Foreign direct investment in Turkey: determinants, problems, tax and legal changes

Tam metin

Şekil

Benzer Belgeler

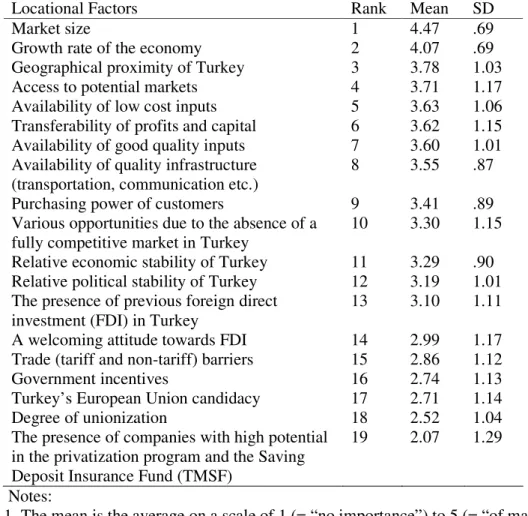

In his research, Bosut (1999) describes Turkey as a large and growing domestic market for the foreign investors. Its proximity to the emerging markets in the Middle

According to the data and chosen period, the mean for exchange rate is reported to

The foreign investments was affecting Jordan in a positive way, but recently the situation changed, and this type of investments started to affected the Jordanian economy in

Bu çalışmada, 3D yazıcılar için geliştirilen elyaf takviyeli ince agregalı yüksek performanslı betonun karışım tasarımı ile taze ve sertleşmiş hâlde beton

(‹ki boylam aras›nda zaman farkl› 4 dakikad›r. Buna göre 0 ile 15 derece boylam ara- s›nda bir saat, 0 ile 30 derece boylam aras›nda 2 saat zaman farkl› bulunur.)

Oysa, ~ngi- lizler tüm alanlarda faaliyet gösteriyorlar ve Vikers Arm-strong veya Brassert gibi büyük firmalar birinci s~n~f teknisyenlerini de içeren heyetleri

Modelde grup içi çatışma, gruplar arası çatışma ve kişilerarası çatışma değişkenlerinin örgütsel çatışmayı anlamlı bir biçimde

DSM-IV-TR'nin (American Psychiatric Association 2005) kesin taný kriterleri nedeniyle somatizasyon bozukluðu aslýnda seyrek rastlanan bir durumdur; oysa daha hafif bir formu