Traditional Child Care Practices Among Mothers With Infants Less

Than 1 Year Old

Ayşe Beşer, Sevcan Topçu, Ayşegül Çoşkun, Nilay Erdem, Rüveyda Gelişken, Derya Özer Abstract

Background: Mothers not equipped with sufficient knowledge about child care and using traditional child care methods may cause harm to their children’s health and even cause handicaps in their children. Objective: The aim of this study was to determine traditional child care practices of women with infant less than one years age babies. Methods: The descriptive study was conducted in the four districts of Izmir, where health care is offered by the Primary Health Center. Data were collected by face to face with a questionnaire prepared by the researchers in view of the relevant literature. The study sample included 70 mothers with infant less than one year old babies. Results: Turkish mothers had traditional child care practices pertinent to bathing and cutting nails of babies for the first time, swaddling, removal of the umbilical cord, the evil eye and “kırk basması”. Conclusion: Some of these traditional health behaviors can cause health risks. Therefore, nurses should be aware of traditional behaviors which may pose health risks and attempt to change these behaviors.

Key Words: Culture, Child Care, Traditional Practices, Nursing.

Bir Yaşından Küçük Bebeğe Sahip Annelerin Geleneksel Bakım Uygulamaları

Giriş: Çocuk bakımı konusunda yeterli bilgiye sahip olmayan ve geleneksel çocuk bakım yöntemlerini kullanan anneler çocuklarının sağlığına zarar verebilir ve hatta onlarda sakatlıklara yol açabilir. Amaç: Bu çalışmanın amacı bir yaşından küçük bebeğe sahip olan annelerin geleneksel çocuk bakımı uygulamalarının belirlenmesidir. Yöntem: Tanımlayıcı tipte planlanan bu çalışma birinci basamak sağlık hizmeti sunulan İzmir ilinde dört sağlık ocağı bölgesinde yürütülmüştür. Veriler literatüre dayanılarak araştırmacılar tarafından hazırlanan anket formu ile toplanmıştır. Çalışmanın örneklemini bir yaşından küçük bebeği olan 70 anne oluşturmuştur. Bulgular: Türk anneler bebeğin ilk tırnağını kesme, ilk banyosu, kundaklama, göbek bağının atılması, nazar ve kırk basması ile ilgili geleneksel çocuk bakımı uygulamalarına sahiptir. Sonuç: Bu geleneksel sağlık davranışlarından bazıları sağlık risklerine yol açabilir. Bu nedenle hemşireler sağlık risklerine yol açabilecek geleneksel uygulamaların farkında olmalı ve bu davranışları değiştirmeye çalışmalıdır.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Kültür, Çocuk Bakımı, Geleneksel Uygulamalar, Hemşirelik.

Doç. Dr., Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Hemşirelik Yüksekokulu, Halk Sağlığı Hemşireliği Anabilim Dalı, İnciraltı/ İzmir E-mail: ayse.beser@deu.edu.tr t present, insufficient pre-, peri- and post-natal care

causes maternal and child health problems in the world especially in developing countries. Of all deaths which occur in the first five years of life, 36% are neonatal deaths. In fact, of the approximately four million global neonatal deaths that occur annually, 98% occur in developing countries, predominately at home (Lawn et al., 2004). As most births and deaths occur out-side any established health care facility, a reduction in the neonatal mortality may depend significantly on inter-ventions involving promotion or adaptation of traditional care behaviors practiced at home. Feeding with colost-rums, timing of first breastfeeding and duration of bre-astfeeding, umbilical cord care, and measures taken to prevent hypothermia of newborns are important factors in health and survival during the neonatal period. Practi-ces just after the delivery and postpartum period also deserve attention (Mullany, Darmstad, Khatry & Tielsch, 2005).

Insufficient care before, during and after pregnancy still cause maternal and child health problems in Turkey as well. According to Demographics and Health Survey (DHS) made in Turkey in 2008, the infant death rate was 17‰ and 13‰ of the infantile deaths occurred in the neonatal period. Of all deaths which occur in the first years of life, 76% are neonatal deaths (DHS, 2008). Data from World Health Organization (WHO), The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) (2000) show that di-arrhea, pneumonia and bronchitis are the leading causes of death among infants. Several studies have revealed that several traditional neonatal care practices which va-ry with culture may cause infections, anemia, hypother-mia and hypoglycehypother-mia and thus increase the risk for diseases among infants (Marsh et al., 2002; Winch et al., 2005).

Cultural values, attitudes, beliefs and behaviors affect life style and health. Therefore, culture is considered a dynamic factor which plays an important role in health and diseases (Baltaş, 2000). Traditional practices resulting from values of a particular culture affect children most. A family, which mirrors values, traditions, customs and be-liefs, i.e. culture of a society to which it belongs, plays an important role in physical, psychological and social development and health in children (Toksöz, 1992; Reifs-nider, Allan, Percy, 2000). Traditional child care practices affect children’s health.

Although they may vary from culture to culture, preg-nancy, birth and child care related beliefs and practices appear in all communities and may play an important role in child health. Mothers not equipped with sufficient knowledge about child care and using traditional child care methods may cause harm to their children’s health and even cause handicaps in their children. Mothers’ attitudes towards health, health behaviors, education level and practices during illnesses of their children also play an important role in child health (Platin & Khorshid, 1994; Ofluoğlu & Saruhan, 1995). Therefore, nurses should be able to identify and analyze values likely to affect health behaviors.

Literatüre review

Definitions of health and disease vary with culture, causes, clinical courses and distributions of diseases are determi-ned by cultural elements and diseases are treated with practices which may change from culture to culture. Therefore, culture is considered as a dynamic determinant of health and diseases. Birth and child care related beliefs and practices are also regarded as cultural elements which affect health (Aksayan & Hayran, 1992). There are various traditional child care practices in different cultures.

In India, breastfeeding is believed to be good and God’s gift and cultural practices surround its initiation. According to Sushruta (ancient Indian scriptures), breast-feeding should begin on the 5th day, and sometimes breastfeeding is initiated on the 6th day after a celebration called chhatti. Honey is the most common first food, fol-lowed by sugar water. According to Sushruta, honey and ghee should be given to evacuate the meconium (Choudry, 1997). However, feeding babies with those culture specific foods immediately after birth are harmful to babies and should be discouraged.

Reissland and Burghart (1988) observed in their study that colostrum was thought to remain in the breasts for nine months, considered as “stale milk” and was not given to babies and that babies were first fed 4-12 hours after birth. They noted that babies first given honey or sugar water were supposed to have an enjoyable life. Fikree, Ali, Durocher and Rahbar (2005) and Winch et al. (2005) re-ported that babies were first fed with sugar water or traditional mixtures. Mattson (2000) found that Asian and Spanish women thought colostrum to be bad or dirty and therefore did not give it to their babies. Fikree et al. (2005) found that Pakistani women used such oils as mustard oil and coconut oil or several traditional mixtures such as ghee and surma for umbilical cord care. Winch et al. (2005) also reported that mothers covered umbilical cords of their babies with a hot mixture which contained mustard oil and garlic two times a day.

Winch et al. (2005) from Bangladesh reported that ba-bies were not taken out for nine days after birth and that charms with words from Koran are used to protect neo-nates and their mothers against jealous people and malevolent spirits thought to cause diseases. Zoysa, Bhandri, Akhtari and Bhan (1998) and Choudry (1997) from India found that charms given by religious leaders were used and that black dot of kujul (black soot mixed in butter) was placed on the newborn’s forehead to avoid the evil eye. In addition, they noted that articles made of iron were kept under the newborn’s bed to thwart the evil eye.

In Turkey, there are traditional practices concerning the first bath of babies, thrush, diaper rash, cutting nails, jaundice, removal of the umbilical cord, swaddling and “kırk basması” (Aksayan, 1982; Bahar & Bayık, 1985; Toksöz, 1992).

Traditional Child Care Practices in Turkey Time of the First Breastfeeding

Babies are not breastfed until the azan* is heard three times. It is attributed to the belief that babies would be patient when they grow up. Instead of breast milk, babies are given sugar water until their first breastfeeding (Tok-söz, 1992; Platin & Khorshid, 1994; Ofluoğlu & Saru-han, 1995). Özyazıcıoğlu and Polat (2004) noted that 84% of the mothers breastfed their babies soon after delivery, but that the rest did not breastfeed their babies until they heard three to five azans. Sahinöz et al. (2005) reported that of all infants aged 0-59 months, 1.9% was not fed after birth, 35% was fed in one hour after their birth, 31.9% were fed in 2-14 hours of their birth and 31.2% were fed 24 hours after their birth. They also noted that 56.4% and 35% of the infants were given breast milk and sugar water after birth respectively. Several other studies have revealed that mothers do not

* in Islamic countries the call in Arabic to prayer proclaimed five times a day by the muezzin.

feed their babies until they hear the azan a few times and give sugar water to their babies after birth (Ergenekon-Ozelci, Elmacı, Ertem & Saka, 2001; Biltekin, Boran, Denkli & Yalçınkaya, 2004)

According to the Demographics and Health Survey made in Turkey in 2008, 39% of the infants are breastfed within one hour of birth and 73.4% are breastfed within 24 hours of birth. These data indicate that breastfeeding starts quite late after birth in Turkey. In our country, mothers believe that breast milk is not sufficient and they have ma-ny traditional practices concerning breastfeeding. For these reasons, infant nutritional status is poor, which predisposes to infections and has a negative impact on infant growth and development.

Swaddling

In many parts of Turkey, mothers swaddle their babies tightly in order to keep them warm or in order that babies can be strong, have beautiful legs or just sleep well (Ba-har & Bayık, 1985; Platin & Khorshid, 1994; Özyazı-cıoğlu & Polat, 2004). Gözüm (1992) reported that 75.8% of the mothers swaddled their babies and that most of these mothers were middle aged. Biltekin et al. (2004) found that 74% of the mothers swaddled their babies so that their legs should be beautiful. In rural areas, it is still believed that swaddling keeps babies warm. Dinç (2005) found out that 74% of the mothers in Turkey swaddled their babies and that 62.8% did not know why they did it. Of the mothers who knew why they swaddled their babies, 24.3% did it so that babies should have beautiful arms and legs and 12.8% did it so that their babies did not fall off while asleep. In a study by Eğri and Gölbaşı (2007), 89.8% of the mothers turned out to swaddle their babies so that they slept well and had beautiful legs and their backs should be comfortable. Swaddling is quite common in Turkey. Babies whose arms and legs are tied do not feel comfortable, cry and are restless. In fact, it prevents babies from moving their arms and legs freely. In addition, it may induce hip dislocation in babies with a congenital predisposition to the disorder. For these reasons, swaddling can be considered harmful to infant health.

The first bath of babies

Yalın (1998) found that babies were bathed on the seven-th or ninseven-th day of seven-their birseven-ths. In addition, baseven-thwater is added gold, silver, hellebore, forty grains of rice, etc. so that babies or their mouths do not smell bad in their later lives (Özden, 1987; Platin & Khorshid, 1994).A small amount of salt is also added to bathwater and then babies are rinsed (Balıkçı, 2005; Platin & Khorshid, 1994). Biltekin et al. (2004) revealed in their studies that mot-hers applied salt on their infants’ skin so that infants should not smell bad. Dinç (2005) reported that 39% of the mothers applied salt on their babies and added that 32.5% of the mothers applied salt so that their babies should not smell bad and that 23.4% did it so that ery-thema should decrease and diaper rash should be prevented. Eğri and Gölbaşı (2007) also noted that 64% of the mothers applied salt to avoid bad smell in the future and to prevent diaper rash. In addition, Mothers applies salt to prevent sweating. However sweating is necessary for body.

Cutting nails

Cutting nails until the age of one year is not acceptable. It is believed that babies whose nails are cut before the

age of one year would be thieves. It is also believed that angels cut babies’ nails and that cutting their nails is a sin (Balıkçı, 2005; Özkan & Khorshid, 1995). Sezen noted that children’s nails were not cut until their first teeth erupted or even until they could pick up a change from their fathers’ pockets. Mothers believed that children would be healthy and earn a lot in the future if their nails were not cut earlier (Sezen, 1994).

Jaundice

Jaundice is a common symptom in newborn babies and, in most instances, is relatively benign. However some-times, it can indicate a pathological state. In Turkey, newborn babies are covered in a yellow cloth as it is thought to prevent jaundice (Özyazıcıoğlu & Polat, 20-04). During the neonatal period, mothers give their babies sugar water, cover them with a yellow fabric or do not give the colostrum to their babies in order to protect them against jaundice. It is believed that yellow fabrics used to cover babies for the first four days of life prevent or cure jaundice (Bayat, 1987; Özkan & Khors-hid, 1995). Biltekin et al. (2004) reported that 35% of the mothers washed their babies with papaver (redcap) juice, covered them with a yellow fabric or cut the skin bet-ween the two eyebrows with a razor blade to relieve jaundice. Dinç (2005) found that 25.7% of the infants had jaundice and that 47.3% of those infants were taken to religious leaders who made a cut behind their ears and instilled the resultant blood into babies’ eyes. Eğri and Gölbaşı (2007) found that 73.6% of the mothers covered their babies’ face with a yellow cloth and that 20% washed their babies with a mixture of one unit nitric acid and three units of hydrochloric acid to prevent jaundice.

Removal of the umbilical cord

There is a belief in some regions that children may not be dedicated to their families if their umbilical cords are thrown out. Some people bury their babies’ umbilical cords in front of a mosque so that their babies are pious or leave in the backyard of a school so that their babies have a good education (Aksayan, 1982; Bahar & Bayık, 1985; Özkan & Khorshid, 1995; Özyazıcıoğlu & Polat, 2004). According to a study by Eğri and Gölbaşı (2007), 48.2% of the mothers kept the umbilical cord at home, 18.2% kept it somewhere nobody steps, 14.2% buried it in the school yard, 8.9% buried it in the garden and 8.1% buried it in the mosque.

The evil eye

It is believed that the evil eye results from jealousy and it is a magical power used to cast a spell on someone by looking at them so that bad things happen to them. The evil eye is believed to affect babies most because they are thought to be weak. Therefore, blue beads, a written charm or a piece of garlic are attached to babies’ clothes to avert the evil eye (Balıkçı, 2005). In a study by Dinç (2005), 72% of the mothers believed in the evil eye and 38.8% of those mothers who believed in the evil eye prayed and 18.4% sprinkled lead, salt or sugar on babies to avoid the evil eye. Eğri and Gölbaşı (2007) revealed that 93.3% of the mothers believed in the evil eye and prayed, wore blue beads and had religious leaders pray or make charms. Aksayan and Hayran (1992) mentioned

another traditional practice called “kurşun dökme”*** in Turkish, which is used to relieve effects of the evil eye.

Kırk basması

Diseases which lactating women and babies suffer from within forty days of birth are traditionally called “kırk basması”, “kırk karışması” or “loğusa basması” in Tur-kish. It is widely believed that some living or nonliving things harm lactating women and forty-day-old babies (Aksayan, 1982; Bahar & Bayık, 1985; Özkan & Khorshid, 1995).In order to avoid “kırk basması”, lacta-ting women hug each other when they come across, pets like cats and dogs are not allowed in lactating women’s rooms and Koran, needles, a piece of bread, a broom or instruments made of iron are left near babies to help them avoid contracting the diseases during lactation (Aksayan, 1982; Bahar & Bayık, 1985; Balıkçı, 2005; Aksayan & Hayran, 1992).

In addition, there are other traditional practices in Turkey. For example, powder, olive oil and coffee are applied on the umbilical cord and soil is put under babies to remove the cord easily (Geçkil, Şahin & Ege, 2009).

There is no large-scale study which reveals all traditio-nal child care practices performed on women with infants younger than one year old in Turkey. Therefore, we carried out the present study to address this gap in knowledge, ga-in an understandga-ing of traditional practices and ga-investigate the factors influencing such practices. To this aim, we searched for the answers to the following questions in this study:

What traditional child care practices were performed by mothers with infants younger than one year old?

Was there a relation between traditional child care practices and mothers’ income, family type, education, origin and residence?

Method

Research type

This is a descriptive study.

Where research is carried out

This research was conducted in four districts of İzmir, located in the western part of Turkey. In those districts, health care was offered in Primary Health Centers. Three districts had urban characteristics and two of them had higher socio-economic status. One district with urban characteristics had a high rate of unemployment and low income. Immigration from the eastern part of Turkey to that district was still continuing. The remaining two districts with urban characteristics had a population with regular income working in government institutions. The number of people migrating from the eastern part of Turkey was evenly distributed in three districts of the city with urban characteristics. One district had rural characteristic, was located outside the city and had higher socio-economic status. The residents of the district were working in agriculture (growing olives and citrus fruit etc.) and had a high income.

*** Kurşun dökme: A piece of lead is melted over heat and the melted lead is poured into water. When exposed to water, it forms various patterns. The person who performs this procedure makes predictions about a given person based on the patterns. The procedure is believed to protect against evil spirits.

Sample

The families included in the study were selected based on the records in primary health care centers. The women with babies less than one year old were eligible. Nursing students detected health problems of families and conducted appropriate nursing interventions. They visited families once a week for three months. The study sample included 70 women with infants less than one year old and who accepted to participate in the study. Data were collected from volunteering women from the families followed by third year nursing students during their public health nursing practice. During a public health nursing practice, the 70 mothers with babies less than one year old were followed. All of 70 mothers agreed to participate in research. All mothers who were living near Primary Health Centers in the study area, who had infants younger than one year old, who could speak Turkish and who had no communication problems were included in the study.

Instruments

Data were collected with a questionnaire developed by the researchers. The questionnaire was composed of for-ty-two multiple choice and open-ended questions. The mothers were asked whether traditional practices was made their infants about first bath, cutting nails, jaundice, removal of the umbilical cord, swaddling, evil eye, kırk basması and breastfeeding. The mothers, who answered “yes”, were asked to explain these practices. Nursing students who interviewed mothers were offered training for interviews. Data were collected at face to face interviews which lasted for 20-25 minutes.The questionnaire used to collect data was composed of 42 questions about demographic characteristics and traditio-nal child care practices. There were a total of 12 ques-tions about demographic characteristics such as age, education, employment, income, origin and family type. There were a total of 30 questions about traditional child care practices about the time of first breastfeeding, the way of first bathing, the time of the first nail cut and jaundice, the evil eye and “kırk basması”.

Analyses of data

Data were evaluated with SPSS for WINDOWS version 10 and analyzed with Chi-square test and percentages. Answers to open-ended questions about traditional child care practices were listed and changed into percentages. Chi-square test was used to determine the relation bet-ween obtained percentile data and independent variables (family type, education, income, residence and origin).

Ethical considerations

Approval was obtained from the ethical committee of Dokuz Eylül University of Nursing School. The mothers included into the study gave informed consent. They were assured that the obtained data would be confiden-tial.

Findings

The study sample included 70 mothers with infants younger than one year old visited by the third grade nursing students of Dokuz Eylul University during their public health nursing practice. The mean age of the mothers was 27.08 ± 4.42 years. Ninety-four point three percent of the mothers were literate, 55.1% were high school or university graduates and 20% employed. Eleven point four percent was from the Middle Anatolia

and 4.3% from the Mediterranean Region. Sixty-one point four percent of the mothers noted that their incomes were equal to their expenses. Fifteen point seven percent had a nuclear family.

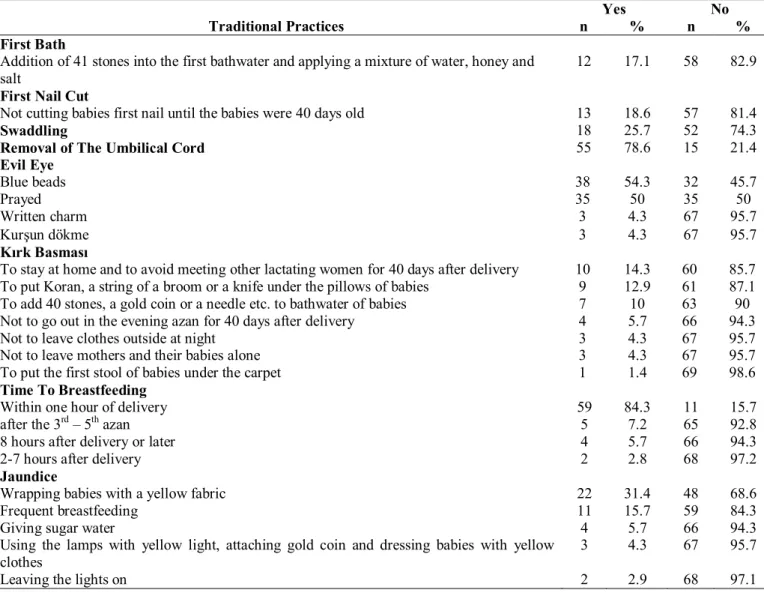

Of all mothers, 17.1% used traditional practices such as addition of 41 stones into the first bathwater and applying a mixture of water, honey and salt to the lips, armpits and genitals of their babies and rinsing these body parts after a while. They believed that their babies would smell good, have the ability to speak well and become rich in their later lives (Table 1). There was no significant difference between traditional practices of bathing and income, family type and origin (p > .05).

Eighteen point six percent of the mothers did not cut their babies’ first nails until the babies were 40 days old. Time to cut the first nails of babies varied between 40 days and fourmonths after delivery. In addition, they put their babies’ hands into their husbands’ pockets or put their babies’ cut nails in their husbands’ wallets. They expected that their babies would be rich and would not become thieves. In addition, mothers did not cut nails at night in case it brought bad luck. There was no signi-ficant difference between practices of cutting nails and residence, income, family type, education and origin (p > .05).

Twenty-five point seven percent of the mothers s-waddled their babies (Table 1). There was no significant difference between swaddling and residence, family ty-pe, education and origin (p > .05).

Seventy-eight point six percent of the mothers kept their babies’ umbilical cords at home so that the babies were loyal to their families; they buried the cords at a school yard or on a campus so that the babies had a good education or left the cords in a mosque so that the babies were devoted to God. There was no significant differen-ce between umbilical cord related practidifferen-ces and residen-ce, income, family type, education and origin (p > .05).

Eighty-two point nine percent of the mothers had tra-ditional practices to protect their babies against the evil eye (Table 1). To avert the evil eye, 54.3% of the mot-hers used blue beads, 50% prayed, 4.3% used a written charm, 4.3% performed the superstitious custom of mel-ting lead and pouring it into cold water and moving over the head of a stick person (kurşun dökme) and 6.7% picked up threads from the clothes of people who stroked their babies, washed their babies’ faces with water from the toilet tap, put some salt on fire and moved it over the babies while praying and heated a special grass and moved its smoke over the babies. There was no signifi-cant difference between traditional practices relevant to the evil eye and residence, income, education and origin (p > .05).

Forty percent of the mothers believed in “kırk bas-ması” and had traditional practices to prevent it (Table 1). Fourteen point three percent of the mothers did not take their babies out and avoided meeting other lactating women for forty days after delivery and 12.9 % put such objects as Koran and a string of a broom under the pillows of their babies (Table 1). There was no signifi-cant difference between the belief in “kırk basması” and income, family type, education and origin (p > .05).

Of all mothers included in the study, 84.3% breastfed their babies within the first hour of delivery and 7.2% did not breastfeed their babies until they heard the azan three-five times and gave sugar water to their

Table 1. Traditional Child Care Practices

Yes No

Traditional Practices n % n %

First Bath

Addition of 41 stones into the first bathwater and applying a mixture of water, honey and salt

12 17.1 58 82.9

First Nail Cut

Not cutting babies first nail until the babies were 40 days old 13 18.6 57 81.4

Swaddling 18 25.7 52 74.3

Removal of The Umbilical Cord 55 78.6 15 21.4

Evil Eye Blue beads 38 54.3 32 45.7 Prayed 35 50 35 50 Written charm 3 4.3 67 95.7 Kurşun dökme 3 4.3 67 95.7 Kırk Basması

To stay at home and to avoid meeting other lactating women for 40 days after delivery 10 14.3 60 85.7

To put Koran, a string of a broom or a knife under the pillows of babies 9 12.9 61 87.1

To add 40 stones, a gold coin or a needle etc. to bathwater of babies 7 10 63 90

Not to go out in the evening azan for 40 days after delivery 4 5.7 66 94.3

Not to leave clothes outside at night 3 4.3 67 95.7

Not to leave mothers and their babies alone 3 4.3 67 95.7

To put the first stool of babies under the carpet 1 1.4 69 98.6

Time To Breastfeeding

Within one hour of delivery 59 84.3 11 15.7

after the 3rd – 5th azan 5 7.2 65 92.8

8 hours after delivery or later 4 5.7 66 94.3

2-7 hours after delivery 2 2.8 68 97.2

Jaundice

Wrapping babies with a yellow fabric 22 31.4 48 68.6

Frequent breastfeeding 11 15.7 59 84.3

Giving sugar water 4 5.7 66 94.3

Using the lamps with yellow light, attaching gold coin and dressing babies with yellow clothes

3 4.3 67 95.7

Leaving the lights on 2 2.9 68 97.1

babies instead of breast milk. In addition, the first breast-feeding was accompanied by a religious leader (Table 1). There was no significant difference between breast-feeding related practices and residence, income, family type, education and origin (p > .05).

Sixty percent of the mothers practiced some traditions to protect their babies against jaundice (Table 1). Thirty-one point four percent covered their babies with a yellow fabric, 2.9% left the lights on and 5.7% gave their babies sugar water (Table 1). There was no significant difference between education, income, origin, residence and family type and traditional practices (p > .05). Of all the women who performed traditional child care practices, 18.6% were influenced by their parents and 5.7% were influenced by others.

Discussion

In Anatolian culture, the postpartum period is counted as a period when mothers and their babies are more vul-nerable to illnesses. The mothers maintain to follow a number of traditional practices in order to protect those illnesses (Geçkil et al., 2009). According to the study out-comes these traditional practices are still perceived as important in the postpartum period in Turkey. We found that Turkish mothers had traditional child care practices concerning first bathing, first nail cut, breast-feeding, jaundice and removal of the umbilical cord, swaddling, the evil eye and “kırk basması” (Table 1). Culture, including traditions and customs, affects

indi-viduals. Indeed, an individual is under the influence of culture from birth to death (Aksayan, 1982; Baltaş, 2000; Taşdemir, Hayran, Akgöz & Çalı, 1994). Some of these practices may not have any harmful effects on health, while others do so. Therefore, it is required that traditio-nal health care practices should be investigated and those which are useful should be preserved, but that harmful ones should replaced by useful ones (Taşdemir et al., 1994). Nurses should also be aware of harmful traditio-nal health care practices of individuals they provide care for and attempt to change them.

Neonates are quite susceptible to diseases and if symptoms of diseases are not evaluated carefully, diseas-es may show a rapid progrdiseas-ess and cause untoward effects such as handicaps and even death. For these reasons, appropriate care for neonates should include good nutri-tion, special care for the umbilical cord, hygiene, measu-rement of body temperature and follow-up of disease symptoms in both mothers and babies (Marsh et al., 2002).

The results of this study confirmed that the mothers included in the study performed traditional child care p-ractices concerning the first bath of babies. Studies from different cultures have revealed such traditional child care practices as bathing babies just after birth or after massaging them with various mixtures likely to harm the skin of neonates (Fikree et al., 2005; Winch et al., 2005). Studies from different regions of Turkey have revealed

similar traditional child care practices. Biltekin et al. (2004) and Dinç (2005) from Turkey have noted that most of the mothers applied salt to the skin of babies so that they did not smell bad. The results of the present study were consistent with those of the study by Ofluoğlu and Saruhan (Ofluoğlu & Saruhan, 1995). The mothers believe that their babies do not smell bad, but speak well and become rich when they practice the traditions relevant to the bath of their babies. However, such practices may give harm to the skin of babies or may cause hypothermia, one of the most important factors which increase the risk of infections in the neonatal period. Therefore, nurses should inform mot-hers about the damage caused by traditional practices concerning the first bath of babies. The present study s-howed not only harmful practices but also such practices with no harmful effects as adding 41 stones or honey into bathwater.

The results of the present study showed that the mothers did not have traditional practices concerning the first nail cut likely to affect health of neonates, but had various behavioral patterns related to the first nail cut. Mothers were found to put their babies’ hands into their fathers’ pockets or put the nails into the babies’ fathers’ wallets so that the babies should not become thieves but earn a lot of money. In addition, they did not cut the nails at night in case it brought bad luck. However this application is not harmful. It may help to prevent injuries to infants due to lack of light. These behavioral patterns were also mentioned by Sezen from Turkey. However, Balıkçı et al. observed different behavioral patterns concerning the first nail cut (Balıkçı, 2005; Özkan & Khorshid, 1995). To our knowledge, there have not been any studies from other cultures reporting traditional practices concerning the first nail cut. The above mentioned traditional practices related to the first nail cut can only be encountered in Turkey. The present study demonstrated that the mothers swaddled their babies. Swaddling is a popular traditional practice performed by Turkish mothers (Dinç, 2005; Biltekin et al., 2004; Geçkil et al., 2009). In fact, in a study by Dinç (2005), most of the mothers were found to swaddle their babies. Biltekin et al. (2004) reported that 74% of the mothers swaddled their babies so that babies should have beautiful legs. Geçkil et al. (2009) reported that 86.8% of the mothers tightly swaddled their baby’s limbs for aesthetic reasons. As far as we know, there have not been any studies showing that mothers from other cultures swaddle their babies (Fikree et al., 2005; Mattson, 2000; Winch et al., 2005; Zoysa et al., 1998). Turkish women either wrapped the whole body of their babies or only the waist and legs. The women preferred swaddling just because their parents did so or they believed that swaddling provided comfort and warmth for the babies, alignment of their extremities and joints and allowed them to hold their babies easily. Swaddling has been used for ages and is still common, which indicates the power of values and traditional practices transferred from one generation to another. Swaddling does not affect growth and development of babies when it is loose and when it covers only the body parts below the waist. However, when it is tight, it prevents body movements and may cause health risks. In fact, it is one of the leading causes of congenital hip dislocation. Therefore, nurses should discourage mothers from swaddling their

babies and inform them about negative effects of swaddling such as hip dislocation and restlessness.

In this study, traditional practices related to the um-bilical cord were found to be the most frequent practices with no negative effects on infant health. The mothers often kept the umbilical cord at home so that their babies should be devoted to home, they buried it so that the babies should earn a lot in their later lives, they buried it at a school garden or on a campus so that their babies should have good education and they buried it in the garden of a mosque so that their babies should be devo-ted to God. Umbilical cord reladevo-ted traditional practices are very similar in different regions of Turkey. In fact, mothers have the same expectations from those practices (Aksayan, 1982; Bahar & Bayık, 1985; Özyazıcıoğlu & Polat, 2004; Özkan & Khorshid, 1995). Geçkil et al. (2009) reported that 77.1% of the mothers would keep the umbilical cord in a special place and, later would throw it into a river or bury the cord in the mosque or school. It is believed that the personality of a baby is influenced by the place where umbilical cord is buried.

There have been studies from other cultures reporting different negative traditional practices related to the um-bilical cord. Fikree et al. (2005) and Winch et al. (2005) reported that mothers applied garlic, mustard oil, coconut oil and ghee for umbilical cord care, which put infants’ health at risk and increases the risk of infections.

The evil eye is called “nazar”, “göz değmesi”, “göze gelme” or “kötü göz” in Turkish and it is believed to be caused by jealousy, covetousness and other negative feelings (Balıkçı, 2005). Most of the mothers included in this study had traditional practices to avert the evil eye. Many studies from Turkey and other countries have revealed that mothers believed in the evil eye and performed some traditional practices to avoid it. Özyazı-cıoğlu and Polat (2004) noted that 70% of the mothers believed in the evil eye and therefore wore a written c-harm or blue beads or asked a religious leader to pray for their babies. Aksayan and Hayran (1992) found that mot-hers performed “kurşun dökme” when they thought that their babies were exposed to the evil eye.

Zoysa et al. (1998) and Choudry (1997) found that an unpleasant or a jealous look caused the evil eye and that mothers applied kujul on the foreheads of their babies or used written charms given by the religious leaders to avert the evil eye. Winch et al. (2005) from Bangladesh reported that babies were not taken out for nine days after birth and that charms with words from Koran were used to protect neonates and their mothers against jealous people and malevolent spirits supposed to cause diseases.

The results of the present study are consistent with the literature. A large number of traditional practices are still used to heal babies affected by the evil eye in some societies. Some people are believed to have the evil eye. In fact, it is thought that people with the evil eye cause disease, disabilities and death in a human or an animal only when they stare at them (Balıkçı, 2005). Most of the traditional practices used by the mothers to heal affected babies are harmless. However, the signs of fever, rest-lessness and cyanosis may indicate presence of a disease and babies with these signs should be taken to hospital. For this reason, public nurses should offer information to mothers about signs of diseases and urge them to take their babies to hospital in case of a disease.

We found that the mothers believed in “kırk bas-ması”. Those mothers had some traditional practices to protect their babies against “kırk basması”. The mothers did not take their babies out and avoided meeting other lactating women for forty days after birth and mothers put Koran, a string of a broom etc. under the pillows of their babies (Table 1). Actually, diseases lactating wo-men and their babies suffer from within forty days of birth and growth retardation which may occur later are called “kırk basması” in Turkish (Balıkçı, 2005). It is commonly believed that some living and nonliving things may give harm to lactating women and their babi-es. In a study by Bahar and Bayık (1985), 18.1% of the subjects did not believe in “kırk basması”, 29.8% had no idea about it, 36.6% noted that “kırk basması was a disease. Choudry (1997) and Winch et al. (2005) revea-led the belief that mothers and their babies were vulnerable to diseases and evil spirits and therefore they should not go out for a period of time after birth. It pro-vides protection for mothers and babies from the disease but today is not suitable for. During a time of the unknown causes of diseases, the ships which carried patient were quarantined in harbor for 40 days. Now-adays, this application may be reflected like that mothers and their babies should not go out for a period of time after birth. It is required that signs of diseases should be followed carefully and neonates with signs of diseases should be taken to hospital so that they receive approp-riate neonatal care. Mothers’ belief in the evil eye and “kırk basması” should be considered as risk factors for neonatal health and therefore, nurses should be alert to negative effects of these beliefs on neonates’ health.

In the present study, most of the mothers breastfed their babies within one hour of delivery, but 7.2% did not do it until they heard the azan three-five times (Table 1). Ergenekon-Ozelci et al. from Turkey (2001) reported that 68.8% of the mothers started breastfeeding two days after birth and that 73.4% of the mothers gave sugar water as the first food. They concluded that culture and beliefs had a significant impact on breastfeeding and could be harmful to neonates. A study by Savaş, Alpaslan and Ağrıdağ from Turkey (1994) revealed that 63% of the mothers breastfed their babies soon after birth and that 32.5% gave their babies sugar water.

Geçkil et al. (2009) noted that nearly half of the women (45.4%) fed their babies with water containing sugar, 11.7% fed their babies with a mixture of butter and honey, 9.9% waited for three azan calls before commencing their first breastfeeding, and 11% mothers fed their babies just after birth. According to a study by Bohler, Semega, Holm and Matheson (2001), 60.9% of the mothers started breast-feeding soon after birth and 20.7% breastfed their babies on the second day of their birth. Fikree et al. (2005) and Winch et al. (2005) found that babies were first fed with sugar water or traditional mixtures and Mattson (2000) found that Asian and Spanish women did not give colostrums since they considered it dirty or bad. According to a report from WHO/UNICEF in 2000, the leading diseases which cause neonatal deaths in developing countries are infectious diseases such as diarrhea, pneu-monia and bronchitis and one of the most practical preventive measures against these diseases is breastfeeding (WHO/UNICEF, 2000). The results of this study and other studies from Turkey showed that the rate of women who started breastfeeding within the first hour of birth was

quite high and that the rate of women who performed traditional practices concerning breastfeeding was low. Breastfeeding just after delivery is important in that babies acquire the suckling reflex and that breastfeeding helps mother-baby bonding and quickens milk production (Alp, Yaman & Altınkaynak, 1993). Breastfeeding within one hour of birth is desirable. This study revealed that nurses and midwives took an active role in early breastfeeding.

The mothers included in this study were found to w-rap their babies with a yellow fabric, leave the lights on and give their babies sugar water (Table 1). They believ-ed that the color yellow would (somehow) avoid jaun-dice. Consistent with the results of the present study, Geçkil et al. (2009) reported that 89% of the mothers placed a yellow cloth over their babies to protect them against jaundice. It is believed that the baby will not have jaundice if it has been covered with a yellow cloth for 40 days. In addition, the abovementioned study re-vealed that one-third of mothers had taken their babies to a Muslim preacher and that a quarter had cut their babi-es’ nose, backs of ears, backs or limbs in order to cure jaundice. Biltekin et al. (2004) found that 35% of the mothers washed their babies with papaver (redcap) juice, covered them with a yellow fabric or cut the skin bet-ween the two eyebrows with a razor blade to relieve jaundice. Dinç (2005) also noted that most of the mothers asked a religious leader to incise their babies’ ears with a razor blade when the babies had jaundice. To our knowledge, there have not been any studies from other cultures showing traditional practices concerning jaundice. Encouraged by midwives and doctors, the breastfeeding mothers noted that they breastfed their babies so that they should not have jaundice. The mot-hers whose babies developed jaundice took their babies to a doctor as well as practicing several traditional beha-viors such as attaching a gold coin to their babies’ clothes, wrapping them with a yellow fabric or leaving the lights on. Some of these traditional practices done to prevent jaundice do not affect babies’ health and they do not prevent mothers from referral to a health center, eit-her. Wrapping babies with a yellow fabric or washing them with papaver juice does not prevent jaundice; however, they do not have any harmful effects. They incising the skin behind the ears or between the eye-brows, which were reported by other investigators from Turkey, may increase the risk of infections. For this reason, attempts should be made to change these traditional practices.

In this study, there was no significant difference bet-ween traditional child care practices and education, in-come, family type, origin and residence. It may be be-cause culture affects health behaviors more than demographics.

Public health nurses should be able to identify tradi-tional practices likely to cause risk for maternal and child health. They should consider the practices with no harmful effects as part of culture and should not be prejudiced about them in order to maintain communi-cation with individuals from different cultures and to win their confidence. The nurses should try their best to c-hange the traditional practices likely to put mothers and their babies at risk of diseases and to help mothers to acquire health promotion behaviors.

Conclusion

Under the influence of mores, traditions, customs and their parents, most of the mothers included in this study were found to perform traditional child care practices. The results of this study can help all health professionals to recognize the role of traditions in child health. Some of these practices have no negative effect on their babies. However, some traditional practices have harmful effects on babies’ health.

This study showed that the rate of women who start-ed breastfestart-eding early in the postpartum period was quite high, but that such traditional child care practices as app-lying salt on the neonates’ skin, swaddling, attributing disease symptoms to the evil eye and staying at home for forty days after birth in case of “kırk basması” are still common and harmful to babies. In order to change tradi-tional child care practices with harmful effects on mother and infant health, first, these practices should be identified as we did in this study. Then, the underlying causes of these practices such as the belief that these practices are helpful should be revealed. It can be sug-gested that culture and health beliefs should be taken into account when training programs are prepared to change traditional child care practices and to promote health behaviors.

Breastfeeding is particularly important in neonatal he-alth. Nurses should develop training programs to replace traditional breastfeeding practices with healthy breastfeed-ing behaviors. In order to develop such trainbreastfeed-ing programs, they need to know health behaviors of the communities they provide care for and respect the beliefs and practices unlikely to affect health to win the confidence of the com-munities.

Further longitudinal studies are needed to determine harmful traditional child care practices during pregnancy, to develop training programs to change harmful habits among prospective mothers and to evaluate effects of those training programs on behaviors.

The culturally specific knowledge obtained in this study should be disseminated among nurses to help them develop appropriate education programmes for postnatal care. Nursing education curriculums should be revised to enable nurses to assess if new mothers and their carers use traditional practices, to reinforce positive cultural practices and to discourage potentially harmful ones.

References

Aksayan, S. (1982). Traditional practices in mother and child health. Journal of Turkish Associate, 2(3), 37-39.

Aksayan, S., & Hayran, O. (1992). Health, disease and culture. Journal of Sendrom, February, 12-14.

Alp, H., Yaman, S., & Altınkaynak, S. (1993). Breastfeeding and health. Journal of Sendrom, 5(5), 59-61.

Bahar, Z., & Bayık, A. (1985). Analyses of traditional child care behaviors of mothers in Doğanlar. I. National Nursing Congress (Congress Book), Izmir. 13-15 September, 241-250.

Balıkçı, G. (09.12.2006). Beliefs and customs about birth in some parts of Trabzon. Accessed: 17 June 2007 from

http://www.folklor.org.tr/icerik/haber_detay.asp?id=88 Baltaş, Z. (2000). Psychology in Health (1st edition). Remzi

Publishing, İstanbul.

Bayat, A. H. (1987). Yellowness sicness and traditional therapy of Anatolia. III. National Turkish Folklore Congress (Congress Book), Ankara. 23-28 June, 47-66.

Biltekin, Ö., Boran, D. B., Denkli, M. D., & Yalçınkaya, S. (2004). Traditional practices concerning pregnancy and child care among mothers with Infants aged 0-11 months in

Naldöken Primary Health Care Center. Continuous Medical Education Journal, 13(5), 166-168.

Bohler, E., Semega, J., Holm, H., & Matheson, I. (2001). Promoting breastfeding in rural Gambia. Health Policy and Planning, 16(2), 199-205.

Choudhry, U. K. (1997). Traditional practices of women from India: pregnancy, childbirth, and newborn care. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, Principles & Practices, 26(5), 533-539.

Demographics and Health Survey made by Hacettepe University (DHS) (2008). Demographics and health survey, Turkey. Ankara, Hacettepe University, Institute of Population Studies.

Dinç, S. (2005). To determine the traditional practices which mothers, having 0-1 years old children, registered to health center no 4 in Şanlıurfa center. Society for Research and Development in Nursing, 1(2), 53-63.

Eğri, G., & Gölbaşı, Z. (2007). Traditional postnatal infant-care practices of 15-49 years old married women. Preventive Medicine Bulletin by Turkish Armed Forces Doctors, 6(5), 313-320.

Ergenekon-Ozelci, P., Elmacı, N., Ertem M., & Saka, G. (2001). Breastfeeding beliefs and practices among migrant mothers in slums of Diyarbakır, Turkey, 2001. Maternal and Child Health, 16(2), 143-148.

Fikree, F. F., Ali, T. S., Durocher, J. M., & Rahbar, M. H. (2005). Newborn care practices in low socioeconomic settlements of Karachi, Pakistan. Social Science & Medicine, 60(5), 911-921.

Geçkil, E., Şahin, T., & Ege, E. (2009). Traditional postpartum practices of women and infants and the factors influencing such practices in South Eastern Turkey. Midwifery, 25(1), 62-71.

Gözüm, S. (1992). What do mothers with 0-6-year-old babies provided care by Ceylanoğlu Health Center, Erzurum, know about child health? Nursing Department Unpublished Master Thesis, Atatürk University Health Science Institute, Erzurum, Turkey.

Lawn, J. E., Cousens, S., Bhutta, Z. A., Darmstadt, G. L., Martines, J., Paul, V., et al. (2004). Why are 4 million newborn babies dying each year? Lancet, 364(31), 399-401 Marsh, D. R., Darmstadt, G. L., Moore, J., Daly, P., Oot, D., &

Tinker, A. (2002). Advancing newborn health and survival in developing countries: a conceptual framework. Journal of Perinatology, 22(7), 572-576.

Mattson, S. (2000). Working toward cultural competence. AWHONN L i f e l i n e s, 4(4), 41-43.

Mullany, L. C., Darsmtad, G. L., Khatry, S. K., & Tielsch, J. M. (2005). Traditional massage of newborns in Nepal: implications for trials of improved practice. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 51, (2), 82-86.

Ofluoğlu, E., & Saruhan, A. (1995). Traditional cures used by mothers with 0-5- year-old babies. Nursing Department Unpublished Nursing Graduation Thesis, Aegean University School of Nursing, İzmir, Turkey.

Özden, T. (1987). Beliefs and traditions about pregnancy, delivery and lactation. Nursing Department Unpublished Master Thesis, Hacettepe University Health Science Institute, Ankara, Turkey.

Özkan, S., & Khorshıd, L. (1995). Beliefs and traditional practices among mothers with 0-1-year-old babies, Nursing Department Unpublished Nursing Graduation Thesis, Aegean University School of Nursing, İzmir, Turkey. Özyazıcıoğlu, N., & Polat, S. (2004). Traditional health care

practices among mothers with 12-month babies. Atatürk University School of Nursing Journal, 72, 63-71.

Platin, D., & Khorshıd, L. (1994). Analyses of traditional child care practices used by mothers with 0-6-year-old babies. Nursing Department Unpublished Nursing Graduation Thesis, Aegean University School of Nursing, İzmir, Turkey.

Reifsnider, E., Allan J. & Percy, M. (2000). Mothers’ explanatory models of lack of child growth. Public Health Nursing, 17(6), 434-442.

Reissland N., & Burghart, R. (1988). The quality of a mother's milk and the health of her child: beliefs and practices of the women of Mithila. Social Science & Medicine, 27(5), 461-469.

Sahinöz, S., Özçırpıcı, B., Bozkurt, A. İ., Özgür, S., Şahinöz, T., Acemoğlu, H., et al. (2002). Child nutrition related practices in GAP Region. Accessed: 25 June 2007,

http://www.dicle.edu.tr/~halks/m10.6. htm.

Savaş, G., Alpaslan, N., & Ağrıdağ G. (1994). A study on breastfeeding practices of married women provided care by Akkapı Health Center. IV.National Public Health Congress (Congress Book), Aydın. 12-16 September, 185-187. Sezen, L. (1994). Folklore of the city Erzurum (pp. 3). Erzurum:

Erzurum Progress Cognizant Publications. Dergiye geliş tarihi: 20.05.2010

Kabul tarihi: 01.07.2010

Taşdemir, M., Hayran, O., Akgöz, S., & Çalı, Ş. (1994). Traditional health care practices in Istanbul. IV.National Public Health Congress (Congress Book), Aydın. 12-16 September, 171-174.

Toksöz, P. (1992). Analyses of factors which affect mother and child health in Diyarbakır, Dicle University GAP Research and Application Centers, Diyarbakır, 64-67.

World Health Organization (WHO) / The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) (2000). Breastfeeding in 2000s. Ankara: UNİCEF Turkey Representation.

Winch, P. J., Alam, M. A., Akther, A., Afroz, D., Ali, N. A., Ellis, A. A., et al. (2005). Bangladesh PROJAHNMO Study Group. Local understandings of vulnerability and protection during the neonatal period in Sylhet District, Bangladesh: a qualitative study. Lancet, 366(9484), 478-85.

Yalın, S. (1998). Traditional patient care practices. Nursing Department Unpublished Nursing Graduation Thesis, Hacettepe University Health Sciences Institute, Ankara, Turkey.

Zoysa, I., Bhandari, N., Akhtari, N., & Bhan, M. K. (1998). Careseeking for illness in young infants in an urban slum in India. Social Science & Medicine, 47(12), 2101-2111.