Я Л ? и>· iá^-:ii.-iW.4v5j»·· :4>ΙΛ; Г“ J=;.J..3s=¿r\A ■*

'■^- >1 »·) і '·ί *ΐί ’tí· Itt ‘Ьш/. 4^ >;i? .'J ¿i? s ІІІШЛ Úlüis jiËûi Ёіікь. . ъЯ' ІЬк ІІ! İt î . ’î i ' i ı s M iï*s.PJi is'Pfîniï:f^:?'?? !>ψ « s a 53 S 3 ..■ -ï ·% . i: Î ·# .■ iШ TllKlifCV. ¿¡ ¿-i?· "‘v* •’İSİ'' U і;*А> «г Λ ;і T P i ï S i ê U li'.jy .ê-jj .¡цчі^І - U áí' I il^vi Ъ; ^ J J * , ϋ”!“ ІйЬГ·: '; .г1 ;:i ·:| í. ψ ■, í .s ;:·

IS CU L TU R E A SU P E R F I C IA L BA RRIER TO

GLOBAL MARKETING?: A CASE STUDY

OF FOOD AND DRINK PRODUCTS IN TURKEY

A THESIS

S U B M I T TE D TO THE D E P ARTMENT OF M ANAGE MEN T AND

THE G RA D UA T E SCHOOL OF BUSINESS A D M I N I S T R A T IO N OF

BILKENT UNIVE R S I TY

IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE R EQUIR E M E N T S FOR THE DEGREE OF

MASTER OF BUSINESS A D M I N I S T R A T IO N

BY

SİBEL SEZER JUNE 7,1989

H P / é

1

I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Business Ami ni stration.

Assist. Prof. Guliz Ger

I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a

thesis for the degree of Master of Business

Aministration.

Assist. Prof. Kiirsat Aydogan

I certify that I have read this thesis and in my ooinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a

thesis for the degree of Master of Business

Aministration. ,

L

ABSTR/KO-r

IS CULTURE A SU P E R F ICIAL BARRIER TO

GLOBAL MAR K E T I N G ? : A CASE STUDY

OF FOOD AND DRINK PRODUCTS IN TURK EY

SİBEL SEZER M.B.A. thesis

Supervisor: Dr. GULIZ GER

June, 1989

In a world of converging needs and desires,

globally s ta n dardizing products would lead to

lower production costs, improved quality of

products as well as management. The validity of

this a r g u m en t proposed by "global marketing" is

disc u s s ed taking into cons i d e r ati on the diff er e n c e s

e x i s t i n g within cultures and w hether culture is in

fact a barrier to globalization. A study was

cond u c t ed in order to e x p l ore whether global

mark e t i ng strategies can be successful in Turkey

for food and drink products c ompeting with local

c o u n t e r p a rt s with regard to age, sex and s o c i o

economic status comparisons.

Keywords: Globalization, Standardization, Culture,

Perception, Demographics,

OiTü E T

KÜ L T ÜR GLOBAL PAZA R L A M A İÇİN YAPAY BİR

ENGEL Mİ TEŞKİL E D E R MEKTE DİR :

T ÜR K İ Y E DEKİ BESİN Ü R ÜNLE R İ N İ N BİR İNCELEMESİ

SİBEL SEZER M.B.A TEZİ DR. GÜL İZ GER

h a z i r a n, 1989

İhtiyaç ve isteklerin bütünleştiği bir dünyada,

ürünleri evrensel çapta s t a n d a r t 1 aştırarak daha

düşük m a l i ye t t e üretim, daha üstün kalite ve daha

iyi bir işletme elde etmek mümkündür. Her kültürün

kendi içindeki f a r k l ı l ı k l a r göz önünde tutularak,

global p a za r la m a n ın ön görmekte olduğu bu a r g ü man ın geçerliliği t a r tı ş ıl m a k ta ve kültürün gerçek ten bir

engel o l uş t ur u p oluşturmadığı araştırı lmakt adır.

Global p azarlama s t r a t e j i s i n in Türkiye için geçerli

olup olmadığını öğrenmek amacıyla yabancı besin

ürünleri ile benzeri yerel ürünler tüketici

a çı s ı n d a n karşılaştırmalı bir araşt ırma konusu

oluşturmuştur.

“TABLE O E C O M T E M T S

A B S T R A C T ... i

OZET ... ii

A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S ... İİİ TABLE OF C O N T E NT S ... v

LIST OF FIGURES ... vii

LIST OF TABLES ... viii

I. INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 G L OB A L IZ A TI ON ... 2

1.1.1. Strategies dealing with Globa l i z a t i on ... 3

1.1.2. Standardization, C en t r a l i z a t io n and Differ e n t i a ti o n ... 5

1.1.3. Arguments For and A gain st Global Marketing ... 8

1.1.4. Some G u i d e l i n e s to S u c cessf ull y Achieve G l o b a l i z a t i on ... 14.

1.2. CULTURE AND M A R K E T I N G ... 15

1.2.1. The Study of C u lture ... 1 5 l' 1.2.2. C u l t u r e ’s Affect on Consumer Behavior ... 19

1.2.3. Culture, Soc i o - E c o nomic and

Dem o g r a p h i c Factors ... 21

I . 2.4 Semiotics and Culture ... 25

II. PRESENT RESEA RC H ... 28

1 1 . 1. THE PURPOSE AND THE H YPOTHESIS OF THE STUDY ... 28

1 1 . 2. RESEAR C H DESIGN AND ME T HODO LOG Y ... 30

I I . 2.1. Sample ... 30

1 1.2.2. Material ... 32

11 .2.3. Procedure ... 34

1 1 . 2.4. Results ... 35

1 1 . 2.4.1. Overall Usage Frequencies .. 35

1 1 . 2.4.2. Usage Frequencies Between D ifferent Levels of SES .... 37

1 1.2.4.3. Usage Frequencies Between Diff e r e n t Age Groups ... 37

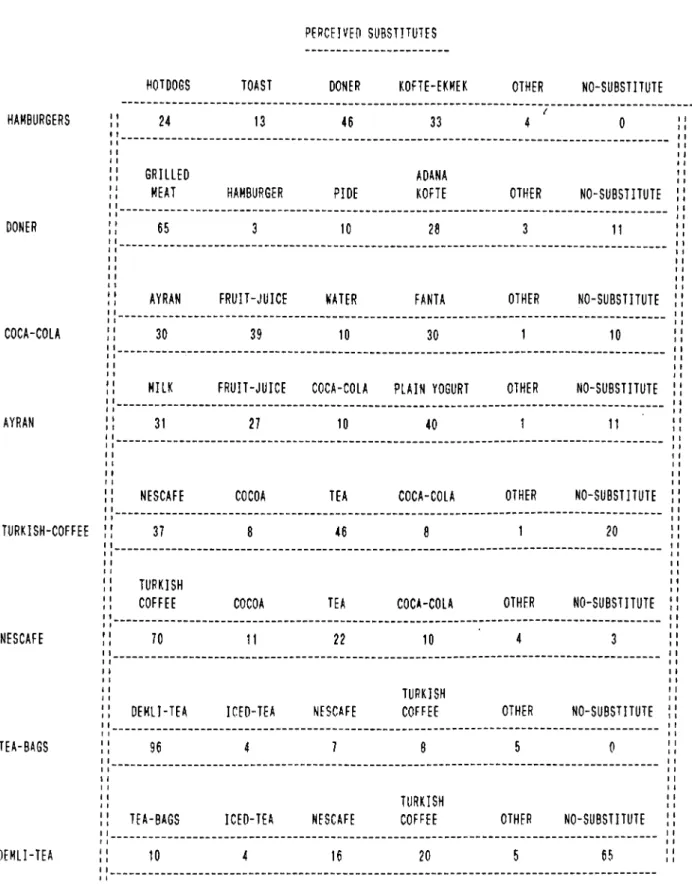

11.2.4.4. P erceived Substitutes ... 33

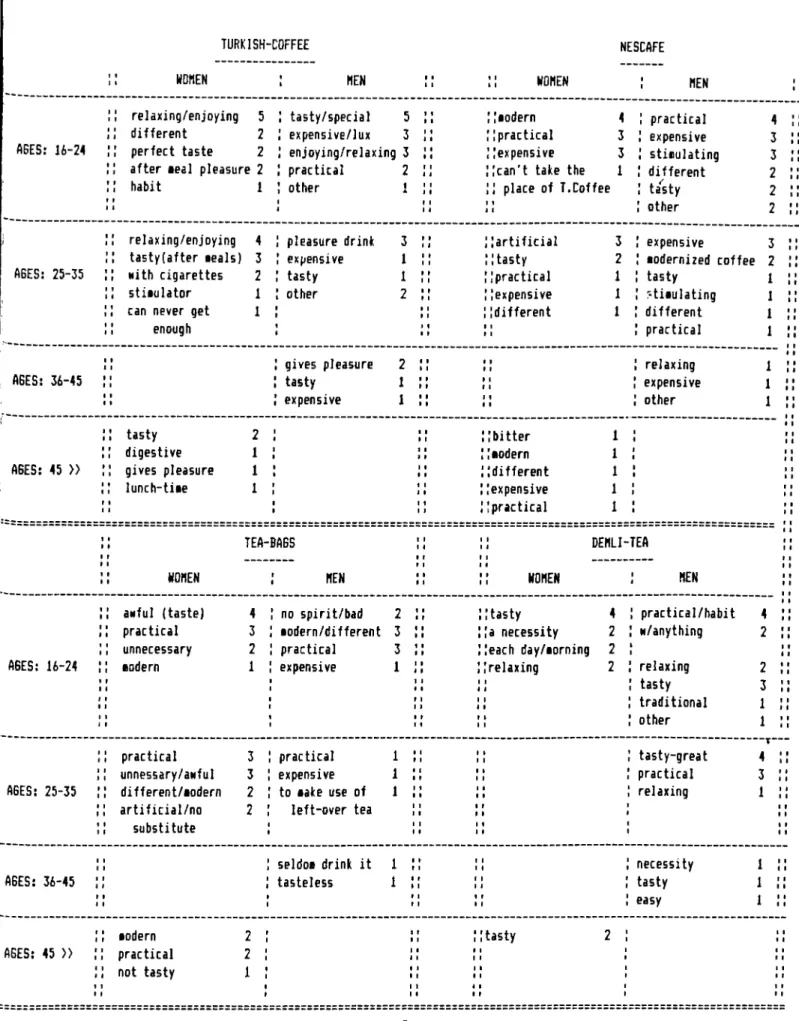

1 1 .2.4.5. P e r c e ptions Towards the Products Within Groups .... 39

11.2.4.6. Sex Differences Within Each Professional Group ... 43

II.3. DI SC USS ION AND CONCLUSION 44 RE F E R E N C E S 50 APPEND I X A - THE QU E ST I O N N A I R E 52 APPENDIX B - FIGURES 58 APPENDIX C - TABLES 82

VI

L I S T O R RTG5URES

FIGURE 1 - E v o l u t i o n a r y Stages of the Global Firm ... 59

FIGURE 2 - Multinational, Sub-Global and Global M a r k e t i n g S t r ategies ... 60

FIGURE 3 - R e l a ti v e A d va n ta g e s of S t a nd ardiz ation and D i f f e r e n t i a t i o n ... 61

FIGURE 4 - Geographical S t a n d a r d i s a ti o n ... 62

FIGURE 5 - P e r c en t ag e of Goods with very Substantial P r oduct S t a n da r d i z a ti o n ... 63

FIGURE 6 - O b s t a c l e s to S t a n d a r d i z i ng the Marke tin g Mix .... 64

FIGURE 7 - N o n - Pr i ce Co m p e t i t i v e Tools Used by U.S. Firms ... 65

FIGURE 8 -A - W o m e n ’s Perception Towards Hamb u r g e r s ... 66

B - M e n ’s P e r ception Towards Ha mb u r g e r s ... 67

FIGURE 9-A - W o m e n ’s Per ce p t i o n Towards Doner ... 68

B - M e n ’s Perception Towards Doner ... 59

FIGURE 10-A - W o m e n ’s Perc e p t i o n Towards C o ca-C ola ... 70

B - M e n ’s Pe r ception T o wards C oc a-Col a ... 71

FIGURE 11-A - W o m e n ’s P e r ception Towards Ayran ... 72

B - M e n ’s Per c ep t i o n Towards Ayran ... 73

FIGURE 12-A - W o m e n ’s Per c e p t i o n T o wards Nescafe ... 74

B - M e n ’s Perc e p t i o n T o wards Nescafe ... 75

FIGURE 13-A - W o m e n ’s P e r ception T o w a r d s T u r k i s h - C o f fe e .... 76

B - M e n ’s P e r ception T o wards T u r k i s h - C o f fe e ... 77

FIGURE 14-A - W o m e n ’s P er ception T o wards Tea-Bags ... 73

B - M e n ’s P er ception T o wards Tea-Ba gs ... 79

FIGURE 15-A - W o m e n ’s Pe r ception T o wards D e mli-T ea ... 30

B - M e n ’s Perception Towards D e mli- lea ... 31

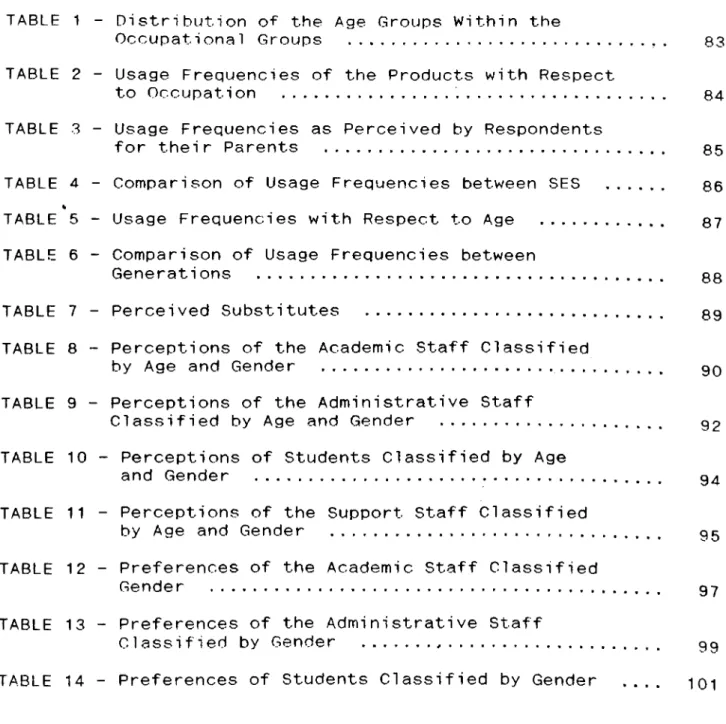

L I S T O F t a b l e :

TABLE 1 - D i s t r i b u ti o n of the Age Groups Within the

Occupational Groups ... .

TABLE 2 - Usage Frequencies of the Products with Respect

to O c c up a ti o n ... ...

TABLE 3 - Usage Frequencies as P erceived by Respondents

for their Parents ...

TABLE 4 - C o m p a r i s o n of Usage Frequencies between SES »

- Usage Frequencies with R e spect to Age ...

- C o m p a r i s o n of Usage Frequencies between

G e n e ra t i o ns ...

- P e r c e iv e d Substitutes ...

- P e r c e pt i o n s of the Academic Staff C las sifie d

by Age and Gender ... ...

- P e r c e p ti o n s of the Adm i n i s t r ative Staff

C l a s s i f i e d by Age and Gender ...

- Pe r c e pt i on s of Students C l a ssified by Age

and Gender ...

- Pe r ce p t i on s of the Support Staff Cl ass ified

by Age and Gender ...

- P r e f e r en c es of the Acade m i c Staff Class ifi ed

Gender ...

- Pr e f er e n c es of the A d m i n i s t ra tive Staff

C l a s s if i e d by Gender ... ...

- Pr e f er e n c es of Students C l a ssified by Gender TABLE 5 TABLE 6 TABLE 7 TABLE 8 TABLE 9 TABLE 10 TABLE 1 1 TABLE 1 2 TABLE 13 TABLE 14 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 92 94 95 97 99 101

VI 1 1

This study intends to explore the question of

w h e t h e r global m arketing s t r ategies are appli cable

t h r o u g h o u t the world. Part I, which is largely

theoretical, ap p roaches the question of globalization by

focus i n g on several relevant issues. These are, namely,

the st r a t e g i e s that deal with globalization; the concep ts

of standardization, c e n t r a l i z a t io n and di fferentiation and

what they represent; a rguments made by the leading

advo c a t e s for and a gainst global marketing; and, some

guid e l i n e s to succe s s f u l l y achieve globalization.

Secondly, Part I deals with how m arketing and culture are

related. Under this title, an overview of the study of

c ulture is presented, including the socio- eco nomic and

d e m o g r a p h i c factors influencing culture, followed by an

e la b o r a t i o n of c u l t u r e ’s affect on consumer behavior.

Part II, which is empirial, begins by ex plaining the

purpose of the survey that has actually been conducted in

order to test certain h y p o thesis relating to our basic

question. The hypothesis are followed by research design

and m e t h o d o l o g y which include the sample, material,

p rocedure and results. The final section includes the

d i s c u s s i o n and conclusion.

I. INT RO DU CTI ON

1.1 G L O B A L I Z A T I ON

Global m arketing is a very popular topic in which

cu rrent debates take place on its a p pl icabi lity regardless

of the c o untry targeted. A related issue is whether the

future m a rk e t i n g s t rategies should pursue a standardised

or a localized strategy for the m arkets considered. In

this study, issues regarding global marke tin g strategies

and their relation to culture are discussed. A survey is

used to e x p lo r e whether global marketin g strategies are

successful in Turkey for products competing with local

c o u n t e r p a r t s and whether culture is a possible barrier to globali z a t i o n .

The c o ncept of g l o b a l ization ori g i n a t e s from the

evolu t i o n of the world economic system, that is the

evolu t i o n from trade to foreign direct investment up to

globalization. Countries, esp e c i a ll y England and Holland,

realized the importance of trading with foreign c ountries

starting f r o m the sixteenth century on. The successful

firms of the home country realized they could enlarge

their profits by seeking o p p o r t unit ies abroad. Black

(1986) is among many who emp h a s ize s the role of mass

pro du c t i o n in the ability to sell abroad. When a country

mass produces, an abundance of products produced arise due

to increased e f fi ciency in which case e xporting proves

profitable. As the number of nations exportin g increases,

barriers such as tariffs and quotas. These devel opments

give way to the multinational firm. The multinational

firm is d e fined as evolv i n g seperate international

divisions acting as s e m i - i n d e p e nd e n t o perating units

focused upon their p a r ticular countries with key

co m p e t i t o r s defined in relation to each seperate market

(Halliburton and Hunenberg, 1987). Finally, the last

stage along this c o n t i n u u m is global m arketing for which the a r g u m e nt is that the most suitable method to deal with rising costs of producing for seperate markets would be to produce a p r od u c t in high qua n t i t i e s which would meet the

demand of the entire world. Kaynak (1987) provides a

summary of the stages involved f rom initially producing solely for the home e c o n o m y towards producing global products (Figure 1).

The c o ntent of co m p e t i t i on changes depending on

the strat e g y of the firm, that is to say, whether it is

local, multinational or global. In export markets the

c om p etition is in the home country from which it exports; in the multinational firm c o m p e t i t i o n is seperate in each

seperate ma r ke t it operates; and, in the global market

co mp e t i t i o n is global.

1.1.1. Stra t e g ie s Deali ng with Globali zation

Mesdag (1971) argues that the strategy of

trying to sell a successful product in the country of

trying to discover the needs (manifest or latent) of that

particular country, can be called "The shot- in- the-d ark

m e t h o d ” , and is an "unmarketing" approach. The strategy

is based on the premise, or the hope that the

d o m e s t i c a l l y successful p r oduct will sell abroad. More

ap pr o p r i a t e stra t e g ie s to deal with international markets

are the multinational strategy, the sub-global strategy

and the global strategy.

The multinational strat e g y treats the world in

seper a t e m a rk e t s and thus uses differ ent ma rketing

strategies in each ma rk e t it operates. Farley (1985) says

that "companies pursuing the multinational strategy ignore s i m il a r i t i e s and c o n c e n t r a t e on di ffe rence s in their

operational policies and programs." Ignoring

s i m i l a r i t i e s may be due to the realization that even

if si m i l a r i t i e s exist, they may not be suff icien t to

provide the firm with the n e cessary sales in those

countries. Thus, c o n c e n t r a t i n g on dif feren ces may

prove to be more profitable.

The Sub-Global Stategy tries to meet the

e x p e c t a t i o n s of the international product while satisf ying the needs of different target groups such as d ifferent

cultures, e c o n o mi c status or d e m o g raph ic areas. A lthough

basic human needs are the same t h r o ugh -ou t the world, the

symbols in which they are interpreted and the ways they

are sati s f i ed differ between d i f f erent cultures. Thus,

the e x e c u t i o n s of the p r oduct having basic global appeals.

The Global Mark e t i n g Strategy argues for globally

s t a n d a r d i z e d products because they satisfy the consumer

with regard to lower cost, improved quality and

management. The products would benefit from econo mies of

scale, as well as from the transfer of ideas. Thus, a

f irm with a su c c e ss f ul l y mass produced product in its home c o untry can mass produce it t h r oughout the entire world.

It is argued that technology has become the power whi c h drives the world "toward a converging commonality"

(Levitt, 1983). Accordingly, the technological

d e v e l o p m e n t s that took place in transportat io n and

c o m m u n i c a t i on have led to products which are d esirable

t h r o u g h - o u t the world. This has enabled many diff ere nt

c u l t u r e s of varying c ountries to experience and thus become f a mi l i ar with a wide array of foreign goods. C e r t a i n barri er s exist such as different ma rket and

industry characteristics, legal restrictions and company

o r g a n i z a t i o n (Buzzell, 1968). These three m a r k e tin g

s t r at e g i e s for international sales are illustrated in

Figure 2 (Kaynak, 1987).

1.1,2. S t a n d a r d i z a t i o n . Centrali zation and P i f f e r e nt iatio n

Global m a r k e t i n g strategies are linked to the conce pts of

standardization, cent r a l i z a t io n and differentiation.

S t an d a r d i z a ti o n implies a common marketi ng "mix"

to another. C en t r a l i z a t io n refers to organizational stru c t u r e and decision-making. Thus, sta ndar d i z a ti o n is an

external m a r k e t i n g question, w h ereas c e n tra lizat ion is

specific to the o rg a ni z a t i o n and is t herefore an internal

question. S t a n d a r d i z a t i o n implies a higher degree of

c e n t r a l i z a t i o n but the opposite does not have to hold t r u e .

If st a n d a r d i z a t i o n is found to be inappropriate,

the products m u s t be adapted with regard to market needs

of the co u nt r y being targeted. The "degree of

adaptation" is of concern once a decisio n has been made

that s t a n d a r d i z a t i o n will not be a ppr opriate for the

product. A d ap t a t i o n can be in several c o m pon ents such as

packaging, pricing, distri b u t i ng as well as the

ingredients, or the combination of certain ingredients.

Differentiation, unlike standardization, implies marke tin g

the p r oduct to diff e r e n t segments on the bases of

m a r k e t i n g activities. Mark e t i n g a ctivities have been

cla ss i f i e d on three levels. The first is the m a r k et ing

strategy in which the m a r k e t e r selects certain target

groups and sati sf i es their specific needs in order to gain

a c o m p a r a t iv e advantage. The second activity is the

marke t i n g mix which is composed of price, product,

p romotion and distribution. The third group of act iviti es

are the m ar k e t i n g procedures whi ch are organisational procedures, information, planning and control (Halliburton

international m a rkets with regard to the levels of st a n d a r d i z a ti o n and di f f e r e n t i a ti o n are depicted in Figure 3 (Halliburton and Hunenberg, 1987).

Resear c h findings suggest that the overall

marke t i n g o b j e c ti v es and strategies as well as the

m ar k et i n g pro c ed u r e s are more easily standardized than the

m a r k e t i n g mix elements; and, that with the marketing mix,

the seque nc e of ease of s t a n d ardization starts from

product decisions, followed by promotion and advertising,

deci s i o n s (Walters, 1986).

No strict rules exi s t as to whether s tanda rdi zatio n

or d i f f e r e n t i a t i o n is appropriate. The relevant question

is the degree of each to be applied. An ex amp le of

a d v er tising as an instrument; and cultural co ntext as a

mark e t i n g o b j ec t i v e is illustrated in Figure 4

(Halliburton and Hunenberg, 1987) with the degree of

g e ographic standardization.

It has been found that st andar diz ation is

relatively high and growing for certain industries

(Boddewyn et.al., 1986) An investigation of the U.s.

compa n i e s in the European Economic Commu nit y (EEC)

indicate a slight increase in product st and a r d i z a ti o n

from 1973 to 1983 in consumer durables, a substantial

increase in nondurables, and a decrease for industrial

products wi th i n the same time period (see Figure 5 ). A n t i c i p a t i o n of a more s t a ndardized marketing mix for five

s t an d a r d i z a ti o n that took place for consumer durables and industrial goods.

They also found that "the standar diz ation of product,

brand, and adv e r t is i ng do not necessarily move apace, and

that a d v e rt i s in g is more resistant to uniformiz ation than are the other two" (Boddewyn et.al., 1986).

1.1.3. A r g u m en t s For and A g ainst Global Marketing

There are two major view points on the question of

the relevance and merits of global marketing. While one

view supports the concept and strategy of global

marketing, the second one argues that global mark eting is not suitable to the realities of a multi-cultural world. These argu m en t s are s u m m arized below.

The su p porters for global market ing

argue that the w o r l d ’s needs and desires are becoming very

similar, and a cultural c o n v e rgence is taking place. For

example, Levitt (1983) d e scribes this c o n v erg enc e by

pointing out the increased w o r l d w i de communication. "The

same c ountries that ask the world to recognize and respect

the individuality of their cultures insist on the

whole s a l e tran s f e rs to them of modern goods, serv ice s and

technologies" (Levitt, 1983). Kaynak also e m p h a s i z e s

the "homogenized" world needs. He argues that the

television programs and motion pictures shape shared

cultures, and that the use of L-SAT high power TV

satellites mig h t eve n t u a l l y get rid of cultural barriers

(Kaynak, 1987). Thus, c u lture is viewed to be a barrier

that can easily be overc o m e in our modern world. Cultural

factors are c o n c ep t u a l i ze d as being superficial and that

cultural preferences, national tastes and standar ds as

being v e s t i g es of the past (Levitt, 1983). A more

flexible u n de r s t a n d i ng towards p ref erences and needs of cons u m e r s from varying cultu r e s may yield profitab le

results. Thus, mark e t e r s may realize the other side

of the coin: that p r ef e rences are homogenized.

Furthermore, the s u p p o r t e rs of global ma rketi ng

argue that international c o m p e t i t i o n will force

g l ob a l i z a t i on (Levitt, 1983; McNally, 1986). The global

firm will totally sp e cialize on one thing and e ven tuall y

gain great e x p e r t i s e and k nowledge on it. By using "high-

tech" m e t ho d s and benefiting f rom econ omies of scale the

global firm will be able to m a n u f a c t u r e high quality at

very low costs. Studies (e.g. Levitt, 1983; Keegon, 1987)

argue that c o n s um e rs are influenced greatly by low price regardless of features and heavy prom oti on regardless of

price. Thus, high quality toget h e r with low prices may be

strong enougn incentives to break down barriers such as

culture. The question persists as to the time needed to

a c hieve low price and high q u ality simultaneously.

Japan e s e firms have been w o rking towards this goal for

many years. As they have been producing low-cost

tech n o l o g y and highly a utomated factories, they obtained

believes that unless the afflu e nt U.S. firms do not go

global they will not be able to compete in our

inter n a t i o nall y competitive age, especially now that

a g r e s s i v e l y competing in global markets is becoming a national o bj e c t i v e for many countries.

On the other hand, many criticisms are raised

against these arguments. For example, Boddewyn

et.al. ( 1 9 8 6 ) argue that the evide nc e in L e v i t t ’s article

is as sc a r c e as the beef in the now famous W e n d y ’s

commercial. If the world is in reality becoming a

"global village" then pr a c t i c a l ly every product would

benefit f rom standardization. However, this statement

sounds u t opian due to very o b vious obstacles such as the varying d e grees of d e ve l opment between countries and the e xt e n t to whic h they can benefit from technology.

Nevertheless, even those w ho strongly reject the

co ncept of globalization, accept the fact that global

m a r ke t i n g str at e gi e s are suitable for certain industries such as for high technology, rapid innovation products and the truly international consumer products such as C o l a ’s. C e rtain e x a m p l e s are given of firms which have taken adva nt a g e of these di s t i nction cited above (Keegon, Still

and Hill, 1987; Kotler, 1984). Hilton and Gilette serve

the mo b i l e businessmen and tourists; Marlbor o and L e v i ’s

(Western Cowboy), Coca - C o l a and hamburgers (American

co n su m p t i o n habits). Hertz and Pan-Am (U.S. service

efficiency) all take a dvantage of the strong and favorable 10

U.S. image. Other ’’global" produc ts target the same consu m e r s e g m e n t whose purchasing moti ves and product-use

habits are similar t h r o u g h - o u t the world. Examples of

such produ c ts are baby food p roducers such as Gerber baby food; p h a r m a c e u t i c a l s which target health related problems;

and, Rolls-Royce, French Cha m p a igne and Russian Caviar

serve the el i t i s t segments (Keegan, Still, and Hill,

1987). Agnew (1986) also argues that the industries

s p e c i f i c a l l y a p pr o priate for global marketing are fast food and beverages, automobiles, airlines, packaged goods,

m a n u f a c t u r e d goods, and consumer goods of general use. In

general, though, st a nd a r d i z a ti o n for markets that show

marked national d i f f e r e n c e s are inappropriate and the

"whole global mark e ti n g craze is a ploy by advertising

agencies to get new business" (Kotler, 1984).

The ones who reject global marketing believe that comp et i n g all over the world at the same time may yield

more harm than profit (Black, 1986; L e n r o w ,1984). The

firms that wish to become world brands are advised to resolve the language, product, p r oduct usage, competition,

target groups as well as socio-economic, cultural and

technological di ff e re n c e s among nations (Lenrow, 1984).

Accordingly, Black (1986) advises that one should "think

globally and promote and sell locally".

Sup p or t for these c o n c e p t i o ns seem to be provided

by a study in which the participants, who are managers

asked to rate obstacles to s t a n d a rdizing their marketing

mix in the EEC (Boddewyn et a l , 1986). The largest

o b s ta c l e was found to be that of national difference s in

tastes, habits, regulation and technical requirements

(See Figure 6 ).

In addition, price was not found to be a major

c o m p e t i t i v e tool for 58% of consumer nondurable, 50% of

the durables, and 61% of the industrial goods. The non

price c o m p et i ti v e tools used by U.S. firms are depicted in

Figure 7 ( Boddewyn et a l , 1986). These findings suggest

that lower prices, which were argued to be one of the

crucial a d vantages that would be sought for by the global

consumer, may not in reality be the most critical

attr i b u t e desired. Thus, even though very low prices are

o b t a i n e d by the use of advanced technology and mass

production, the “global" consumer may prefer a slightly

higher priced local product because he believes it is

heal th i e r or has higher quality. However, these findings

do not indicate whether c onsumers would prefer a global pr oduct w ith extremely high quality as well as low prices to a local product he is accustomed to using.

According to Locke (1986), c ulturally

d e t er m i n e d attitudinal conflicts constitute a threatening

barrier in global marketing. He observed that "...those

hidden d i f f e r e n ce s -t h e ingrained socio-cultural patterns,

biases, customs and attitudes we all bring to every aspect

of our 1 ives-represent the global m arketing c o n c e p t ’s

fatal flaw". He points out that two con str aints have to

be exami n e d before global m a r ketin g st rategies are

considered: First, the instinctive sensitivity of people

who grew up in the same ma r k e t environment; second, enough market research to uncover c u s t o m e r s ’ needs.

In summary, supporters of global m arke tin g argue

that glob a l i za t ion will provide better quality with

reliability at lower costs because it will speci ali ze on

one p a r ticular c o mmodity for the wor ld consumer. O ther

a dv a ntages stated are the increasing degree of managerial

control, simplifying strategic planning efforts, taking

a dvantage of the home-c o u n t r y h e a d q u a r t e r ’s expertise, increased simplicity in dev e l o p i n g specific s ubs trate gies

(e.g. packaging, promotional, pricing, distribution), and

an overall reduction in problems resulting from ov erlaps

created by misusing both human and material resources

(Friedman, 1986). It is pointed out that the facts

indicated, along with advanced c o mm unica tion practises

going on t h r oughout the world are suff icien t to break

cultural barriers. On the other end of the pole are

advocates who argue ag ainst g l o b a l izat ion indicating that

societal differ en c es such as socio-cultural patterns,

biases, language, compet i t i o n and technology are inherent

in the society, i.e. they have been with the particular

culture for generations and thus are almost impossible to b r e a k .

to satisfy the c o n s u m e r ’s needs and wants. Thus, producers should not try to sell what they produce in the global context, just be global, but pursue globaliz ati on if

it fits with the c o n s u m e r ’s needs and desires. They

should sell their global products keeping in mind the

ch a r a c t e r i s ti c s of the culture they are targeting. In the

following sections, we should consider the various aspects of culture that might have important impacts on mar keting s t r a t e g i e s .

1.1.4. Some Guideli nes to Successful 1v Achieve Globali zation According to Ha l l i b u r t o n and Hunenb erg (1987) a firm should evaluate itself on the basis of certain rules in order to successfully apply s t a n dard iza ti on and thus

they identify nine guidelines. First of all,

s t a n d a r d i z a tio n is more applicable when marketing

obj ec t i v e s and strategies are taken into a ccount than the

marketing mix operations. Second, market ing procedures

and processes can be relatively sta ndard ise d while

retaining differen t ia te d m arketing mix operations. Third,

in the m arketing mix instruments, product deci sions such

as positioning, branding and p ackaging are the first to be st andardized followed by c o m m u nication decisions such as

the message and media, then by the sales force decisions,

di s tribution decisions and finally by the pricing

decisions. Fourth, ma r k e t leadership is necessary to

prolong global success. Leadership can be in size

cost, mass volume, industrial products); innovation

(value-added, hi-tech products); p erceived quality (added

value, mark e ti n g driven consumer goods). Fifth,

s t a n d a r d i z a ti o n of industrial and h i g h -t ech nolog y products

are more suitable to world conditions. Sixth, global

o p p o r t u n i t i e s are constrained by global competition.

Seventh, g lobalization is facilit ate d the greater the

c o n v e r g e n c e of customer demand and attitudes. Eighth,

g l o b a l i z a t i on is facilitated the greater the trade

patterns and the lower the trade restrictions. Finally,

more ce n t r al i z e d organisational stucture and proced ures are required for standardised approaches.

Altho u g h several guidelines have been sugges ted to

s u cc e s s f u l l y achieve globalization, there cerainly exists

certain barriers that are d i fficult to overcome. Cultu re

is one of the most critical barrier and thus shall be

exami n e d in more detail in the f ollowing section.

1.2. C U L T U R E AND MA R KETING

1.2.1. The Study of Culture

Althou g h as human beings we all have certain needs

or values that are crucial for survival, the means in

which we satisfy them differ across cultures. For

example, a basic inborn drive is hunger. What is

fas c in a t i n g is that we learn to eat certain things but

never to touch others. In Turkey, we learn not to eat

Europe is sold in the Turkish markets, it could only have

the few non-re l i g ou s as its customers. If we are hungry,

we turn to other types of food to satisfy our hunger. D i f fe r e n t cultures of the world prefer d ifferent types of

food, varying in taste. There are hundreds of different

cuisines in the world. Although every human being has a

tongue, and everyone uses it to communicate, not everyone

uses the same language in doing so.

C u lture is defined as the composition of the

learned programs for action and understanding that is

socially t r an s mitted from one generation to the next

(Linton, 1936). In the environment, the factors

influencing our learning process are the complex m essages

and signals, rights and duties, roles, tastes, habits,

regulations, language as well as institutions within our

s ociety ( D ’A n d r a d e , 1981). Thus, culture is also a part of

c o g n it i v e de ve l o p me n t as it primarily deals with shared

information upon which cognitive processes operate.

C e rtain forms of behavior are learned by a process of

repeated social transm i s s i o n ( D ’Andrade, 1981) By this

process the human brain is protected from overload pre ve n t i n g it from making an effort to learn.

The a s similation of the cultural traits by the me m b e r s is not always a concious and directed process.

For example, children do not always learn how to behave

by the use of strict guidelines but there are some types

of information available to lead them on. In other words.

there are indirect guidelines such as observation of adults or finding out that certain behaviors are not treated with sympathy but may result in pu nishment of some

sort. Thus, a child mostly learns the cultural traits by

imitating the adult models and by the reinforcements

given for ap p ro p ri a t e behavior.

Before the role of mores, norms and values in

culture are discussed, a brief review may be helpful in

clarifying our u nderstanding of these concepts. Mores

have the most powerful social influence among the three.

Everyone is expected to c o nform to mores which are

unwritten rules that the society e x pects the individual to

obey. Their power derives either from the fear of

punishment by law or fear of puni shm ent by social

pressure that would ensue breaking the s o c i e t y ’s ’'taboos” . A fre q u e n t l y given example of a taboo is eating human

flesh known as can n i b al i s m (Robertson, 1981). Norms, on

the other hand, are only gui deli nes to appropriate

behavior in a particular situation. Hence, in marketing a

global product, the firm can find ways around the norms

around a particular society if ap pro priat e strategies are taken but can do nothing to modify or change mores.

Soci e t i e s generally feel sel f -rig hte ou s about their particular ways of thinking and behaving while being

scornful or critical of the norms of others. In a sense,

there is an aspect of inevitability about s o c i e t i e s ’

guidelines as norms do; they are more general concepts.

Social values ev e ntually create norms. Like norms,

values are also regarded by the society that holds them as the only proper and a c c e ptable way of thinking and

behaving about particular situations. Un conditioned

respect for o n e ’s own values is generally equated with

ethnocentrism. E t h n oc e n t r i sm is defined as the evaluation

of the traits of another culture by the standards of the

own culture (Roberston, 1981) An thropologist Linton

(1966, p p . 6 6 ) observed:

It has been said that the last thing which a dweller in the deep sea would discover would

be water. He would become conscious of its

e x i s t en c e only if some accident brought him to

the s urface and introduced him to air. The

ability to see the culture of o n e ’s own society as a whole ... calls for a degree of o b j e c ti v i t y which is rarely if ever achieved.

For an example of ethnocentrism, one can cite the

case of how m a ke-up and jewelry used by women in two diff er e n t cultur e s can be viewed in two opposing ways: favorably for o n e ’s own but unfavorably for the other

society. For example, the European women place metals

through their ears and wear cosmetics on their faces

because they enhance their beauty; in contrast, the

Europeans think that the African women, who stick bones

through their noses and cut scars on their faces but due

to their ignorance, they do not realize how ugly they

become (Robertson, 1982).

I.· 2 . 2 . C u lture * s Affect on C o n s u m er Behavior

How does culture relate to consumer behavior? People living in diff e re n t cultu r e s tend to live their lives

under the domina n t influence of the values, norms and

mores of the society. Altogether, they usually add-up to

a life-style. Thus, c u lture affects p e o p l e ’s and

i n d i v i d u a l s ’ p r ef e rences and tastes. Accordingly,

d ifferent s ocieties may enjoy d i f f e r e n t products.

C o n s u me r s in varying c ult ures enjoy different drinks at meals although they may have to choose from the

same variety of drinks. People w ear d i ff ere nt styles of

clothing and prefer diff e r e n t types of e n t e r t a i n e m e n t , The p r e f erence of colors in funerals and weddin gs may be

totally oppos i ng in two cultures. If a firm producing

black w e d di n g gowns in its home country attempts to go

global, it would undoub t f u l l y prove to be an unsuccessful

strategy. One culture may find it proper to drive on the

right-hand side of the road whi le another culture may

prefer to drive on the left-hand side. Thus, a successful

British car company p roducing cars with the steering wheels on the right-hand side of the cars should think twice if he believes that s t a n d a r d izi ng his product would

increase his profits. Fasting may be perceived to be

superficial and silly in one s ociety and a crucial

necessity of life in another. A society may hold a

totally diff e re n t idea, or belief about what is

For example, the norms of the Menawei of Indonesia require women to become pregnant before they can be considered

eligi b l e for marriage; the norms of the Keraki of New

Guinea require premarital h o m o sex ual ity in every male

(Robertson, 1982). In contrast, Turkish norms forbid

premarital sex. These are very sensitive cultural

di f fe r e n c e s in which an u n a p p r o p r i a te advert ise ment could be s u f f i c ie n t to insult the society and thus should be selected with care.

There are a wide array of examp les that can be given in order to indicate how d i f f erent societies behave

and how u nsimilar they perceive similar behaviors. One is

an ad v e r t i s e m e nt for Ego, a new deodaran t brand that was

being a d v ertised in an A f rican country. The t elevision

commercial showed a short, fumbling man failing to be

sexually s u c e s s f u l , in a harem full of women. After

applying Ego, the women pulled him inside the tent and

ov e rp o w e r e d him. It was a very successful ad among the

white, but a failure among the black consumers. The

reason is that, in the African culture, deodorant does

not have the same sexual c o n n o t a t i o n s for blacks as it

does for whites. In their culture, there is a strong

belief that weak men are not respected. A man

o v e r po w e r e d by women would be acce pti ng that he was a weak person and thus would not be respected! Thus, the cultural traits are somewhat unique since they are rooted in

history, education, econ o m i c s and legal systems of the

relevant culture (Mesdag, 1987), and may lead to opposite

reactions to identical stimuli. Another example of an

unsuccessful attempt is made by General Foods in the

1960s. Having made a success with its nondairy whipping

cream, G.F. introduced the identical whipping cream to the

Swedish Consumer. Swedish women take pride in their

deserts and thus refused to use an artificial product

(Runyon and Stewart, 1987). The American consumer thus

peceived the c on v e nience of the p roduct to be a favorable

differential advantage and very beneficial as opposed to

the Swedish consumer who may have taken it as an insult. In the above sections it has been demonstrated that it is rather dangerous to treat one particular country as

a ho m o g e ni z ed market, let alone the entire world.

Accordingly, segmen t at i o n or adaptation strategies have

been put forward in order to deal solely with consumers

who have varying tastes, needs and preferences, that is,

with the assu m p t io n of no individual has identical needs,

desires, preferences, dreams, etc., with another

i ndividua 1 .

1.2.3. C u l t u r e . Soc i o - e c o n o mi c and Demographic Factors

An important issue is w h e t her everyone in a given society compl ie s with its culture, that is, with its norms

and values. The dominant culture has many su b-cultures

that have their own distin c t i v e values and norms. If the

diffe r e n t f rom that of the dominant culture, conflict may

arise. For example, a non-religous group may exist within

Turkey who reject the religous norm that eating ham is

sinful; thus may consume ham. In addition, major

normative dif f er e n c es are observed between different

social classes, for example, on how to raise daughters

and the e xt e n t to which girls may be liberated in the

We stern sense. Thus, consumers f rom different s oci o

econo m i c and e ducation levels and hence different life

styles may have varying c o n s u mption levels as well as

pe r c e p t i o n s towards products.

Regional marketing is argued to be a necessity in

order to increase sales of national brands (Edmonson,

1988; Carpenter, 1987; Moore, 1985). Firms learn to

compete with local competitors in each region and

di s c o v e r i n g new areas to compete by revealing facts of life

about consumers, lifestyle surveys that uncover consumers

desires, media monitors and sales records on each

individual m ar k e t (Edmonson, 1988; Carpenter, 1987). The

leading U.S. national brands are not market leaders in all

regions of the U.S.: for example, while Kraft Miracle

Whip is the national best seller in mayonnaise it is only mu n be r three in the North East competed out by H e i l m a n ’s

who is the regional leader (Edmondson, 1988). Data

collected by a subsidiary of Time Inc. reveals No.1

ma rkets for selected products. For example. Coffee sells

most in Pittsburgh; Iced Tea in Philadelphia; Vitamins in

Denver; T oo t h b r u s h e s in Seattle, and so forth ( Moore,

1985). It wou ld have been a fa s c i nati ng study if the data

had been coll e c t ed to reveal the c ountries in which each

product was found to be most popular! The study hints to

the m a g n i t u de of assumptions one must take in order to go g l o b a l .

On the other hand, one must be careful not to

e x plain all differences in preferenc es and tastes by

cultural differences. Soc i o - e c o n omic differences such as

d i f f e r e n c e s in per capita income among societies also

influence tastes and choices. In other words, it is

d i ff i c u l t to measure the extent to which cultural factors

influence behavior independent of income. For example, it

is said that only in the U.S. people are interested in

newly innovated products with gadgety quality. Perhaps if

electrical knives were offered for a low price in Turkey

it would become very popular.

A n other means of exp l a i nin g the relevance of culture to consumer behavior is by the use of Maslow.’s

H ie r ar c h y of needs, which is a universal hypothesis

(Keegon, 1974). In the h ierarchy of needs, an

individual first satisfies the physiological needs such as

food, wat e r and air. As soon as the lower needs are

satisfied, s/he goes on to fulfill the next steps on the

hierarchy, which are safety needs, belongingness needs,

es t e e m needs and self - a c t u a l iz a t i o n needs respectively.

social and economical welfare of a country, the higher the

level of needs mostly attained to; and the lower the

welfare, the lower the needs that will be attained to.

Thus, the consumer needs and desires may vary with respect

to the d ifferent cultures of differ ent social and

economical welfare conditions of a particular country,

and thus, have noteworthy d i fferences that might

co n stitute an important barrier to global marketing.

There are certainly exeptions to this hypothesis in which the even the poorest countries feel the need to fulfill

the upper needs on M a s l o w ’s Hierarchy. For example, "kan

davasi" is very frequently heard of in the p oorest regions

of Turkey. The poor Turkish families take revenge from

one another because they believe or feel that their honor

has been destroyed, or has become ‘‘filthy". It is heard

that families can use all their means to take revenge and can easily sacrifice their own lives to regain the lost "honor" of their families.

From the above discussions, it may be seen that

identical events, behaviors and products may evoke

diff e r e n t ideas, thoughts, feelings, emotion and images in diff e r e n t societies and thus may be associated with

di fferent types of behavior. Semiotics is a field we

shall go into because it will increase our und erstanding

on the impact of signs on culture, of semiotics because it deals with the impact of signs on culture.

1.2.4. Semio t ic s and Culture

Semi o ti c s studies how signs, or symbols operate to

make an impact in an environment. Its primary focus is on

conveying meaning. It not only deals with how reality is

co n st r u c t e d but also how it is represented. A symbol is

anything that can denote or represent something else. It

represents either tangible objects or non- tangi ble

objects. Referential symbols bring to mind the tangible

objects; w he r e a s c onnotative symbols introduce expres siv e

signs (Wilkie, 1986).

A semio ti c model puts forth three categor ies of how

products are perceived: Utilitarian, commercial and as

socio-cultural signs (Noth, 1988). Symbols come about

not directly from the product itself but f rom w hat the

producer says about the product or after the consumer

becomes s o me w ha t familiar with the product.

Produc t s in general are perceived to perform

certain functions. In reality they evoke or represent, in

an implicit or unverbal w a y , c e rt ain ideas, thoughts,

actions, feeling, emotions and images. In other words,

they create assoc i at i o n s and images in our minds with the

reality we are familiar with. Barthes (in Noth, 1988)

expla in s the process of sem a n t i zat ion of objects as

e v e n tu a l l y becoming "pervaded with meaning". He says that

"as soon as there is a society, every usage is converted

co r r e s p o n d e nc e between the perceptions of the products and the culture the individual lives in.

A consumer generally relates a particular product

to the culture he belongs to. In many cases, the consumer

may feel a certain product reflects, or relates to his

norms and values and thus may prefer to consume it as

opposed to a product which he feels is useless, silly or

unappropriate. Thus the consumer makes an associaton with

the products and his culture. Some items have

sociological signs, implying that the particular product

leads us to refer to a particular sociological group. We

can apply the same argument to cultural signs. Frequently

used examp le s are those of food, beverages, cars and

fashion products. Turkish coffee may stand for

relaxation, comfort, completion of a meal, whereas instant

coffee may stand for convenience, practical 1 ity and

studying (caffein). Certain foods may refer to certain

life-styles and cultural tastes. For example, pizza,

hamburgers and Sodas may refer to the American way of

life. Among the most successful products that have gone

global is instant coffee, hamburgers, and C o l a ’s. These

successful products are marketing in Turkey as well. What

are they compe t in g against? They are competiting with

their local counterparts, thus with Turkish tastes and

habits that reflect consumer behavior. Doner, Pide, Sis

Kebap, Ayran, Turkish Coffee and local tea reflect the

Turkish way of life.

As a conclusion, it seems that the global mark e t i n g co ncept needs to be considered in the context of

cultural differences. Treating each culture without

taking into cons i de r at i on cultural traits that lead to

certain perceptions, beliefs, images and thus different

con s um p t i o n patterns may yield many difficulties and

failures for the global products. Furthermore, treating a

p ar t icular culture or a group with certain socioeconomic, d e m o gr a p h i c or life-style chara c t eri stics as one piece of a pie would be very u n r e a listic because these certain c ha r ac t e r i s ti c s are relevant not only between cultures but

within c u l t ur e s as well. Thus, a very successful! brand

in its home country, such as Nescafe and Coca-Cola, may be very successful within only certain groups within Turkey.

II. P R ESENT RESEARCH

1 1 .1. The Purpose And The H v p othesis Of The Study

The study is based on the premise that the

m a r ke t i n g mix can not be s t a ndardized without taking into c o n si d e r a t i on factors such as the c haracteristics of the p r oduct itself, how it relates to the variety of cultures

exist i n g and to the degree of cultural sensitivity.

Food and drink are accepted to be among the most

cul t u r a l l y sensi t i v e products and thus " g l o b a l ” firms should adopt their mixes in line with the national tastes,

p r e fe rences and needs. Foreign food products are tested

with their local count e r p a r t s ( H amburgers and Doner;

C o l a ’s and Ayran; Turkish Coffee and Instant Coffee; and.

T e a - b a g s and Local Turkish tea). In Turkey, Nescafe is a

word that means "instant coffee", that is, the brand has

become the generic name for the product category. The

products in the same use categories and the same price-

ranges shall be tested. Food taste is a vital,

un i ve r s a l l y accepted habit of all societies. We are all

aware of national ca t egories of cuisines differentiated along cultural lines.

Taste is reasoned to be d ependent on intra-country

di f f e r e n t i a l s of d e m o g raphic and cultural variables.

Tastes in Turkey differ according to many variables such

as educ a t i o n and income; to demographic status such as sex

and age; to the region of origin; and finally to the

extent of expos ur e to mass media, hence to global

marke t i n g strategies.

The purpose of this survey is to explore the

possible answers to the following questions: 1) Are

global m a rk e ti n g s tr ategies useful in selling products

that have local competitors that benefit from the cultural

a c c eptance of their products through generations? 2) Do

the d i f f e r e n c e s in cultural traits of di fferent cultures

complicate, even prevent the deve lopment of global

marke t i n g strate g ie s ? Specifically, how global food and

drink produ ct s m arketing in Turkey are affected from

cultural traits such as preferences and tastes. 3) How

national differ e n ce s as well as local d ifferences

influence consumer behavior. Specifically, how

demographic, S o c i o - E c o n o mi c - S t a t us and life-style

d i ff e rences within a society lead to differ ent perceptions and c o n s u m p t i o n patterns of food and drink products.

The foll ow i n g hypothesis are p o s i t e d :

In order to posite the following hypothesis An

a s s umption has been made that firms attempting to

globalize food products are faced with co mpe tition from

local products in regard to national tastes, preferences

and habits.

1) Local c o un t e r pa r ts selected a priori are perceived to

be s u b s t i t u te s of the foreign products selected. Although

local count e r pa r ts perform different functions and are

consu m e d at different times, occassions, places and

frequenci e s .

2) The foreign products result in c ompetition with its

local co un t er p a r t because they are perceived to be

substitutes, thus both the foreign and local products must ma rk e t accordingly.

3) Within a culture different occupational groups, one

of the indicators of social status, leads to different

pe rc e p t i o n s and use frequencies of the products.

4) Within a culture, different perceptions and usage

fr e q u e n c i e s exist between the age groups, thus

generational differences are expected.

I I .2. Research Design and Methodology

I I .2.1 . Sample

The total sample consisted of 120 respondents at

Bilkent University in Ankara. Although a University

p o pulation may not be representative of the Turkish

population, a convenience sample of four different groups

(students, academic faculty, the administra tive staff and

the s u pport staff) were taken within the University. The

four groups within the total sample were selected to cover

v ariation in sub-cultures, income levels which in effect

relate to social status and life-styles. In each group,

thirty q u e stionnaires were a d m i n i s r a t e d . The groups were

broken down by the age and the sex of the participant in

order to give an insight to the effect of these variables on percep t i o ns and usage f r e q u encies of the product tested,

The first group cons i s t e d of students, a A0%

(n=12) female and 60% (n=i8) male. 97% (n=29) of the

students are in the 16-24 age bracket (see Table 1).

They may represent the new "generation" of the middle,

up p er-middle class Turkish youth. A majority of them

come from a relatively w e althy backgrounds. The second

group is the academic faculty, 53%(n=16) consisted of

women and 47%(n=14) of men. 60% (n=18) are in the 25-35

age bracket, followed by 24% (n=7) in 36-45 age bracket,

13% (n=4) over the age 45 and 3% (n=1) between 16-24(see

Table 1). They are well educa t e d and have high command

of the English language. They are the only group who have

either received a degree abroad or at least visited a

foreign country, the foreign country being the US for a

majority. Most are in their early thirties and have

com f o r t a b l e salaries. The third group is the

a d m i n i s t r a t iv e staff con s i s t i n g of 50%(n=15) men and 50%

(n=15) women. The 16-24 age bracket compose 50% (n=15) of

the a d mi n i s t r a t iv e staff, followed by 33% (n=10) 25-35 age groups, 10% (n=3) over 45 and 7% (n=2) 36-45 age group(see

Table 1). They are also educated, although at a lower

degree than the faculty. The salaries they receive are

below that of the faculty, but above that of the support

staff. Finally, the last group c o n sidered is the support

57% (n=17) consist of ages between 25-35, 23% (n=7) of

ages 16-24, 13% (n=4) and finally 7% (n=2) of ages over

45(see Table 1). They represent a lower income group, with

el e mentary school education. This group has totally

different cultural values and a d ifferent life-style than the other groups.

I I .2.2. Material

A que st i on n a i re (See Appendix A) has been

designed to assess the v ariation in consumption patterns and p e r ception of eight products tested pertaining to the d ifferent levels of sex, age and occupation.

The q u e st ionnarie was designed in a fashion that

would not offend the respondents in any respect. Food is

a product category that is consumed no matter what the

educational, cultural or income level of the respondent

and thus relates to every o n e that has filled out the

questionnaire. Thus, the respondent is capable to answer

the q uestions accurately wi t h o u t facing any di fficulties in comp r e h e n di ng what is being asked about products for

which they are well informed. The local food products

selected are Doner, Ayran, Turkish Coffee and Demli-tea.

The foreign c o unterparts selected, repectively are

Hamburgers, Coca-Cola, Nescafe and Tea-Bags. Hence, they

are products already a success in their home markets. Nescafe is a word representing instant coffee in Turkey

and is used likewise. No word exists for soda in Turkish,

thus the most popular soda in Turkey is tested. 32

The first three q u estions in the ques tio nnaire have

been asked in relation to the independent variables of

age, sex and occupation. Ques ti ons four through eight

were asked to assess the depe n d e nt variable. The fourth

question was posed so as to m e asure the frequency of use

of the eigh t food products in question. A scale of six

fr e q u e n c i e s were provided ranging from c onsuming the

product e v er y d a y to never c o nsuming it at all. The

fifth question was posed in order to measure the frequency

of use of each product by the r e s p o n d e n t s ’ parents.

This questi o n is intended to be a proxy measure whether

there is a generation gap by means of comparing the

ratings of parents and children on the consumption of

these products. The respondents were told that health

co n s i d e r a t i o n s should be brought down to a minim um level in order to prevent responses such as fatty foods are not

for elder people. It has been observe d that some of the

respondents are not c onscious of the exact rate of co n su m p t i o n by their p a r e n t s ’ and thus p redictions to some

ex t e n t prevail. Some of the r e s p o n d e n t s ’ p a r e n t s ’ no

longer live and thus have left this question unanswered. The sixth question is asked in order to get an

idea of pe r ce p ti o n s towards each of the products. It is

designed in an o p e n-ended format in order to enable the

respondent to give their own answers witho ut being

influenced or limited to a p r e - d e t e r m i ne d set of multiple

researcher an insight of how each sample perceives the p r o d u c t s .

The seventh question was also formated in an open- ended fashion in order to yield the reasons underlying the preferences for or rejections of the pa rticular products. It is crucial that the respondent comes up with his own

attributes, drawbacks etc. w i thout being influenced so

that the researcher can more o b j ec tiv ely understand the

actual reasons behind its being favored to or by other

p r o d u c t s .

Q u e s t io n number eight, the final question, was

asked in order measure w h ether the foreign products of

similar usage value are perceived to be substitutes to

their local counterparts. A pilot study has been

conducted after which question number eight was designed

in a multiple choice fashion. In the pilot survey, the

question was designed in an o p e n - e n ded fashion in which some of the respondents were unable to clearly understand

what was being asked. Thus, by providing a list of

products to choose from, as well as an " o t h e r ” option,

the exper i me n t e r could get the intended results in order to serve the purpose of the survey

I I . 2.3. Procedure

The ques t io n n a ire s were handed out individually to

each respondent. Each pa r t i c i p a n t was screened according

to their status in the Uni v e r s i t y and the surveys were

given out to add up to exactly 30 per group. Each

respondent was approached individually and his cooperation

was securred. The following day the surveys were

recollected by the researcher. Response rate was 100% for

all the groups except for the support staff whose response rate was 70%.

I I .?.4. Results

The data were analyzed with SPSS (Statistical

Package for Social Sciences) first in terms of the

overall c on s u mption frequencies of each of the eight

products (See Row Totals of Table 2), followed by the

usage f r e q uencies of parents as pe rceived by the

pa r ticipants (See Table 3). Usage frequencies were then

analyzed with regard to different levels of s ocio-economic

status in which a comparison was made by grouping

o c c u p a t i o n groups in two (See Table 4): The academic

faculty and students were collapsed to represent the

u p pe r - m i d d l e class; and, the adm i nist rat iv e staff and the

support staff represent the lower-middle class. Usage

fr e qu e n c i e s were also analyzed with regard to age (See

Table 5). Finally, an analyses of usage frequencies

between two different age groups were made in order to

m e asure the generational d i f f e rences (See Table 6). The

four age groups were not taken in order to avoid d ou ble

counting. A 45 year old p a r t i cipant in our survey may

have been compared with the 35 year old parent of an 18