Maternal emotion regulation, socio-economic status and social context as predictors of maternal emotion socialization practices

Tam metin

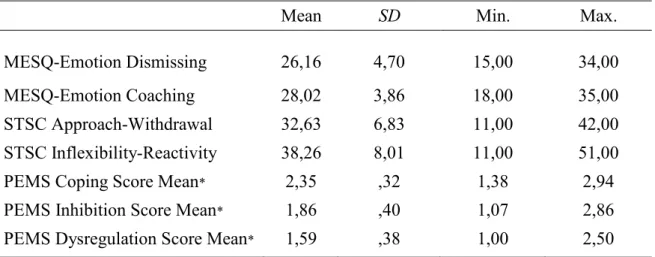

Şekil

Benzer Belgeler

In addition, in many criminal cases, the time of death, and place of death can be detected by investigating the insects around, in and on the corpse (Forensic

However, it is possible to single out typical grounds for (legislative) restriction of human and citizen rights and freedoms in most constitutions, including the

Within these slow movements, Cittaslow movement guides cities to a development model which offers sustainable regional development with local values, economic,

A reading of Layton’s poetry relating to the Jewish themes brings to light the matrix of Nihilism as was conceived by Nietzsche.. By presenting this aspect in his Jewish poems,

Araştırma- ya dahil edilen yaşlıların yaşadıkları ortamlara göre SF-36 Yaşam Kalitesi Ölçeği alt başlıkları ve Geriatrik Depresyon Ölçeği puan

Değerli okurlarımız, hastanelerde hemşirelik hizmetlerinin geliştirilmesi ve özellikle Psikiyatri hemşireliği eğitimi için yaptıkları ile Türk hemşireleri için bir

VEGF düzeyleri anlamlı şekilde yüksek bulunmuştur. Bu da sigara ve yeni kemik oluşumu arasındaki ilişkiye yardımcı olabilecektir. VEGF ile kemik döngüsünün

Bizim gibi kendinden bahsettirmek fırsatını çok az bulmuş milletlerde Cumhurbaşkanımızın Amerikayı zi yareti, ve bilhassa Washington’da Amerika me bus,