T. C.

SELÇUK ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ

YABANCI DİLLER EĞİTİMİ ANA BİLİM DALI İNGİLİZCE ÖĞRETMENLİĞİ BİLİM DALI

A STUDY ON SOME COMMON ERRORS MADE BY STUDENTS

AT SCHOOL OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES AT SELCUK

UNIVERSITY

YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ

DANIŞMAN

YRD. DOC. DR. ECE SARIGUL

HAZIRLAYAN SENGUN BAYSAL

i

ABSTRACT

This study was carried out to analyze the sources of major errors in the use of English grammatical prepositions committed by the students in foreign language learning in preparatory section at Selcuk University. After the analysis, grammatical prepositions have been studied in the classroom using communicative methods and activities.

The first chapter aims to present the background of the study as well as the problem, hypothesis, purpose and the limitations of the study.

The second chapter deals with the review of the literature about error analysis and the explanation of causes of errors by giving examples.

In the third chapter, the information related to experimental study is given. The method, materials and data collection procedure have been presented here.

The forth chapter is devoted to data analysis and interpretation of the tests. Also, the results of the study have been given through the interpretation of tables.

The fifth chapter concludes the study with some recommendations .It also includes some related appendices.

ii ÖZET

Bu çalışmanın amacı, Selçuk Üniversitesi Hazırlık sınıfı öğrencilerinin İngilizce’deki ilgeçlerin kullanımında yaptıkları temel hataları ve bu hatalara neden olan faktörleri incelemektir. Bu analizden sonra ilgeçler, iletişimsel aktivitelerle sınıfta yeniden çalışılmıştır.

Çalışmanın birinci bölümünde, çalışmanın zemini ve problemin sunumu, çalışmanın hipotezleri, amacı ve çalışmada kullanılan sınırlılıklar belirtilmiştir.

Çalışmanın ikinci bölümü literatür taramasını içerir. Hata çözümlemesi ile hataların sebepleri detaylı olarak örneklemelerle gösterilir.

Üçüncü bölüm, deneysel çalışma ile ilgili detaylı bilgileri içermektedir. Metot, materyaller ve veri toplama işlemi bu bölümde sunulmaktadır.

Dördüncü bölümde veri analizi ve deneysel çalışmanın yorumlanması bulunmaktadır. Çalışma sonuçları tablolar halinde de verilmektedir.

Sonuç bölümünde ise çalışmanın bulguları yorumlanmakta ve öneriler sunulmaktadır. Tezin bitiminde ise bu çalışma ile ilgili ekler yer almaktadır.

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost I would like to express an immense gratitude to my supervisor Assist. Prof. Dr. Ece Sarıgul for her support, guidance, and patience throughout my research study. I could have never achieved this without her encouragement.

I am also very grateful to all my teachers at the ELT Department of Faculty of Education, Selcuk University for their valuable support and comments.

I wish to thank to Assist. Prof. Dr. Ali Murat Sunbul and my colleague Erkam Isık for their invaluable help with the statistical analysis.

I am deeply thankful to my colleagues, especially who helped me during my study for their cooperation and friendship.

I am very grateful to my family and especially to my husband, Tamer and my dear son , Alper for their support, help and patience and my little daughter, Elif, who tried to be patient enough during my study.

I owe special thanks to my colleague Zeynep Ortapisirici for her moral support and valuable suggestions for my study.

Finally, I also wish to express my gratitude and special thanks to my family who shared the difficulties in this study and life.

iv ABSTRACT ÖZET ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Page

1.1. Presentation ……… 1

1. 2. Background of the Study………... 1

1. 3. Problem………...2

1. 4. Purpose of the Study and Research Hypotheses………..3

1. 5. Limitations of the Study………..4

CHAPTER II REVIEW OF LITERATURE 2. 0. Presentation………. 6

2. 1. What is Contrastive Analysis? ………....8

2. 2. Error Analysis……….10

2. 3. The Process of Error Analysis………12

2. 3.1.Identifying Errors……….12 2.3.2. Describing Errors……….13 2. 3.3. Evaluation of Errors………14 2. 3. 4. Causes of Errors………..15 2.3. 4.1. Interlingual Errors………15 2.3. 4. 2. Intralingual Errors………...23 2. 3. 4. 3. Other Possible Causes………26

v

CHAPTER III METHODOLOGY

3. 1. Introduction……… 31

3. 2. Research Design……….31

3. 3. Subjects……….. 33

3. 4.Materials………. 33

3. 5. Data Collection Procedure………. 35

3.5.1. The Experimental Group………..36

3.5.2. The Control Group………... 38

CHAPTER IV DATA ANALYSIS 4. 1. Introduction……… 39

4. 2. Data Analysis Procedure……… 40

4. 3. Results of the study……… 41

4. 3. 1. Pre-test……….. 41

4.3.2. Post-test……… 42

4.3. 3. Retention test (Delayed post –test)………..44

4.4. Lesson Diary after the Study……… 47

CHAPTER V CONCLUSION 5. 1. Introduction………50

5. 2. Results……….... 50

5. 3. Conclusion and Recommendations………52

BIBLIOGRAPHY APPENDICES

vi

List of Abbreviations

CA Contrastive Analysis

CAH Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis

EA Error Analysis

SLA Second Language Acquisition

NL Native Language

TL Target Language

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

1. 1. Presentation

This chapter begins with background of the study. The purpose and hypotheses of the study follow the problem statement. The next part is devoted to the limitations of the study. 1. 2. Background of the Study

The teaching of grammar has always played an important role in foreign language teaching. Actually for centuries the only activity of language classrooms was the study of grammar. Many student errors in speech and writing performance are considered grammatical.

If we go into a classroom where students are learning a foreign language, if we listen to them speaking that language or look at what they have written, we notice that the same mistakes of pronunciation, spelling, grammar and vocabulary tend to occur. Almost all these errors occur because of the mother tongue interference. An approach on this field, usually called Contrastive Analysis (CA) has grown up and become a major point for linguists to study. Also for many curriculum specialists, the Contrastive Hypothesis (CAH) provided an important guide to the selection and sequencing of items for instruction. According to David Nunan (1991:144), this hypothesis claims that a learner’s first language will have an important influence on the acquisition of a second. It is assumed that where first language rules conflict with second language rules, errors reflecting the first language will occur as learners try to use the second language – in other words, the first language will ‘interfere ‘ with the second.

2

H. Douglas Brown (1994: 206) explains that learners do make errors and that these errors can be observed, analyzed, and classified to reveal something of the system operating within the learner, leads to a surge of study of learners’ errors, called error analysis Error analysis becomes distinguished from contrastive analysis by its examination of errors attributable to all possible sources, not just those which result from negative transfer of the native language. Errors arise from several possible general sources: interlingual errors of interference from the native language, intralingual errors within the target language and some other possible causes such as carelessness or other errors encouraged by teaching such as hypercorrection and faulty rules given by the teacher.

Studying on errors is an interesting area of second language teaching. The nature of a mistake or error is more interesting than the fact that a mistake has been made. They can provide one of the most valuable materials for a class to work. Your attitude towards errors is important, too. Starting from mistakes means starting from where your learners are and therefore; it can give a clue to how teachers can help to move to the next stage.

1. 3. Problem

The difficulties of teaching prepositions to Turkish students learning English have been observed for a long time by language teachers. The role of the interference i.e. effects of the native language has been stressed for a long time in second language teaching. Mother tongue interference, which is also called negative transfer, is surely one of the most important sources of error among second language learners. Because of the negative transfer of Turkish prepositional knowledge to English, the students have difficulties in producing correct English forms of prepositions. For example:

My mother was angry to me. She hates from horror films.

3 She listens(…) music in her spare time.

As English teachers, we have some questions in our minds:

Why do students make errors in prepositions? What kind of errors do they make? Why are some of the errors the same? What kind of communicative activities can be used to teach English prepositions in grammar communicatively and how can we emphasize and make our colleagues aware of the importance of the interference in explaining the causes of students’ errors?

1. 4. Purpose of the Study and Research Hypothesis

Prepositions are difficult to use in any language. However, the situation is made more difficult by Mother Tongue Interference. The aim of this study is to investigate the origins of errors produced by Turkish learners of English and what sort of difficulties students meet during their mastery of English. In this study, the errors made in the use of prepositions are explored and the reasons are explained.On the basis of these errors,this study also aims at determining if communicative activities are effective in terms of improving students’ prepositional knowledge in grammar.

Prepositions can be considered as function words in this study.In order to teach these words, vocabulary teaching methods have been revised. Two vocabulary teaching methods have been used: Meaning-inferred method through communicative activities and meaning-given method. Therefore, it examines the difference between a group of students taught prepositions in context through communicative activities using dialogues and role plays effectively and another group taught prepositions in lists through a meaning-given method. In addition, a second purpose was to investigate if teaching grammar in context through communicative activities makes preposition teaching more memorable.

4

Accordingly, this research tested the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis : Difficulties with prepositions because of Mother Tongue Interference have been observed for some time by the researcher. The researcher predicts that the students whose teachers use communicative activities such as dialogues and role plays and teach the prepositions in context will score significantly higher on the post-test than the students whose teachers use lists for teaching prepositions and give the meanings. The researcher also predicts that the students whose teachers use communicative activities will score significantly higher on the retention test than the students whose teachers use list of prepositions in the meaning-given method.

1. 5. Limitations of the Study

This study is limited by several conditions:

1) This study is conducted on early pre-intermediate level young adult students at Selcuk University, School of Foreign Languages. The groups were chosen according to their scores in the Placement Test at the beginning of the first semester. After nearly five months, the students’ language levels might have varied. This variation may have affects on the measure. 2) The other limitation of the study is the number of the students in experimental and control groups. The number of the subjects in the experimental group and control group was both eighteen. So, in this study the total number of the subjects was thirty-six. Due to small number of subjects involved in the research, the results will be limited to the subjects under study. A larger group of subjects would help to produce results that are more reliable.

3. The second limitation is the educational backgrounds of the groups. Although the students were from the same faculties, that is to say, they were the students of the Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Faculty of Engineering and Faculty of Technical Education, and their proficiency averages were more or less the same, there

5

were some inequalities in their educational backgrounds concerning the courses they had in high school.

4. Another limitation is the period of the study. The curriculum was intense and we as the instructors had to finish the weekly plan. Thus, the study took four hours a week and it lasted four weeks.

5.We have analyzed some of the errors that students have made due to the mother tongue interference or negative transfer in this study (interlingual errors).Not all errors have been included.

6 CHAPTER II LITERATURE REVIEW 2. 0. Presentation

Learning a language is a complex process and during this process learners meet some difficulties and consequently they often commit errors. Until recently, theorists and methodologists discussed who should be accepted responsible. Some of them regarded students as completely responsible for errors, and others the teacher, depending on their standpoint. On the one hand, teachers are blamed for causing errors by careless planning or teaching, on the other hand students are accused of their lack of motivation, self-discipline or general intelligence. We should accept that there is truth on either side. However, it is obvious that even the most motivated and most intelligent students who perform well in controlled practices make errors.

According to generally accepted belief now errors are not evidence of failure to learn; they are rather evidence of learning that takes place. According to Gerry Abbott and Peter Wingard (1981:214), there are two main purposes in studying your students’ errors:

( i ) in order to get the most relevant help you can to your present groups of students; ( ii) in order to plan programmes for future groups.

Raja T. Nasr (1980:118) explains that an error analysis determines the actual problems that learners face in learning the target language. While other comparative linguistic analyses tell us in advance what theoretical problems learners will face, an error analysis tells us really what mistakes they actually do make. This type of analysis is of great help to teachers; it tells them what new or additional materials and methods they need to use to solve the real problems of the learners.

7

To begin with, it is necessary to make a distinction between errors and mistakes to analyze learner language better. Errors illustrate gaps in a learner’s knowledge; they occur because learner does not know what is correct. Mistakes reflect occasional lapses in performance; they occur because the learner is not able to perform what he or she knows.

The following example is from a written homework of a student. It is an example of a ‘mistake’. At the beginning of his composition he says:

Then I cleaned my teeth and washed my hands; using the past tense of the verb ‘wash’ correctly. However, in the last sentence he says:

I wash my face last night and, then went to bed.

Making what seems to be a past tense error. But clearly he knows what the past tense of ‘wash’ is as he has already used it correctly once. His failure to say ‘washed’ in the last sentence might be considered a mistake.

How can we distinguish errors and mistakes? According to Rod Ellis (1997: 17) the answer for this question may be to check the consistency of learner’s performance. If the student above consistently substitutes ‘wash’ for ‘washed’ this would indicate a lack of knowledge- an error. However, if they sometimes say ‘wash’ and sometimes ‘washed ‘, this would show that they possess knowledge of the correct form and it is a ‘mistake’. Errors are to a large extent, systematic and to a certain extent, predictable.

Another way of distinguishing errors and mistakes is that you ask the learners to try to correct their own deviant utterances. If they are unable to, the deviations are errors. If they are successful, they are mistakes. However, it may not always be easy to make a clear distinction between an error and mistake. Learners may consistently use a feature like past tense in some contexts and consistently fail to use it in others. So it is not simple to do this and a clear distinction between an error and a mistake may not be possible. In this study, both of the terms have been used interchangeably.

8

Two significant approaches have been applied in the analysis of the difficulties encountered by second language learners and errors. General schemes of Contrastive Analysis and Error Analysis have been given below.

Before we look into the roots and development of error analysis, let us first have a look at contrastive analysis so as to understand better how error analysis became more popular among Second Language Acqusition (SLA) researchers.

2.1. What is Contrastive Analysis?

In the middle part of twentieth century, one of the most popular subjects for applied linguistics was the study of two languages in contrast. In his book Principles of language Learning and Teaching (1994: 193), Brown states that since 1940’s; Contrastive Analysis has been used to show the synchronic differences and similarities between the mother tongue and the language being learned. Contrastive analysis was developed and practiced in 1950’s and 1960’s, as an application of structural linguistics to language teaching; it has proved to be one of the most important studies ever made in describing systems of languages.

This approach takes its roots from behavioristic and structralist approaches of the day. “The Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis claimed that the principal barrier to second language acquisition is the interference of the first language system with the second language system, and that a scientific, structural analysis of the two languages would produce a taxonomy of linguistic contrasts between them which in turn would enable the linguist to predict the difficulties a learner would encounter.

According to Richards (1985: 63), Contrastive Analysis is based on the following assumptions:

a) The main difficulties in learning a new language are caused by interference from the first language.

b) These difficulties can be predicted by Contrastive Analysis.

9

Randal Whitman (1970:193) noted that Contrastive analysis involved four different procedures :

The first of these is description: the linguist or language teacher, using the tools of formal grammar, explicitly describes the two languages in question. Second, a selection is made of certain forms – linguistic items, rules, structures – for contrast, since it is impossible to contrast every possible facet of two languages. The third procedure is the contrast itself, the mapping of one linguistic item onto the other, and a specification of the relationship of one system to the other. Finally, one formulates a prediction of error or difficulty on the basis of the first three procedures.

While discussing contrastive analysis, Ronald Wardhaugh (1970:193) suggested that we should distinguish a ‘strong claim ‘from ‘a weak claim’. The strong claim is that contrastive analysis can reliably predict difficulty and errors but this claim has not been supported by the evidence. Teachers have found that some of the errors predicted by contrastive analysis have often not occurred, whereas many actual errors would not have been predicted. The weak claim is, however, generally considered to be more acceptable. This is that, after we have observed what errors learners actually make, contrastive analysis can help to explain some of these errors, namely, those which are due to transfer. In this capacity, contrastive analysis becomes part of the wider undertaking of error analysis.

According to CA, it seemed reasonable to suppose that wherever the structures of the mother tongue and target language differed there would be problems in learning and difficulty in performance, and the greater the differences were, the greater the difficulties would be. Thus CA sets out to predict where errors are likely to occur and indicate likely problem areas on which teaching should be focused.

CA was found to work well on phonological level but its failure to predict all the errors made in other areas led to a growing interest in error analysis, which starts with errors and then tries to find out their causes.

10 2.2.... Error Analysis

The study of errors is carried out by means of Error Analysis (EA).In the 1970s ,EA took the place of Contrastive Analysis (CA),which predicts the errors that learners make by identifying the linguistic differences between their first language and the target language. The underlying assumption of CA was that errors occurred primarily as a result of interference when the learner transferred native language habits into the target language. Interference was believed to take place whenever the habits of the native language differed from those of the target language.

CA gave way to EA .CA looked at only the learner’s native language and the target language. EA provided a methodology for investigating learner language. For this reason, EA constitutes a starting point for the study of learner language .

Rod Ellis (1997: 15) states that although it may seem rather odd to focus on what learners get wrong rather than what they get right, there are good reasons for focusing on errors. First, they are a conspicuous feature of language, raising the important question of why do learners make errors? Second, it is useful for teachers to know what errors learners make. Third, it is possible that making errors may actually help learners to learn when they self-correct the errors they make.

Before 1960s, when the behaviouristic viewpoint of language learning appeared, learner errors were considered something undesirable and to be avoided. It is because in behaviourists’ perspectives, people learn by responding to external stimuli and receiving proper reinforcement. A proper habit is being formed by reinforcement, and then learning takes place. Therefore, errors were considered to be a wrong response to the stimulus, which should be corrected immediately after they were made. Unless corrected properly, the error became a habit and a wrong behavioral pattern would stick in your mind.

11

This viewpoint of learning influenced greatly the language classroom, where teachers concentrated on the mimicry and memorization of target forms and tried to introduce the correct patterns of the form into learners' mind gradually. If learners made any mistake while repeating words, phrases or sentences, the teacher corrected their mistakes immediately. Errors were regarded as something you should avoid and making an error was considered to be fatal to proper language learning processes.

Brown (1994: 206) says about error analysis;

“ The fact that learners do make errors and that these errors can be observed, analyzed, and classified to reveal something of the system operating within the learner, led to a surge of study of learner’s errors, called Error Analysis ”.

It is to S.P. Corder that Error Analysis owes its place as a scientific method in linguistics. As Rod Ellis cites (p. 48), "it was not until the 1970s that EA became a recognized part of applied linguistics, a development that owed much to the work of Corder". Before Corder, linguists observed learners' errors, divided them into categories, tried to see which ones were common and which were not, but not much attention was drawn to their role in second language acquisition. It was Corder who showed to whom information about errors would be helpful (teachers, researchers, and students) and how.

According to Brown(1994), Error Analysis distinguishes from contrastive analysis by its examination of errors attributable to all possible sources, not just those which result from negative transfer of the native language. Error analysis easily superseded contrastive analysis, as it has been discovered that only some of the errors a learner makes are attributable to the mother tongue. The learners do not actually make all the errors that contrastive analysis predicted they should. The learners from different language backgrounds tend to make similar errors in learning one target language. Errors arise from several possible general sources:

12

Interlingual errors of interference from the native language, intralingual errors within the target language and some other possible causes such as carelessness or errors encouraged by teaching such as hypercorrection and faulty rules given by the teacher.

2.3. The Process of Error Analysis

Errors are studied in order to find out something about the learning process and learning strategies. By studying examples of language produced by foreign language learner, the teachers can discover what he thinks the rules of the foreign language are. The teachers have to be careful in examining students’ errors. Let’s consider the steps in detail.

2.3.1. Identifying Errors

The first step in analyzing learner errors is to identify them. To identify errors we need to compare the sentences learners produce in what seem to be normal or correct sentences in the target language. Most of the time, it is not difficult to do this. Most teachers often have developed senses of error detection because they know that their students are likely to do these particular mistakes. For example:

My father and my mother was coming home……

It is not difficult to see that the correct sentence should be: My father and my mother were coming home……

When we compare these two sentences, we can see that the student has used ‘was’ instead of ‘were’ - an error of subject-verb agreement. Sometimes however, it is difficult to reconstruct the correct sentence because we are not sure what the student meant. Douglas Mc Keating (1981:218) gives the following example:

I used to clean my teeth every night before I go to bed.

If you look at an error in context, identifying it depends on interpretation, i.e. what you know the student meant. Therefore, linguistic context often helps the teacher to determine

13

whether an error has been made or not. If the context suggests that the student is talking about the present, we may interpret that ‘used to’ is probably wrong; but if the context suggests the past simple tense, then go is probably wrong. Context is very important in identifying errors and identifying the exact errors that the learners make is often difficult.

Clues for interpretation may be available from these factors: a. general context b. a knowledge of similar errors made by similar students c. a knowledge of the students’ mother tongue and the possible results of phonological interference or of direct translation into English d. direct questioning, perhaps in the mother tongue, as to what the student meant.

2.3.2. Describing Errors

After the errors have been identified, they can be described and classified. One way is to classify errors into grammatical categories.

Mc Keating (1981:223) classifies those errors superficially in this way and gives the following examples:

omission e.g. Cow is a useful animal. addition e.g. She came on last Monday. substitution e.g. He was angry on me.

mis-ordering e.g. He asked her what time was it.

He also remarks that this classification is not sufficient; to start with we need to know what was omitted, added, etc. And later we will put the items into more general classes: prepositions, tense forms, questions, etc.

Mc Keating ( 1981:223) claims in his article that some people omit the stage of this linguistic classification and classify errors immediately in their terms of their assumed causes such as errors of hypercorrection, false analogy and so on. However, in any analysis an

14

explanation of causes of errors is speculative part of the whole process; we surely need a grammatical classification for practical purposes, for example remedial teaching or syllabus planning.

2.3.3. Evaluation of Errors

We need to evaluate errors because the purpose of the error analysis is to help learners learn an L2. Some errors can be considered more serious than others because they are likely to interfere with the intelligibility of what someone says. These errors are called ‘global errors’. These kinds of errors hinder communication and they prevent the hearer from comprehending the message. Teachers will want to focus on these errors.

His like a friend to find now is very difficult.

( It is very difficult to find a good friend like him now.)

Other errors, known as local errors, affect only a single constituent in the sentence (for example the verb) and are perhaps, less likely to create any processing problems. Local errors don’t prevent a hearer from getting the message because there is only a minor violation of one segment of a sentence. So the hearer can make an accurate guess about the intended meaning .For example:

When talk finish, --- I talk with they.

I study one hours a day.

15

Global errors affect overall sentence organization. Examples are word order, missing or wrongly placed sentence connectors, and syntactic overgeneralizations.

Local errors are the ones that affect single elements in a sentence. For example, errors in morphology or grammatical functions like articles, tenses and pluralisation.

How can teachers be guided about what kind of errors they should pay attention to? The general conclusion about this subject is that teachers should pay attention very carefully to errors that interfere with communication. So priority in error correction should be given to global errors in order to develop students’ communicative skills.

2. 3.4. Causes of Errors

How can we determine the source of an error? Why are certain errors made? What cognitive strategies underlie certain errors? It is not always easy to give answers to these questions, and the value of interlingual analysis comes out in such questions. There is much to be gained from a consideration of the possible causes of errors and teachers should bear this in mind and be prepared to consider alternative explanations.

2.3.4.1. Interlingual Errors

Before the SLA field ,as we know it today, was established, from the 1940s to the 1960s, contrastive analyses were carried out, in which two languages were systematically compared. Researchers at that time were motivated because they were able to identify points of similarity and difference between native languages (NLs) and target languages (TLs). There was a strong belief that a more effective pedagogy would result when these were taken into consideration. Charles Fries, one of the leading applied linguists of the day, said: "The most efficient materials are those that are based upon a scientific description of the language to be learned, carefully compared with a parallel description of the native language of the learner."(Fries 1945: 9)

16

Robert Lado, Fries' colleague at the University of Michigan, also expressed the importance of contrastive analysis in language teaching material design:

Individuals tend to transfer the forms and meanings and the distribution of forms and meanings of their native language and culture to the foreign language and culture - both productively when attempting to speak the language and to act in the culture and receptively when attempting to grasp and understand the language and the culture as practiced by natives. (Lado 1957, in Larsen-Freeman & Long 1991:52-53)

This claim is still quite interesting to anyone who has attempted to learn or teach a foreign language. We encounter so many examples of the interfering effects of our NLs.

This conviction that linguistic differences could be used to predict learning difficulty produced the notion of the contrastive analysis hypothesis (CAH): "Where two languages were similar, positive transfer would occur; where they were different, negative transfer, or interference, would result." (Larsen-Freeman & Long 1991: 53)

The procedure of mother tongue interference can be schematized as follows:

Sarıgul (1999: 125) Interference

Positive Negative

In the mother tongue In the target language

When first language habits are helpful to acquiring second language habits, this is the

positive transfer. For example some vocabulary items and structures of English are similar in form and meaning to Turkish:

17 English Turkish

film film sandwich sandviç star star

She is a secretary. O bir sekreterdir. He understands me. O beni anlıyor.

Finding similarities like those between native language and target language is an advantage in language teaching.

On the other hand; negative transfer occurs in the areas where the native language and foreign language differ clearly. The first language habit now hinders the learner in learning the new one. For example:

English Turkish artist artist apartment daire

He went to İstanbul with train. İstanbul’a trenle gitti. She died two months before. İki ay önce öldü. He went to holiday last month. Geçen ay tatile çıktı.

This is the negative transfer, or in the most common terminology, interference. In this way, differences between the two languages lead to interference, which is the cause of learning difficulties and errors.

18

Then, second language learning requires overcoming the differences between the first and second language systems. Robert Lado summarized the learner’s problem as follows: "Those elements that are similar to his native language will be simple for him, and those elements that are different will be difficult" (Lado 1957: 2). This has strong effects for second language teaching:

1. We can compare the learner’s first language with the second language he is trying to learn (an activity which is usually called ‘contrastive analysis ‘)

2. From the differences that emerge from this analysis, we can predict the language items that will cause difficulty and the errors that the learner will be a prone to make (a belief which is usually called the ’contrastive analysis hypothesis‘).

3. We can use these predictions in deciding which items need to be given special treatment in the courses that we teach or the materials that we write.

4. For these items in particular, we can use intensive techniques such as repetition or drills, in order to overcome the interference and establish the necessary new habits (such techniques forming the basis of so-called ‘audio-lingual’ or ‘audio –visual’ courses.

According to Gerry Abbott and Peter Wingard (1981:239), the elimination of many errors requires teaching that is concentrated and regularly revised. It is of little value merely to correct fifteen different errors in a piece of written work or write up on the board corrected versions of twenty or thirty different errors made by the whole class and then to assume that you have done the remedial work for the week and that the students will not repeat the mistakes. Such activities partly fulfill one of the requirements of remedial work: those learners should be aware of their errors; but they are unlikely to affect their future performance. This is because there are so many topics to deal with in one session and you can’t focus enough attention on any of them and with so many isolated problem areas to think

19

about in quick succession, students are likely to remember only a few of them in any case. It is more efficient, therefore, to select a few errors yourself and really concentrate on them.

In this study, the researcher has chosen prepositional errors that students frequently made to focus on. She selected some common prepositional errors for this study. The students had problems especially with prepositions after verbs and adjectives. Why is it difficult to learn prepositions in grammar? What is a preposition? In Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (2003:1290), a preposition is described as a word that is used before a noun, pronoun, or gerund to show place, time, direction etc.

Prepositions are words normally placed before nouns or pronouns. (A.J.Thomson, A.V.Martinet, 1986:91). According to him, the student has two main problems with prepositions. He has to know:

a) whether in any construction a preposition is required or not b) which preposition to use when one is required.

As Haycraft (1978: 25) noted prepositions are difficult to use in any language and the situation is made more difficult by mother tongue interference. The case is the same with our students, too.

The researcher collected the data for this analysis from the students’ weekly writing tasks (projects), examination scripts and utterances they have made in speaking exams. They are all the original ones.

Here are the interlanguage errors made by Turkish students at SOFL that form the base of this research:

20 1. He hates from horror films

2. I failed from the second exam. 3. If I pass from the final exam, ……

4. The bus leaves from the station at 9 o’clock. 5. I’m bored from the lessons.

6. He’s frightened from dogs. 7. My father is proud from me. 8. I’m tired from English exams. 9. My little sister is afraid from dark. 10. I’m responsible from tidying my room. 11. The teacher complained from him. 12. She doesn’t like going to home early. 13. I phone to my mother everyday.

14. My hobbies are listening(…) music, reading books and traveling. 15. When his father looked to him, ……

16. She smiled to me.

17. My friends laughed to my jokes. 18. I agree to him.

19. My father was angry to me. 20. We went to a meal.

21. I’m going to apply to a job after I graduate from the university. 22. The teacher wrote the keywords to the whiteboard.

23. I spend all my money to clothes and shoes. 24. I met with my boyfriend at university. 25. I want to marry with her.

21 26. My father helped my homework.

27. I’m interested with football. 28. I’m going to talk with her.

29. I’m excited for the Beşiktaş match. 30. My mother worries for me.

31. I want to apologize about my behaviour. 32. I want to work at a computer company.

In the first four examples, we can see that preposition from is used unnecessarily in English due to mother tongue interference. In 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11 students have used this preposition (from) instead of with, of, for or about.

Another problematic preposition is to. In 12 and 13, students added this preposition unnecessarily. In 12, ’to’ is used to say where she goes but in English, we don’t have a preposition in this expression. We say ‘go home’. In 13th example, Turkish students use ‘phone to someone or to a number’ but in English grammar phone is followed immediately after a noun. In 14, because in Turkish we don’t have a preposition after this verb (müzik dinlemek) they omitted the preposition though it was necessary. In the examples in 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and 23 to is used in place of at, with, for or on in a wrong way.

The third problematic preposition was with. In 24 and 25, the preposition with is used in the sentence although it is not necessary. It is clear that students think in Turkish and try to make sentences in English without considering the grammar of English. In 24, with is often used with this verb(meet) by Turkish students.In Turkish grammar,we need this preposition here but in English meet means seeing and talking to someone for the first time,or being introduced to them and no preposition is needed.

Onunla evlenmek istiyorum. I want to marry with her.

22

In 25, ‘marry’ is that if you marry someone, you become their husband or wife and no preposition is used but in spoken English; ‘get married’ is more common than ‘marry’. So we can say ‘get married to someone’ or ‘be married to someone’ but not be married with or get married with. In 26, students omitted the preposition with when it was necessary. In 27 and 28 students used this preposition wrongly instead of in and to. In 29 and 30 we see that students used for preposition in place of about just because they have tried to use their mother tongue grammar rules (Turkish) without thinking which preposition should be used after adjectives and verbs in English.

The same problem occurs in 31 and 32 again. Students used the prepositions improperly. In 31 and 32, the preposition about and at are used in place of for.

Wilkins in Linguistics in Language Teaching (1972:197) states:

The errors and difficulties that occur in our learning and use of a foreign language are caused by the interference of our mother tongue. Wherever the structure of the foreign language differs from that of the mother tongue we can expect both difficulty in learning and error in performance. Learning a foreign language is essentially learning to overcome these difficulties. Where the structures of the two languages are the same, no difficulty is anticipated and teaching is not necessary. So teaching will be directed at those points where there are structural differences. The bigger the differences between the languages, the greater the difficulties will be. If a comparative study –a contrastive analysis –of the target language and the mother tongue is carried out, the differences between the languages can be discovered and thus it becomes possible to predict the difficulties that the learners will have. This determines what the learners have to learn and what the teacher has to teach. The results of the contrastive analysis are built into language teaching materials, syllabuses, tests and research.

After all these examples, it seems likely that a great many errors are caused by Mother Tongue Interference; this is certainly where most teachers would look first for an explanation and Contrastive Analysis may help us with probable trouble spots but we should also be aware of its limitations because there are also many errors which cannot be explained in this way and Error Analysis deals with them in detail. I would like to consider those ones now.

23 2.3.4.2. Intralingual Errors

One of the major contributions of error analysis was its recognition of sources of error that go beyond interlingual errors in learning a foreign language. It is now clear that intralingual transfer (within the target language itself) is an important factor in second language learning. The intralingual errors are those originated within the original structure of English itself. Researchers have found that interlingual transfer or interference is dominant in the early stages of language learning but when the learners begin to acquire parts of the new system, more intralingual transfer –generalization within the target language-occurs. As learners progress in the second language, their previous experience and their existing subsumers begin to include structures within the target language itself. When the complexity of English structure encourages such learning problems, all learners, regardless of background knowledge tend to commit similar errors. It refers to items produced by the learner that reflect not the structure of the mother tongue but generalizations based on partial exposure to the target language.

1. Cross-Association

Cross-association may be quite spontaneous and accidental but for teachers, it is very easy to encourage it by methods of presentation and practice. For example, presenting items with similar meaning but different structures together, or presenting them by way of transforms can easily cause to hybrid structures. The following way of presenting too+ adj + to + verb is very common:

This milk is very hot .I can’t drink it. This desk is very heavy. I can’t lift it. We can join these sentences like this: This milk is too hot to drink.

24 Now change these sentences in the same way: This apple is very sour .I can’t eat it.

It is not surprising that some students will produce sentences like:

This apple is very sour to eat. This apple is too sour to eat it.

Cross-association involves the transfer of some element of form and/or meaning from one member of a pair to the other, when two members are considered to be similar. If the two units of language that are sufficiently similar in form have an element of meaning in common, the units will remain closely associated in the memory. When an attempt is made to recall one of them, either

i. the wrong one is selected. ii. elements of both are selected.

That’s why students have produced such kind of errors. This apple is very sour to eat.

This apple is too sour to eat it.

Later, so + adj + that may be introduced by a similar method: For example: The apple is too sour to eat.

We can say: The apple is so sour that I can’t eat it. Now, change these sentences in the same way: The bag is too heavy to carry.

25 2. Word analogy and overgeneralization

The learner looks for patterns and regularity in the target language in an effort to reduce the learning load by formulating rules. But, he may overgeneralise his rules and fail to take exceptions into account because his exposure to the language is limited and he has insufficient data from which he can derive more complex rules .For example:

She explained me how---

This may be because of the sentences like: She showed / told me how---

which contain verbs that the learner has met and used before he encounters the exceptional explain.

Another reason for this may be that having found a rule that appears to work well the learner doesn’t need to go looking for exceptions and they think these exceptions will only complicate matters .Or, as it is simple ,he may just ignore counter- examples to his rules. It has the effect of simplifying or regularizing the language.

Now, let’s have a look at some intralingual errors that our students made: 1. He goed to the supermarket.

2. I eated pizza for lunch. 3. I buyed a new shirt. 4. My father flied to Ankara. 5. My brother has got big foots. 6. Peoples are……..

7. Mans are…….. 8. She live in Karaman. 9. I hope she like it in future. 10. He send a postcard………

26 11. Roberta believe that……..

12. My mother cook eggs for breakfast. 13. When he finish High School, …………. 14. Everybody know Ölüdeniz.

15. I don’t know what time is it.

16. He told me where should I get off the bus. 17. You can learn how is this illness cured. 18. Technology is developing very fastly. 19. Teenagers are nervously because of alcohol.

In second language acquisition, generalization has been a common process. We observe that our students, at a particular stage of learning English, overgeneralise regular past tense endings ( opened ) as applicable to all past tense forms ( goed, eated, buyed flied ) in 1, 2, 3 and 4 until they learn and recognize a set of verbs that belong in an irregular category. A reason for overgeneralising may be that when they have found a rule that work well the learner is not inclined to go looking for exceptions as they will only complicate matters. We can also give 5, 6 and 7 as other examples to prove that claim.

According to Douglas Mc Keating,(1981:232) some writers suggest that this strategy of ignoring exceptions in the interests of simplification may account for the common omission of the third person singular, present tense-s as in 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14.

In English as a second language, indirect discourse requires normal word order, not a question word order, after the wh- word. Unaware of that rule, students overgeneralise as in 15, 16 and 17.

27

In 18, 19 again the students fail to take exceptions into account Students have made this mistake of confusing parts of speech because of not having mastered the rules in the target language .

2.3.4.3. Other Possible Causes: A - Carelessness

Several writers on EA point out that we should distinguish between errors and lapses. Errors result from the learner following the rules, which he believes, are correct but which are actually wrong or inadequate in some way. The learner may find it difficult or impossible to correct an error of this type because he is following the only rule he believes. Lapses (careless mistakes) result from to follow a known rule, usually because of haste or forgetfulness. When his attention is taken to that mistake the learner usually remembers the rule and he can correct it. This is in fact something of an oversimplification and should not be pressed too far.

B. Other Errors that Teaching Encouraged: a. Hypercorrection

This sometimes results from overemphasis on items that CA indicates may present difficulty or EA indicates do present difficulty. This gives learner a false impression of the importance of the item and they are so worried about not using them correctly that they overuse them. Over emphasis on 3rd person is a common example for this:

I goes to the cinema with my friends or parents at the weekends. My friends comes to my house.

28 b. Faulty rules that the teachers gave:

Teachers sometimes give students rules that are not adequate and when students follow them they make errors similar to those caused by the overgeneralisation of their own rules.

For example:

‘If the action is in the past, the verb must be in the past tense.’ It results in a form of hypercorrection and errors appear:

Last night, he wanted to played football but his father told him he had to finished his homework.

I saw him closed the window.

2.4. Error Correction

Recently, the focus of classroom instruction has moved from the emphasis on grammar to attention to functional language within communicative contexts. Therefore, the question of the place of error correction has become very important.

In Brown’s Principles of language learning and teaching((1987:194) it is advised by Hendrickson to try to see and notice the difference between global and local errors. Brown gives the following example for this:

Once, a learner of English was describing an a quaint old hotel in Europe and said:

‘There is a French widow in every bedroom.’ The local error is clearly and humorously recognized .Instead of window, he said ‘widow’. Hendrickson recommends that local errors usually need not be corrected because the message is clear and correction might interrupt the learner’s productive communication.

29

On the other hand, he recommends that global errors need to be corrected in some way because the message may otherwise remain unclear and difficult to understand. ‘I saw their department’ is a sentence that needs to be corrected if the hearer is confused about the final word in the sentence.

Some utterances are not clearly global or local and it is difficult to decide about the necessity for corrective feedback. The final words about it are that a teacher must not stop the continuation of students’ attempts at production by covering them with much corrective feedback.

Brown (1994:221) explains that the matter of how to correct errors is getting quite complex. Researches on error correction methods do not conclude about the most effective method for error correction. It seems quite clear that students in classroom want and expect errors to be corrected (Cathcart and Olsen 1976) and it is the teacher’s task to balance various perspectives. In Vigil and Oller’s model (in Brown 1994) for a theory of error correction , cognitive feedback must be optimal in order to be effective. Too much negative cognitive feedback –a barrage of interruptions, corrections and overt attention to malformations-often leads learner to shut off their attempts at communication. They perceive that so much is wrong with their production that there is little hope to get anything right. On the other hand, too much positive cognitive feedback–willingness of the teacher-hearer to let errors go uncorrected-serves to reinforce the errors of the speaker-learner. The result is the persistence and the fossilization of such errors. So the task of the teacher is to discern the optimal tension between positive and negative cognitive feedback.

One useful taxonomy of basic error treatment options recommended by Bailey (1985:111) is:

1. To treat or ignore

30 3. To transfer treatment (to say other learners) or not

4. To transfer to another individual, a subgroup, or the whole class 5. To return, or not, to original error maker after the treatment 6. To permit other learners to initiate treatment

7. To test for the efficacy of the treatment

Possible Features: 1. Fact of error indicated 2. Location indicated

3. Opportunity for new attempt given 4. Model provided

5. Error type indicated 6. Remedy indicated 7. Improvement indicated 8. Praise indicated

Brown (1994:222) suggests all of the basic options and features within each option are models of error correction in the classroom.

The teacher needs to develop the intuition, through his/her experience and eclectic theoretical foundations, for deciding which option or combination of options is appropriate. Principles of optimal affective and cognitive feedback, of reinforcement theory, and of communicative language teaching, all combine to form those theoretical foundations.

A general conclusion can be made from the study of errors in the interlanguage systems of learners. It is that learners are creatively operating on a second language in a system for understanding and producing utterances in that language. That system should not be treated as an imperfect system. Learners are processing this language on the basis of

31

knowledge of their own interlanguage. It is the teacher’s task to value learners, prize their attempts to communicate, and then to provide optimal feedback for the learners until they are communicating meaningfully and unambiguously in the second language.

Brown (1994:206) on the other hand warns the teachers and finds it dangerous to pay too much attention to learner’s errors. "While the second language teachers are dealing with errors, the correct utterances may go unnoticed. So the teacher shouldn’t lose sight the value of positive reinforcement of clear and free communication." Diminishing of errors is an important criterion for increasing the language proficiency but in second language learning, getting the communicative fluency in a language is the most important goal .

32 CHAPTER III METHODOLOGY 3. 1. Introduction

The aim of this study is to investigate the origins of errors produced by Turkish learners of English and what sort of difficulties students meet during their mastery of English. In this study, the errors made in the use of prepositions are explored and the reasons are explained On the basis of these errors that they have done, this study also aims at determining if communicative activities are effective in terms of improving students’ prepositional knowledge in grammar.

Accordingly, this research tested the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis : Difficulties with prepositions because of Mother Tongue Interference have been observed for some time by the researcher. The researcher predicts that the students whose teachers use communicative activities such as dialogues and role plays and teach the prepositions in context will score significantly higher on the post-test than the students whose teachers use lists for teaching prepositions and give the meanings. The researcher also predicts that the students whose teachers use communicative activities will score significantly higher on the retention test than the students whose teachers use list of prepositions in the meaning-given method.

Consequently, this chapter describes the research design, subjects, materials, and the data collection procedure.

3. 2. Research Design

In order to test the hypotheses of the study, an experimental and a control group were formed. Each group consisted of eighteen students at early pre-intermediate level. Prior to this

33

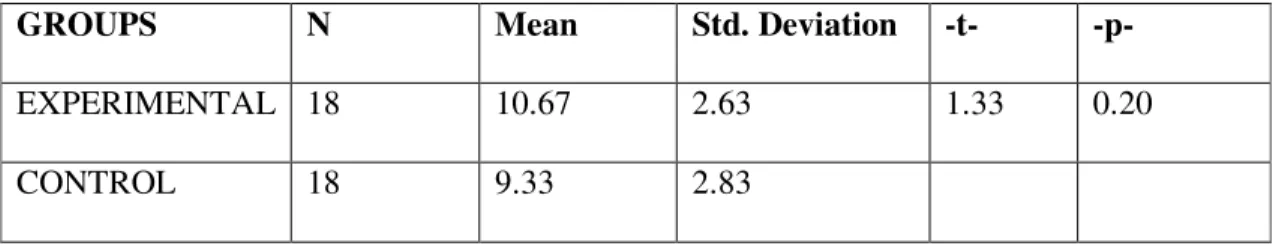

experiment, a pre-test was administered to both the experimental and the control group in order to determine their passive knowledge of the prepositions. The pre-test included thirty-two preposition questions in the form of a multiple choice test with four options.

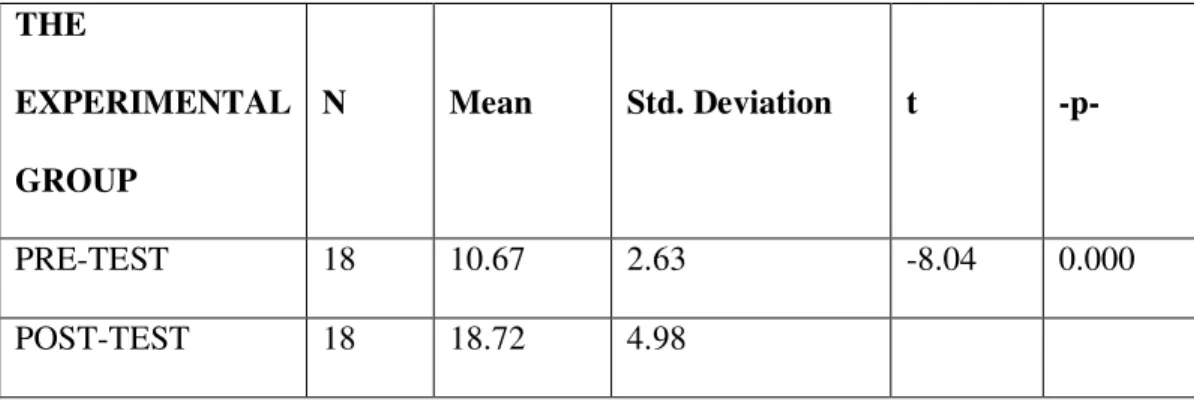

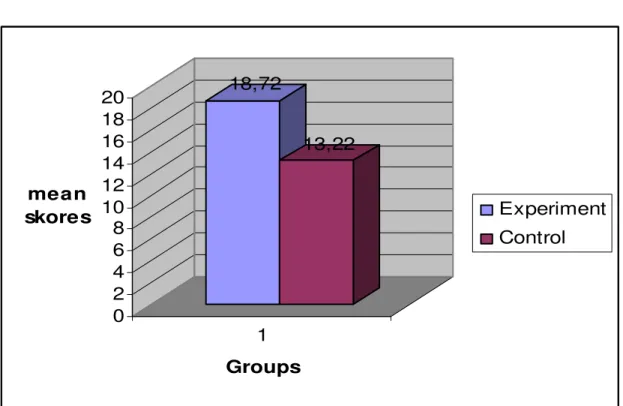

Treatment materials were implemented in four sessions (one session=80 minutes a day) on the same day for four consecutive weeks. In each session, the experimental group studied a dialogue through communicative activities each of which included eight target prepositions. In contrast, control group studied the same text with a list in their hands. Their meanings are given by the teacher. It is also worth mentioning that the teaching process was conducted by the same teacher, the researcher herself.

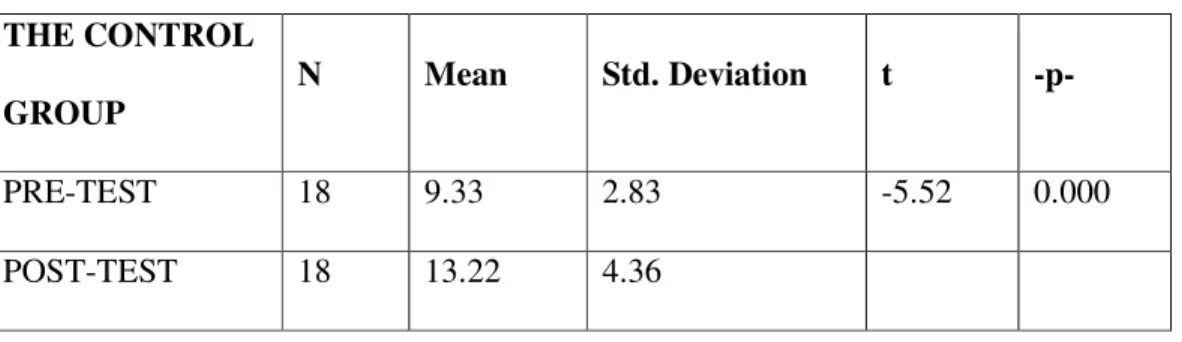

After the teaching process, both groups were given the same pre-test as a post-test. The analysis of the post-test results was used to verify the first part of the hypothesis of this quasi-experimental study. Fifteen days after the post-test, a retention test was carried out in order to test the second part of the hypothesis. Table 1 displays this research design:

Table1. Experimental Design

Pre-test Sessions Post-test Retention Test

Experimental Group - preposition test - 32 preposition questions - Each session: 1 dialogue 8 prepositions - preposition test - 32 preposition questions - preposition test -32 preposition questions Control Group - preposition test - 32 preposition questions - Each session: 1 dialogue 8 prepositions - preposition test - 32 preposition questions - preposition test -32preposition questions

According to this research design, the same preposition test was used as the pre-test, post-test and retention test. In addition, the total number of the new prepositions, some of

34

which are prepositional verbs and some of them are prepositions after adjectives was thirty-two for each group.

3. 3. Subjects

This study was carried out with thirty-six students who were attending intensive Preparatory School Program at Selcuk University, School of Foreign Languages (SOFL). This school is in charge of teaching general English to freshmen for one year before they continue their departments. At the beginning of the term, students take a proficiency exam as a result of which some of the students are exempt from intensive English preparatory program. In contrast, students who fail are classified according to the results of a Placement Test. There are two levels in the preparatory class program, elementary and pre-intermediate. Students are required to take twenty-five hours of English a week.

Two groups were used in the study, and the groups were classified according to the results of the Placement Test that was administered at the beginning of the 2007-2008 academic year. The study started at the very beginning of the second term. Therefore, the subjects were at early pre-intermediate level after having studied in the first term a series of Opportunities as course book and Password for reading and writing published by Longman.

The researcher conducted the study herself as the regular course teacher on prep-class 1-LEVEL-B (experimental group) and prep-class 2-LEVEL-B (control group). The experimental group was comprised of eighteen students: eleven males and seven females. Similarly, the control group was comprised of again eighteen students: eleven males and seven females. The ages of the students in both groups ranged between 18 and 19, with similar social and educational backgrounds.

35 3. 4. Materials

As seen in Table 1 research design, the materials used in this study were a pre-test, post-test, retention test, four dialogues for both groups with different studies. Since this was a quasi-experimental research study with two groups (experimental group, control group) and it has two treatment types for each group, a preposition test was designed in order to assess the effect of treatment types. The participants took the preposition test before and after the treatment sessions as this study had both a within-subject and a between-subject design.

The multiple choice preposition test, which was used as pre-test, post-test and retention test throughout the study, involved thirty-two preposition questions covering the target prepositional items (see Appendix A). In addition, the options were provided within the same preposition items.

These prepositional items were selected from the books, New Headway by John and Liz Soars, English File by Clive Oxenden, Paul Seligson and Christina Latham -Koenig and The New Opportunities by Michael Harris, David Mower and Anna Sikorzynska .These books were studied in different preparatory classes in pre-intermediate level. It is also worth mentioning that multiple choice test type was deliberately chosen since it is more appropriate to test the recognition aspect of knowledge of prepositions.

The materials used with the experimental group during the teaching process were four dialogues. These dialogues were Annoying Habits, Lessons, Love Story and Shopping and the activities are presented in Appendices B, C, D, and E. The targeted prepositions were written in bold face so that students were aware of their learning.

To train the students to infer the meanings of unknown prepositional items with the aid of the context, a short training session was developed that was given within a single lesson.

36

The materials used with the control group during the teaching process were a list of the same prepositions (see Appendix F) which were used in experimental group and the same dialogues with the experimental group (see Appendices G, H, I, and J). The target prepositions were printed in bold and the meaning of unknown word was presented in English. In addition, the students were provided with monolingual dictionaries during sessions so that the students could learn the meanings of unknown items immediately. The subjects in the control group were allowed to look up the dictionary for the unknown words. Thus, they could comprehend the dialogue and this would aid learning.

3. 5. Data Collection Procedure

As mentioned before this study aims to investigate the origins of errors produced by Turkish learners of English and what sort of difficulties students meet during their mastery of English. In this study, the errors made in the use of prepositions are explored and the reasons are explained. On the basis of the errors,this study also aims at determining if communicative activities are effective in terms of improving students’ prepositional knowledge in grammar. The experiment was carried out at Selcuk University, SOFL in the second term of the 2007-2008 academic year. Prior to the experiment, four dialogues were prepared. Within these dialogues, fifty target prepositional items were selected and turned into a multiple choice preposition test having four options. To ensure the test’s reliability, the test was piloted to a hundred first-class students at Selcuk University, SOFL. According to the results of the reliability test, the number of questions was reduced to thirty-two. As a result, the prepositional test involving thirty-two questions was formed and the same test was used as a pre-test, post-test and retention test throughout the study (see Appendix A). As explained before, multiple choice test type was preferred since the study was related to the knowledge of

37

prepositions, so only the recognition aspect was taken into consideration rather than production.

The pre-test was applied by the researcher to the both groups in regular class hours on the third of March. The duration of the pre-test was forty minutes. The subjects were distributed the multiple choice test including the target prepositions and instructed to mark on the answer sheets. The aim of the pre-test was to determine the subjects’ passive knowledge of the target prepositional items. It also formed baselines for the results of the post-test.

As it shown in Table 1, the teaching process had four sessions for both the experimental and the control group. Each session carried out on the same day along the four consecutive weeks; the first session was carried out on the seventh, the second on the fourteenth, the third on the twenty-first and finally the last on the twenty-eighth of March. The duration of each session was 80 minutes. It should also be noted that each sessions covered the same sets of prepositional items for each groups (see appendix F).

The post-test was administered after the conclusion of the teaching process on the seventh of April. The post-test aimed to verify the first part of the hypothesis of the study. Finally, the retention test was given two weeks after the post-test on the twenty-second of April. The aim of this test was also to test the retention. As a reminder, both the post-test and the retention test followed the same content and procedure as the pre-test. Consequently, it should be mentioned that subjects were not informed about the study during either these tests or the teaching process.

3. 5. 1. The Experimental Group

As mentioned before, the experimental group (prep-class 1) had four sessions throughout the teaching process. In each session, the researcher, as the regular class teacher taught eight target prepositional items through one dialogue.