannot be used as screening method.

Some screening tests such as 10-item Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) and volume viscosity swallow test (VVST) are used for older people [18, 19]. While the EAT-10 is used to assess dysphagia symptoms and symptom severity, VVST is used to evaluate the ability of swallowing. The VVST is applied with three different volumes (5, 10 and 20 ml) and three different viscosities (liquid, mildly thick and extreme spoon-thick) [20]. Although VVST is used for elderly patients, it is not sufficient to identify presbyphagia as it is not applied with solid food, in fact dysphagia due to the difficulty of eating solid food has been reported frequently in this age group [21].

On the other hand, the Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS) test is a simple, cheap and non-invasive tool includ-ing three different consistencies of food (solid, semisolid and liquid) and various amounts of food similar to those taken in daily life [22]. Although its efficacy has not been reported in healthy elderly, the sensitivity and specificity were reported to be high in validity and reliability studies concerning stroke events that occur with aging [22–30].

Therefore, in this study, it was aimed to evaluate whether GUSS is an effective method for evaluating swallowing dif-ficulty in healthy older people who have no disease causing secondary dysphagia.

Materials and methods

Study design

This cross-sectional and multicenter study was conducted at 13 hospitals. The study included 1163 participants aged ≥ 65 years who were fed orally and had been admitted to physical medicine and rehabilitation (PMR) outpatient because of musculoskeletal disorders complaints such as osteoporosis, degenerative osteoarthritis, low back and neck pain between September 2017 and February 2019.

Institutional approval was received at each participating hospital before ethic approval. Later, all approvals were merged and one approval was obtained by the local Insti-tutional Ethics Committee of center hospital (University of Health Sciences, Ankara Diskapi Training and Research Hospital) of the first author (E.U.). All participants or the relatives participants who are illiterate provided written informed consent and the study was conducted in accord-ance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. Participants

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to rule out structural, functional and/or cognitive impair-ments/diseases and secondary dysphagia that could affect swallowing functions.

Inclusion criteria Participants

– Aged ≥ 65 years

– Who could tolerate the sitting position

– Who had sufficient cognitive skills to be able to cooper-ate with test items (mini-mental test > 20)

– Who had communication ability

Exclusion criteria

– Any history of pneumonia requiring hospitalization, – The presence of known secondary dysphagia – Speech disorders such as aphasia

– Restricted cooperation and communication

– Any previous history of head and neck surgery, malignancy – Severe dental disease

– Serious psychiatric disorders – Severe kidney and/or liver failure

– Any severe gastrointestinal system disorder

– Progressive (such as Parkinson and Alzheimer disease) and non-progressive (such as stroke and traumatic/non-traumatic brain injury) neurologic diseases

– Severe respiratory disease that could affect swallowing function

Of the 1176 participants initially enrolled in the study, 13 were excluded because of insufficient cooperation. Forty-five participants were evaluated for inter-rater reliability by 2 independent raters. One thousand one hundred and sixty-three participants were tested for characteristics of scale, internal consistency and validity. Receiver-Operating Char-acteristics (ROC) of scale for sensitivity and specificity were applied to 269 participants from one center to determine the accuracy of the endoscopic evaluation.

Demographics

Participants’ demographics including age, gender, education duration and additional comorbidities were all recorded and Charlson comorbidity index score was calculated between 0 and 8.

Instruments

The EAT-10 was used to assess dysphagia symptoms and the severity of participants along with the risk of OD. This tool is a self-administered, symptom-specific outcome instru-ment consisting of 10 questions dealing with dysphagia symptoms. Each question score ranges from 0 (no problem) to 4 (severe problem) and participants who score ≥ 3 are con-sidered to be at ‘high risk’ of OD.

Swallowing-related quality of life scale (Swal-QoL) was used to evaluate the impact of OD on their quality of life. It contains 44 questions on domains of eating disorder, dura-tion of eating, desire to eat, choice of meal, communicadura-tion, mental health, anxiety, social functioning, fatigue, and sleep. Each question is evaluated with a score from 1 (the worst) to 5 (the best) points. Each domain can be evaluated separately. In our study, total scoring was used.

Katz Daily Living Activities Index (KDLAI) was per-formed to evaluate independence in daily activities. It is used in the treatment and prognosis assessment of chronic dis-eases as well as in the older people. In six sub-sections, the participants are assessed for their ability to independently perform functions related to bathing, dressing, toiletries, transportation, intestinal bladder control and feeding. The total score is between 1 and 6.

Gugging Swallowing Screen test (GUSS)

The GUSS test includes two sections: the first section being the indirect swallowing trial, while the second section is the direct swallowing trial [22]. The indirect swallowing trial is scored as yes/no (0–1) or between 0 and 2 points with a maxi-mum of 5 points. The second section of the test assesses the

direct swallowing trial with different types of food consist-ency. The evaluation criteria include deglutition, involuntary cough, drooling and voice changes with the intake of liquid, semisolid and finally solid food. The second section of the test is valued over a maximum 15 points with a maximum of 5 points for each group with higher points indicating successful swallowing. Twenty points are the highest score that a patient can attain. In total, 4 levels of severity can be determined as follows: 0–9 points: severe OD and high aspiration risk; 10–14 points: moderate OD and moderate risk of aspiration; 15–19 points: mild OD with mild aspiration; 20 points: nor-mal swallowing. The test also allows for diet recommenda-tions according to the scores obtained by the patients.

Previously, GUSS was proven to be a valid and reliable swallowing screening tool among dysphagic stroke patients in a study performed in various countries including our own [22–25, 27, 28]. Before the study, the GUSS test was taught to each center in our country by specialists who demon-strated its validity and reliability.

Characteristics of the scale

Missing data, computable and items scores, a coefficient of variation, floor and ceiling effects, and skewness of the data were all determined.

Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha, 95% confidence intervals (CI), Cronbach’s alpha when one item is deleted and corrected, item-to-total correlations were used to assess internal consistency.

Inter-rater reliability studies were conducted. Forty-five participants were assessed by two independent raters within 2 h. Agreement between the two independent raters was ana-lyzed using Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC). Validity

The validity was evaluated by construct (factorial, conver-gent and diverconver-gent) validity. Initially, sampling adequacy was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Exploratory and confirma-tory factor analysis was conducted. Convergent validity was performed using the EAT-10 scale. Divergent validity was tested by the Swal-QoL and KDLAI scales.

Receiver‑operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of scale for specificity and sensitivity

Two hundred and sixty-nine participants admitted to the first center were evaluated to calculate specificity and sensitivity of the test. Flexible fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation (FEES) was applied in the first center by the same specialist as this

evaluation requires special equipment and skilled person-nel as well as based on interpretation. T-GUSS total scores were compared with the FEES results. Then, cutoff points, specificity and sensitivity were calculated.

Flexible fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES)

Endoscopic evaluation of participants was performed in the 90° sitting position, using a non-ducted fiberoptic nasopharyngoscope of 3.4 mm diameter, a light source, camera, monitor, and DVD recorder. To determine resi-due, aspiration or penetration, water, yoghurt and a piece of biscuit were used as liquid, semisolid and solid foods. The findings were recorded as video images and exam-ined to determine the dysphagia levels of participants with the Dziewas endoscopic evaluation scale with a score of between 1 and 6 [31]. Score 1 was considered as “normal swallowing function” while scores 2–6 were considered as “dysphagia”.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using R Software (www.R-proje ct.org) and STATA. Descriptive statistics were demonstrated as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as a percentage (%) for nomi-nal variables. The following psychometric properties of the scale were assessed according to Nunnally and Bern-stein, and missing data (%), computable scores (%) item mean ± SD scores, a coefficient of variation, floor and ceiling effects, and skewness of the data were all identi-fied [32]. Internal consistency was measured using Cron-bach’s alpha and 95% CI, ‘CronCron-bach’s alpha when one item is deleted’, and corrected item-to-total correlations. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70 or higher and an item-to-total correlation of 0.30 and/or higher were considered to indicate adequate reliability. Inter-rater reliability was estimated using ICC for the total GUSS score. Accord-ing to the ICC results, positive values rangAccord-ing from 0 to 0.2 indicated poor agreement; 0.2–0.4 indicated fair agreement; 0.4–0.6 indicated moderate agreement; 0.6–0.8 indicated good agreement; and 0.8–1 indicated very good agreement. The validity was evaluated by construct (factorial, convergent and divergent) validity. Initially sampling adequacy was evaluated using the Kai-ser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity [33]. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to examine whether a single factor could be identified, a one-factorial confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for categorical data was used to test whether each set of items measured a single unidimensional construct.

The Comparative Fit Index (CFI: > 0.90 acceptable, > 0.95 excellent) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approxi-mation (RMSEA: < 0.08 acceptable, < 0.05 excellent) were used as goodness-of-fit statistics. Spearman’s rank or Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated for convergent and divergent validity. Convergent validity was evaluated by correlation between the EAT-10 and total GUSS scores, and divergent validity was assessed by correlations between Swal-QoL and KDLAI scores. Correlation coefficients were classified and 0.70–1.0 was considered as high, 0.30–0.69 as moderate, and < 0.30 as low. Specificity and sensitivity in ROC analysis were calculated at various cutoff points. p < 0.05 values were accepted as statistically significant.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

A total of 1176 participants were evaluated during the study. After application of the exclusion criteria, 13 par-ticipants were excluded. A total of 1163 parpar-ticipants were enrolled in the present study. Participants’ characteristics are shown in Table 1.

The age distribution of all participants was as fol-lows; 773 (66.5%) participants were aged between 65 and 74 years, 347 (29.8%) participants between 75 and 84 years, and 43 (3.7%) participants aged ≥85 years. A total of 396 (34%) participants were male and 767 (66%) were female.

Characteristics of the GUSS test

All participants (n:1163) completed the data quality, inter-nal consistency and validity tests. Inter-rater reliability was assessed in 45 participants, specificity and sensitivity of the test was evaluated in 269 patients.

Data quality

The application rate of the GUSS test was 100%. The per-centage of missing data was zero for items and the percent-age of computable scores was full.

The mean of item scores was lowest and highest scores between 3.93 ± 0.32 (indirect trial) and, 4.98 ± 0.20 (semi-solid trial). The coefficient of variation ranged from 40.5 (liquid trial) to 44.2 (indirect trial). Skewness of the data ranged from 0.920 (semisolid trial) to 0.427 (indirect trial). The inter-item correlations and corrected item-to-total correlations were between 0.483 and 0.946, and 0.687 (indirect trial) and 0.879 (solid trial), respectively (Tables 2, 3). Tables 2 and 3 were considered to indicate adequate reliability.

Table 1 Participants’ characteristics

SD standard deviation, EAT-10 10-item eating assessment tool, GUSS Gugging Swallowing Screen test, Swal-Qol swallowing-related qual-ity of life scale, KDLAI Katz Daily Living Activities Index

Variables Participants (n = 1163)

Age n(%)

Between 65 and 74 years 773 (66.5) Between 75 and 84 years 347 (29.8)

≥ 85 years 43 (3.7) Gender n(%) Male 396 (34.0) Female 767 (66.0) Education duration n(%) Illiterate 2 (0.2) 5 years 282 (24.2) 8 years 742 (63.8) 11 years 82 (7.1)

More than 11 years 55 (4.7) Charlson comorbidity index (0–8) 2.57 ± 1.14 EAT-10 (0–40) mean ± SD 2.39 ± 2.11 Total GUSS score (0–20) mean ± SD 18.57 ± 1.41 Swal-QoL (0–100) mean ± SD 132.17 ± 31.54 KDLAI (1–6) mean ± SD 5.64 ± 1.20

Table 2 Descriptive characteristics of the scale of participants

Target population: 1163 participants SD standard deviation

Mean ± SD Coefficient of

variation Corrected item-to-total correlation Cronbach’s α if item deleted

Indirect trial (0–5) 3.93 ± 0.32 44.2 0.687 0.919

Semisolid trial (0–5) 4.98 ± 0.20 42.1 0.711 0.907

Liquid trial (0–5) 4.94 ± 0.35 40.5 0.834 0.951

Solid trial (0–5) 4.92 ± 0.43 42.4 0.879 0.958

Acceptability

The average total GUSS score was 18.57 ± 1.41. While the floor was not determined, the ceiling effects were 40.7%. The Cronbach’s alpha was high (0.968).

Reliability

An intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the total GUSS score was calculated for inter-rater reliability in 45 participants. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was 0.892 (95% CI 0.815–0.921) for the total GUSS score and indicated very good agreement.

Validity

The KMO test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity showed that the data were adequate for factorial analysis (0.805 and

p < 0.001, respectively). An EFA of the items revealed a

sin-gle factor explaining 73.1% of variance with factor loadings in the range of 0.618–0.933. The goodness-of-fit statistics for the one-factorial CFA were TLI = 0.901, CFI = 0.912 and RMSEA = 0.078 for a single factor.

Convergent validity demonstrated statistically significant moderate negative correlation between the total GUSS and EAT-10 scores (r: − 0.425, p < 0.001).

There was a statistically significant moderate correlation between the total GUSS test score and Swal-QoL (r: 0.413,

p = 0.001), and KDLAI (r: 0.444, p = 0.001) scores as

diver-gent validity (Table 4).

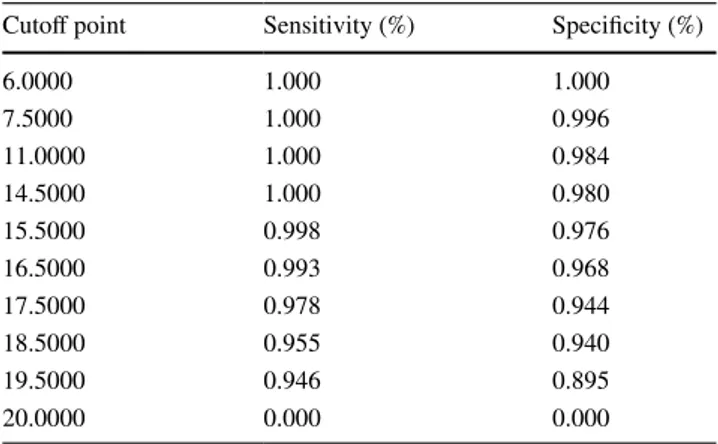

Receiver‑operating characteristics (ROC) analysis for specificity and sensitivity

While 198 (73.6%) of the 269 (73.6%) participants scored 1 point (normal swallowing) in endoscopic dysphagia level determined by Dziewas for FEES, 71 (26.4%) participants scored between 2 and 6 points (dysphagic). The cutoff point of the total GUSS test scores according to the endoscopic dysphagia severity level (normal or dysphagic) is presented in Table 5. The optimal cutoff point was 18.5 for GUSS test to predict the risk of dysphagia. Using this cutoff point, sen-sitivity and specificity were 95.5% and 94.4%, respectively.

Discussion

To diagnose the risk of aspiration in older people, it is nec-essary to clearly define fast, easy, cheap and non-invasive screen tests which can be administered by clinicians without specialized training. In addition, screening tests are vital to prevent potential complications of dysphagia in older peo-ple and to provide necessary care and treatment. Actually, given the high prevalence in hospitalized geriatric patients, dysphagia assessment should probably be generalized to

Table 3 Inter-item correlation matrix

Target population: 1163 participants

Indirect trial Semisolid trial Liquid trial Solid trial Direct trial

Indirect trial 1.000 0.506 0.544 0.483 0.536

Semisolid trial 0.506 1.000 0.844 0.796 0.927

Liquid trial 0.544 0.844 1.000 0.845 0.903

Solid trial 0.483 0.796 0.845 1.000 0.946

Direct trial 0.536 0.927 0.903 0.946 1.000

Table 4 Correlation coefficients of the total score of the GUSS with validity parameters

Target population: 269 participants

CI correlation interval, min–max minimum–maximum, Eat-10 10-item eating assessment tool, Swal-Qol swallowing-related quality of life scale, KDLAI Katz Daily Living Activities Index

Correlation

coefficient 95% CI (min–max) p EAT-10 (0–40) − 0.425 0.128–0.541 < 0.001 Swal-Qol (0–100) 0.413 0.097–0.618 0.001

KDLAI (1–6) 0.444 0.221–0.635 0.001

Table 5 Coordinates of the ROC curve analysis

Normal (1 point) and dysphagic (between 2 and 6 points) status according to the dysphagia level that evaluated with FEES are based on. Target population: 269 participants

ROC receiver-operating characteristics

Cutoff point Sensitivity (%) Specificity (%)

6.0000 1.000 1.000 7.5000 1.000 0.996 11.0000 1.000 0.984 14.5000 1.000 0.980 15.5000 0.998 0.976 16.5000 0.993 0.968 17.5000 0.978 0.944 18.5000 0.955 0.940 19.5000 0.946 0.895 20.0000 0.000 0.000

every older patient, but it is still not happening in all geriat-ric departments routinely. To generalize such an assessment, an easy screening tool is, therefore, crucial so that it can be correctly applied by all health care professionals.

Studies from a systematic review and meta-analysis, including hospitalized older patients with secondary dys-phagia, have revealed that the water-swallowing test, stand-ardized swallowing assessment, GUSS and Toronto Bed-side Swallowing Screen tests have been reported to have the highest psychometric performance [34]. Similar studies with hospitalized older patients have shown that the VVST had a sensitivity value of between 87.0 and 88.2% and a specificity value of between 64.7 and 81.0% to identify impaired safety in swallowing [18, 35].

In healthy older individuals, there is no ideal test for the diagnosis of dysphagia. The questionnaire screen tests describing the severity of dysphagia symptoms and OD risk had been used in previous studies. Their sensitivity and specificity values were between 77 and 90% and between 67.5 and 89%, respectively [10, 11, 26, 27]. However, when considering these sensitivity and specificity results, it is thought that changes brought about by old age are not simple enough to be evaluated by question and answer [36].

The GUSS test is a bedside screening test developed by Trapl et al. [22], which can evaluate the oropharyngeal phase of swallowing and particularly determine the necessity for further evaluation in acute stroke patients and make neces-sary dietary modifications according to the results of this evaluation, as well as to minimize the risk of aspiration dur-ing all these evaluation processes.

In addition, the GUSS test has been accepted as a refer-ence and high-quality screening test which has led to the development of new screening tools [37]. The most impor-tant feature of GUSS is that it can evaluate swallowing with different kinds and volumes of liquid, semisolid and solid food that feature in everyday meals. This assessment

not only considers the pathophysiology of voluntary swal-lowing, but also allows patients to continue their oral feed-ing routine dependfeed-ing on the consistency. Therefore, we used the GUSS test in this study.

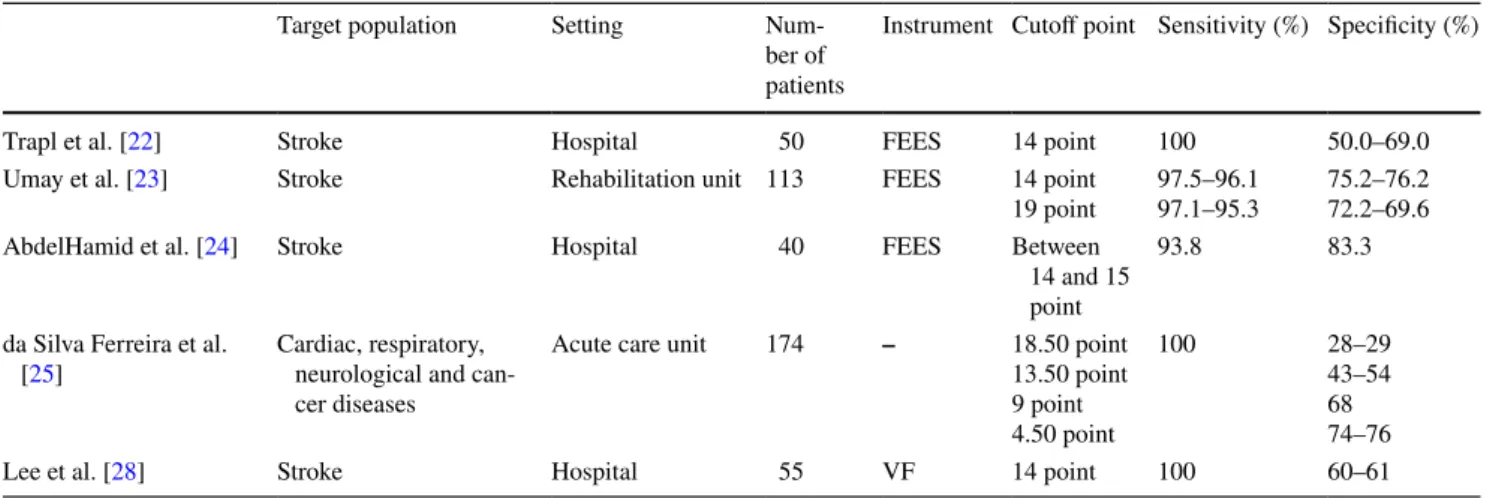

The validity and reliability of the GUSS test has been studied in 15 different countries in patients with neurologi-cal and non-neurologineurologi-cal dysphagia, of whom most were stroke patients. The inter-rater reliability was very good in these studies as it was in our own [22, 23, 25, 27, 28]. In addition, the validity of the test was evaluated in these studies by FEES and VF in terms of aspiration risk (cut-off point 14). We also used FEES for validity. It had high rates of diagnostic sensitivity (93.3–100%) and specificity (43.0–83.3%) in dysphagic patients (Table 6) [22–28]. In our study, even with a cutoff point of 18.50, the test had a sensitivity of 95.5% and a specificity of 94.4%. Moreover, the test had a sensitivity of 100% and had a specificity of 98% with a cutoff point of 14.5 which is indicative of aspiration risk.

Compared to studies with stroke patients, this study showed similar sensitivity but better specificity levels for aspiration. The difference between results can be explained by an underlying severe neurological condition causing care related or cognitive problems in stroke studies. In the present study, the factors that could cause secondary dysphagia were identified as exclusion criteria. For this reason, the GUSS test may be defined as a good screening test for independ-ent living in community older people without secondary dysphagia.

In addition, we used quality of life measurements for divergent validity. The GUSS test was moderately corre-lated with the quality of life, including its relationship with daily activities. Since eating and feeding is a social activity, dysphagia may provoke social dysfunction and energy loss due to a lack of motivation and feelings of unwillingness and embarrassment. In the literature, and similar to our study,

Table 6 The sensitivity and specificity results of the GUSS test in the literature

FEES flexible fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation, VF videofluoroscopy

Target population Setting Num-ber of patients

Instrument Cutoff point Sensitivity (%) Specificity (%)

Trapl et al. [22] Stroke Hospital 50 FEES 14 point 100 50.0–69.0

Umay et al. [23] Stroke Rehabilitation unit 113 FEES 14 point

19 point 97.5–96.197.1–95.3 75.2–76.272.2–69.6 AbdelHamid et al. [24] Stroke Hospital 40 FEES Between

14 and 15 point

93.8 83.3

da Silva Ferreira et al.

[25] Cardiac, respiratory, neurological and can-cer diseases

Acute care unit 174 – 18.50 point 13.50 point 9 point 4.50 point 100 28–29 43–54 68 74–76

there is a clear relationship between quality of life and dys-phagia [38].

The strength of this study is that it is multi-centered and large-scale. However, the limitation is that FEES was per-formed only in one center and other centers would not use endoscopy at all. Therefore, validation was performed with the results of one center.

Conclusions

This is the first study recommending the need for a test which can be used among healthy older individuals to pro-vide detailed psychometric evaluation. The GUSS is a valid and reliable test to identify possible OD risk in healthy older people, who have no secondary dysphagia. Even the 18.5 cutoff point has high sensitivity (95.5%) and speci-ficity (94.4%). In clinical practice, the GUSS test is per-fectly suited for older people with living independently in community.

Funding There is no funding source in this study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest There is no conflict of interest among the authors.

Ethical approval All the procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee ((Ethics committee of University of Health Sciences, Ankara Diskapi Training and Research Hospital) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or com-parable ethical standards.

Informed consent All participants or the relatives of illiterate par-ticipants were informed about the study and their written informed consents were obtained at the beginning of the study.

References

1. Cabre M, Serra-Prat M, Palomera E, Almirall J, Pallares R, Clave P (2010) Prevalence and prognostic implications of dysphagia in older patients with pneumonia. Age Ageing 39(1):39–45 2. Serra-Prat M, Hinojosa G, Lopez D, Juan M, Fabré E, Voss DS,

Calvo M, Marta V, Ribó L, Palomera E, Arreola V, Clavé P (2011) Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia and impaired safety and efficacy of swallow in independently living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 59(1):186–187

3. Yang EJ, Kim MH, Lim JY, Paik NJ (2013) Oropharyngeal dysphagia in a community-based older cohort: the Korean longitudinal study on health and aging. J Korean Med Sci 28(10):1534–1539

4. Holland G, Jayasekera V, Pendleton N, Horan M, Jones M, Hamdy S (2011) Prevalence and symptom profiling of oropharyngeal

dysphagia in a community dwelling of an older population: a self-reporting questionnaire survey. Dis Esophagus 24(7):476–480 5. Westmark S, Melgaard D, Rethmeier LO, Ehlers LH (2018) The

cost of dysphagia in geriatric patients. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 10:321–326

6. Wakabayashi H (2014) Presbyphagia and sarcopenic dysphagia: association between aging, sarcopenia, and deglutition disorders. J Frailty Aging 3:97–103

7. Ebihara S, Sekiya H, Miyagi M, Ebihara T, Okazaki T (2016) Dysphagia, dystussia, and aspiration pneumonia in older people. J Thorac Dis 8(3):632–639

8. de Lima Alvarenga EH, Dall’Oglio GP, Murano EZ, Abrahão M (2018) Continuum theory: presbyphagia to dysphagia? Functional assessment of swallowing in the older. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 275(2):443–449

9. Wirth R, Lueg G, Dziewas R (2018) Orophagyngeal dysphagia in older persons—evaluation and therapeutic options. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 143(3):148–151

10. Roy N, Stemple J, Merrill RM, Thomas L (2007) Dysphagia in the older: preliminary evidence of prevalence, risk factors, and soci-oemotional effects. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 116(11):858–865 11. Kawashima K, Motohashi Y, Fujishima I (2004) Prevalence of

dysphagia among community-dwelling older individuals as esti-mated using a questionnaire for dysphagia screening. Dysphagia 19(4):266–271

12. Almirall J, Rofes L, Serra-Prat M, Icart R, Palomera E, Arre-ola V, Clavé P (2013) Oropharyngeal dysphagia is a risk factor for community-acquired pneumonia in the older. Eur Respir J 41(4):923–928

13. Nogueira D, Reis E (2013) Swallowing disorders in nursing home residents: how can the problem be explained? Clin Interv Aging 8:221–227

14. Sarabia-Cobo CM, Pérez V, de Lorena P, Domínguez E, Her-mosilla C, Nuñez MJ, Vigueiro M, Rodríguez L (2016) The inci-dence and prognostic implications of dysphagia in older patients institutionalized: A multicenter study in Spain. Appl Nurs Res 30:e6–e9

15. Lancaster J (2015) Dysphagia: its nature, assessment and manage-ment. Br J Community Nurs 6a:S28–S32

16. Baijens LW, Clavé P, Cras P, Ekberg O, Forster A, Kolb GF, Leners JC, Masiero S, Mateos-Nozal J, Ortega O, Smithard DG, Speyer R, Walshe M (2016) European Society for Swallowing Disorders —European Union Geriatric Medicine Society white paper: oropharyngeal dysphagia as a geriatric syndrome. Clin Interv Aging 7(11):1403–1428

17. Khan A, Carmona R, Traube M (2014) Dysphagia in the older. Clin Geriatr Med 30(1):43–53

18. Jørgensen LW, Søndergaard K, Melgaard D, Warming S (2017) Interrater reliability of the Volume-Viscosity Swallow Test; screening for dysphagia among hospitalized older medical patients. Clin Nutr ESPEN 22:85–91

19. Rech RS, Hugo FN, Baumgarten A, Dos Santos KW, de Goulart BNG, Hilgert JB (2018) Development of a simplified dysphagia assessment by dentists in older persons. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 46(3):218–224

20. Clavé P, Arreola V, Romea M, Medina L, Palomera E, Serra-Prat M (2008) Accuracy of the volume-viscosity swallow test for clinical screening of oropharyngeal dysphagia and aspiration. Clin Nutr 27(6):806–815

21. Umay E, Eyigor S, Karahan AY et al (2019) Which swallowing difficulty of food consistency is best predictor for oropharyngeal dysphagia risk in older person. EGM 10(4):609–617

22. Trapl M, Enderle P, Nowotny M, Teuschl Y, Matz K, Dachen-hausen A, Brainin M (2007) Dysphagia bedside screening for acute-stroke patients: the Gugging Swallowing Screen. Stroke 38(11):2948–2952

23. Umay EK, Gurcay E, Bahceci K, Ozturk E, Yilmaz V, Gundogdu I, Ceylan T, Eren Y, Cakcı A (2018) Validity and reliability of Turkish version of the Gugging Swallowing Screen test in the early period of hemispheric stroke. Neurol Sci Neurophysiol 35:6–13

24. AbdelHamid A, Abo-Hasseba A (2017) Application of the GUSS test on adult Egyptian dysphagic patients. Egypt J Otolaryngol 33:103–110

25. da Silva Ferreira AM, Pierdevara L, Ventura IM, Gracias AMB, Marques JMF, dos Reis MGM (2018) The Gugging Swallowing Screen: a contribution to the cultural and linguistic validation for the Portuguese context. Rev Enf Ref 4(16):85–92

26. Lee KM, Kim HJ (2015) Practical assessment of dysphagia in stroke patients. Ann Rehabil Med 39(6):1018–1027

27. Xiao S, Chang H, Wu J, Shuai D, Ma J, Huang W, Liu J (2013) Chinese version of GUSS swallowing function assessment scale for reliability and validity. Chin J Mod Nurs 19(34):4189–4191 28. Lee KW, Kim SB, Lee JH, Kim MA, Kim BH, Lee GC (2009)

Clinical validity of Gugging Swallowing Screen for acute stroke patients. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med 33(4):458–462

29. Park YH, Bang HL, Han HR, Chang HK (2015) Dysphagia screening measures for use in nursing homes: a systematic review. J Korean Acad Nurs 45(1):1–13

30. Jiang JL, Fu SY, Wang WH, Ma YC (2016) Validity and reliability of swallowing screening tools used by nurses for dysphagia: a systematic review. Tzu Chi Med J 28(2):41–48

31. Dziewas R, Warnecke T, Olenberg S, Teismann I, Zimmermann J, Kramer C, Ritter M, Ringelstein EB, Schabitz WR (2008) Towards a basic endoscopic assessment of swallowing in acute

stroke-development and evaluation of a simple dysphagia score. Cerebrovasc Dis 26(1):41–47

32. Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH (2010) Psychometric theory. Tata McGraw-Hill Education, New York

33. Bowling A (2009) Research methods in health: Investigating health and health services. Open University Press, Buckingham 34. Molina L, Santos-Ruiz S, Clave P, lez-de Paz LG, Cabrera E

(2017) Nursing interventions in adult patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia: a systematic review. Eur Geriatr Med 9(1):5–21 35. Rofes L, Arreola V, Mukherjee R, Clave P (2014) Sensitivity and

specificity of the eating assessment tool and the volume-viscosity swallow test for clinical evaluation of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Neurogastr Motil 26(9):1256–1265

36. Uhm KE, Kim M, Lee YM, Kim BM, Kim YS, Choi J, Han SH, Kim HJ, Yoo KH, Lee J (2019) The Easy Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire (EDSQ): a new dysphagia screening questionnaire for the older adults. Eur Geriatr Med 10(1):47–52

37. Poorjavad M, Jalaie S (2014) Systemic review on highly qualified screening tests for swallowing disorders following stroke: validity and reliability issues. J Res Med Sci 19(8):776–785

38. Orlandoni P, Peladic NJ (2016) Health-related quality of life and functional health status questionnaires in oropharyngeal dyspha-gia. J Aging Res Clin Pract 5(1):31–37

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to