CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF TWEETS AND ENTRIES OF DISSIDENTS IN TURKEY:

THE IRRESISTIBLE LURE OF VOTING

A Master’s Thesis

by TUĞÇE İNCE

Department of

Political Science and Public Administration İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University

Ankara August 2019

CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF TWEETS AND ENTRIES OF DISSIDENTS IN TURKEY:

THE IRRESISTIBLE LURE OF VOTING

The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of

İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University

by

TUĞÇE İNCE

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN POLITICAL SCIENCE

THE DEPARTMENT OF

POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY

ANKARA

ABSTRACT

CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF TWEETS AND ENTRIES

OF DISSIDENTS IN TURKEY:

THE IRRESISTIBLE LURE OF VOTING

İnce, Tuğçe

M.A. Department of Political Science and Public Administration Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Meral Uğur Çınar

August 2019

Turkey had 12 major political elections in last 10 years. Such intensive election

environment had profound impacts on voters. Especially after the elections

conducted in 2018 and 2019 many dissident voters first stated on online websites that

they will abstain from political elections, and yet later on stated that they actually

voted after all. In this paper, through a discourse analysis of statements of dissident voters on online platforms such as Twitter and Ekşi Sözlük, I will demonstrate what

accounts for turnout among dissidents in Turkey. There are 3 main factors, which are political, social and psychological factors, revealed around the dissidents’ statements.

According to 750 online posts on Twitter and Ekşi Sözlük out of countless many,

most of the dissidents went to the ballot box as a reaction to polarized political

environment generated by the ruling party AKP and to say that they exist and will

not yield to black propaganda. In relation with political factors, such as polarized

political environment and political figures which attracted dissidents, voters cast

their vote since their social circles (families and friends) influenced them to do so.

As a third factor, psychological factors brought dissidents to the ballot box by mostly

important to see that in a hybrid regime like Turkey voting is not only a fundamental

act of political participation but also a struggle for life for the opposition.

ÖZET

TÜRKİYE’DEKİ MUHALİFLERİN TWEET VE ENTRY’LERİNİN

SÖYLEV ANALİZİ:

OY VERMENİN KARŞI KONULAMAZ CAZİBESİ

İnce, Tuğçe

Yüksek Lisans, Siyaset Bilimi ve Kamu Yönetimi Bölümü Tez Danışmanı: Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Meral Uğur Çınar

Ağustos 2019

Türkiye siyasi tarihinin son 10 yılı 12 politik seçimle şekillendi. Böylesi yoğun

seçim atmosferinin seçmenler üzerindeki etkisi ise oldukça derin oldu. Özellikle

2018 ve 2019 yıllarında gerçekleştirilen seçimlerin hemen ardından birçok muhalif

seçmenin artık seçimlerde oy kullanmacayacaklarını sıkça duyuyor, sosyal medyada

bu kararlarına dair paylaşımlarını görüyorduk. Ancak, aynı muhalif seçmenler her

yeni seçim döneminde, önceki söylemlerine rağmen, yine de sandığa gidiyor ve oy

kullanıyorlardı. Bu tez çalışmasında, muhaliflerin seçim sonralarında oy vermeme

yönündeki kararlarına etki eden, onları çekimser kalmaya iten faktörlerin neler

olduğunu ve bu söylemlerine rağmen her yeni seçimde nelerden etkilenerek oy

verdiklerini, muhaliflerin Twitter ve Ekşi Sözlük gibi sosyal medya

platformlarındaki paylaşımlarının kritik analizini yaparak açıklamaya çalıştım.

Seçmenlerin oy verme eylemiyle aralarındaki bu gitgelli ilişkiye etki eden 3 ana

etmen bulunmaktadır: politik, sosyal ve psikolojik etmenler. Sayısız birçok seçmen

paylaşımı arasından seçtiğim 750 Twitter ve Ekşi Sözlük paylaşımına göre,

seçmenlerin kararlarını etkileyen politik etmenleri polarize olmuş siyasi ortam, AKP

tarafından yürütülen kara propaganda, muhalefetin ilgisini çekmeyi başarmış siyasi

figürler oluştururken; sosyal etmenleri muhaliflerin sosyal çevrelerindeki insanların (aile, arkadaş ve komşu gibi) etkisi oluşturuyor. Psikolojik etmenler ise oy vermeye

ve oy sandığına yüklenen duygusal anlamlar dolayısıyla sandığa gitmek zorunda

hisseden muhaliflerin kararlarına etki ediyor. Bunlar gösteriyor ki, Türkiye gibi bir hibrid rejimde oy vermek basit ve aslında çoğu zaman işlevsiz bir siyasi katılım yolu

olmaktan çok, muhalefet için bir varoluş mücadelesidir.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... ii

ÖZET... iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... vi

LIST OF FIGURES ... vii

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ... 1

1. Political Environment in Turkey ... 2

CHAPTER II: SOCIAL MEDIA AS A SOCIAL SPHERE: WHY TWITTER AND EKŞİ SÖZLÜK? ... 11

CHAPTER III: THEORETICAL AND METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK .... 18

1. Political Factors ... 24 A. Political Atmosphere... 25 B. Political Figures ... 43 2. Social Factors ... 52 3. Psychological Factors ... 64 4. On Social Media ... 71

CHAPTER IV: DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION ... 76

REFERENCES ... 84

APPENDICES ... 92

A. DATA RELATED TO ELECTION RESULTS ... 92

LIST OF FIGURES

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

Dissident citizens in Turkey began to lose faith in democracy and democratic Turkey

especially in recent years. The most typical example of this situation lies behind the

voting processes of dissidents. Decisions of dissidents regarding electoral

participation have undergone sharp changes between elections took place in last two

years. Dissidents declared that they would not vote any more after each election,

which resulted in defeat of the opposition and several fraud allegations each time.

However, it is interesting that such statements among dissidents were not reflected

on the ballot box. Dissidents who stated that they would never vote again went to

cast their vote in each and every election. What was the reason made dissidents state

that they would abstain from voting at the first place? What did eventually affect and

lead them to vote despite their earlier statements? What does the meaning of voting

constitute for dissidents in Turkey? How is this kind of voting process among

dissidents related with Turkey’s regime dynamics? I wrote this thesis to find answers

to these questions, which I collected under the same question: What does account for

qualitative method of discourse analysis to examine statements of dissidents on online platforms such as Twitter and Ekşi Sözlük, two of mostly used social media

websites in Turkey, since these platforms provide for people a social place to share

their opinions on almost anything, including politics. Before going further in details

of my findings, I want to take a picture of Turkey in order to demonstrate in what

kind of a regime people live a life in Turkey and how this may affect dissidents’

electoral behavior.

1. Political Environment in Turkey

Turkey had 12 political elections in last 10 years. The list of elections is as followed:

23 June 2019 Local Elections in Istanbul1

31 March 2019 Local Elections

24 June 2018 Presidential Elections

24 June 2018 General Elections

16 April 2017 Referendum on Constitutional Change

1 November 2015 General Elections

7 June 2015 General Elections

10 August 2014 Presidential Elections

30 March 2014 Local Elections

12 June 2011 General Elections

12 September 2010 Referendum on Constitutional Change

29 March 2009 Local Elections

From local to general elections, from presidential elections to constitutional

referendums Turkish people had several chances to actively participate in politics.

1 According to YSK (Supreme Election Council), 8.925.166 out of 10.570.354 voters went to the polls

on 23 June 2019. Due to greatness of voter numbers and the significance of Istanbul Mayoral Election for the rest of the country, I acknowledge the 23 June Elections as another major election rather than a re-election in a particular local election. See Appendix A.

Yet, in most of them2 nothing actually changed in favor of the opposition. All

experienced by the opposition parties and their supporters was another defeat by the

ruling party AKP (Justice and Development Party). There were several elections in

the name of democracy for the country; still there was never development of

democratic institutions as a whole. In fact, according to the Freedom House Report

2019, with score of 31 out of 100 Turkey is classified as a not-free country:

After initially passing some liberalizing reforms, the AKP government showed growing contempt for political rights and civil liberties, and its authoritarian nature has been fully consolidated since a 2016 coup attempt triggered a more dramatic crackdown on perceived opponents of the

leadership. Constitutional changes adopted in 2017 concentrated power in the hands of the president, and worsening electoral conditions have made it increasingly difficult for opposition parties to challenge Erdoğan’s control.

Especially due to election processes Turkey is subject to harsh criticism both in the

Freedom House Report and OSCE Reports. From HDP (Peoples’ Democratic Party) leader Selahattin Demirtaş, who had to carry out an election campaign from the

prison during the presidential elections to media that mostly propagates in favor of

the ruling party AKP; HDP municipalities which are often referred to as terrorist /

terrorist supporters; appointing a trustee to the allegedly corrupted CHP (Republican People’s Party) municipalities; election campaigns conducted in an unequal and

unfair environment due to the use of resources in favor of the government; the YSK's

unexpected decision to count the unsealed votes on the election day; the high

election threshold; the highly oppressed opposition; intransparent administration and

checks and balances system, Turkey presents an unfortunate portrait concerning country’s democracy (OSCE Reports).

2 For the first time in almost 20 years, the ruling party AKP tasted severe loses in municipal elections

on 31 March and 23 June 2019. Until these dates the ruling party won every election only by itself or with its ally MHP (Nationalist Movement Party).

Nevertheless, ballot box is the spring of AKP governments’ legitimacy of

democratic-or-not actions by the help of majority of votes they gain in elections.

Whatever comes as an issue to be discussed publicly, AKP points at elections they

gain to justify what has been done by referring them as national will (Milli İrade).

What is in the background is that, over the years, many democratic institutions and

organizations have been exploited and the entire burden of democracy has been

placed on the shoulders of political elections only. This, in turn, led severe falls of

the country in the ranks of democracy indexes, and that followed by the change of

the regime in the country. According to the Democracy Index 2018, Turkey is the

only country in Europe with a hybrid form of government. Among democracies rated out of 10, Turkey’s score is 4.37 and placed as 110th among 167 countries. The

country score, which was 5.70 in 2006, decreased by 1.33 points in 13 years during

AKP period.

According to the report, Turkey with scores of 4.5, 5.0, 5.0, 5.0, and 2.35 for

electoral process and pluralism, functioning of government, political participation,

political culture and civil liberties respectively, is ahead only 4 rows from countries

classified as authoritarian regimes (The Economist Intelligence Unit Report, 2018).

Following the flawed democracies in the list, hybrid regimes, which are positioned as

third group countries, present intense political pressure on the opposition; political

elections are not established in a fair and free way; corruption is widespread; rule of

law and civil society is weak; judiciary is not independent and pressure and

The European Union targets Turkey due to similar reasons in 2018 EU-Turkey

Progress Report. In every chapter except for the one focusing on Turkey’s refugee

policy, Turkey does not perform desirable developments. Especially under the state

of emergency after the attempted coup in 2016, the country has experienced a sharp

decrease in areas such as democracy, freedom of thought and expression, human

rights and so forth. Elections are criticized intensely in the report and in international

media by the fact that they fall short of international standards and do not provide

equal campaign opportunities and equal representation on media for each parties

(OSCE and PACE Elections Monitoring Reports).

Reflecting on the previous EU progress reports, Işıl Türkan, in her 2012 article,

criticizes press freedom in Turkey. Despite many democratization steps towards

becoming a member of the EU in the first years of AKP rule, Türkan (2012) states,

freedom of expression and press did not have its share in this development. “Free

speech is now in a state reminiscent of the days before EU accession talks.

Journalists or academics who speak out against state institutions are subject to

prosecution under aegis of loophole laws” (Fulton, 2008). According to the

Economist (Democracy Index, 2019), Turkey leads the world in jailed journalists.

The Economist says, Turkey is among the group of governments, (China, Egypt, Eritrea and Saudi Arabia) which are “the most censorious governments follow a

familiar pattern of suppressing the media and locking up dissenters” . . . “for 70% of

all reporters that were imprisoned last year, mostly for infractions against the regime.

Of the 172 reporters being held in those countries, 163 were detained without charge

Under such circumstances, in Turkey, each election is just another indicator

signifying that the country is a hybrid regime. Berk Esen and Şebnem Gümüşçü

(2016), in their work assessing Turkish democracy, states that Turkey experienced a

dual regime change under the AKP government. With AKP Turkish political tutelage

was replaced by the rising competitive authoritarianism. According to their findings

on the analysis of 2015 elections cycles and Turkish political trends, elections in

Turkey are unfair, civil liberties suffered a systematic deterioration and that AKP is

in a disproportionately advantageous position in the elections. What happens in and

after the election in 2015 are the indicators that the country has become more and

more authoritarian. And in fact, with several elections and nondemocratic practices

that narrowing down the legal channels for the opposition in the country together

shows that Turkey’s political regime is a proper example of competitive

authoritarianism, and AKP institutionalizes this type of regime in the country for

many years (Çalışkan, 2018).

The continuity of hybrid regimes depends on the ability of the government to defeat

the opposition and the lack of interaction between the opposition and the citizens

(Ekman, 2009). Considering AKP’s domination over state apparatus and media,

AKP leaves no room for opposition to form an interactive relation with citizens and

have a chance to experience political change. My findings also exemplify this

situation where some dissidents voted for the opposition not because of their

sympathy for the party but because they felt they had no alternative and they cry out

Political polarization in Turkey is a fact and it harms Turkish democracy as well.

According to McCoy, Rahman and Somer (2018) polarization is “a process whereby

the normal multiplicity of differences in a society increasingly align along a single

dimension and people increasingly perceive and describe politics and society in terms of ‘Us’ versus ‘Them.’” This is exactly what has happened in Turkey in

election periods. Especially in last elections, politicians led by the President of

Turkey and AKP Chairman Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and MHP (Nationalist Movement

Party) leader Devlet Bahçeli explicitly declared that Turkey is divided between “us”

Cumhur İttifakı (People’s Alliance) and “them” Zillet İttifakı3

. On 27 February 2019,

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan posts a picture on his Twitter account under his tweet stated as follows: “Turkey nowadays has two major alliances against each other.” (Bugün

Türkiye'de iki ittifak karşı karşıyadır.)

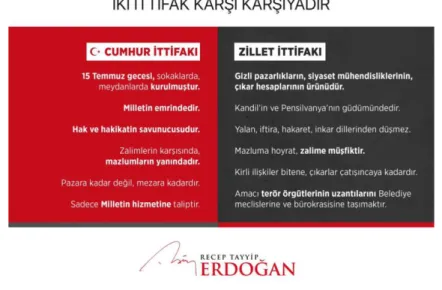

Figure 1. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s tweet (Data from Twitter) (2019)

Although there are numerous similar statements like this one, I believe this one

summarizes all of them perfectly. The President of Turkey and his followers used

quite polarizing language during election campaigns. According to them, the true

owner of the country is Cumhur İttifakı, AKP and MHP alliance, and only they serve

for the goodness of the country. According to Erdoğan and his supporters, others, namely Zillet İttifakı (referring Millet İttifakı, which is CHP and İYİ Parti (Good

Party) alliance) are the ones working with the terrorist organizations such as PKK

and FETO. This is I believe a perfect demonstration of how Turkey is polarized by

the state authorities itself. As stated by McCoy, Rahman and Somer (2018),

polarization makes democracies vulnerable with declining respect for

counterargument, decreasing possibility of consultation with others and intense

democratic erosion, and Turkey is one the prominent examples regarding these

issues. However, existence of polarization seems to be perceived differently among polarized groups in Turkey. Participants of Düzgit and Balta’s study who were

“members or supporters of the opposition parties” pointed to empirical evidence and

complained about polarization as “the most critical issue for Turkey,” while

pro-AKP participants denied its existence and some of them attributed the discussion about polarization to “foreign and media provocation” (Aydın-Düzgit & Balta,

2017).

These political features of the country leave no room for dissidents in Turkey. “Because, for the most part, a broad consensus among both the elites and the mass

public to uphold democracy as the only viable system of rule is lacking, hybrid

regimes tend to be either unstable, or unpredictable, or both” (Levitsky and Way,

electoral behavior. At the end, the chance or possibility for dissidents to change the

political system in Turkey is not likely as they believe, and as Adam Przeworski

(1991) states what makes a system democracy is the ‘institutionalized uncertainty.’

In a democracy, “all outcomes are in principle unknown and are open to contest

among key players (e.g. who will win an electoral contest or what policies will be

enacted). The only certainty is that such outcomes will be determined within the

framework of pre- established democratic rules” (Menocal, Fritz and Rakner, 2008).

In other words, “the democratic process needs to be viewed as the only legitimate

means to gain power and to channel/process demands” (Menocal et al., 2008). This is

what Turkish democracy lacks, and that is one of the reasons of dissidents on their

initial statement regarding not attending elections. Dissidents feel like their vote does

not matter and will not change anything, so why should they vote?

Maybe they should not. However, as I stated earlier, they do. Dissidents in Turkey

vote no matter how they think at the first place after an election. According to wide

range of political scientists, hybrid regimes are to be named under different terms

such as competitive authoritarianism, electoral authoritarianism,

semi-authoritarianism, semi-democracy, electoral democracy, partly-free democracy,

illiberal democracy, virtual democracy, soft authoritarianism, pseudo-democracy. All

of these concepts intersect at the electoral component. No matter how the system or

the elections is corrupt or unreliable, people with different proportions in different

countries cast their votes in elections. That, I believe, makes voting more meaningful

for people than it is just a common way of political participation. In our case,

dissidents in Turkey cast their vote because of several factors including political,

the elections. Therefore, this thesis reveals different peculiarities of voting behavior

among dissidents in Turkey. By explaining the factors behind voting behaviors of the

dissidents, this thesis attempts to solve the puzzle of why dissidents vote despite that

they said they would not. This thesis fills a gap in the literature by showing that the

political factors in particular, social and psychological factors play a significant role

in convincing dissidents to vote despite their negative stance against voting, while

other works focus only on factors which led people voting at the first place. This

thesis takes a step further and contributes to the literature by scrutinizing the voting

CHAPTER II

SOCIAL MEDIA AS A SOCIAL SPHERE: WHY TWITTER AND

EKŞİ SÖZLÜK?

Under such an environment in the country as I reflected in previous pages, a

sophisticated type of voting behavior among dissidents arose. Especially within last

two years, a significant number of dissident voters began to state that they “will not

vote anymore” referring prospective political elections. However, not only are there

no significant decreases in the election turnouts in Turkish elections -especially after

2017-4, but also, as I will show, many dissidents who first stated on online websites

that they will abstain, later on stated that they actually voted after all. Such act

repeated before and after every election in this couple of years. In this thesis, I

elaborated on this specific behavior among dissidents, who are generally CHP and

HDP supporters.5 In order to do that, I analyzed these voters’ tweets on Twitter and

4 See Appendix A.

5 There is no spesific number accordingly with this argument (since neither Ekşi Sözlük nor Twitter

provides statistics), yet as it is seen in the data analysis part of the thesis most of the posts were shared by CHP or HDP supporters.

entries on Ekşi Sözlük. There are two main reasons why I preferred to get my data

from such platforms on social media. First, I embrace the idea that social media is a

public sphere.

Twitter and Ekşi Sözlük within social media environment bring people from

different backgrounds and provides for them instant and constant connection and

communication. People share their thoughts, moments, lives with each other. That, I

believe, is not different socializing in the concrete public spaces6. Actually, to be

fair, social media nowadays is much more of a public sphere than a café, a restaurant,

streets, squares, schools, work places, and so on. Public is online every time and

parts of it are interacting with one another continuously (Rasmussen, 2014; see also,

Hill and Hughes, 1998; Holt, 2004; Raphael and Karpowitz, 2013; Dahlgren, 2005;

Dahlgren and Olsson, 2007; Nie and Erbring, 2000). And, thus, data is enormously

large and various for my research. Second, due to environmental features of the

country politics people are afraid of expressing their views on political matters

especially if they are against the government. Adding to that it is already not easy for

people to answer a stranger’s questions, answering questions on political matters for

an interview is not likely to happen in a country where freedom of thought and

expression is imprisoned. Therefore, I head for social media to seek for answers to

my questions.

The internet and the social media are ubiquitous. According to Statista (2019),

almost 4.4 billion people were active internet users as of April 2019, encompassing

58 percent of the global population. Twitter as a social networking and

blogging service has averaged at 330 million monthly active users, while 8.6 million

people in Turkey, nearly 10% of the population, use Twitter. It enables users to read

and post short messages, which are called tweets. Tweets are limited to 280

characters and users are also able to share photos or short videos. Tweets can be

posted publicly or to followers who are allowed by the users. Twitter is also an

important communication channel for governments and heads of state - former US

President Barack Obama claimed a runaway first place in terms of Twitter followers,

with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan ranking second and third, respectively.

Ekşi Sözlük with its 115,853 users is a collaborative hypertext "dictionary" based on

the concept of websites built up on user contribution. Ekşi Sözlük gets 35 million

monthly hits and that makes it one of the 300 most visited websites in the world (Ekşi Sözlük, 2019). “As an online public sphere, Ekşi Sözlük is not only utilized by

thousands for information sharing on various topics ranging from scientific subjects

to everyday life issues, but also used as a virtual socio-political community to communicate disputed political contents and to share personal views” (Hatice Akça,

2005).

Before going further on the findings that I gathered from Twitter and Ekşi Sözlük, I

will address social media in manifold aspects in terms of its relation with politics. As

I stated earlier, social media is a public sphere. According to Habermas, an ideal

public sphere is a place where private people came together and discuss and consume

facilitated through the use of printed media (Baker, 1994). Analogically, Alexis de Tocqueville states that “Only a newspaper can put the same thought at the same time

before a thousand readers.” Since technology evolved significantly and

revolutionized people’s lives, printed media and newspapers yield to social media

presenting an instant publicity in the words of Kierkegaard. This change produces and reproduces a reciprocal relationship between social media and people’s lives.

Not only people shape social media by creating and spreading content but also social

media shapes people by creating audiences whom are open to any kind of interaction

out of them (Compaine and Gomery, 2000).

In a comprehensive research on Twitter as one of the dominant social media

platforms, Murthy (2012) uses the term, experience of society, to explain that social

media provides a societal experience by giving people a possibility for hearing the

voices and thoughts of ordinary people. In this way, he claims, Twitter serves as a

democratizing tool along with being a social area. As Murthy states, Twitter, which

is one of the leading channels of the internet world, is one of the ways of people use to say others that “I wish to speak with you”. Such communication inevitably results

in some social behaviors rooted in social media on various political issues. Arab

Spring, Occupy Movement, Gezi Park Movement are among protests sprung out of

social reactions emanated from social media through a spontaneous and snowballing

development, and they changed countries politics and the way people look at politics

everlastingly.

Due to elements mentioned above it is needless to say the social media and internet

disciplines, especially for political scientists. One of them, Dimaggio (2001), claims

that the Internet creates a less behavioral cost7 in creating an informed and engaged

public. This information and engagement, however, does not always lead to peaceful

environments. The dissemination of hate speech and extreme views, for instance,

may increase with the encouragement of anonymity that the internet provides.

According to another study uses World Values Survey on East and Southeast Asia,

the Internet as an alternative source of information for citizens strengthens marginal

within the traditional political communication system while becoming an

intermediary of civil society outside of traditional politics (Lee, 2018).

Given that it has such a strong structure; it is inevitable for the state to control the

social media and internet. This control can be direct or indirect. Either way in

Turkey, social media and internet is controlled and censored. The government

implements strict controls for news sources on the Internet and ensures that the news

is transmitted in the desired ways (The situation of freedom of thought and

expression in the country was mentioned in the first chapter). However, in countries

where the state is the biggest media mogul, controls news feed and content, and

manipulates them, citizens found to be politically more “ignorant and apathetic”. On

the other hand, where media control is less, citizens are politically more

knowledgeable and active (Leeson, 2008).The menu of actions available to cyber

activists for online mobilization depends on the regime type because coercive

measures used by nondemocratic governments narrow down the range of available

options and make online mobilization more costly (Tkacheva, 2013). On the other

side, for more democratic countries social media functions as a boost for turnout

rates in political elections by enabling people to gather information easily (Tolbert

and McNeal, 2003).

The majority of Internet users, however, reside in countries that restrict the freedom

to assemble, freedom of thought and expression and right to vote.8 This swift

expansion of the Internet in countries which people’s rights restricted brought about

the discussion over whether new technologies meaning internet/social media has a

democratizing potential or not. Some academics perceive the Internet as a nostrum

for political repression (Clay, 2008; Howard, 2010). Others, to the contrary,

represent the Internet as a tool capable of strengthening nondemocratic rulers

(Morozov, 2011).

Tkacheva (2013) raises the question “When and how does online activism can

transform political space?” to illuminate on the issue of the relationship between the

Internet and democratization by scrutinizing the complex interaction between virtual

and offline communities. According to her findings, cyber activists have a remote

impact on political space since they are not likely to establish a bond with people in

real life due to lack of repeated social interactions, yet they are good at spreading

news and molding public opinion. However, in countries that people have strong ties

with each other already and uses internet widely, dissemination of information and

ties between people enables expansion of political space.That is, I believe, is the

case with Turkish people, since people in Turkey are in close relations with each

other socially and uses social media very effectively in terms of spreading news and

forming public opinion.

8 China has the largest number of Internet users in the world by far, although large non-democratic

Social media is not only a place to ordinary citizens for sure. Since it is a public

sphere, politicians also use social media platforms frequently. Hence, it is now way

easier, faster and more effortless for citizens to connect with politicians through

social media and vice versa. Donald Trump, the president of the United States of

America, is one the politicians using Twitter quite actively. By analyzing The President’s tweets Gounari (2018) argues that Twitter as a public realm is

normalizing racist and nationalist discourses. As she claims regime of the American country has turned into authoritarianism after Donald Trump’s elected as the

president and thus Twitter is seen as the trademark of the “US style

Authoritarianism”. Twitter, in this context, functions as an instrument of discourse

production, reorientation and social control of social media. From these perspectives

I also see Twitter as such an instrument and my thesis is an attempt to analyze dissidents’ discourse on the social media.

CHAPTER III

THEORETICAL AND METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK

According to Brady, Verba, and Schlozman (1994) people do not participate in

politics due to three reasons: they cannot, they do not want to, or nobody asked them to. ‘They cannot’ participate because they do not have time, money, or civic skills.

‘They do not’ participate since they are not interested in politics. Finally, ‘nobody

asked them to’ participate because they are isolated from the society. Voting,

according to Brady et al., is mostly driven by interest. Civic skills like education also

matter. In accordance with this classification, dissidents in Turkey decide not to vote

since they do not want to be interested in politics any more. However, there is a

highly interested voting behavior lies behind such action. Voting for these people is a

loaded political act, and yet never worked for their good, therefore they lost their

hope. Additionally, not being interested is a reason for abstention from politics in

Brady et al. argument, whereas it is the consequence of not being able to make use of

voting behavior for dissidents in Turkey. In this sense, initial decisions of dissidents

regarding abstention adds on Brady et al. classification by providing a sophisticated side of ‘not interested’ to participate in politics. For the final act of dissidents in

Turkey, namely voting in elections, dissidents represent a complete example of that ‘they can’ participate in politics, they are forced to be ‘interested’ by several factors

and thus they were ‘asked to’ vote in the elections.

Explanations of boycotting elections focus mostly on electoral factors. One strand

sees electoral boycotts as sincere steps to protest the unfairness of the electoral

process (Beaulieu, 2014; Bratton, 1998; Lindberg, 2006 and 2009). Furthermore, “a

broad criteria identifying conditions that might be reasons to abstain: illegitimacy and unfairness” (Hanna, 2009). “Electoral considerations may do an exceptional job

of explaining differences between authoritarian and non-authoritarian countries, but

are weaker when it comes to explaining the variation in opposition strategy across authoritarian regimes, and within a single authoritarian country across elections”

(Buttorff and Dion, 2016). Opposition parties in such regimes consistently question

the legitimacy of the elections, always object to the electoral process by the claim

that the elections are manipulated, and mostly expect to lose the election. And, “yet not all authoritarian elections are boycotted. Among authoritarian elections held between 1990 and 2008, 20% of legislative elections and 16% of presidential elections were boycotted by at least one opposition party, leaving a large number of cases where the opposition decided to participate despite the apparent electoral incentives to boycott” (Buttorff, 2011).

Moreover, the decision to participate or boycott is far from constant within

authoritarian countries (Schedler, 2009; Weeks, 2013). Turkey, as a hybrid regime,

also shares the same destiny. Boycotting the elections is not a widely common or

even rarely action by the opposition, although they question the system. However,

lately such words started to be spoken out loud. Dissidents after each and every

election starting from 2017 began to articulate the possibility of

ended up at the polls, although they stated after elections that they would never vote

again.

In this thesis, to understand what accounts for turnout among dissidents in Turkey, I

divided the question into two pieces: “What did make people say that they will not

vote again?” and “what did affect them so that they changed their minds and acted oppositely?” Although the questions are separate, answers are interlinked by the

people in their tweets on Twitter and entries on Ekşi Sözlük. I used first sub-question

to identify my sample group, who are the dissidents intended to stay away from

elections. Second sub-question, on the other side, shows us the answer of what

actually convinced people who did not want to vote. To reach out these answers,

mainly in the form of tweets and entries, I searched for specific wordings on Twitter and Ekşi Sözlük platforms.

I searched for 18 relevant words and sentences on Twitter. Since people do not

always use proper forms of wordings I added deformed versions as well. Out of these

18 searches I had to deal with tweets without numbers. Twitter does not provide for

the actual number of the tweets between certain dates, since one particular tweet can

be a continuation of another and that can be a mention to another tweet and that can

go on as such. This makes it harder to count the number of results. In the file

enclosed9, links of each and every wording search and topic is available. Out of 18

searches I specified 650 tweets from different people and conducted a discourse

analysis on them for the purpose of my thesis.

Wording searches on Twitter between 01.01.2017 and 19.06.2019 are as follows:

-oy (vote) -seçim (election) -sandık (ballot box) -boykot (boycott)

-oy kullanmayacağım (I will not vote) -oy vermiyorum (I am not going to vote) -oy verdim (I cast my vote)

-oy vermeyeceğim dedim (I said that I would not vote) -yine oy verdim (I voted again)

-oy verin (Vote!)

-oy vermeyecektim (I was not going to vote)

-oy vermicektim10 (I was not going to vote)

-boykottan vazgeçtim (I gave up on boycott) -boykot edecektim (I was going to boycott)

-boykot edicektim11 (I was going to boycott)

-oy vermeyi düşünmüyordum (I was not thinking of voting)

-oy vermeyi düşünmüyodum12 (I was not thinking of voting)

-oy kullanmayacaktım (I was not going to cast my vote)

In the Ekşi Sözlük platform, I analyzed 884 pages of entries of which the total

number is 8604 entries. I selected 100 entries out of these entries and analyzed them

for the purpose of this work. Most of these entries, however, functions differently in

regards to my questions. They show what might have affected dissidents and brought

them to vote can also be because of oppression they experienced through social

media. In this sense, entries on Ekşi Sözlük serve differently than tweets on Twitter.

I will comb through that later in the relevant chapter.

Topic searches on Ekşi Sözlük are as follows:

10 Deformed version 11

Deformed version

-23 Haziran 2019 Sandığa Gitmeyecek Yazarlar (23 June 2019-Users who will not vote)

-31 Mart 2019 Sandığa Gitmeyecek Yazarlar (31 March 2019- Users who will not vote)

-31 Mart 2019 Sandığa Gitmeyen Yazarlar (31 March 2019- Users who did not vote)

-24 Haziran 2018 Oy Kullanmıyoruz Protestosu (24 June 2018- We Protest Voting)

-Sandığa Gitmiyoruz Kampanyası (Anti-vote movement)

-Sandığa Gitmeyen Yazarlar ve Nedenleri (Users who did not vote and their reasons)

-Sandığa Gitmeyen Kesim (Those who did not vote)

-24 Haziran’da Sandığa Gitmeyecek Sözlük Yazarları (Users who will not vote on 24 June)

-Mart 2019’da Sandığa Gitmeyecek Muhalif (Dissidents, who will not vote on March, 2019)

-Adam gibi tıpış tıpış sandığa gideceksiniz (You will go willy-nilly to vote) -Seçimde Oy Kullanmayan İnsanın Amacı (Purpose of the person who did not vote)

-Seçimlerde Oy Kullanmayan Geri Zekâlı Orospu Çocuğu (Idiot and son of a bitch user who did not vote)

-Seçim Boykotu Sayesinde İstediğini Elde Etmek (Getting what is wanted thanks to boycott)

-Yenilenen İstanbul Seçimini Boykot Etmek (Boycotting the rerun Istanbul election)

-boykot-sine-i-millet-sivil-itaatsizlik (boycott- withdrawal from the parliament-civil disobedience)

-Boykot (Boycott)

-Oy Vermemek (Not voting) -Oy vermiyorum (I will not vote)

-Oy Kullanmayan İnsanlar (People who do not vote)

-2 Nisan 2017 Referandumda Oy Kullanmayacaklar (Those who will not vote on 2 April 2017)

-Referandumu Boykot Eden Yüzde 7’lik Kesim (7%-Those who boycott the Referendum)

-Oy verme (Do not vote!)

-17 Haziran 2019 TKP’nin İstanbul Seçimi Kararı (17 June 2019 TKP’s verdict regarding Istanbul election)

-Sandığa Gitmeyenlerin 52’sinin CHP’li olması (52% of those who do not vote are CHP supporters)

-Seçimleri Boykot Etmek (Boycotting elections) -Oy Vermemek için Nedenler (Reasons not to vote)

-Oy Vermemek ile Boş Oy Vermek Arasındaki Fark (Difference between not voting and invalid voting)

-Oyumu boşa atıyorum çünkü (I will cast an invalid vote because…) -Oy kullanmayacağım (I will not cast my vote)

-Oy Kullanmanın Hiçbir İşe Yaramaması (The fact that there is no good use of voting)

-Oy Vermeyecek Yazarlar ve Destekledikleri Parti (Those who will not vote and the political parties they support)

-Oy Vermeyecek Olmanın Dayanılmaz Hafifliği (Unbearable lightness of not casting vote)

-Oy Vermeyeceklere Ufak Hatırlatmalar (Little reminders for those who will not vote)

-Sandığa Gitmeyecek Yazarlara Duyuru (Notice for users who will not vote) -Seçimlerin Formalite İcabı Yapılması (Elections without choice)

Since I searched for specific words in order to see why dissidents in Turkey voted in

every election despite their contrary statements, and I tried to capture the meaning of

their words and sentences in a critical way, this thesis is an example of discourse

analysis. To capture the factors/reasons/motives driving people vote, I examined

every tweet and entry they shared on Twitter and Ekşi Sözlük under the listed

wording searches and topics above. I have selected 650 tweets13 and 100 entries14 as

a sample for this thesis. As a result of my examination over these data, 3 main

themes appeared over the reasons of dissidents regarding my thesis questions. First,

most of the dissidents who stated that they would not vote anymore after an election

and still ended up at the ballot box for the next election attributed such behavior to

political factors in the country. Tense and hostile political atmosphere constituted by

mainly AKP and MHP politicians and the partisan media, and inclusive rhetoric used

by mainly opposition candidates and opposition partisanship are components of this

theme depicting why dissidents voted. Second, there are social factors such as

pressure coming from family, friends and surrounding circles around people drew

13

See Appendix B.

them to the ballot boxes. Third, numerous psychological factors such as inner

conscience and hope played an important role in making dissidents vote.

It is important to point out that all of the factors are in fact in relation with each

other. Indeed, it would be wrong and senseless to claim that these factors are solely influential over people’s decisions and actions. However, for the sake of this

scientific research and in order to make the arguments in this thesis clearer and

comprehensible, I focused on the commonalities of different statements. Thus, out of

these commonalities 3 main themes (political, social, psychological) came to

existence. In following parts, I will focus on prominent examples of statements

which are representing many similar tweets and summarizing them with regards to

my thesis questions.

1. Political Factors

Under this theme, major reasons convinced dissidents to vote in the elections despite

their statements after previous election are analyzed in 2 parts. First part, which I will

address as political atmosphere, contains dissidents who stated that they wanted to

react against the unrighteous, covert and black propaganda and discriminating,

polarizing and hostile political attitude and discourse by the politicians of the ruling

party AKP, its ally MHP and the partisan media which is under the control of the

government. Second part, named as political figures, involves politicians and

political parties that had an impact on the dissidents and made them vote no matter

A. Political Atmosphere

Political atmosphere in Turkey is confined with polarization, black propaganda,

hostile use of political discourse towards certain group of voters, namely opposition.

Although such atmosphere harms Turkish democracy, voter turnout in the elections

does not vary substantially. In fact, what Dodson (2010) claims regarding that

polarization plays an interesting role in reinforcing turnout in the elections is true for

the Turkish case. Dissidents who proclaim not to vote at first and ends up at the

ballot box also verify this argument. My findings reject Morris Fiorina’s (2006) ideas

pointing out that polarization turns off voters and reduces electoral turnout. Instead, they withstand Anthony Downs’ (1957) rational choice theory of turnout:

“polarization energizes voters and stimulates participation.” Lawrence (2016)

temporal analysis on 12 democracies over the period 1976-2011 reveals a pattern

which is in line with my findings: “over-time increases in citizens’ satisfaction with

democracy are associated with significant decreases in voter turnout in national

elections.” Dissidents in Turkey are also highly dissatisfied with the country’s

democracy; in fact, this is one of their motivations to vote. How bad the country gets

dissidents seem to react against it, and polls are the last and only places for them to

do so.

[1]15 Armağan Çağlayan, as a well-known TV personality and lawyer in

Turkey, tweeted on 14 March 2019:

“I was not thinking of voting. But they managed to get me to

the polls with the propaganda method they used. I will vote.”

This tweet got 17,000 likes and nearly 2,000 retweets within hours, and it shows that

there are thousands of people agree on this specific statement. There are also

hundreds of responses to this particular tweet most of which saying that they are sharing the same thought. The critical part of this sentence is that “…they managed

to get me to the polls with the propaganda method used.” There are many tweets like

this, yet as I stated earlier I here present the ones summarizing and representing the

similar group of statements. Dissidents who express similar kind of thoughts voted in

order to show reaction to unrighteous, covert and black propaganda which was led by

the partisan media owned by the government. Dissidents wanted to stand together

against the discriminating, polarizing and hostile political attıtude and discourse used

by the prominent politicians like the president of Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli, Minister of Internal Affairs Süleyman Soylu, Former

Mayor of Ankara Melih Gökçek and many others in AKP and MHP. So, these

politicians and partisan media are “they” in Çağlayan’s tweet. And, they are the ones

who “managed to get people to the polls” and increased the turnout rates.

[2] One of the responses to Çağlayan’s tweet:

“They are so low; I want to intervene.”

Here again a dissident voter expresses the “urge to intervene” because he “cannot

stand the worthlessness of ‘them’”. As this tweet shows, people feel like they have to give reaction to such “worthless” attitudes and voting is the only possible way to do

[3] An entry on Ekşi Sözlük:

“(see: mart 2019'da sandığa gitmeyecek muhalif/@pablo

andres)16

(See: 31 mart 2019 sandığa gitmeyecek yazarlar/@pablo

andres)17

I explained the reasons why I would not go to the polls with

two long articles above. I told you there was no good use to cast one’s vote; I am not going to write them down again.

I want to say I have changed my mind without even hesitating

about it. Yes, I am still behind what I have said in both

writings, but we have witnessed all that rudeness, so rude, so

naughty, so hypocritical, and so disgusting. There is no direct

damage, and I am not changing my mind. But, no mercy! I feel

sick. I'm sick of your YouTube ads, your TV channels

constantly making propaganda on the ground, your lies,

slanders, and your dirty language.

You convinced me, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. I certainly would

not have voted, but you and your men have done so many

things. I don't like the party or the candidate I'm going to vote

for, but I hate you, hate you. It is enough.”

16

Reference to other posts of the user

In the case of Abramowitz and Stone’s work (2006) on the 2004 presidential election in the USA, the main reason for the increased turnout was “the intense polarization

of the American electorate over George W. Bush.” According to writers, Americans

went to the polls in order to express how they felt about Bush, who was the most

polarizing presidential candidate in modern political history. Similarly, dissidents in

Turkey also went to polls in order to show their hatred towards the AKP leader and

his followers. Just like Americans who either loved Bush or hated him, dissidents

went to the polls to express their feelings, namely and mostly hatred, towards Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. If it was not for him, turnout would be lower, according to dissident

voters.

‘See’s given in the beginning of the entry above explains why the owner of the entry

would have not gone to vote, and mainly states that he was a voter for CHP for many

years and he thinks that mainly CHP with other opposition parties in general are as

much degenerated and undemocratically governed as AKP. Thus, none of these

parties deserves his vote no more. However, although he still thinks exactly same

with his previous thoughts, he says that Erdoğan and “his men” convinced him with

limitless shamelessness, impudence, shiftiness, hypocrisy and so forth. Anger seems

to be mobilizing by increasing participatory intentions and factors related to

participate (Weber, 2013). Thus, we can say that his vote is one of “Enough!” votes.

[4] A tweet posted before 31 March 2019-Local Elections:

“It was a fact that I was not going to vote until I saw those who

were so unfair, deceitful, full of threats, blackmails, slanders,

squares and saying ‘I did not say so’. Loathed. Ran out of my patience. Therefore, I changed my decision. I voted.”

This one is particularly important tweet for its explanatory content. Dissidents changed their mind and voted since they are “browned off injustice, deceitfulness,

insults (to the people), threats, blackmail, slanders, dirty games, denying what has been said on the streets”. Although, she said she would never vote again, such factors

she listed made her vote at the elections. Here again we see polarization caused by

AKP and its supporters energizes dissidents and made them vote.

[5] Tweet

“With all my sincerity I say; if they did not use such a harsh

style and insult people with words like ‘Zillet’, I had promised

that as long as Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu is the party leader, I would

not have voted for CHP. They forcibly took me to the polls!

I'm guessing there are too many voters like me in this matter.”

This dissident states that he is actually against the leader of CHP, party which he

normally supports and yet the reason of he decided not to vote for in the elections.

He no matter what voted in the election, because “‘they’ used a language hard to ignore” and that “forcefully” brought him to the polls.

[6] Tweets

“It is election day now. We are all upset, we are all sorry

Twitter) that I would not vote. I was wrong; we should not

hand over the rule of this country to them. Tomorrow I will

vote for İmamoğlu18

. You also have to vote; this is what is

necessary. Do not give up!”

“I was never going to vote. I was so determined. The slanders

and ugliness in this election campaign were enough for me to

understand my mistake.”

Entry

On not-voting behavior:

“One of them was supposed to be me. After the referendum, I

decided not to vote for the rest of my life. I did not use it in the

last election. But the AKP's mudslinging campaign in this

election period, dirty politics had my tongue-tied. I will be

directly going to vote at 8 in the morning for Mansur Yavaş19,

and it is just because of the rage they caused.”

In this couple of tweets and an entry, we see that voters are resentful and sad over the

24 June elections and referendum results20 and therefore they would never be going

to vote again. However, because they did not want to hand over the “country’s rule” to “them” and to cleanse the Augean stables voted in the elections. Voting is seen as

the “necessity” in order not to give up on the homeland. What has been done and

18 CHP’s mayoral candidate for Istanbul in 31 March 2019 and 23 June 2019 political elections 19

CHP’s mayoral candidate for Ankara in 31 March 2019 political elections

said on the way to elections bursts people with anger and fury, which in turn

accelerates turnout rates.

[7] Tweets

“Hitting Mansur Yavaş below the belt, lies about shutting the

prayer calls up, Yeni Akit thing, other garbage media news...

Bravo you! You have consolidated the opposition wing. I was not going vote, but I am going to vote now.”

“I was not thinking of voting. But they managed to get me to

the polls with the propaganda method used. I will vote.”

“Reverse consolidation. I am in the same situation.

Despite the deplorable administration of the CHP...”

First tweet touches upon the situation of partisan media which “lies” and create fake

news. According to voter, such “rubbish” news and lies “consolidated the

opposition” and made them vote in the elections. Another one demonstrates that

people were “reversely consolidated” by the propaganda method used by the AKP

notwithstanding CHP’s undesired administration. Not only politicians but also

supporters of AKP and its media moguls contributed to the polarized

environment, and this in turn affects dissidents and leads them to cast their vote.

[8] Tweets

“I was not planning to vote before there were aggressive

(İnsanın en hassas yerlerini kaşıyorlar.) I'm going to vote

because of many things, for example Yavaş, azan-whistling

lies. It is seriously weird though. If they had just shut up, CHP would take away the voters from the ballot box anyway.”

“I was going to boycott the elections. Thank you AKP, you

convinced me to vote for the CHP. Again.”

“If they did not resort to the arrogant campaign language of

defamation, humiliation and insulting the opposition, a

serious part of the opposition voters would not go to the

polls and they would win the election without an effort. So

it's fortunate that some things are stumbling on their own

when the time comes :D”

“I was going to boycott this election, but they

insulted so much that I went to the polls unwillingly

because even one vote is very important. Not only me

but also my parents were going to boycott it. We all

voted at the end of the day.”

Entry

“(See: #78509627 #78549866) I had stated here in these

articles that I would not go to vote. I even swore at myself

threating opposition with imprisonment was the last straw

for me. I voted with a last-minute decision. If I had not, I

would definitely regret the results. It is not Kılıçdaroğlu or

the current CHP administration that made me vote, but the AKP itself, especially Erdoğan and Süleyman Soylu.”

These series of tweets and entry show how AKP and its supporters made people vote

against themselves. According to voters, if they did not speak at all, CHP would

already put dissidents away just by itself. These are some of many tweets saying that

AKP created his own enemy through a hostile and polarizing discourse and it at the

end served for the opposition party. People who were actually former CHP voters

and stated that they would not vote for CHP for all the political mistakes the party

made voted exactly for CHP candidate thanks to AKP and its repelling propaganda.

In other words, CHP candidate does not seem to win the elections, rather AKP lost it

with all the effort convincing dissidents to vote against itself.

[9] Tweet

“Seriously, as an HDP supporter I was not going to vote. I was

mad at the CHP candidate. However, after this repulsive

election propaganda by Erdoğan, I would have suffered a

lifetime of remorse (vicdan azabı) if I did not vote against them.”

Here a HDP supporter states that although he is mad at CHP candidate, he would “feel guilty and full of remorse” unless he votes against Erdoğan’s “repulsive”

propaganda. Such feeling evoked by the Erdoğan and his supporters made dissident

people vote despite their earlier statements which would actually help Erdoğan to

win without any effort.

[10] Tweets

“I also object wrongdoings. I can assure you that I am not

blindly tied to CHP or anything. I was not going to vote either

after all CHP chairman thing, however I deeply resent shabby

slanders by AKP politicians, economic conditions, financial

difficulties, president and ministers shouting out in the streets, “tanzim kuyrukları”, increasing prices, widening income gap

between poor and rich and so on. Thus I feel like I have to take

a stand against all of these.”

These tweets advert another factor affecting the voter and forcing him to vote.

Along with economic hardship, the president and ministers shouting out in the streets with full of worthless slanders made people feel like they “have to react”. Like many

similar tweets this one demonstrates again that dissidents decided not to vote since

they had problems with opposition party rule, and voted anyway since they have

problems with the government party rule.

[11] Tweet

“I was not going to vote, but I will vote out of spite now. I

Entries

On non-voting behavior:

“Those who say ‘I will not vote’ are probably the İYİ Party

and CHP supporters. I said, ‘Damn, I will not vote anymore’

in the last election, but this is what they wanted: to

intimidate and discourage. I do not love opposition parties. I

even started to swear at them at the moment I saw them on TV. Especially I am so sick of Kılıçdaroğlu sounds like a

broken record saying the exact same things for the last 5

years. It is sixth of one and half a dozen of the other. They

are all incompetent. But because I hate other political parties

to death, I am going to vote for CHP again. I do not want to

see people on TV who grin like a Cheshire cat. At least the

results should be approximate so that others do not spout off

about that. We better be content with what we have now. So,

vote and make other people vote.”

“A while ago, I stated my opinion here [# 87027561], and

despite my friends who tried really hard to convince me, I

said my decision was final (about not voting in the

elections). Big talk!

Let put the country aside, as I see what has been done to Mansur Yavaş and Imamoğlu it makes me want to vote so

badly despite those dumb Kılıçdaroğlu and Armenian-fan

Canan.

Yes, I know he cannot win in Istanbul and my vote will be

plus point for the clumsy Kılıçdaroğlu and (örgütçü) Canan

unfortunately, I am deeply in sorrow because all of these,

but still we should show our true colors.

Of course, my respect for those who will not vote due to all

the happenings is endless.”

“Let me be clear; I had no intention of voting either. It was

not because our vote was good-for-nothing. I decided not to

vote since I did not want to provide the legitimacy that the

system acquires from our votes; this legitimacy is the source

of immorality in the country. When I do not vote, they will

stew in their own justice. First, I got so pissed off at Sarıgül.

Then, the ugly campaign carried out by the ruling party and

its allies with the love of authority (koltuk aşkı) disgusted

me. Now I am going to the ballot box just to show where I

stand. Do I love candidates or other political parties? No.

Am I hopeful? I am not. 7.5% of the people who voted

against the Evren’s constitution were neither satisfied nor

hopeful either. When the era changed, 92.5% denied their

vote and claimed to be one of the 7.5% of the voters. So, I

will go to the ballot box in this nonsense system, which they

People are unimaginably polarized in the country. Dissidents, who claimed not to

vote and yet did so, voted most of the time just to spite and just to take a stand

against the AKP and its supporters. Here voters say that they despise CHP, but

they despise AKP “even more”. Their whole purpose to take sides with CHP is

just to be against AKP.

[12] Tweets

An AKP supporter tweets: “You will get 52% of the votes.

You will get 24 of 39 districts in Istanbul and lose the

metropolitan. You will get 22 of 25 districts in Ankara and lose

the metropolitan. Does that make sense to you? There is a

trick, a trick.

A Dissident: “I would not vote if it was not for you

and the ones like you. There are thousands of people

like me. Thank you for your contribution to the

CHP.”

Former Ankara Mayor Melih Gökçek: “Think: On 31 March

evening ballot boxes are opened, CHP convoys in streets,

PKK flags and posters of APO waved in cars, screams of joy

at Kandil, victory parades from FETO. If these do not affect

“I was not going to vote. This nice tweet of yours

made CHP get one more vote.”

AKP's mayoral candidate in Ankara Mehmet Özhaseki: “If

the CHP wins, then the PKK and DHKP-C will say that "We

have given you support, it is now your turn". God forbid,

imagine that a militant is bringing utility bill to your house.

Think about the catastrophes that will happen to us.”

“I was not going to vote. But thanks to these

statements, AKP and MHP consolidate us as

opposition very well. CHP could have not been able

to do that for decades. I gave up on my former decision, I am going to vote.”

Here dissidents thank an AKP politicians and supporters because they contributed

to the CHP’s victory by manipulating people with unfounded allegations. One of

them adds that there are thousands of people like him and he is also right about

that as my research proved.

[13] Entries

On non-voting behavior:

“That was me. I was not going to vote, because I hated

opposition (not because voting is not working). Government

statements flip me out so that I decided to vote. I am going

“It was me. But I have changed my mind after the certain

person’s hate speeches, curses, insults, separatism, and now

I will go to vote.

Even a donkey would be more respectable candidate for me

than him. At least a donkey only hee-haws, there is no harm

to the nation in that.”

These entry owners seem to be in the very edge of the polarization between the ruling and opposition parties. Whoever stands against “them,” meaning AKP and

supporters, “even a donkey”, which is more respectable for the voter, will be the

ones these voters vote for “forever”. Voting is obviously an act that people use to

choose sides as if in a battlefield.

[14] Tweets

“After the Ekmeleddin fiasco, I approached Ekrem

İmamoğlu with prejudice. I did not even vote because of my

anger at Kılıçdaroğlu. But after RTE's hatred and hate

speech, I felt compelled and cast my vote.

I hope that RTE can derive necessary lessons from

this policy of polarization and discrediting others just to be winner, and Kılıçdaroğlu can practice right

While criticizing CHP’s candidate policy and indicating that this was the reason of this voter to decide not to vote, he says that the President’s language full of hatred

just to win in elections made him feel “have to vote” and he thus cast his vote.

[15] Tweets

“Actually, I was not going to vote in these elections, but my

decision changed when I saw the judges and politicians who

wanted to close the files of Şule Çet and Rabia Naz. I would

vote even for the devil just to take the power from your hands.”

“I was not going to vote. Just said “It is too hot; I cannot

bother myself with voting.” Then, Ali İsmail Korkmaz came

to my mind. I went to vote while cursing myself.”

There were statements on some social issues (such as murder cases of Şule Çet

and Rabia Naz) which were bothering people due to deteriorations in the judicial

and legal system. Dissidents went to the polls just to take powers from the hands

of politicians who cover up such cases unlawfully. “Even evil” seems to get some dissidents’ vote versus “them”.

[16] Tweets

“I did not intend to vote in this election, but the President

called everyone terrorist including people who were standing against the PKK and FETÖ. I vote for the CHP.”

“I did not think of voting until now, but I decided to vote

after this statement, “those who are not of us are terrorists.””

“I was not going to vote. My hope was over; I do not think

the votes were counted fairly. As I see what is happening, I

cannot bear seeing the people who support the person who

polarizes and divides people every day. We will not give them what they want. We will cast our vote.”

“Let me relax you a little, you are too tense. In fact, most of

us would not vote after the June 24, but when RTE turned

the elections to a referendum, we went to the ballot box due

to anger he caused. So we as stone-broke sat on the

gambling table. If we lose, we are still alive, and if we win, we will win a lot. Now dance.”

“Abominations (Zillet), traitor, terrorist or something ... What

“I was not going to vote so that the chairman of CHP

would change. However, all these hate speeches will bring me to the ballot box.”

An AKP supporter: “Chaos or Stability!”

“I was going to boycott the elections. Just because of

your attitude I will cast my vote for the National Alliance (Millet İttifakı).”

These are some other tweets showing that the President, the AKP and its

supporters convinced the dissidents to vote. Calling everyone as terrorists,

polarizing people and so forth made people vote despite they said they would not

vote anymore after previous elections. In all, in contrary to Fiorina’s (2006)

suggestion that polarization is a myth (in the case of American politics),

polarization in Turkey is real and it is what made dissidents vote in the elections.

[17] I should also mention that there are also some positively encouraging

statements, rather than creating hostility, led people vote, although dissidents did

not initially plan for. One particular statement affected dissidents were HD P leader Selahattin Demirtaş’s declaration telling people “harden their hearts and

vote” as a favor (hatırı için) for him. Many people seem to listen to him and vote

in spite of their contrary statements on voting. Here are a couple of tweets on this