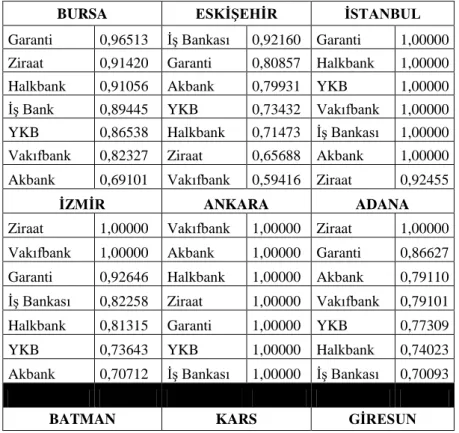

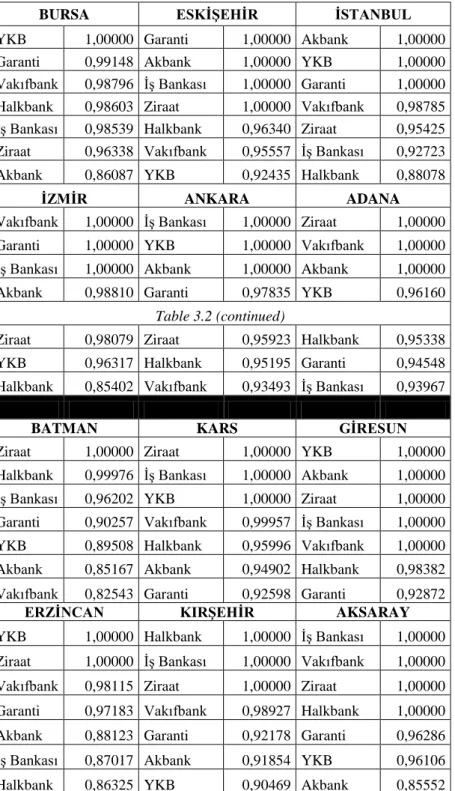

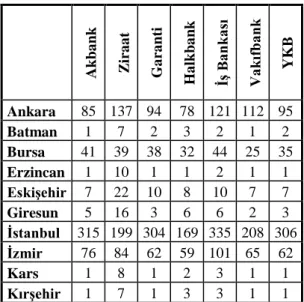

Regional efficiency analysis of Turkish commercial banks with the use of data envelopment analysis between years 2007 - 2012

Tam metin

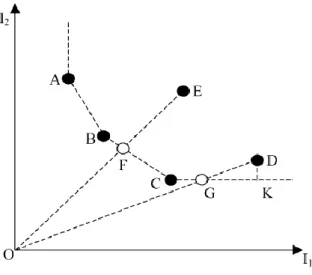

Şekil

Benzer Belgeler

Dolayısıyla insan merkezli olan Bektaşi ve Alevi kültüründe Tanrı, herkesin tanrısıdır, ibadet herkes içindir, bu nedenle kadın ve erkek beraber ibadet eder.. Onlar

O zamanlar Boğaziçi cennetten bir nümuney- di. Hele mehtab geceleri denizin yüzü seyirci kayıklarile resmi ahnacak bir şekil ve mahiyet teydi. Malûm ya, en güzel

Multicomponent Efficiency Measurement and Shared Inputs in Data Envelopment Analysis: An Application to Sales and Service Performance in Bank Branches.. Sales

Araştırmada, Google Lighthouse analiz aracının ölçtüğü SEO skoru ile arama motoru sonuç sayfalarında ortaya çıkan sıralama arasındaki ilişkinin tespit

Lomber KMY sonuçlar› gruplar kendi içinde tedavi sonras›, öncesiyle karfl›- laflt›r›ld›¤›nda istatistiksel olarak anlaml› bir iyileflme saptand› (alendronat

Resveratrolün Kardiyovasküler Hastalıklar Üzerine Etkileri Effects of Resveratrol on Cardiovascular Diseases.. Enver Çıracı 1 , Tuğçe

[r]

symptoms before or after diagnosis were more likely to adhere to self management activities than those who were uncertain; (3) the findings of confirmatory factor analysis