KADİR HAS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES

PROGRAM OF ENERGY AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

THE INTERNATIONAL POLITICS OF CLIMATE CHANGE: BARGAINING

AND NEGOTIATION PROCESSES FROM KYOTO TO PARIS

MELİKE EKEN

SUPERVISOR: PROF. DR. VOLKAN Ş. EDİGER CO-SUPERVISOR: ASSOC. PROF. H. AKIN ÜNVER

MASTER’S THESIS

Me like E ken M.S. The si s 2019

THE INTERNATIONAL POLITICS OF CLIMATE CHANGE: BARGAINING

AND NEGOTIATION PROCESSES FROM KYOTO TO PARIS

MELİKE EKEN

SUPERVISOR: PROF. DR. VOLKAN Ş. EDİGER

CO-SUPERVISOR: ASSOC. PROF. H. AKIN ÜNVER

MASTER’S THESIS

Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Kadir Has University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s/PhD in the Discipline Area of Energy and Sustainable Development under the Program of Energy and Sustainable Development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Dr. Volkan Ş. Ediger who provided me an opportunity to be a MA student at the Energy and Sustainable Development Master Program of Kadir Has University. I would also like to thank my co-supervisor, Assoc.Prof. H. Akın Ünver for his guidance and encouragement in my graduate studies. Without the precious comments, remarks and suggestions of my supervisors, this thesis would not have been successfully completed. They always support me to be my own person in my work, and encouraged me towards the right path.

My thesis was also made possible in part by scholarships from the Kadir Has University.

My sincere thanks go to my colleagues at Kadir Has University who stood by me, especially Hazal Mengi Dinçer and Şebnem Sezgin whose encouragement and kind support I very much appreciate. I am also glad to Dr. John W. Bowlus for his help for correcting grammar. I would also thank to my dear friends for showing their understanding and love in helping me complete my thesis.

I finally extend my acknowledgement to my parents and brothers, Hatice, Kadir, Mert Can and Melih Eken, who always stand behind me with their best wishes and sincere support.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ………... i-ii

LIST OF TABLES ………... . iii

LIST OF FIGURES ………...……….. iv

ABSTRACT ………. v

ÖZET ……… vi

INTRODUCTION ……….. 1

1. UNDERSTANDING CLIMATE CHANGE………... 6

1.1. Climate Change As A Scientific Fact………... 6

1.2. Policy Portrait of Climate Change by UN………... 8

1.3. Climate Change as An Economic and Political Issue………... 9

1.3.1. Energy security matters on way of climate change policies………... 9

1.3.2. Economic burden of climate change policies………. 11

1.3.3. Political and social issues behind the climate change policies…….………….. 12

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: NEOLIBERALISM & CRITICAL THEORY………... 14

2.1. Theoretical Background of Neoliberalism………... 14

2.2 Theoretical Background of Critical Theory………... 16

3. TIMELINE OF CLIMATE CHANGE NEGOTIATIONS………... 21

3.1 International Initiatives before the UNFCCC………... 21

3.2. The Adoption of the UNFCCC and UN Negotiations Timeline……… 22

3.3. The First Treaty on Climate Change: KP……… 24

3.4. The Process after KP: Bonn Agreement and Marrakesh Accords………. 25

3.5. Kyoto Protocol Enters into Force………... 27

3.6. Nairobi Work Program: Use of Knowledge ……….. 27

3.7. IPCC Fourth Report Leads to Bali Roadmap………... 28

3.8. Poznan Strategic Programme and Copenhagen Accord………. 28

3.9. Cancun Agreements………... 29

3.10. Durban Platform: Construction of PA……….. 31

3.11. Second Commitment Period of KP………... 32

3.12. Warsaw Outcomes: Securing Way of a New Agreement………. 32

3.13. Milestone for Negotiations: PA………... 33

3.14. Subsidiary COPs after the PA……….. 35

4. THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF KP AND PA ……… 40

4.1. Neoliberalism Analysis for Signing Process both of KP and PA .………... 40

4.2. Implementation Process Analysis of Both Agreements with Critical Theory………. 46

CONCLUSION………... 57

SOURCES……….. 61

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

ADP Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action

AF Adaptation Fund

AFB Adaptation Fund Board

AWG-KP Ad Hoc Working Group on Further Commitments for Annex I Parties under the KP

AWG-LCA Ad-Hoc Working Group on Long-Term Cooperative Action under the Convention

CC Climate Change

CDM Clean Development Mechanism

CERs Certified Emission Reductions

CH4 Methane

CO2 Carbon Dioxide

COP Conference of the Parties

ERU Emission Reduction Units

EU ETS EU Emission Trading System

GCF Green Climate Fund

GHG Greenhouse Gas Emissions

HFCs Hydro Fluorocarbons

INC Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee INDCs Intended Nationally Determined Contributions IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

KP Kyoto Protocol

LDCs Least Developed Countries LDCs Least Developed Countries

LRTAP Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution

MARPOL International Maritime Organization developed by International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships

MOP Meeting of Parties

MRV Measuring, Reporting, and Verification

N2O Nitrous Oxide

NAMAs Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions NDCs Nationally Determined Contributions

NWP Nairobi Work Programme

O3 Ozone

ODSs Ozone-Depleting Substances

OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

PA Paris Agreement

PAMs Policies and Measure

PFCs Perfluorocarbons

SBSTA Subsidiary Body established a program for Scientific and Technological Advice

SF6 Sulphur Hexafluoride

SIDS Small Island Developing States

UN United Nations

UNCBD UN Convention on Biological Diversity UNCCD UN Convention to Combat Desertification

UNEP UN Environment Programme

UNFCCC United Nations of the Framework Convention on Climate Change

WMO World Meteorological Organization

LIST OF TABLES

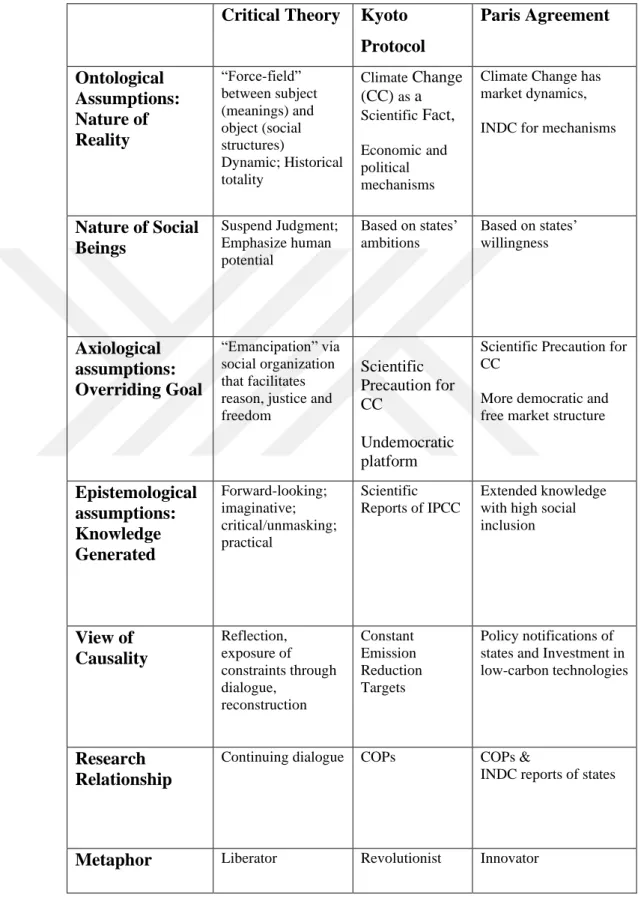

Table 3.1 Summary of COPs and their Outcomes………38-39 Table 4.1 Summary of Neoliberalism and the Accords……….………...45 Table 4.2 Summary of Critical Theory and the Accords………..55

LIST OF FIGURES

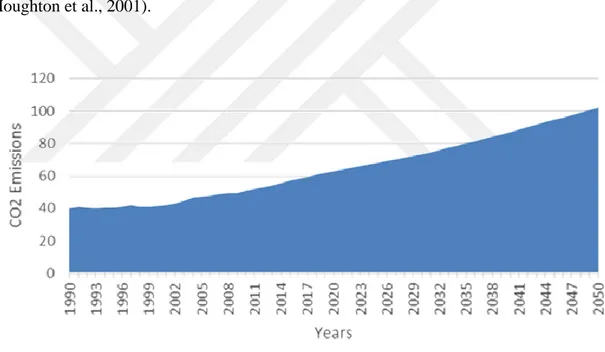

Figure 1.1 2050 Global CO2 Emissions Projection ... 1

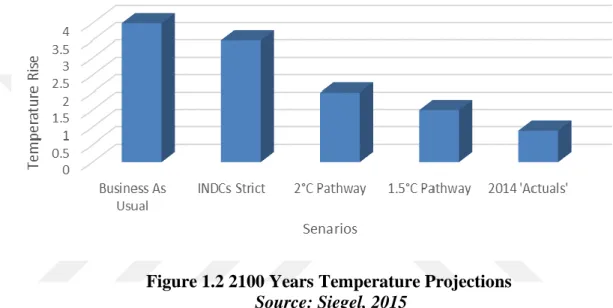

Figure 1.2 2100 Years Temperature Projections ... 7

Figure 4.1 CO2 Emissions of Top 10 Emitters in 2014 ... 43

Figure 4.2 Top 10 Emitter Countries in 1996………… ... 47

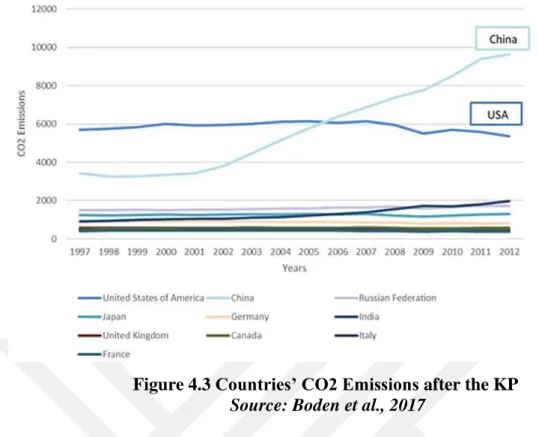

Figure 4.3 Countries’ CO2 Emissions after the KP ... 50

Figure 4.4 CO2 Emissions of Top 10 Emitters from KP to PA ... 50

Figure 4.5 GDP Growth by Top 10 Emitters ... 51

THE INTERNATIONAL POLITICS OF CLIMATE CHANGE: BARGAINING AND NEGOTIATION PROCESSES FROM KYOTO TO PARIS

ABSTRACT

Climate change is actually a natural phenomenon that occurs throughout history. In time, the climate can change do warmer or cooler in specific periods. But essentially with the industrial revolution, the human-induced activities trigger the climate change and the global temperature increase than the normal course of business. So, the fossil fuels which are used in vast scale among other energy sources cause to raise carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions to the atmosphere. The high degree of CO2 emissions are related to the greenhouse effect in the atmosphere and this effect harms ecosystems and life of both human beings and non-human beings precisely. In that point, the foundation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is an essential institution to regulate climate change governance. It establishes several negotiations and two binding treaties: the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement. In order to understand signing success of both agreements and their problematic implementation process, it will be used two theories of international relations discipline (IR): neoliberalism and critical theory. Complex-interdependence matters in neoliberalism to understand the actors’ policies for signing these accords. On the other hand, the emancipation issue of critical theory will explain the commitment issue of the Parties in the implementation process of accords. It will be expected that this study reveals that the multilateral relationship of the states refers to complex-interdependence, and it triggers to sign the accords. Also, it will be aimed to understand that the problematic side of accords is related to the emancipation of climate change as only an environmental issue from economic and political interests. In order to observe the evolution, the timeline of the Conference of Parties (COPs) in the process will be put in place with the IR concept of audience cost.

Keywords: Climate Change, Kyoto Protocol, Paris Climate Agreement, Critical Theory, Neoliberalism, Commitment, International Cooperation

ULUSLARARASI İKLİM DEĞİŞİKLİĞİ SİYASETİ: KYOTO'DAN PARİS'E PAZARLAMA VE MÜZAKERE SÜRECİ

ÖZET

İklim değişikliği tarih boyunca meydana gelen doğal bir olgudur. İklim belirli dönemlerde daha sıcak veya daha soğuk hale gelebilir. Ancak, esasen sanayi devrimi ile birlikte insan kaynaklı faaliyetler iklim değişikliğini ve küresel sıcaklık artışını normal iş akışına göre tetiklemektedir. Endüstriyel faaliyet arttıkça enerji üretimi ve tüketimi de artmaktadır. Bu nedenle, diğer enerji kaynaklarına göre daha fazla kullanılan fosil yakıtlar atmosfere karbondioksit (CO2) salımlarının yükselmesine neden olmaktadır. Yüksek CO2 salımları atmosferdeki sera etkisi oluşturmaktadır. Bu etki ekosistemlerle birlikte hem insan hem de diğer canlıları etkilemektedir. Birleşmiş Milletler İklim Değişikliği Çerçeve Sözleşmesi (UNFCCC), her yıl gerçekleşen iklim değişikliği müzakereleri ve iki bağlayıcı anlaşması: Kyoto Protokolü ve Paris Anlaşması ile iklim değişikliği yönetişimini yürütmektedir. İklim değişikliği politikalarının oluşum ve yönetim sürecini anlamak için iki uluslararası ilişkiler disiplini teorisi kullanılacaktır. Anlaşmaların imzalanmasının başarısını neoliberalizm’in karşılıklı bağımlılık ilkesi ile açıklanırken, ilgili anlaşmaların uygulama sürecinde tarafların taahhütlerini eleştirel teori’nin özgürleşme konusu özelinde tartışılacaktır. Bu çalışmanın, devletlerin çok taraflı ilişkisinin karşılıklı bağımlılık ilkesi etkisi altında oluştuğu ve anlaşmaları imzalamayı tetiklediğini göstermesi beklenmektedir. Ayrıca, anlaşmaların uygulama sürecinde karşılaşılan sorunların, eleştirel teori bazında ele alınıp iklim değişikliğinin ekonomik ve politik çıkarlardan evrensel bir çevre sorunu olarak ayrışamaması incelenecektir. İki anlaşma arasında gerçekleşen evrimi gözlemlemek için, süreçte yer alan Taraflar Konferansı’nın çizelgesi izleyici maliyeti kavramında tartışılacaktır.

Anahtar Sözcükler: İklim Değişikliği, Kyoto Protokolü, Paris İklim Anlaşması, Eleştirel Teori, Neoliberalizm, Tahahhüt, Uluslararası İşbirliği

1

INTRODUCTION

As the demand for energy has grown across the globe, there has been a commensurate rise in the release of carbon emissions into the atmosphere (Iwata et al., 2012). This is due to the way that energy, namely fossil fuels, on which global energy consumptions rests, are produced. The combustion of fossil fuels for energy is the primary reason for today’s rising levels of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG). As figure 1 presented, global carbon emissions over the years and as projected to 2050 according to baseline scenarios1. These emissions have, in turn, led a new and challenging problem: global climate change (Karl et al., 2009). Global climate change, defined by the United Nations (UN) as catastrophic long-term change in climate, has broad adverse effects for the environment (Balbus et al, 2013; Houghton et al., 2001).

Figure 1.1 2050 Global CO2 Emissions Projection, 1990-2050 Source: Siegel, 2015

Change has created a global environmental problem that threatens to future of humanity. This period creates a new phenomenon in which the damage to whole ecosystem from human-induced activities is more influential in warming the planet than natural volatility in climate patterns (Boden et al., 2010; Solomon et al., 2007; Stocker et al., 2013). This new international environmental crisis triggers to new set of questions about survival, self-help

1 “Baseline Senarios” which mentioned by the IPCC AR5 Working Group in Kyoto are estimated based on CO

2

2

and national interests, as conceptualized by international relations and has emerged during the anthropocentric period (Steffen et al., 2007). There are several reasons, both natural phenomena to human-induced activities, especially those after the Industrial Revolution that are disturbing the normal pace and rhythm of climate change and warming the planet (Houghton, 1994; Weaver et al., 2013). Climate change also creates vulnerability for people and living creatures and deteriorates our collective ecosystems. So, it is significant to take steps for improving climate change policies and reduce the future vulnerability of life on the planet. The term of vulnerability is referred as the state vulnerability which means that what extend the states are imposed negative effects of the climate change (Harris and Roach, 2013; Yamin and Depledge, 2004). Climate change also has an interrelated relationship with the global economic and political issues of the states (Frankhauser and Tol, 2005; Thorpe and Figge, 2018). The main reason is that this problem extends beyond natural border within the context of a cause and effect relationship (Dalby, 2003; Keohane and Victor, 2016). However, it is difficult for states to establish a common solution for this global problem because every country is influenced by climate change in different scale and in different ways across different regions (Balbus et al, 2013). So, the states are inclined to consider their interests on growth, competitiveness, security and public finance at the same time as climate (Sassen, 2000). As such, each actor has own economic and ideological priorities in the policy-making process of climate change (Leiserowitz, 2006).

The solution, however, may be dealt with both individually and by the collective action of states. According to Wood and Vedlitz (2007), global climate change policies should be conducted in global level. All states need to understand that climate change is a common problem of humanity (Chan, 2018). They search for a universal solution to establish a common policy (Busby, 2003). This solution should also create a win-win solution for all to increase their abilities. At the global level, there have been several international negotiations and some global agreements signed over time. Initially, there were initiatives on different, specific issues related to climate and environment. The earliest initiatives, for example, were the following: the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling in 1946 to protect oceans’ ecosystem, the Geneva Convention on Long-Range Trans boundary Air Pollution in 1979, and then Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer in 1987.

Essentially, the World Climate Conference in 1979 by the World Meteorological Organization was the first substantial attempt to shape climate change governance. Then,

3

the foundation of United Nations of the Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992 was a foundational step. The UNFCCC has since had a most prominent role in supporting the global response to the threat of climate change (Ediger, 2017; Vandeveer, 2002). There have been several negotiations and agreements established under the UN secretariat. Among these, the Kyoto Protocol (KP) (1997) and Paris Agreement (2015) have made an overwhelming impression in the international area. The KP triggered a new beginning of efforts and partnerships to formulate climate change policy and led all major carbon emitters to enter into negotiation (Streck et al., 2016). During subsequent years, several bargaining and negotiation processes had been taken place. Finally, the Paris Agreement (PA) was adopted in 2015 (Rajamani, 2016).In these international negotiations, there was collaboration to create efficient solutions for emission reduction, the utilization of natural resources, corruption of ecosystem, drought and waste management (Ilcan, 2006). The primary purpose of the study is to understand that the signing moment of both the KP and PA is a success for climate governance, while their implementation processes are problematic for the commitments of the Parties. For this purpose, two theories of the international relations discipline will be applied: neoliberalism and critical theory. In order to analyze the make-up process of successful accords, the concept of complex-interdependence of neoliberalism will be used. Then, the policy implementation process dynamics will be explained by the concept of emancipation of critical theory. This process has produced both positive and negative parameters for the commitments (Wigley, 2005). So, the process between both agreements will be examined with International Relations concept called 'audience cost.' The process from the Kyoto until the PA which provides transition of states' approaches towards commitments via several sufficient funds, activities, and programs of UN will be put with the concept of "audience cost" for states (Lohmann, 2003; Tomz, 2007). The Conference of Parties (COPs) which are assigned by the UNFCCC annually are explained in detail in a timeline to understand how they put "audience cost" for state's leaders.

In the methodology of the study, analyzing the existing literature on the issue uses the qualitative analysis. Indeed, the process tracing method which is a tool of qualitative analysis is applied (Collier, 2011). This method includes that a review of specific issue is made with a cumulative examination of different activities or acts of a particular character which have relatedly causal link to the point in a specific period (Beach, 2017; Collier, 2011, Crasnow, 2001). In quantitive explanatory research, analyzing climate change

4

negotiations fall apart in two manners in general. Some researcher focus on a divided part of parties rather than an evaluation of the whole community (Genovese, 2014). This way maybe helps to evaluate the theoretical framework of the decisions (Hovi and Areklett, 2004), but it lacks to explain their practice (Barret, 1999). Some are dealing with the set of issues of the negotiations (Grundig, 2006; Ward et al. 2001), but in here, the researchers fail to notice that there is a lack of information about the bargained issues (Genovese, 2014). The analyses are based on long-term emission reduction targets (Jensen and Spoon, 2011), and previously-defined responsibilities of the parties (Lange et al. 2007). In qualitative explanatory research, in approach of the rationalist institutionalism, states' binding attitude to the cooperation change according to their interests on benefits and cost related to the cooperation (Abbott and Snidal, 2000). Their interest mostly related with their vulnerability level to climate change (Bailer and Weiler, 2015; Dolšak, 2009; Sprinz and Vaahtoranta, 1994). Especially for the countries which their energy production derived from fossil fuels have a vast amount of cost to transform their economic structure for new emission-mitigate technologies (Aldy et al., 2003; IPCC, 2011, Chapter.9). In neorealism, the states which have a strong power presence in international world politics affect to the legalization of commitment roadmap (Baumann et al., 1998; Brooks 1997).

In that point, the UN negotiation and bargaining activities are supplied as causal mechanisms for commitment to two agreements defined as a specific outcome or actual case. The decisions of COPs are analyzed for settlement of “audience cost” and new international economic order for establishing a platform to the high level of participation about the commitment (Chaudoin, 2014; Eyerman and Hart, 1996; Lohmann, 2003). In order to evaluate the whole negotiation process, the official websites of the UNFCCC, World Bank and OECD are appealed to take real-time data processing about the negotiations. The comparative analysis of two agreements is reviewed respectively. Conceptual framework of critical theory and neoliberalism evaluates pre-conditions and afterwards.

This study is composed of three chapters. In the first chapter, climate change is defined and discussed as a scientific fact by the literature and UN assessment reports. In addition to environmental background of the issue, the scope of the climate change also complies with the political and economic parameters of world politics. There are several dynamics that are fundamental to understand in terms of how climate change can be understood in international politics.

5

In the second chapter, a detailed theoretical analysis is provided. Initially, neoliberalism will be applied to understanding the dynamics towards adopting the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Climate Agreement. The concept of complex interdependence reflects implications to explain the pathways towards both agreements. Then, critical theory helps with the concept of emancipation, which helps to reveal why their implementation process continues problematic for governance.

In the third chapter, the timeline of international negotiations is examined to understand better how the issue of climate change has evolved in the international arena. The information about negotiation processes comes mainly from the UN official website. In the beginning, it is proposed that the timeline of the talks starts from some different initiatives before the establishment of the UNFCCC in 1992, and it continues with the UNFCCC negotiations, and ongoing negotiations until today. Within these negotiations and bargaining processes, two critical binding treaties – Kyoto and Paris – will receive the most focus. The timeline between two agreements is essential to evaluate because the aim, scope, and direction of the negotiations reflect how climate change policies have been shaped and have evolved.

This study uses the Kyoto-Paris timeline to understand the dynamics of the negotiation processes in climate change governance through a theoretical structure. It is anticipated that these theories will enable readers to understand more clearly the functions of international mechanisms for addressing climate change.

6

CHAPTER 1

UNDERSTANDING CLIMATE CHANGE

In this chapter, the central issue of international negotiations over climate change is observed through the scientific, economic and political scope in detail. Firstly, there are some experimental pieces of evidence and then the UN’s studies to conceptualize climate change. Also, the political and economic dimension of climate change is discussed with the existing literature.

1.1. Climate Change as A Scientific Fact

Climate change is defined as a periodical change in temperature in the climate that occurs throughout the history (Justus and Fletcher, 2006). This change may be an increase or decrease in the temperature and leads to severe adverse effects that shape the atmosphere and ecosystems (Gore, 2006). GHGs are the most significant component of global carbon dioxide emissions, which have resulted from the use of carbon-based energy sources including coal, oil, and gas. Greenhouse gas emissions consist of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydro fluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), and Sulphur hexafluoride (SF6). Some GHGs comprise water vapor and ozone (O3), others come naturally (Grossman, 2010). The existence of these gases provides a balance of temperature to the atmosphere. But an excessive increase in their output creates a greenhouse effect that prevents the filtration of infrared radiation in the atmosphere (Dutt and Gaioli, 2007). Greenhouse gases absorb existing radiation within the atmosphere, and this imbalance of radiation triggers temperature to increase. Although oxygen and nitrogen are "transparent to terrestrial radiation," other GHGs are inclined to absorb terrestrial radiation that abandons the Earth's surface. Rising concentrations of GHGs cause "positive radiative forcing," which causes an increase in the absorption of energy on the planet. This situation results in the increase in the Earth's temperature, referred to as global warming (Grossman, 2010). Leading the agriculture, sea level, forests and water resources are adversely affected by the temperature rise (Ediger,

7

2008; Titus, 1992).It is a scientifically proven fact that temperature is rising. Figure 1.2 indicated that if business as usual activities continues, the temperature increase about to 4°C (Cubasch and Bruns, 2000). In other conditions which are derived from PA’s Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) and aims of 2°C with 1.5°C limit to emissions, the temperature increase about 2°C to 2100 years. This, in turn is triggering the international community to seek way to limit the increase to no more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels (Falkner, 2016; Sims, 2004; Tol, 2007).

Figure 1.2 2100 Years Temperature Projections Source: Siegel, 2015

The climate is calmer than the past over the last decades, and this change has already caused great harm to the environment and will continue do so in the future.

It is a well-known fact that climate change does not affect countries to the same degree (Dupond and Pearman, 2006). Every state is exposed to different degrees of climate change. A wide range of climate change effects occurs in different regions. In the southern hemisphere, warmer temperatures lead to drought in agricultural lands and deforestation as well as water flooding incidents (Detraz and Betstill, 2009). On the contrary, in the northern hemisphere, new ice-free sea-lanes are emerging in the Arctic, which enables countries to extract more resources there. For instance, low-lying, island states may confront an extreme level of threat from the rise of sea levels, while countries closer to the equator may experience desertification because of extremely high temperatures. Northern countries see climate change as a chance for their land accretion. These unequal outcomes create a deadlocked situation for international climate policies (Detraz, 2011; Falkner, 2016). They obfuscate future predictions and

8

create uncertainty for about the long-term costs for states. But GHGs’ adverse effects spread globally and accumulate. They will be with us for long periods of time.

1.2. Policy Portrait of Climate Change by UN

The United Nations firstly contextualizes climate change with the foundation of the UNFCCC. The UNFCCC defines climate change as “a change of climate that is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere, and that is in addition to natural climate variability over comparable periods” (UNFCCC, 1992). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) centers upon more scientific side of the climate change by that definition as "any change in climate over time whether due to natural variability or as a result of human activity" (IPCC, 2007). These definitions aim to support each other, but they create a different implication for defining climate change. Both politically and scientifically, the descriptions are not compatible. This situation causes a lack of coherence in policymaking. The lack of coherence creates a stalemate on international climate policies. This stalemate is a critical issue that needs to be solved. Applying effective policy actions cannot wait because climate change is a real fact.

There are several working groups in the UN for climate change politics. Its working group on science prefers the IPCC definition, and the other working group on economics appeals to the UNFCCC’s definition, while another working group on vulnerability, impacts, and adaptation applies both definitions (Pielke, 2004). It can be achieved by mitigating the elements that trigger climate change and be framed by adapting to the features that make environment and society vulnerable to these changes. The policies of the UN have been divided in two ways: mitigation policies and adaptation policies. Mitigation policies attempt to control and constrain the scale of greenhouse gas emissions. Adaptation policies deal with making social and environmental systems more tolerant to climate change effects. Nevertheless, climate policies have been reluctant to embark on adaptation side, widely because of confounding definitions of climate change (Pielke, 2004). The establishment of an effective policy needs to merge and combine both mitigation and adaptation policies. The different interpretations limit the adoption of wholesale climate resilience policies.

9

Having a bias towards adaptation is echoed in the different attitudes of the IPCC towards climate change.

Also, Torvanger (1998) points out that adaptation cost is one of the greatest challenges for climate change policies. It cannot be measured in a fixed way because of changes in society and ecosystems over time. There are different adaptation measures for a wide range of future possibilities that can be unleashed climate change. According to him, adaptation policies are needed to make investments for the long term. For example, building infrastructure that helps to reduce climate change vulnerability is essential for adaptability. These kind of investments do not affect global warming implications, but at least they may reduce the costs of social and natural damage from climate change. As a result of this attitude, in policy discussions, there are some political tensions about mitigation and adaptation policies. Although mitigation-based policies become apparent, both policies should be based on adaptation in order to establish successful climate change policies. Falkner (2016) states that the uncertainty about the conclusions of climate change for countries creates ambiguity for putting together particular policies. They have difficulty to put an efficient provision of a global ‘public good' in this issue because states consider their national interests first before the global issue of climate change.

1.3. Climate Change as An Economic and Political Issue

In international politics, it is challenging to establish a common cause for any issue. Achieving a global political consensus is quite difficult. Kingdon (1995) contends that the policy agendas of world politics are always divergent and crowded, while the political capital is insufficient to deal with that. Climate change, as an international political issue today, is associated with energy security, economic development, and the social and political crises of the states fundamentally.

1.3.1. Energy security matters on way of climate change policies

In energy politics, there are different parameters for influencing political actors. Geographical features, security matters, economic developments and also environmental concerns are essential parameters for energy politics. Every state has

10

different geographical features, so each country is influenced on a different scale from any geographical facts in the world. The geographical features may gain the countries have a wealthier or poorer identity and enable some advantages or disadvantages among others. Some countries have more resources or have a better strategic location; meanwhile, other countries may not possess one of them or both. There is an inequality of geographical features among countries, in other words, which creates a geographical ground for conflict between states' interests and leads to the use of energy resources as soft power in international relations.

Geopolitics, as a concept, are "a study of the influence of geographical factors on political action" (Winrow, 2007). Hence, current interpretations of geopolitics imply that geopolitics has gained a more diversified and concrete meaning and also a wider range of dynamics in international relations. When talking about the economic side of geopolitics, it is necessary to correlate with the location of energy sources. According to Winrow (2007), geopolitical factors must be considered in light of the location of energy sources in order to understand states’ foreign policies in the energy market. The crucial reason is that energy sources are unequally distributed geographically, which makes it an important factor in geopolitics. Also, energy sources are critical to the economic and political goals of states and are thus critical to secure.

In addition, energy security means the procurement of energy from the producer in a secure, uninterrupted, efficient and cheap manner (Pamir, 2007). Energy should be always supplied in that manner and protected from "political intervention; sanctions; invasion; terrorist attacks, sabotage; technical failures; under-investment (exploration, production, refining, etc.); economic problems (inability to pay); poorly designed markets; accidents; and storms like hurricanes” (Pamir, 2007). All these factors prevent energy from being supplied properly and contribute to energy insecurity, which shapes energy politics and international relations. So, geopolitics and energy security both have shaped world politics. Hence a new conception of energy geopolitics, a combination of energy-security politics and geopolitics, has taken hold in the literature (Westphal, 2014).

In this context, climate change falls within the parameters of geopolitics and energy security. The international climate change policies shaped in terms of security matters of states as well. According to Ünver (2017), the prerequisite of successful climate

11

change negotiations is the establishment of a mechanism that provides energy security matters for states. In parallel with energy security matters, there are both supporters and opponents about that climate change a security issue2 (Baysal and Karakaş, 2017). These supporters can be divided into two categories: the ones who mention ‘human security implications’ like food insecurity (Brown and Crawford, 2009), and the others who discuss ‘traditional security implications’ such as violent conflict and climate migration (Baysal and Karakaş, 2017: 40; Gleditsch, 2012).

1.3.2. Economic burden of climate change policies

Climate change policies also have an economic dimension in world politics. In the modern world, economic development is largely based on the efficient use of energy in industry. This dynamic prompts people to use fossil fuels, which in turn leads to a high level of carbon emissions being released into the atmosphere. Since carbon emissions are the leading cause of global warming, it is the industrial system that must be altered or changed.

To this end, de-carbonization needs to take a new priority as a new economic model in the global economy. De-carbonization aims to have more clean energy sources and technologies that release fewer carbon emissions. In this light, renewable energy technologies can play a critical role in expanding the low-carbon economy. With innovation in energy technologies and their production methods also bring about energy efficiency. New technologies promise a cheaper and more sustainable way to transition into de-carbonization (Cline, 1992; Nordhaus, 1991).

On the roadmap to a low-carbon economy, carbon storage and capture technologies can help reduce carbon dioxide emissions on a large scale. But these technologies are still in the early stages of development and have yet to be implemented on a commercial scale. Others, including high-capacity Nano batteries and synthetic algae can be developed after large-scale investment (Falkner, 2016). For instance, the EU adopts Lisbon Strategy which aims to transform the current economy to a more sustainable version combined with sophisticated technology and social inclusion (World Economic Forum, 2008). In this strategy, the EU planned to reduce emissions with a transition to a low-carbon economy with energy efficiency priority until 2020. Mostly the low-low-carbon

12

energy transition strategy includes the usage of renewable energy technologies (Tilford and Whyte, 2010). The EU does not actualize its target entirely because of the 2008 global economic crisis, but it continues to apply low-carbon energy transition strategies today (Atik, 2017).

To established a well-structured climate change policy, it is also necessary to regulate economies but the burden of such regulations are costly to states’ economies (Sullivan, 2009). Subconsciously, this triggers states to behave timidly and adhere to their own short-term agendas that seek to reduce cost. The fact remains that states' political desires or interests in energy sources contravene their financial interests in the energy market (Tonnesson, 2007).

Climate change policies can be managed effectively if all government authorities institute significant alignments with low-carbon transition methods in their private portfolios. Many countries are applying important and necessary state-based climate change policies, such as having regulations and laws that seek to reduce energy-intensity through market-based instruments (Falkner, 2016). There is a tendency of states to support innovations in low-carbon, sustainable technologies (Nyquist, 2015). To establish an effective and beneficial international policy for all, they primarily try to develop a shared sense of the problem, regardless of their investments. Even though there is well-grounded scientific evidence of the climate change, good policy-making is still elusive. Because of the rationality in the policymaking process, states are inclined to take a "wait-see approach" to implementing such emissions-reducing policies (Falkner, 2016).

1.3.3. Political and social issues behind the climate change policies

Global climate change causes a general impoverishment in the world, but the degree of its effectiveness varies from region to region. There is a disparity about environmental conditions between North and South, poor and rich, and developed and underdeveloped countries, which raises the potential for economic crises and political tensions for all (Dupond and Pearman, 2006).

It is already clear that the decline or degradation of the environment is prompting people to migrate (Detraz, 2011). Environmental refugees cross borders to flee the

13

negative effects of climate change and are destabilizing the international world order in the process (Campbell et al, 2007). The flow of environmental refugees is straining the resources and politics of many states. At its core, it is disrupting the social and economic unity of nations by introducing irregular integration. In addition, migration creates concrete problems that countries have to address, such as supplying water and many other human needs (Brown et. al., 2007). Developing countries are especially prone to experience these problems because of their insufficient resource management (Garcia, 2010). This situation amplifies the urban-rural divide and exacerbates the global gap between rich and poor.

Environmental change also triggers conflicts such as war, terrorism, diplomatic crisis and trading disputes between states (Busby, 2007; Dalby, 2003; Homer-Dixon, 1991). These conflicts originate from the deterioration of the balance of power in economy and politics. The balance of power is inclined to collapse because global environmental damage creates instabilities regionally and globally. If the environmental problem makes these problems increasingly critical, especially in supplying food, it is easy to see how food will become a weapon. This fact is already evident today, and is stimulating adverse effects for humanity.

The potential crises driven by these instabilities can be economic, social and political. Whatever the crises, the states must develop policies along bilateral, multilateral and international lines. Although policymakers need to focus on specific commitments to solve a given problem, in reality they are inclined to shift focus from that particular issue to deal with other relevant policies at the same time. This fact produces divergent policy agendas that are not embraced in a well-structured and specific political venue. Policymakers can deal with policy agendas if they have a clear state of emergency. At that point, the state of emergency changes policymakers' political interests and forces them to act. But greenhouse gas emissions have increased so rapidly and are continue to expand the scope of dangerous to the environment precisely because national policies are so ineffective at achieving a global solution. They must, in other words, be supported by international policies.

14

CHAPTER 2

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK:

NEOLIBERALISM & CRITICAL THEORY

This chapter will explain the theoretical background of neoliberalism and critical theory. In neoliberalism, the complex-interdependence issue is essential to understand the reason for signing the Kyoto Protocol and Paris Agreement. Then for these two agreements' implementation process analysis, Critical theory helps to explain dynamics with its concept called as emancipation.

2.1. Theoretical Background of Neoliberalism

In the 1930s, the Great Depression decimated the world economy, and Keynesian theory was acknowledged as the way to combat economic recession. Keynesian theory asserted the primary role of the state to intervene to control its market economy. According to this theory, state intervention in the market provided a balanced economy by controlled fluctuations. Until the 1970s, as Venugopal (2015) stated, neoliberalism was associated with the economic ideas put forth by Friedrich Hayek and the counter-Keynesian economists of the Chicago School. By the early 1980s, there emerged a different way to define neoliberalism by arguing privatization, deregulation, and welfare-state model. This broadened economic ideas thinking to include political, social, ideological and cultural policy elements. Since then, neoliberalism has become a term used for many social science disciplines, rather than economic debates, and has shown a tendency to deal with issues of power and ideology. Clarke (2008) and Venugopal (2015) point out that neoliberalism invokes many different adjectives in a conceptual arena such as from states, spaces, and logic to privatization, regulatory frameworks, and good governance.

According to theory, the lack of a hegemonic state power in an anarchic world system creates a vulnerable legal platform for binding international agreements in policy action

15

(Keohane and Nye, 1977). Anarchic world system with free trade dynamics triggers the states to change their security understanding into a different structure. Notably, the end of the cold war enables to observe that the state can get off from security dilemma (Lebow, 2009). Neoliberalism emphasizes the existence of civil society which means that the community of people govern themselves self-rule (Peters, 2001).

Neoliberalism consists of the political and economic practices associated with free market forces and private property rights (Kotz, 2002). Individual freedom in entrepreneurship and free market economies characterize these practices and include free trade (Harvey, 2005; Parr, 2015). Neoliberalism has its own ethics system that guides all actions, especially in the economy. For instance, contractual relations in the market place are an essential ethical belief for the social good (Harvey, 2005; Treanor, 2005). The liberal market structure therefore improves human well-being in society. People with private property rights, entrepreneurial freedoms, and the free market can do more functioning economic activities (Wilson, 2018).

Moravcsik (1997) indicates Liberal theory in the context of state-society relations by saying that the societal contexts on national and transnational stage have influenced the state's behaviors in politics. According to him, societal tendency, ideas, and preferences shape strategies of the states in world politics. However, Harvey (2005) and Piven (2007) state that neoliberalism has a hegemonic power in discourse because of its having a convincing impact on different thoughts in society. These thoughts accumulate into a form of common knowledge or common sense that enables states to act collectively.

The liberal economic structure can be developed by establishing an appropriate institutional framework (Harvey, 2005). According to neoliberal institutionalist perspective, the institutions have an impact on world politics when two conditions exist. Firstly, the states have an interest in cooperation for potential gain and secondly, the institution has approach relevant to the state behavior (Keohane, 1989). Changing world dynamics to a more liberal market economy, the states tend to embark upon their own economic and politically interdependent initiatives worldwide. This situation allows states to establish policies beyond the national level and leads to corporate between them (Kotz, 2002). Neoliberalism re-conceptualizes states' power relations as

16

'responsibilization of self' under the hypothesis of governance of welfare. This responsibilization affects to the market structure (Peters, 2001).

In addition to that, the institution affects the states' policy contexts. Building an institutional framework is therefore provided by states. Neoliberalism assigns the state in this role and charges it with providing legality and security bilateral or multilateral structure and services, and guaranteeing property rights and a secure market structure (Harvey, 2005). Well-known international institutions like the World Bank, the World Trade Organization and the UN have a hegemonic power to influence the global economy and world politics (Kotz, 2002).

At the same time, political consensus in international politics is hard for states to achieve. There are divergent national interests that conflict with each other, but in some cases, states are dependent on other states for their policy actions. Usually, bilateral and international relations are dependent upon the economic, political and social connections among states. Keohane and Nye (1977) explain this with the concept of "complex interdependence", which means that modern states have different networks in the international and supranational system that diverge from national security and military issues. In field of politics, economy, communication in modern world, these networks derive from the goods, people, and money transactions beyond the national boundaries. All transactions create a new of relations beyond the military power relations for competition among the states in world politics (Keohane and Nye, 1977). Many different conceptual frameworks have become identified with neoliberalism. In the course of doctrine, neoliberalism exists as a regular phenomenon in divergent contexts, which leads to many criticisms of neoliberalism at the same time. Saad Filho and Johnston (2004) define neoliberalism as “a hegemonic system of enhanced exploitation of the majority”. It is claimed that neoliberalism contains a neo-colonial discourse that strengthens a minority power in the global system and that free market structure causes the "plundering of nations and despoilment of the environment" (Filho and Johnston, 2004). This frame has not been a well-grounded argument since the scope of neoliberalism addresses the full range of power relations not only for the interests of the minority.

17

Critical theory, also known as "Frankfurt School,” cumulates and applies social, political and cultural theories in social sciences. The Frankfurt School posits a new way of understanding Marxist revolution. It mostly criticizes Marxist parameters, which rely too heavily on economic interpretations.

Habermas (1971) argues that Marxist ideas should be considered in social and cultural upper structure of society instead of only at the sub-structural level. He focuses on the emancipation issue in the capitalist social-economic structure. The proletariat lost its potential of freedom because by transforming their understanding of emancipation in modern times. So, the concept of emancipation must be reinserted into the discussion about the capitalist system. Four transitional phases of the emancipation process occur: “from domination to exploitation; from exploitation to alienation; from alienation to liberation; and from liberation to emancipation” (Broniak 1988). Specifically, the emancipation of the individual in society is interpreted as a relationship between the proletariat and bourgeoisie. Because the working class is absorbed into the capitalist system, and in this uni-dimensional society, the majority (working class) is incapable of conceiving of an alternative system, including one that might favor them.

Specific historical and social conditions occurred at the founding of the Frankfurt School, which triggered thinking about human oppression in society, and critical theory oriented scholars toward human emancipation and liberation by applying both normative, empirical and practical discourses to observations about the social world. According to Fay (1987), critical theory enabled us to have an understanding of the oppressive features of a society. This understanding provides the basis from which to transform society and liberate humans rationally.

According to Habermas (1971), as in the capitalist system, there is a correlated relationship between knowledge and authority in conventional theories. In conventional theories, such as realism and liberalism, authority is retained by knowledge. The power of the authority is derived from the existing knowledge, and the structure is framed with that order. So, any changes are hard to establish and apply into the structure because of the hegemony of knowledge. According to Geuss (1981), critical theory claims to eliminate the conventional theories about achieving emancipation. The emancipation of

18

individual from society can only be actualized by a structure building with a critical sense.

According to critical theory, all knowledge is converted into the ideological structure because it reflects values, ideas, and the interest of social groups (Shelby, 2003). It criticizes the nature of the rational mind, positivism, the relationships between human and nature, and its progress in history. Human nature is not fixed; it was shaped by historical changes and social conditions. The theory also questions the nature of the present condition, who is served by theories, how this system can change, and how a new system could create a new intellectual framework. This intellectual framework has to change and transform according to socio-economics and political system, and must be oriented towards establishing the prospect of human emancipation (Weber, 2005). In addition to the Frankfurt School, critical theory is connected to some post-structuralist scholars, such as Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, and others. Both the Frankfurt School and poststructuralist scholars establish their theoretical positions based on Enlightenment developments. The Enlightenment foundations were mostly related to the application of human reason to political, social and cultural practices and to imaging how human potentiality can flourish in everyday life (Macdonald, 2014). The connection between human reasoning and freedom can only guide toward emancipation beyond those practices. The Enlightenment provides a philosophical ethos which is "the permanent critique of our historical era" and "the art of voluntary insubordination, that of reflected intractability” (Foucault, 2003). This philosophical ethos reflects features of the actual political and theoretical positions in the discourse of the critique.

According to Marcuse (1972), critical theory focuses on the valuation of existing political forces. In addition, Marcuse analyzes how new social and political forces can enable human emancipation. However, Horkheimer and Adorno (1972) are unwilling to accept that the Enlightenment created an "Age of Reason" that triggered significant scientific and technological developments. These developments could have helped human reasoning to dominate nature and reveal the power of instrumental rationality in social and cultural life. But in that sense, they critique reason and rationality as essentially features of domination, rather than forces that produce liberation.

19

As a scholar in the second generation of the school, Habermas (1971) reevaluated the initial claims of critical theory, especially those that thought about human emancipation as it related to the evolutionary and development processes of human society. In contrast to initial historical-hermeneutic claims, Habermas (1971) proposes a new transformation towards emancipation through the structure of language. According to him, "communicative action" can orient with socially constructed manners of unanimity and understanding enclosed within speech (Habermas, 1971).

There is a growing consensus of the failures in the Enlightenment foundations as they relate to political and ideal assembles in social life. So, earlier notions and engagement of initial critical evaluations were unable to integrate new analyses of emancipation and liberation. Hence, apart from insisting on emancipation through human rights, individual liberties, and economic equality, scholars tend to emphasize that a new mode of critique is needed to take potent political discourses into consideration (Macdonald, 2014). Also, Felix et al. (1983) put a manifestation of this notion of critique. According to them, the critical issue was to recognize that some political discourses and practices prevent the establishment of new modes of desire and becoming. Also, they argued that a common ground is needed for the possibility of emancipation, which can come about through a new linguistic play or philosophical concept.

The other important theorist is Robert Cox, the founder of Gramsci School. Cox (1983) evaluated Antonio Gramsci’s idea ‘hegemony' and added his own perspective. Gramsci defined hegemony is the process that generates "the 'spontaneous' consent given by the great mass of the population to the general direction imposed on social life by the dominant fundamental group" (Gramsci, 1971). In contrast to Marx's ideas on hegemony, in which economic parameters create oppression in society, Cox agrees with Gramsci that hegemony is a mix of consent and oppression. According to Zanetti and Carr (1997), Gramsci combines the activated, diplomatic and deliberate extents of hegemony. Engagement of different actors from international regimes on different economic activities (Cox, 1987; Murphy, 1998) to collide in the developed-states (Saason, 2000) can get along with Gramscian mechanisms of negotiation (Egan and Levy, 2003). According to Egan and Levy (2003), the Gramscian political theory defines centrality of organization and strategy; it focuses on power with its pillars such

20

as ideology, structure, and economy. The power leads to social change derives from the processing of coalition building, accommodation, and conflict.

Like aforementioned other scholars, Cox differentiated theories into two categories: problem-solving theory and critical theory. According to him, conventional theories such as realism and liberalism are the problem- solving theories, which are defined as ‘form of identifiable ideologies pointing to their conservative consequences, not to their usefulness as guides to action' (Cox, 1983). These theories guide tactical actions that sustain the existing order (Cox, 1981). So, these theories serve some purpose, which can be to solve the problems in the system or to maintain the balance of power in the world order. As problem-solving theories, their main aim is to solve problems existing among relationships and institutions and help them work more smoothly. When looking at a problem, conventional theories analyze and deal with its source. These theories are inherently conservative and aim to smooth out the whole system by solving some parts of the issue. On the contrary to the conventional theories, critical theory aims to extend human emancipation by understanding the process of historical change. It tries to liberate, practically, human beings from the natural conditions and obligations. It can be said that emancipation occurs through communication and dialogue as well as within economic, social and political platforms (Cox, 1981).

21

CHAPTER 3

TIMELINE OF CLIMATE CHANGE NEGOTIATIONS

This chapter examines the timeline of the international negotiations and policy preferences as well as the discourses of states and attendant mitigation steps. The main actions are COPs which are arranged annually by the UNFCCC to review adaptation and mitigation steps of states and apply new regulations for climate change governance. In here, the literature review mainly includes official information from the UN official website. Also, the summary of the COPs and their reflected outcomes for the commitment issue in the conclusion of this chapter.

3.1. International Initiatives before the UNFCCC

Until the UN established a framework convention, there were different mechanisms that covered many different, specific concerns instead of a constitutive platform that covered international climate change governance in a wholesale fashion. Initially, the 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling was adopted. This convention focused on putting quotas and setting procedures for whaling states. The aim was to preserve stocks of great whales and protect the oceans' nutrient cycle. Later, the International Maritime Organization developed by International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) in 1973. This convention was created to curtail pollutions of the oceans. After MARPOL came the adoption of the Geneva Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (LRTAP) in 1979. The UN Economic Commission operated the LRTAP for Europe. This convention expanded the list of pollutants that should be curtailed and identified specific commitments and steps to address many issues relating to pollution. In 1987, the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer was established to eradicate individual states’ emission of ozone-depleting substances (ODSs). The decisions taken by the authority of the meeting of the Parties, and, while the agreements were legally binding, they could not be enforced.

The first World Climate Conference was in Geneva in 1979, at which the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) was established. The WMO aimed to inform

22

about global warming and its conclusions on earth. It issues that the governments should take steps on preventing artificial changes in climate because of adverse influence on human's lives. So, in November 1988, WMO and UN Environment Programme (UNEP) frame the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The establishment of the IPCC was a groundwork for scientific assessments that enables insights for international negotiations. The IPCC assessments are so necessary for providing an underpinning for making international climate change policymaking. These regular assessments were prepared on a scientific basis and assessed climate change and its impacts, as well as the management of its future risks and policies for mitigation and adaptation. More policy-relevant but not policy-prescriptive, the assessments were meant to serve as projections of present and future scenarios regarding climate change. Discussions about different climate change scenarios offered a status quo or baseline about the current situation, rather than offer concrete suggestions on actions to be taken.

The IPCC is open to all member countries of the WMO and the UN. It currently has 195 members. The panel consists of representatives of the member states gathered in plenary sessions that take significant decisions. The IPCC Bureau, elected by member governments, ensures leadership to the panel on technical, scientific, and strategic issues. These assessments are indeed made by several leading scientists, who serve as volunteers as coordinating lead authors and lead authors, and hundreds of other experts as contributing authors, all of whom support the work recommended in the reports. Transparency and the overall structure are essential parts of the IPCC reports because they are tested in several rounds of analyzing and drafting stages. They contain the scientific, technical, and socio-economic assessments of climate change (IPCC Fact Sheet, 2013). In November 1990, the IPCC offered its first assessment, reporting that "emissions resulting from human activities are substantially increasing the atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases". It subsequently called for a global treaty to be reached at the Second World Climate Conference.

3.2. The Adoption of the UNFCCC and UN Negotiations Timeline

International initiatives have helped make global climate change policies more concrete in practice. In order to ground and structure an international framework, in December

23

1990, the UN General Assembly created the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC). In addition to the WMO' studies, the UN bargains emission targets, binding commitments and financial mechanisms in this first meeting of INC in December 1990. International climate change negotiations have been ongoing since the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, yet global GHGs have increased by one-third since the adoption of the UNFCCC in 1992.

On 5 June 1992, at the Earth Summit in Rio known as the UN Conference on Environment and Development, the UNFCCC developed two sister Rio conventions: the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) and the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (UNCBD). The UNCCD, prepared in 1994, agreed on issues concerning the environment and sustainable land management, characterizing arid, semi-arid and dry lands as vulnerable to climate change. The CBD was a major step forward in working towards sustainable development, protection of biological diversity and its components, and fair usage of genetic sources and their benefits.

The UNFCCC entered into force on 21 March 1994 with a treaty signed by 196 states, known as ‘Parties' in the convention. The signatories agreed to meet annually at conferences known as Conference of the Parties (COP) to discuss recent affairs in climate change and possible responses. The convention separated the Parties into three main groups. The first group was Annex I, which included the industrialized countries, which are also members the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). It included others, too, such as countries whose economies were in transition, the EIT Parties, such as the Russian Federation, the Baltic States, and several Central and Eastern European States.

The second group is Annex II Parties, which include only OECD members of Annex I. Annex II Parties are responsible for providing the financial backing for developing countries to apply emissions-reduction policies under the convention. One of the key aspects of the financial support was the transfer of climate-friendly technologies to the EIT Parties. Other Parties were called Non-Annex I Parties, which contain mostly developing countries. These countries were vulnerable to the dangerous impacts of climate change, including those particularly prone to desertification and drought and which were located in low-lying coastal areas. They were also the group of countries

24

most reliant on fossil fuels for the economies. Specifically, the convention aimed to address their needs and concerns for investment, insurance, and technology transfer. In addition, 49 Parties in the convention were known as least developed countries (LDCs) has named by the UN. LCDs had particular circumstances and were given special consideration under the convention, since they had a limited capacity to adapt to climate change policies. Also, there were disclaimers about the role of observer organizations, which participated in sessions and meetings, but with some specific quotas for admission to conferences.

The first Conference of Parties in Berlin was a leading meeting known as a Berlin Mandate. It enabled Parties to negotiate commitments, especially for developed countries. In August 1996, the UNFCCC moved its secretariat from Geneva to Bonn, a city in Germany known as a sustainable international hub. This settlement of secretariat supported the KP. The first and second COPs were designed to build a roadmap towards the KP.

3.3. The First Treaty on Climate Change: KP

In 1997, an essential step for climate change politics was achieved. The KP was adopted on 11 December at COP3 in Kyoto, Japan and entered into force in 2005 according to Article 23. The adoption of the KP was an essential treaty for the reduction of GHGs, a historical milestone for establishing compulsory emissions reduction targets. According to Article 24, in open signature dates from 16 March 1998 to 15 March 1999 at UN Headquarters, the Protocol received 84 signatures. In Article 22, Parties considered the KP as a piece of the convention regarding future procedures, such as ratification, acceptance, approval, and accession. The Parties that did not sign the KP could, however, decide to participate in it.

The KP was recognized as a sharing burden on developed countries specifically. Developed countries were considered the principal actors historically responsible for dirtying the air with carbon emissions; after all, the industrial activity of developed countries was far greater in the past. The Protocol produced binding emission reduction targets for each Party but slowly on the developed ones. The principle of the Protocol was clear in the meaning of "common but differentiated responsibilities" (UNFCCC,