Selçuk University

Institute of Social Sciences

Faculty of Letters

Department of English Language and Literature

Error Analysis:

Mispronunciation of English Consonant Sounds /s/ and

/h/ Preceding Consonants and Vowels by Afghan

Students

MA Thesis

Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Nazli GUNDUZ

Submitted by: Mohammad Shah ZAKI

ÖZET

Bu araştırma İngilizceyi ikinci yabancı dil olarak öğrenmekte olan Afgan öğrencilerin S vs H harflerini yanlış söyleyiş/telaffuz etmelerini araştırdı. İngilizceyi ikinci yabancı dil olarak öğrenen Afgan öğrencilerin, diğer sessiz harflerden sonra gelen S ve sesli harflerden sonra gelen H harflerini yanlış telaffuz ettikleri sonucuna vardık. Farsça ve İngilizce dillerindeki sesli ve sessiz harflerin arka planını detaylıca araştırdık ve ortak noktalarının olup olmadığını bilmek için her iki dili birbiriyle karşılaştırdık. Araştırmamız her iki dilin ünlü ve ünsüz harfler konusunda benzeyen ve ayrışan yönlere sahip olduğunu gösterdi. Araştırmacılar, Afgan öğrencilerin yanlış telaffuz ettikleri S ve H harflerinin yanlış kullanımın nedenini bulmak için bu harflerin kullanımını birbirleriyle karşılaştırdı. Sonuç olarak Afgan öğrenciler için haftada üç gün olmak üzere iki aylık bir telaffuz sınıfı oluşturduk. Çıkan sonuç Afgan öğrencilerin ses sisteminin ve hece yapısının farklı olduğunda diğer sessiz harflerden sonra gelen S harfinden önce schwa /e/ sesini koyduğunu açığa çıkardı. Afgan öğrencilerin sesli ünsüz harflerden sonra gelen S harfinin telaffuzundaki hataları sessiz ünsüz harflerden sonra gelen S harfinin telaffuzunda yaptıkları hatalardan daha fazla idi. Farsça ve İngilizce dillerinde S ve H harflerin telaffuzundaki tarz ve yer çeşitliliği Afgan öğrencilere doğru söyleyiş/telaffuz konusunda zorluklar yaratmıştır. Sessiz harflerden sonra gelen bu harflerin söyleyiş/telaffuzunda hecelerin birincil ve ikincil vurguları yanlış telaffuza sebep olmuştur. Afgan öğrencilerin dillerinin ses sistemleri ve hece yapıları ikinci dilin söyleyiş sistemi üzerine dolaysız etkilere sahip olup yanlış söyleyiş/telaffuza sebebiyet vermiştir. Bulgular S harfinin sesli harflerden önce geldiği durumlarda Afgan öğrencilerin bu harfin söyleyişinde telaffuz hatası yapmadıklarını da gösterdi. Zira Farsça ve İngilizce dillerin her ikisinde de S harfinin ses sistemi ve hece yapısı aynı idi. İşte Bundan dolayı Afgan öğrenciler sesli harflerden sonra gelen S harfinin Söyleyiş/telaffuzunda hata yapmadılar. İki aylık telaffuz sınıfının sonucu Afgan öğrencileri için pozitif idi. Afgan öğrenciler bu iki harflerin söyleyiş/telaffuzunda yaptıkları hataları düzelttiler.

Abstract

This study investigated the cause of misarticulation of English phonemes /s/ and /h/ by Afghan students learning English as a second/foreign language. We have found out that Afghan students having learned English as a foreign language misarticulated both the phoneme /s/ preceded by other consonants, and phoneme /h/ preceded by vowel sounds. We studied the background of Farsi/Dari and English languages consonant and vowel sounds in details and then compared whether these two languages have similarities and differences, or not. The review showed that these two languages had similarities and differences in consonant and vowel sounds. The researchers compared the usage of phonemes /s/ and /h/ to know the cause of misarticulation of these phonemes by Afghan students. As a result, we held up a pronunciation class for Afghan students for three days a week for two months, the findings revealed that when the syllable structure and sound system were different, Afghan students put a schwa /ə/ sound in front of the phoneme /s/ preceded by other consonants. There was more misarticulation by Afghan students when the voiced consonants preceded the phoneme /s/ than voiceless consonants preceded it. The variation of place and manner of articulations of phonemes /s/ and /h/ in both languages created difficulties for Afghan students to articulate them accurately. The primary and secondary stresses on the syllables caused misarticulation of this phoneme followed by consonants, too. Afghan students’ language sound system and syllable structure had their direct influence on second language pronunciation system and caused misarticulation. The findings also declared that when the phoneme /s/ preceded vowel sounds, Afghan students did not misarticulate this phoneme because the sound system and syllable structure of the phoneme /s/ were the same in both Farsi/Dari and English languages. That’s why they did not put a

schwa /ə/ in front of the phoneme /s/ preceded vowel sounds. The result of two months pronunciation class for Afghan students on phonemes /s/ and /h/ was positive and corrected their misarticulation of these two phonemes.

Chapter 1

1. Introduction

It is logical to accept that native English speakers can recognize the foreign accents of non native English speakers, such as Pakistani, Indian and Dari which may affect the intelligibility of certain sounds, but more often it conveys the reality that these people are not native English speakers. English language is the latest “lingua franca” of the world and many people regard it as an official or second language in their hometown. In most countries around the world, English became a language of business, science, media and so on; therefore, many people who are living in developed and undeveloped countries try to learn it as a foreign language. Afghanistan is one of the countries of the world whose young generation is rushing to English language schools and courses in order to better learn the foreign language in its standard ways, so there is a need to do research on the correct use of language pronunciation.

The most important difficulty encountered by every second/foreign English language learner is the achievement of acceptable pronunciation that allows him/her to be understood by the native English speakers, as well as other speakers of English. As a matter of fact, many learners master in some other language elements such as syntax, grammar, semantics, morphology, etc equal to native speakers, but they often fail to master in phonology. According to

Avery and Ehrlich (1992), “the nature of a foreign accent is determined to a large extent by the learners’ L1. In other words, the sound system and syllable structure of the L1 have some influence on the speech or production of the L2” (p. 2). To support this view further, Swan & Smith (1987) explain that, “the pronunciation errors made by second language learners are considered not to be just random attempts to produce unfamiliar sounds, but rather reflections of their native language sound system” (p.x).

During my M.A study in a linguistics class at Selcuk University Konya, Turkey, Department of English Language and Literature Dr. Nazli GÜNDÜZ observed that there was mispronunciation in some English words containing the phonemes /s/ and /h/ by Afghan students and asked us whether we had noticed it as well. Since I got interested in the study of applied linguistics the branch of phonetics, I had become eager to find out the reasons underlying this pronunciation error, and I decided to do a pre-study whether any researcher had already done such a study before in Afghanistan or other parts of the world. I have found out that some linguists carried out a comparative study on Farsi/Dari phonemes and highlighted the point that creates problem for Farsi/Dari speakers while they interact with native English speakers. On their studies, they did not focus deeply about the cause of misarticulation and did not propose the solutions for this critical problem. In this study, I deeply focused on the misarticulation of the phonemes /s/ and /h/ which preceded vowel and consonant phonemes then highlighted the problematic areas and tried to propose some solutions. Mahjani (2003) states in her M.A thesis “An Instrumental Study of Prosodic Features and Intonation in Modern Farsi (Persian)”: “During the last two decades of the 20th century, such experimental investigations have been made for many languages both European and Non-European ones” (p.9). Therefore, after doing a pre-study

on the topic I found out that this study will be useful and practical to Afghan English learners as well as English teachers and devoted my time to do research in the articulation of the phonemes /s/ and /h/ by Afghan speakers of English.

Afghan learners of English mispronounce the phoneme /s/ which comes at the beginning of a word when followed by another phoneme by adding another sound in front of it. Although there is no schwa phoneme /ə/ before the phoneme /s/ in English in words, it is observed that Afghan students articulate a schwa sound in front of this phoneme commonly while reading and speaking English. On the contrary, they do not mispronounce the phoneme /s/ when it is followed by vowel sounds. In addition to, these students also misarticulate the phoneme /h/ when it is followed by vowel sounds. For instance, Afghan students pronounce the English word “happened” not with /h/ sound but softly with /a/ sound, “apppened”. The misarticulation of these phonemes reveals that their native language has a very direct influence on pronunciation of English phonemes.

The primary aim of this research is to investigate the reason of the misarticulation of English phonemes /s/ and /h/ preceding other consonants and vowels in words by Afghan learners of English, so this experimental study will answer the following questions: Why do Afghan students mispronounce the phoneme /s/ when it precedes other consonant letters? What are the reasons and obstacles in mispronounciation of the phoneme /h/? What are the reasons that Afghan students correctly pronounce the phoneme /s/ preceding vowel sounds?

As an Afghan teacher of English, I would like to find out the reasons behind these mispronunciations by doing research on the phonological structures of

the two languages, English and Farsi/Dari. Also, Afghan students articulate the phoneme /h/ like long “ee” or “a” sounds. In general they articulate most of the English phonemes accurately; therefore, the above mentioned issues became very important to do research on.

The overall focus and attempts in this study are to realize why Afghan students misarticulate the above mentioned phonemes. Thus, the study will be accomplished through the comparison of the sound structure of English and Farsi/Dari. The comparison of the two languages will reveal the reasons behind mispronunciations and aid to overcome these errors and enable to propose a practical solutions for Afghan students learning English as a second or foreign language in future at Afghan Schools and Universities.

1.1 The Aim of the Research

The aim of this study is to investigate those areas of language in which Afghan students mispronounce the phonemes /s/ and /h/ of English language. It is very obvious that languages have their differences in almost every linguistic feature, like phonetics, phonology, syntax and semantics. There might be research in each of these features in various languages of the world relating to English, but so far it seems that there was not any research on the mispronunciation of the English consonant phonemes /s/ and /h/ by Afghan students.

Mispronunciation of consonant phonemes /s/ and /h/ by Afghan students has become a crucial problem in the proper learning of English pronunciation; therefore, an error analysis study is going to be conducted. In this study six Afghan students who study through the medium of English at Selçuk University, Konya, Turkey have been requested to take part in this study. This

study focuses on three different aspects of English pronunciation; first is the phoneme /s/ preceding other consonants; second is the phoneme /s/ preceding vowels; third is the phoneme /h/ preceding vowels. Throughout this study, the author tries to define and explain the reason behind the mispronunciation of the phonemes /s/ and /h/ preceding consonant and vowel sounds in English words.

Although some other similar studies have been conducted relating to Farsi/Dari phonology by other researchers such as Mahnaz Hall (2007), Dr. Mitra Ahmad Soltani (2007) and Behzad Majani (2003), in Australia and America, none has been done with respect to mispronunciation of the phonemes /s/ and /h/ in English by Afghan students. The author of this study specifically tries to focus on the phonemes /s/ and /h/ to investigate why Afghan students in this study mispronounce them to propose a practical solution to correct the errors.

1.2 Objectives of the Research

This study initially investigates the phonological characteristic of Afghan students who speak English as a foreign/second language, by focusing on the two phonemes /s/ and /h/.

The author of this research has three main objectives:

1. To examine how Afghan students articulate words in which the phoneme /s/ precedes vowel sounds in texts prepared for this study by the researchers.

2. To find out whether the phoneme /s/ preceding other consonants is pronounced correctly by Afghan students or not; if not, find out the reason behind it and then propose a solution to it.

3. To examine pronunciation of the glottal phoneme /h/ in texts and list of words, and see whether the mispronunciation relates to native language interference or not.

1.3 Significance of the Research

This error analysis study is both important for foreign/second language teachers of English, and foreign/second language learners; especially for Farsi/Dari speakers because it focuses on the phonetic structure of two languages (i.e., Farsi/Dari and English). This study highlights the very outstanding points of misarticulation of English phonemes /s/ and /h/ by Afghan students. The foreign/second language teachers and learners will not only benefit from the findings of this study, but also it will help them to understand the phonological differences which cause difficulties in the articulation of some of the phonemes in English.

Since there is not enough research about Farsi/Dari language in the linguistics field, this research could pave the ways to understanding similarities and differences of its phonological characteristics. This study is also a clue for Afghan English teachers in order to understand the cause of mispronunciation of second language; especially the phonemes /s/ and /h/ when preceding other consonant and vowel sounds.

Finally, I would like to state that this research will open the narrow way towards linguistics study of Farsi/Dari language in comparison to English, and it can be quite valuable for Farsi/Dari phonologists, and those linguists who are interested in learning facts about other languages.

Chapter 2

Literature Review

In this chapter, the background of Farsi/Dari and English consonant and vowel structures and sound system are presented. Furthermore, the author provides specific information about English and Farsi/Dari phonemes /s/ and /h/ and a review about contrastive analysis and errors analyses. According to the information that has been gathered on both languages, the author compares the phonetics and phonology of English and Farsi/Dari consonant letter and sound systems. As a result of this comparison, the problematic areas responsible for pronunciation errors of Farsi/Dari speakers of English as a second or foreign language will be identified.

2.1 A Brief Introduction to Farsi/Dari Language

Farsi/Dari is referred to the language that is popularly known as Persian or Farsi. These different names have been used throughout history and refer to the same language. There are two theories regarding to the origin of the word “Dari”. The first theory is that the word Dari comes from the word Darbar which means court, courts of kings. It has been argued that this language was the very respected and chosen as a language for communications at royal courts of kings. Hence, it is known as the language of courts or Darbari. Later in time the word Darbari was shortened and evolved to Dari which still has the same meaning as Darbari. The second theory relates the origin of the word

Dari to the word Dara (Valley). Many accomplished language researchers admit that the language Dari itself was born in Khorassan, (current Afghanistan), a mountainous area where people live in numerous valleys (Dara). Therefore, the name Dari was coined to refer to the language spoken by people of the valleys (Dara) or in the valleys (Museen, 1995, pp.1-3). Farsi/Dari is a widely used language in Central Asia. It is the official language of Iran, Tajikistan and Afghanistan. Farsi/Dari is a branch of the Indo-Aryan languages, a subfamily of the Indo-European languages. There are three different periods in the development of Aryan languages: Old, Middle, and Modern Periods.

Indo-European

Indo-Iranain

Iranian

Indo-Aryhan Old Farsi/Dari---551 BC Sanskrit

Middle Farsi/ Dari --- 331BC

Modern Farsi/Dari --- 7th century

Table 1: Family of Indo-European Languages

Old Farsi/Dari and the Avestan languages represent the old stage of development and were spoken in ancient Bactria. Old Farsi/Dari was spoken until around the third century BC. Middle Farsi/Dari was spoken from 3rd

century to 9th and was related to several other Central Asian tongues such as Sogdian, Chrosmian and also Parthian languages (Dehgani, 2006, p.10). Modern Farsi/Dari began to develop around 9th century. It is a continuation of the Khorassanian standard language which had considerable Parthian and Middle Farsi/Dari elements. Today it has much simpler grammar than its ancestral forms. After the conquest of Arabs in 7th century, it is written in Arabic script with few modifications and has absorbed a vast Arabic vocabulary.

In Afghanistan, many different ethnic groups live and speak in their own languages such as Farsi/Dari, Pashto, Uzbaki, Turkmani, Pashahee, Noristani and so on, but Farsi/Dari and Pashto are the two official languages of the country. Farsi/Dari language is taught in schools and universities, and Radio Afghanistan is promoting a standardized pronunciation of the literary language. Persian spoken in Tehran serves as a model for more formal style, but some colloquial styles are closer to Tajik. Only minor lexical differences exist between the literary forms used in Iran and Afghanistan. Although both Pushto and Farsi/Dari are the official languages of Afghanistan, Farsi/Dari has a special social status in the country because of its historical prestige; it is the preferred language for communication among speakers of different language backgrounds (Khanlari, 2006, pp.1-5).

2.2 Background of Farsi/Dari Vowels

According to Yamin (2005) there are eight vowel sounds in Farsi/Dari language. Three of them are tense vowels [i: , u: , a: ] and five of them are lax vowels [ e, i , a, u, o ]. The difference between two sets of vowel is in their length. Tense vowels are long, but lax vowels are short. Vowels occur in the following positions:

1- Vowel /a: / comes in three places in the words. In the initial of the words, it appears as the sound / آ, a: / in which Farsi/Dari language has a long sound. In the middle and end of the words, it appears like the sound / ا, a/ which is also a long sound.

Example:

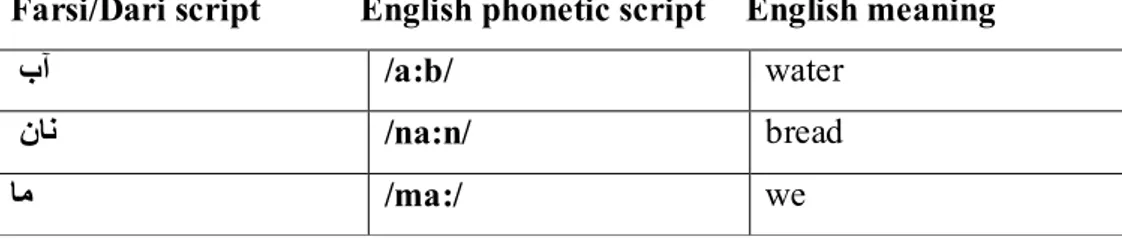

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning

بآ /a:b/ water

نﺎﻧ /na:n/ bread

ﺎﻣ /ma:/ we

Table 2: Farsi/Dari Vowel /a:/

2- Vowel /æ / appears in the beginning of the words like /ا, æ / which represents a short sound, and at the end of the words like // , but when this ه

sound comes in the middle of a word there is no letter to show it; therefore, sometimes it is shown with “fata” symbol / ّ /.

Example:

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning

ﺮﺑا / æbr/ cloud

ﮫﺑ /bæ / to

ﻦﻣ /mæn/ I

Table 3: Farsi/Dari Vowel /a, æ /

3- Vowel /I/ is written at the beginning of the words with letter / / . It does not اِ

appear at the end of the words, but when it comes in the middle of the word there is no letter to represent it. So it is shown with the symbol ِا / / “kasra ya

zaber”.

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning

زوﺮﻣ ِا /Imroz/ today

لِد /dil/ hart

ﺪﻨﭙﺳ ِا /Ispand/ seed

Table 4: Farsi/Dari Vowel /I/

4- Vowel /e/ rarely comes at the beginning of a word alone, but it comes together with “alef” // . In contrast, this vowel comes like (ya /ی /) which is ا

called passive (ya) at the middle and at the end of the words.

Example:

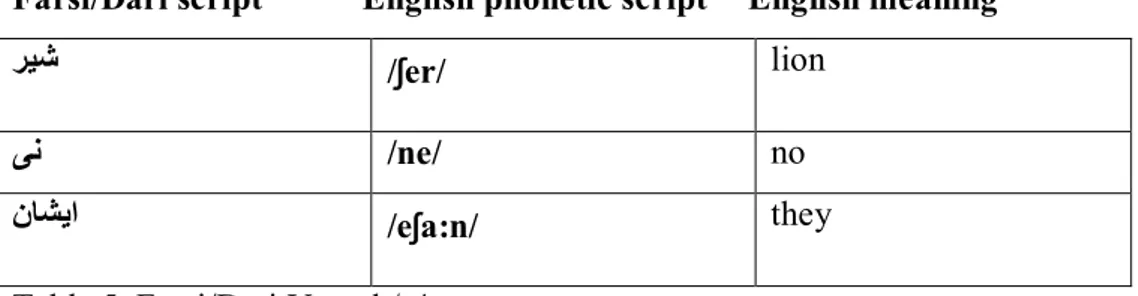

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning

ﺮﯿﺷ /ʃer/ lion

ﯽﻧ /ne/ no

نﺎﺸﯾا /eʃa:n/ they

Table 5: Farsi/Dari Vowel /e/

5- Vowel /i:/ comes at the beginning, middle and at the end of the words. Unlike the previous vowel sound this vowel sound is called active (ya /ی/ ) which is well pronounced in Farsi/Dari.

Example:

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning

ﻦﯾا /i:n/ this

ﺮﯿﺷ /ʃi:r/ milk

ﯽﺳ /si:/ thirty

Table 6: Farsi/Dari Vowel /i:/

Note: if vowel /i:/ which corresponds to Farsi/Dari vowel (ya /ی/ ) comes at the beginning of a word, in this structure the letter / is added before the اِ/ letter /ی/ at the beginning of the word.

Example:

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning ﮕﺘﺴﯾا

هﺎ /I:stga/ station

دﺎﺠﯾا /I:dʒad/ creation

ﻦﯾا /I:n/ this

Table 7: Farsi/Dari Vowel /i: /

6- Vowel /u/ almost always comes at the beginning of a word like “Alef

maznoon” / . أ/ Example:

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning

ودرأ /urdo/ language of Pakistan

ﺪﯿﻣأ /umid/ wish or desire

Table 8: Farsi/Dari Vowel /u/

When vowel /u/ comes in the middle of a morpheme or word, it almost does not have grapheme, so it is shown with “zama” [ ُ ] sound.

Example:

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning

ﻞُﮔ /gul/ flower

ﻞُﻣ /mul/ much or many

ﺮُﺘُﺷ /ʃutur/ camel

Table 9: Farsi/Dari Vowel /u/

Sometimes the vowel /u/ comes like Farsi/Dari waw /و / in the middle of the words. The letter “و ” is called “madola waw” which also shows “zama” / ُ /

sound of the previous letter.

Example:

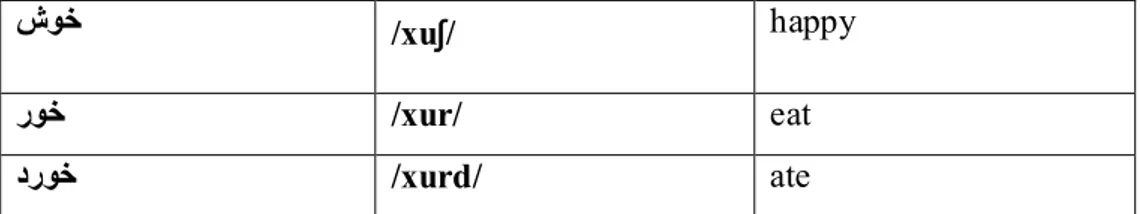

شﻮﺧ /xuʃ/ happy

رﻮﺧ /xur/ eat

درﻮﺧ /xurd/ ate

Table 10: Farsi/Dari Vowel /u/

This vowel sound also comes at the end of the words only in limited situation like the above sound.

Example:

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning

ﻮﭼ / tʃu/ shout on animals to go

ﻮﭽﻤھ /hamtʃu/ so

Table 11: Farsi/Dari Vowel /u/

7- Vowel /o/ comes in the middle and at the end of the words. The letter which represents this vowel in Farsi/Dari is called passive (waw “و “ )

Example:

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning

رﻮﺑ /bor/ brown color

رﻮﮐ /kor/ blind

رﻮﮔ /gor/ grave

Table 12: Farsi/Dari Vowel /o/

8- Vowel /u:/ comes in the middle and at the end of the words, thus its written form is famous in active (waw “و “ ) in Farsi/Dari language.

Example:

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning ﻮﭘ

ود /du:/ two

ﻮﺗ /tu:/ you

Table 13: Farsi/Dari Vowel /u: / (pp. 14-19 &41-45).

Moreover, according to Azim (1996) in some of Farsi/Dari dialects in Afghanistan there is a similar vowel sound system that is the allophone of these three vowels, short / a /, short / I / and short / u /. These vowel sounds are shown with the phonetic sound short /a/. This vowel sound is mostly pronounced in the middle of words by the people of Badakhshan, Takhar, Andarab and Panjsheer provinces in Afghanistan. People of Parwan and Pagman provinces pronounce the vowel sound /a/ at the end of words (p.14).

Example:

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning کﺮﺘﺷﻼﭘ /palaʃturuk/ swallow

قﻼﺸﻗ /qiʃlaq/ village

اﺪﺧ /xuda/ God

Table 14: Farsi/Dari Vowel Sounds /a, I, u/

Example:

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning

ﮫﭽﺑ /batʃa/ boy

ﮫﺷﻮﺧ /xuʃa/ bunch

ﮫﺸﯿﻤھ /hameʃa/ always

Table 15: Farsi/Dari Vowel /a/

The following figure illustrates Farsi/Dari vowel sounds:

u: I:

o e I u a /æ/ a:

Figure 1: Farsi/Dari Vowel Sounds adopted from Yamin (2005: p. 45)

In addition to the above definition about Farsi/Dari vowels and their usage in the words, Negari (2005) a female Iranian scholar, has written in “Persian Language and its Disorderliness Pronunciation” as following:

There were eight Dari vowels in Middle Persian language. Three were short [a, u, I ], and five others were long [a:, i:, u:, e, o]; but today Persian vowel sounds of Iran are: [a, e, o, a:, i:, u: ]. In Farsi the distinction between vowel sounds [a, i, u] and [a:, i:, u: ] are in their quantity, it means that the way they are articulated is different. The time that long vowel sounds take to be articulated is twice longer than short vowel sounds. But today the difference between vowel sounds [a, e, u and a:, o, i:, u: ] is not in quantity but in quality. It means that the way the vowel sound [a] with [a:, e ] with [i: ] and [o] with [u: ] articulation are different. (p.3)

Unlike Farsi/Dari language, Persian has six vowels three of them are tense and three are lax. The three tense vowels are [i:, u:, a:], and the three lax vowels are [a, e, o]. Shademan (2002) acknowledges “the difference between these two sets of vowels is sometimes supposed to be the distinction in length; so lax vowels are short, and tense vowels are long” (p.2). Unlike the English alphabet, there are just three alphabetical characters in Persian for all of these six vowels such as:/ ا /, /آ / , /و /.

The first character, / آ / corresponds to the long or tense /a: /. The second and third characters / و /, / ا / are combined to represent the other five vowels;

therefore, it is difficult and sometimes impossible for a language learner to guess, whether it is [e, a], or [o]. For example, the Farsi/Dari word ( ﺮﮭﻣ ) can be read as the following:

Farsi/Dari script English phonetic script English meaning

ﺮﮭﻣ /mer/ affection

ﺮﮭﻣ /mor/ seal

ﺮﮭﻣ /mær/ wedding gift

Table 16: Farsi/Dari Vowel Sounds /e, a, o/

Consequently, to make a correct guess, one must know the context and the overall meaning of the rest of the sentence. The six vowels of Persian are differentiated by the position of the tongue: high, mid, low; and by the place of the articulation in the mouth where each vowel is produced: front or back. The table below shows Persian vowel sounds (Dehghani, 2006, p.6).

Figure 2: Persian Vowel Sounds

The root or the origin of Farsi/Dari Alphabet is the same as Arabic, but Farsi/Dari alphabet has four extra letters that do not exist in the Arabic alphabet. Negari (2005) and Farkhari (2004) argue in their books “Inadequacy and Difficulties of Alphabets” and “Farsi Language and its Disorderliness of Pronunciation”, that Farsi/Dari alphabet has been divided in to three groups: 1) Four Farsi/Dari specific alphabet letters;

Farsi/Dari English pronunciation Phonetics

چ /cheh/ [tʃ ]

ژ /zh/ [ʒ]

پ /peh/ [p]

گ /gaf/ [g]

Table 17: Original Farsi/Dari Letters

2) Eight pure Arabic language alphabet letters;

Arabic English pronunciation Phonetics

ث /se/ [s] ح /he/ [h] ص /sa:d/ [s] ض /za:d/ [z] ط /ta:/ [t ] ظ /za:/ [z] ع /ayn/ [‘ , ?] ق /qaf/ [q or ﻻ]

Table 18: Arabic Letters

3) The other alphabet letters are mixed between Arabic and Farsi/Dari languages (Negari, pp.1-3) and (Farkhari, pp, 10-11). Farsi/Dari contains thirty two letters. Before discussing the consonant letters of Farsi/Dari, I would like to present the complete consonants in a table:

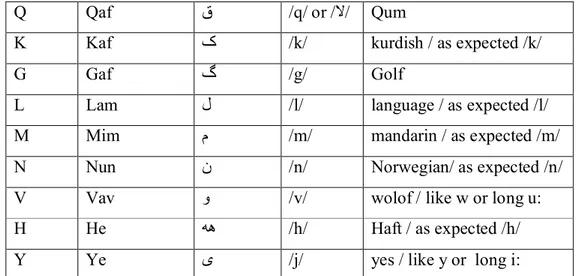

English Farsi/Dari pronunciation Farsi/Dari Scrip IAP symbol Examples

A Alef ا , آ /a/ Apple

B Be ب /b/ book / as expected /b/

P Pe پ /p/ pocket / as expected /p/

T Te ت /t/ teacher / as expected /t/

S Se ث /s/ think / like th in thing / /

J Jim ج /dʒ/ Japanese

Ch Cheh چ /tʃ/ Chinese

H He ح /h/ Hassan / like whispered /h/

Kh Khe خ /x/ Khan

D Dal د /d/ danish / as expected /d/

Z Zal ذ /z/ Like th in these / /

R Re ر /r/ Russian

Z Ze ز /z/ Zulu / as expected /z/

J Je / zhe ژ /ʒ/ pleasure

S Sin س /s/ Spanish / as expected /s/

Sh Shin ش /ʃ/ shadow

S Sad ص /s/ supper / emphatic /s/

Z Zad ض /z/ danish / emphatic /d/

T Ta ط /t/ tagalog / emphatic /t/

Z Za ظ /z/ That / emphatic /dh or z/

', ʔ Ayn ع / ʔ/ ali

Q & G Qein / gein غ /ﻻ/ ghulam

Q Qaf ق /q/ or / /ﻻ Qum

K Kaf ک /k/ kurdish / as expected /k/

G Gaf گ /g/ Golf

L Lam ل /l/ language / as expected /l/

M Mim م /m/ mandarin / as expected /m/

N Nun ن /n/ Norwegian/ as expected /n/

V Vav و /v/ wolof / like w or long u:

H He ﮫھ /h/ Haft / as expected /h/

Y Ye ی /j/ yes / like y or long i:

Table 19: Farsi/Dari Letters which were adopted from Anwari & Giwee (1996)

In the background study of Farsi/Dari phonetics and phonology; there are thirty two letters in the alphabet which are based on Arabic. In Farsi/Dari there are twenty three consonant and eight vowel sounds. It has five lax vowel sounds such as, [a, e, o, u, i ] and three tense ones [a:, i:, u: ]. There are two diphthongs such as [ei] and [ou]. Totally there are thirty three phonemes (Yamin, 2005, pp.41-49).

Farsi/Dari consonant sounds are classified according to their place and manner of articulation which is given bellow:

Place Manner Bila

b ia l Labiodental Alv e o la r P a la ta l V e la r G lo tt a l Voiceless p, پ t - ت k- گ q -ق Stops Plosives Voiced b-ب d- د g-گ Voiceless f- ف s- س ʃ-ش x-خ h-ح Fricatives Voiced z-ز ʒ-ژ g-غ

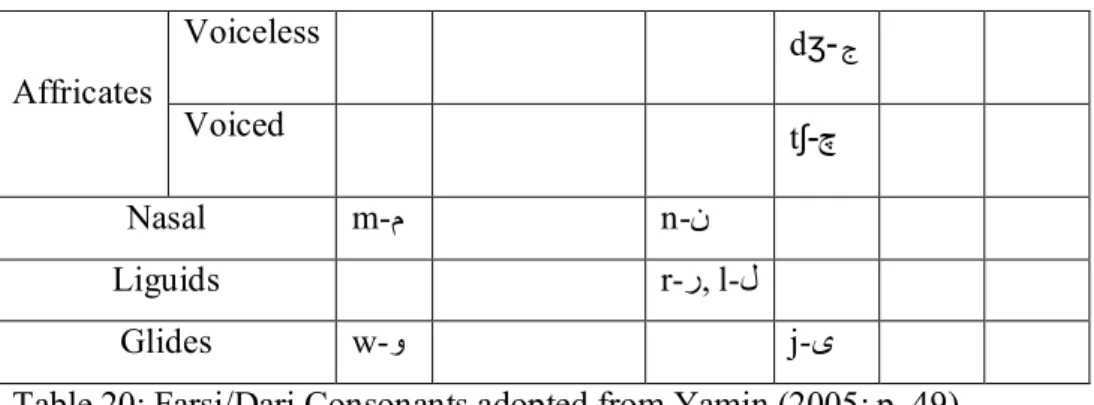

Voiceless dʒ-ج Affricates Voiced tʃ-چ Nasal m-م n-ن Liguids r-ر, l-ل Glides w-و j-ی

Table 20: Farsi/Dari Consonants adopted from Yamin (2005: p. 49)

In his book “Modern Farsi/Dari Grammar” Yamin (2005) defines that there are seven stops or plosives consonant phonemes in Farsi/Dari; [p, t, b, d, k, g,

q]. Four of them are voiceless consonant phonemes, [p, t, k, q]; [p] is bilabial,

[t] is an alveolar; [k] and [q] are velar voiceless consonant phonemes. The other three are voiced consonant phonemes, [b, d, g]; [b] is bilabial, [d] is alveolar, and [g] is velar voiced consonant phonemes. In addition to the above plosive consonant phonemes, there are eight fricative sounds in Farsi/Dari [f,

s, z, ʃ, ʒ, (kh /x/), (g / ɣ /), h] (p.28). Aitken (2006) claims in his article

“Guide to Arabic Pronunciation” that “I could not find the phonetic sound for letter “q” in English to represent it in Latin” (p.1-4). In contrast, Shademan (2002) declares in her thesis “Epenthetic Vowel Harmony in Farsi” that “this [ɣ] symbol represents the phonetic phoneme of the letter “q” ” (pp.6,10,1, 2).

Among the eight fricative phonemes, five of them are voiceless consonant: [f,

s, ʃ, x] and [h]. Thus [f] is a labio-dental; [s] is an alveolar; [ʃ] is a palatal; [x]

is a velar and [h] is a glottal sound. The other three are voiced consonant phonemes, [z, ʒ, ɣ], thus [z] is an alveolar; [ ʒ ] is a voiced palatal; and [ɣ] is a voiced fricative phonemes. There are two affricative consonant phonemes in

Farsi/Dari language; [dʒ] is a voiceless palatal whereas [tʃ] is a voiced palatal consonant. Moreover, it is presented in the consonant table that unlike English Farsi/Dari has two voiced nasal phonemes: [m] is a voiced bilabial whilst [n] is a voiced alveolar nasal consonant phoneme. As last, Farsi/Dari has two liquid alveolar consonant phonemes, [l] and [r], and two approximant or glides: [j] is palatal and [w] is bilabial voiced phonemes (Yamin & Negari, 2005, pp. 1-10 &40-50).

The syllable structure of Farsi/Dari does not start with the vowels, but start with a consonant letter. The important point in Farsi/Dari syllable structure is that, this language does not take two consonants before the vowel. The other important point is that Farsi/Dari does not take more than two consonants in the final syllable of the word. See the example bellow:

CV “ma” /ma:/ meaning “we”

CVC “mar” /ma:r/ meaning “snake”

CVCC “marg” /mærg/ “meaning” death

Table 21: Farsi/Dari Syllable Structure

2.4 Farsi/Dari Phoneme /s/

In the Farsi/Dari alphabet there are three phonemes which correspond to the English phoneme /s/. They are ( ث , /se/, ص , /sa:d/, س , /si:n/ ), they have slight differences in their place and manner of articulations. Among the above three mentioned Farsi/Dari phonemes, it is only /س / that is articulated from the same place of articulation as the English phoneme /s/ is. Others like /ث/ is equivalent to an interdental phoneme /s/ in English, and /ص/ corresponds to a palatal phoneme /s/. Therefore, words which are written with ( ص , ث ,س ) in

Farsi/Dari have /s/ sound in English.

Example:

ﻢﻟﺎﺳ /sa:lem/ healthy

نﻮﺑﺎﺻ /sa:bun/ soup

ﺖﺑﺎﺛ /sa:bet/ stable

Table 22: Farsi/Dari Phoneme /s/

The phoneme /ص is pronounced as a thicker phoneme /s/ in English, and the / phoneme / / ث is articulated as the /th/ phonemes in English as in thing /θIŋ/ (Dehghani & Aitken, 2006, pp.1-4).

2.5 Farsi/Dari Phoneme /h/

There are two phonemes in Farsi/Dari the/ ح /and / / ه which correlate to the

English phoneme /h/. For that reason, words which are written with the phoneme /ح / and /ه / are written with the phoneme /h/ in English; e.g. the words, ﮫﻤھ /hame/ (all) and بﺰﺣ /hezb/ (party). Thus, as we see these characters are unnecessary and only add to the uncertainty in writing, spelling, pronunciation and in general in learning a language. Furthermore, there is no strong and important definition and reasonable approval to write the following words in one or other form. Farsi/Dari bold words are the correct form of the words, but others’ are wrong.

Example:

Phonetic sound English Dari Dari Dari

/sa:lem/ healthy ﻢﻟﺎﺳ ﻢﻟﺎﺻ ﻢﻟﺎﺛ

/sa:bet/ Stable ﺖﺑﺎﺳ ﺖﺑﺎﺻ ﺖﺑﺎﺛ

/sa:bun/ soap نﻮﺑﺎﺳ نﻮﺑﺎﺻ نﻮﺑﺎﺛ

/hæme/ all ﮫﻤھ ﮫﻤﺣ

/hezb/ party بﺰھ بﺰﺣ

The glottal stop is produced by the opening and closing of the glottis; therefore, the glottal stop /?/ is articulated from the area immediately in front of the glottis. It is different from the glottal stop which is produced by a complete closing of the glottis; /h/ is a fricative phoneme and only has a partial closure at the place where it is articulated. Both the glottal stop and the phoneme /h/ are found in English and in Farsi/Dari. The situation in which these sounds are articulated in English, however, is more limited than in Farsi/Dari (Bashiri, 1991, pp. 4-11).

The figure bellow gives much more information relating to the pronunciation of Farsi/Dari letters.

Figure 3: Place and Manner of Articulation of Farsi/Dari Letters

It is noteworthy to mention the origin of the word vowel. In phonetics, a vowel is a sound in spoken language that is characterized by an open configuration of vocal tract, so that there is no build-up of air pressure above the glottis. The word vowel comes from the Latin word vocalis, meaning “speaking”, which in its turn derives from vox/ vocis meaning, voice. In other words, we always perceive vowel as a sound intimately related to the feature of voicedness: vowel is a sound that must be produced with vocal cord vibration (Newmark, 1979, p.15). Furthermore, there is another phonetician Bloomfield (1979) who defines vowels as “modifications of voice-sound that involve no closure, friction or contact of the tongue or lips” (p.2). In addition to the above definition about the vowels, there are still noticeable different view points and disagreements among linguists on the exact number of vowels that exist in English language. There are three different asserts, some expresses that there are twelve; some says eleven and some claims more than twelve. But in general phoneticians define English vowels as twelve; therefore, I will only cover the twelve vowel sounds that appear in the figure bellow (Aitchison, 1999, pp.234-235).

Front Centre Back

Close Close I: u: I H. close Half close 3: e Ə Ɔ:

Half open æ H. open

Λ

a: o

Front Back Figure 4: English Vowel Sounds

I have provided the information about the vowel sounds to present the readers with much more illustration and explanation. The definition of vowel sounds will provide the exact information about the place and manner of articulation in the mouth.

The vowel /i:/ is an unrounded close front long sound, yet the vowel /I/ is a nearly half close palatal front short. Similarly, the vowel /e/ articulates between half open and half close front short, whereas vowel /æ/ articulates between half open and open short unrounded sound. Vowel /ʌ / has the same place of articulation as the vowel /æ/ in the mouth but with a slight difference. /ʌ/ sound is unrounded central short. The vowel /a:/ is open velar unrounded long sound; however, /ɒ/ is a nearly open velar back rounded short. Vowel /ɔ:/ has a place of articulation between half open and half close rounded long; in contrast, vowel /ʊ/ is a nearly half open and half close rounded velar short. There are two other long vowel sounds. One is the nearly close rounded back velar long vowel /u:/. The other is the nearly half close unrounded central long vowel /3:/. In addition to these two vowel sounds, there is a vowel /ə/ which is between half close and open unrounded central short (Andrew & Aitchison, 1999, pp.40-101).

The table below illustrates the complete manner of articulation of English vowel sounds.

Long Short Close Mid Open Unrounded Rounded

u: e I 3: ʌ I u: a: æ u: ə a: e ʊ 3: ɒ ʊ ɔː ɒ æ ɒ ɔː ə ʌ u a: ʌ 3: ə

Table 24: Manner of Articulation of English Vowel Sounds

2.7 Background of English Consonants

According to Sousa (2005) the letters of the English alphabet are based on Latin which contains twenty six letters, twenty four consonants, twelve vowels, eight diphthongs and a total of forty four phonemes (p.37). The following table illustrates the place and manner of articulation of English consonant sounds. Place of Articulation. Manner of Articulation B ila b ia l L ab io - D en ta l D e n ta l o r In te rd e n ta l A lv e o la r Alveo- Palatal (palatal-alveolar, Postalveolar) P al at al V e la r G lo tta l Stops / Plosive p b t d k g ? Fricatives v f θ ð z s ∫ ʒ h Affricates tʃ

Nasals m n ŋ Lateral / Liquids l Retroflex(flap, trill) r Glides / Semi-vowel w j(y)

Table 25: Place and Manner of English Consonant Sounds

The table of the consonant sounds shows that there are seven plosive or stop consonant sounds which are articulated by the air being completely blocked in the mouth and then suddenly released. Among these seven, four of them are voiceless, /p, t, k,?/, whilst three others are voiced, /b, d, g/. Consonants /k/ and /g/ are pronounced when the back of the tongue rises to the velum and blocks the air for a short time; therefore, they are velar plosive, as in keep and

game. Others are bilabial plosive sounds, /p/ and /b/ and alveolar plosive

sounds /t/ and /d/ respectively, as in peak, beat, team and deam. Eventually, the glottal voiceless strongly articulated sound [?] is formed in the glottal region by closing the vocal cords together and then setting them apart. To produce this sound the airstream completely blocks and then releases suddenly, as in “geography”, /I?ogrəfI/ .

English has nine fricative sounds, when you articulate them the two parts of the mouth come close to each other. They do not completely block the air passage, but force it through a restricted and limited space. The English consonant fricatives sounds are labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/ sounds as in

feet and very; dental fricative [θ] and [ð] sounds as in think and this. /s/ and

as in sheep; and [ʒ] sound as in measure, and the glottal fricatives /h/ sound as in happy. In addition to the above explanations about the place of articulation, five of them are voiceless sounds, /f, θ, s, ∫, h/ and the rest are voiced, /v, z, ð, ʒ/ (Andrew, 1999, pp. 31-39).

Another observation is that English has two affricative sounds [tʃ] and [] which are voiceless and voiced respectively. To articulate them the air initially blocks, and then releases through a narrow passageway like a friction; for that reason, they are really plosive and fricative combined sounds. [tʃ] and [] sounds are usually classified as palato-alveolar or postalveolar affricates, as they are articulated in a position half way between the alveolar ridge and the hard palate (Adrian, A. et al., 2001, pp.75-78).

Nasals /m, n/ and [ŋ] are other important consonant sounds which have the same manner of articulation; yet their places of articulations are various. /m/ is a voiced bilabial, /n/ is an alveolar, and [ŋ ] is a velar sounds. Chomsky and Halle (1968) define this as “English nasal consonants stop as the airstream is completely blocked when these consonants are uttered; but they are not considered plosive sounds as their release stage differs from that of oral stops”(p.15).

The liquids are approximant sounds produced in the alveolar and postalveolar region to include several variants of the lateral /l/ and the rhotic /r/ as in words hard and far. The main modification or form of /l/ is named a “clear” /l/ and a “dark” /l/. The clear /l/ is allocated in prevocalic positions. The tip of the tongue touches the alveolar ridge while this sound is pronounced and released the air either unilaterally or on both sides of the active articulation. As a

further matter, the front part of the tongue rises towards the hard palate and releases the air from two sides of the tongue, for instance the words, lake,

look, flute and lurid. The dark /l/ is distributed in final position of words

before a consonant and intervocalically. Unlike the clear /l/ it is the body of the tongue that lifts up against the soft palate, changes the resonance of the sound and gives the dark /l/ more stifled character, in words, kill, rule, belfry, belt, silk (Demirezen, et al., 1987, pp.16, 17, 54).

Finally, there are two approximant or semi-vowel sounds in the English language; /w/ and /j/. Both are voiced sounds: /w/ is a bilabial-velar rounded sound, and /j/ is an unrounded palatal semivowel sound.

According to Chomsky and Halle (1968): When we articulate a glide the articulatory organs start by producing a

vowel-like sound, but then they immediately change their positions to another sound. Unlike vowels, they cannot occur in syllable-final position, can never precede a consonant and are always followed by a genuine vocalic sound. (pp. 8-15)

When phoneme /w/ comes at the beginning of a word, its articulation is similar to the vowel sound /u/, and the organs of speech shift to a different position to produce a various vocalic sound, as in win, weed, wet. On the contrary, the beginning stage of /j/ articulation is quite the same to the short vowel sound /I/, but then the sound glides to a different vocalic value. Similar to /w/, /j/ cannot appear at the end of a word. It is never followed by a consonant and comes in front of back, central and front vowel sounds, for instance yes, young, youth (Bloomfield, 1979, pp.3-8).

2.8 English Phoneme /s/

The English phoneme /s/ is an alveolar, voiceless, fricative sound which is articulated with the blade of the tongue against the alveolar ridge. The breath stream strikes the teeth to produce the hissing sound when the air is forced through the narrow groove formed by the tongue. The phoneme /s/ is positioned at the beginning, middle and at the end of words, as in speaks, test and talks.

Although the phoneme /s/ is frequently represented by the letter “s” as in sun or bus, this letter is quite unreliable because it can stand for the other sounds as well. In addition to the phoneme /s/, this letter can stand for sound /z/ as in rose, is, dogs, dessert, and reason; [ ∫ ] sound as in sure, sugar; [ ʒ ] sound as in measure and pleasure. Furthermore, when the phoneme /s/ is followed by the letter “c”, the two letters can stand for the /sk/ sounds as in scold, or the “c” can be silent as in science or scent. When the phoneme /s/ is doubled in words as in kiss, lesson, dress, and kindness one /s/ is silent, and when the /c/ precedes phonemes /I, e, or y /, it is pronounced /s/ not /k/ as in, circle, cent,

cycle, and face. The /s/ is silent in words like corps, island, and viscount

(Radford, 1999, pp.31-47).

2.9 English Phoneme /h/

The glottal English phoneme /h/ is a voiceless, fricative sound that is produced by letting the air pass freely through the mouth during expiration. English has two glottal phonemes; one is the glottal stop /?/, and the other is glottal fricative /h/. English /h/ is actually a hissing sound, articulated by spreading the vocal folds and letting the air pass out through the glottis. This phoneme appears at the beginning, middle and end of the words, yet dropping the /h/ is even considered as a sign of lack of education. The phoneme /h/ is

silent in initial and medial positions in these words, hour, heir, honor, honest; and medial position in vehicle, annihilate. It is also common even for educated people to drop the initial /h/ in unstressed or weak forms of the personal pronouns he, him, possessive his, her or the verb have. /h/ is also silent in final position and in interjection ah or in the word shah. The traditional spelling of English has maintained the phoneme /h/ after /r/ in words of Greek origin where no /h/ sound or aspiration is heard nowadays like in words, rhapsody, rhetoric, rheumatism, rhinal, rhinoceros, rhombus, rhyme and rhythm.

The phoneme /h/ always precedes vowel sounds, but in the digraph /wh/ the /h/ sound is vocalized before semi vowel letter /hw/. /h/ sound is most frequently represented by the phoneme /h/ as in hat. The only other notable spelling of the phoneme /h/ is /wh/ as in who, whom, and whose. The phoneme /h/ is a pretty reliable phoneme when it appears at the beginning of words. However, sometimes it is silent as in heir, honor, honest, and hour. The phoneme /h/ is silent when it follows the phonemes /g, k / and /r / as in

ghost, rhyme, and khaki. The phoneme /h/ is used in combination with other

consonants to form the following six digraphs: /sh, th, wh, ch, ph, and gh /. The digraph /gh/ may cause confusion, sometimes it stands for the sound /f/ as in enough and laugh; other digraphs are silent as in night and though (Peter, 2000, pp.10, 35, 48,69).

The syllable structure of English is different from Farsi/Dari; for instance, English syllable structure starts with vowel sound (V, VC, VCC, etc.), one or more than one consonant (CV, CVC, CCV, CVCC, CCVCC, CCVCCC, etc.), but Farsi/Dari syllable does not start with vowel sound as clarified in below table:

V I /i/ VC am /æm/

VCC Ant /ænt/ CV key /ki:/

CVC Car /ka:r/ CVCC talk /ta:lk/

CCV tree /tri:/ CCVC trap /træp/

CCVCC stamp /stæmp/ CCVCCC spends /spends/

Table 26: English Syllable Structure

According to Hall (2007):

The difference in the number of syllable pattern may cause problems for [Farsi/Dari] speakers of English in pronunciation. These speakers often have difficulty producing English words with consonant clusters, which is caused by the fact that [Farsi/Dari] does not allow a word to begin with two consonants. (2007, p.28)

Moreover, Shademan (2002) declares:

If a consonant’s features are compatible with the vocalic features of spreading, the inserted vowel is a copy of the following vowel (i.e., the vowels share their features). However, when a consonant’s features are not compatible with the feature being spread, the default vowel /e/ will be inserted. It should be noted that all SC (S + Consonant) clusters have epenthetic /e/. (pp. 28 – 29)

2.10 Contrast between Farsi/Dari and English Vowel Sounds

As mentioned above Farsi/Dari has eight vowel sounds. Three of them are long and five of them are short vowels. The long vowels are: [i:, u:, a:] and the short vowels are [a, e, o, u, i] so the distinction between the two sets of vowels are sometimes assumed to have a difference in length. In the contrary, English has twelve vowel sounds. Five of them are long, and seven of themare short. Farsi/Dari has four front and four back vowel sounds, whilst English has four front, three central and five back vowel sounds. Therefore, Farsi/Dari speakers may not be able to articulate all of the English vowel sounds at first, while they learn the English language. The English vowel sounds that do not exist in Farsi/Dari may be replaced with the nearest Farsi/Dari vowel sounds. For instance, Farsi/Dari speakers have problem with the English vowel sound /I/ as in did. Its sound falls between the Farsi/Dari /i:/ and /e/ sounds; furthermore, they may face difficulty in contrasting seat /si:t/ with sit /sIt/ and sit /sIt/ with set /set/. Farsi/Dari speakers often replace the vowel sound /I/ from English with Farsi/Dari vowel /i:/ and pronounce ‘did’ like ‘di:d’, when they speak. It is considered that Farsi/Dari speakers have problem in the articulation of the English mid vowel /ə/; this sound comes mostly at the beginning of unstressed syllables and replaces with Farsi/Dari vowel /e/ which is similar to the English sound as in bet by Farsi/Dari speakers (Shademan, 2002, pp. 4, 7).

According to Kheshavarz & Indram (2002):

The vowel systems of English and Farsi/Dari differ in size and phonetic quality. English has several vowel phonemes, including tense-lax pairs and diphthongs. General American English, for example, has 13 vowels and 3 diphthong phonemes, and several of the vowel phonemes are phonetically diphthongs, for example, [e, ei ], Farsi/Dari has a small inventory of only eight vowels, three front [i:, e, a, i] and three back [u:, o, a:, u], without the English tense-lax difference. (p.258)

For the further distinction between Farsi/Dari and English vowel sounds we can first review the division bellow and then compare the eight Farsi/Dari vowel sounds with English ones which have nearly the same sound systems:

Vowels Front Central Back

English i: , I, e, æ 3:, ə, ʌ u:, u, a:, ɔː, ɒ

Dari i: , e, a, i u: , o, a: , u

Table 27: Comparison of English and Farsi/Dari Vowel Sounds

1- Vowel /i:/ is close front long in Farsi/Dari which is pronounced roughly the same as the English double “ee” in the word seen. The difference is in the

y-glide that follows the English /i/. The Farsi/Dari vowel /i:/ does not precede

this glide:

Farsi/Dari pronunciation English

/si:n/ seen

/bi:n/ een

/ki:n/ keen

/di:n/ dean

Table 28: Farsi/Dari Vowel Sound Long /i:/

2- Farsi/Dari vowel /u:/ is close back long which is pronounced almost always the same as the English double “oo” in word mood. The distinction lies in the

w-glide that follows the English /u/. Farsi/Dari vowel /u:/ is not followed by

such glides.

Farsi/Dari pronunciation English

/ru:d/ rude

/mu:r/ moor

/pu:l/ pool

/tu:r/ tour

Table 29: Farsi/Dari Vowel Sound Long /u:/

3- Farsi/Dari vowel /o/ is near half close back short which is pronounced roughly like /o/ in the English word goal. The difference is in w-glide that

follows the English sound. The Farsi/Dari vowel /o/ does not follow such a glide.

Farsi/Dari pronunciation English

/gol/ goal

/to/ two

/do/ dough

/bon/ bone

Table 30: Farsi/Dari Vowel Sound Short /o/

4- Farsi/Dari vowel /e/ is nearly half close front short which is fairly close in pronunciation to the English vowel /e/ as in the words, bed and pen.

5- Farsi/Dari vowel /æ/ is open front short which is pronounced approximately the same as /a/ in English word bad, so the difference sets out in the up side down e-glide that follows the English sound. The Farsi/Dari vowel /æ/ does not follow the glide.

Farsi/Dari pronunciation English

/jæm/ jam

/ræm/ ram

/sæd/ sad

/dæm/ dam

Table 31: Farsi/Dari Vowel Sound Short / æ /

6- Farsi/Dari vowel /a:/ is open back long which is fairly close in pronunciation to the English vowel /a:/ as in the word father (Bashiri, 1991, pp.5-10).

7- Farsi/Dari vowel /u/ is half open short back which is close in pronunciation to the English vowel /o/, for example in words, urdu, ordo, full, fol.

8- Farsi/Dari vowel /i/ is half open front short which is close in pronunciation to the English vowel /I/, for example in words, sit, sit, dig, and dig (Bashiri, 1991, pp.5-10 and Yamin, 2005, pp.30-41 ).

2.11 Contrastive Analysis

According to Valdman (1966) Contrastive Analysis (CA) developed in the middle of the twentieth century as a hypothesis of second language acquisition and applied linguistics in order to make comparison and contrast two languages. Contrastive Analysis is a process derived from a behaviorist approach to learning, and it is believed that errors which produced by second language learners are the result of interference from the learners’ native language. Contrastive Analysis is the process of comparing the structures of two languages to each other for the aim of determining the level of difference between the two languages, as well. It was believed that through the comparison and contrast of the learner’s language and the target language, the particular interruption could be both identified and addressed via extra instruction to overcome the difficulties.

Croft (1980) illustrated Contrastive Analysis to teaching as following:

…..the most effective materials for foreign language teaching are based upon a scientific description of the language to be learned carefully compared with a parallel description of the native language of the learner. (p.92)

Contrastive Analysis was one of the most influential approaches to teach L2 in the middle of twentieth century. It is also very important for bilingual education, as Contrastive Analysis represents one of the first direct applications of theory to the development of methods and materials for teaching an L2. Furthermore, Contrastive Analysis is observed as the forerunner to the development of the field of Applied Linguistics for bilingualism and bilingual educators (pp.80-287).

The aim of Contrastive Analysis is to predict and foretell linguistic difficulties experienced during the acquisition of a second language. It proposes that difficulties in acquiring a new language are derived from the differences between the new language and the native language of a language learner. In this regard, it is predicted that second language learners are likely making errors because of the interference of their native language. According to Mackey (1967) learning to speak a foreign language is the acquisition of an ability to express oneself in different sounds and different words through the use of a different grammar. Any sounds, words or items of grammar of the foreign language may or may not have counterparts in the native language. And these counterparts may have meanings, or content, which are similar to or notably different from those of the other languages. Contrastive Analysis involves not only the analysis of two languages, but also a comparison of the differences in separate items and of the way they work together. It covers all levels of language and the relations between them as in phonetics, grammar, lexicology, and stylistics usage. Therefore, Contrastive Analysis is the comparison of similarity and equivalent parts of two languages for the purpose of separating the most likely problems that speakers of one language will have in acquiring the other (p.80).

Moreover, Brown (2000) defines:

It is descriptive linguistics which has contributed to the development of Contrastive Analysis by which two languages can be systematically compared on all levels of their structures. Contrastive Analysis has organized the comparison of languages, has sharpened the forms and perspective of the resulting descriptive statements, so they can be truly useful to the language teacher, who has not always been convinced that he needed the linguist’s help. (p.80)

Contrastive Analysis is useful when one is teaching a group of students with a common language background, textbooks, teaching item selections, subject matter and practice drills. Therefore, all these may be developed with Contrastive Analysis in a particular and certain group (Brown, 2000, p. 213).

2.12 Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis (CAH)

The Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis (CAH) provided information about problematic points for the second language learners and highlighted the ways to solve this problem. It revealed that errors are not something new for the second language learners when they learn a language. It is obvious that languages have their similarities and differences, so second language learners do not have problem when there are similar points between the native and target languages. On the contrary, the second language learners encounter problems when they interact because of structural variations in native and target languages. Additionally, through the knowledge about native and target languages differences, the researcher could easily overcome the problems and propose the solutions for them.

Furthermore, the principle of transfer has been suggested to be psychological foundation of CAH which comes in two basic types: positive or negative. Positive transfer will occur if learners’ L1 structure is similar to their L2; in this case, it facilitates due to the fact that learners would face no difficulties since what they have learnt in their L1 learning situation is positively transferred into the L2. On the other hand, negative transfer occurs when the structure of the L1 is dissimilar to that of the L2. This difference is problematic and causes interference as it delays the learning of the L2. The CAH that came out from considerations of language universals is often referred to as the strong version of CAH because it posits that it can predict

difficulties that a learner will encounter. Robinett & Schachter (1983) provide an explanation of the weak version of the CAH:

The weak version requires of the linguist only that he use the best linguistic knowledge available to him in order to account for observed difficulties in second language learning. It does not require what the strong version requires, the prediction of those difficulties and conversely, of those learning points which do not create any difficulties at all. The weak version leads to an approach which makes fewer demands of contrastive theory than does the strong version. It starts with the evidence provided by linguistic interference and uses such evidence to explain the similarities and differences between systems (1983, p.8).

The weak version of CAH, in explaining error source rather than predicting difficulties, is more useful in these conditions simply because predictions of difficulties often did not materialize as predicted or at all.

2.13 Error Analysis

The field of Error Analysis in Second Language Acquisition (SLA) was established in the 1970s. A key finding of Error Analysis has been that many learner errors were produced by learners misunderstanding the rules of the new language. Error Analysis is a kind of linguistic study that focuses on the errors that learners make. Error Analysis only investigates what learners do. Learners who avoided the sentence structures which they found difficult due to the differences between their native language and target language might have no difficulty to learn a language (Brown, 2000, p. 214). Furthermore, Corder (1967) strongly highlighted that systematically analyzing errors made by language learners make them possible to specify areas that need reinforcement in teaching (p.217).