SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ

YABANCI DİLLER EĞİTİMİ ANABİLİM DALI

İNGİLİZCE ÖĞRETMENLİĞİ BİLİM DALI

THE EFFECTS OF CALL ON THE ACHIEVEMENT OF

7

THGRADE EFL LEARNERS AT PRIMARY SCHOOL

FATMA KÜBRA HARMANCI

YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ

DANIŞMAN

PROF. DR. SELÇUK ÜNLÜ

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all I would like to express my gratitude to all those who have supported and guided me in this thesis but most of all to my advisor Prof. Dr. Selçuk Ünlü for his help, patience, guidance and understanding throughout this study.

I am thankful to Prof. Dr. Erdoğan Şeker for his help in the statistics and data analysis of the research, for his suggestions and guidance.

I also would like to thank to my friends Aynur Yurdanur Altunay, Mustafa Ginesar and Ali Güven, who helped me in conducting the study, for their cooperation, friendship and support.

My biggest thanks go to my family without whom this thesis would be impossible to complete. They were understanding, encouraging and caring all the time. I am especially very grateful to my father, Ömer Harmancı, to my mother, Şerife Harmancı and to my brother for their being very supportive and patient during the thesis and my whole life. I will always appreciate their caring and support which gave me the great desire to go on.

ABSTRACT

Due to the developments in information technology, many studies have been conducted in the field of education. As a contemporary approach, Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) is one of those rapid developments which have a vital role in English Language Teaching (ELT).

The purpose of this study is to search the effects of Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) on the 7th grade EFL students’ achievement in learning English at a primary school by determining whether there is difference between the use of computer assisted presentation material in addition to classroom teaching and traditional teacher centred language teaching.

The study was applied during the 2007-2008 academic year and presented to 7th grade students in Konya Cihanbeyli Merkez Atatürk Primary School for 10 weeks. Two groups of students participated in this research. Adaptive with the 7th grade syllabus, the experimental group studied the target structures via computer assisted presentation material in addition to classroom teaching, while the control group studied the same target units with traditional methods. In order to gather the necessary data for the study, a multiple choice test was prepared and applied to determine the achievement level. The test was standardized with the reliability coefficient of α = 0, 8046 and 40 questions were used respectively. This study was executed according to the pre-test, post-test and recall-test (after 8 weeks), one test and one control test model. The data results that belong to the tests are evaluated by independent group’s t-test analysis model of SPSS.

At the end of this research it is stated that in teaching English, Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) is effective and computer assisted presentation model increases the achievement in a significant level (P < 0.005) when it’s

compared with classical teacher-led traditional methods. It is also indicated that there isn’t a meaningful difference in the level and test results of recall (P > 0.005). This result shows that the students didn’t forget the target units because of the repetitions of the same structures in the following non-target units and exercises performed by ever so often intervals. Moreover, these following non-target units made the students promote their knowledge level.

Key Words: Computer Assisted Language Learning, Computer Assisted Presentation Material, Traditional Teacher-Centred Language Teaching

ÖZET

Bilişim teknolojisindeki gelişmelerden dolayı eğitim-öğretim alanına da pek çok çalışma yön vermeye başlamıştır. Çağdaş bir yaklaşım olan Bilgisayar Destekli Dil Öğrenimi, İngilizce Dil Öğretiminde çok önemli bir role sahip olan bu hızlı gelişmelerden biridir.

Bu çalışmanın amacı, sınıf içi öğretime ek olarak bilgisayar destekli sunum materyali ile geleneksel öğretmen merkezli dil öğretimi arasında fark olup olmadığını belirleyerek Bilgisayar Destekli Dil Öğreniminin İngilizceyi yabancı dil olarak öğrenen ilköğretim 7. sınıf öğrencilerinin başarılarına olan etkilerini araştırmaktır.

Çalışma; 2007 – 2008 öğretim yılında evrenini Konya il merkezinde bulunan ilköğretim okulları, örneklemini Cihanbeyli ilçesi Merkez Atatürk İlköğretim Okulunun 7. sınıf öğrencileri oluşturmak üzere 10 hafta boyunca uygulanmıştır. Araştırmaya iki grup katılmıştır. 7. sınıflar müfredat programına uyumlu olarak belirlenen hedef dil yapılarını, kontrol grubu geleneksel dil öğretim metotlarıyla öğrenirken, deney grubu aynı hedef dil yapılarını sınıf içi öğretime ek olarak bilgisayar destekli sunum materyali ile çalışmıştır. Çalışma için gerekli verileri elde etmek amacıyla 50 soruluk çoktan seçmeli bir ölçme aracı hazırlanmış ve başarı seviyesini belirlemek için öncelikle 8. sınıflara uygulanmıştır. Öğrencilerin başarı düzeylerinin belirlenmesinde güvenirlik katsayısı α = 0, 8046 olarak hesaplanıp çoktan seçmeli İngilizce başarı testi soru sayısı 40’a indirilerek standart hale getirilmiştir. Çalışma, ön test – son test ve 8 hafta sonra uygulanan hatırlama testi ile bir deney – bir kontrol deneme modeline göre yürütülmüştür. Başarı düzeyini belirlemek amacıyla uygulanan testlere ait veriler, SPSS paket programından yararlanılarak, bağımsız gruplar t-testi analiz modeliyle değerlendirilmiştir.

Araştırma sonunda, İngilizce öğretiminde Bilgisayar Destekli Dil Öğreniminin etkili olduğu ve öğretmen merkezli geleneksel öğretim metotlarıyla karşılaştırılınca bilgisayar destekli sunum modelinin başarıyı önemli bir düzeyde (P < 0.005) artırdığı ifade edilmiştir. Aynı zamanda hatırlama testinin sonuçları ve seviyesinde anlamlı bir farklılık görülmediği de belirtilmiştir. Bu da, İngilizce müfredat programına göre hedef konuların devamında işlenen hedef olmayan ünite ve konularda da benzer dilbilgisi yapılarının tekrar edilmesi ve alıştırmaların sık aralıklarla yapılması sebebiyle öğrencilerin konuları ve hedef davranışları unutmadıklarını göstermektedir. Hatta hedef olmayan bu devam konuları öğrencilerin bilgi seviyelerini yükseltmelerini, geliştirmelerini sağlamaktadır.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Bilgisayar Destekli Dil Öğrenimi, Bilgisayar Destekli Sunum Materyali, Geleneksel Öğretmen Merkezli Dil Öğretimi

TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……..………i ÖZET…..…………..……...………..……iii ABSTRACT..………...……….……….………v TABLE OF CONTENTS………...………...vi LIST OF TABLES………...………... .x LIST OF FIGURES………...………..xi CHAPTER I 1. INTRODUCTION 1.0. Presentation………...1

1.1. General Background to the Study…………..…………....…..…..……..1

1.2. Goal and Scope of the Study………..………..…………...3

1.3. Statement of the Problem………...………....….5

1.4. Method of the Study………...………...7

CHAPTER II

2. REVIEW OF LITERATURE

2.0. Presentation………...………...10

2.1. A Short History of Computer – Assisted Language Learning……..10

2.2. Scope of Computer – Assisted Language Learning……..……..…..17

2.3. The Roles of Computers in Second / Foreign Language Learning...24

2.3.1. Motivation ………28

2.4. The Roles of Teacher in CALL Lessons………...29

2.5. Advantages and Limitations of CALL………..34

2.5.1. Advantages ………..34

2.5.2. Limitations ………...37

2.6. Computer – Assisted Language Learning Applications…………...39

2.6.1. Computer and Grammar………..……….42

2.6.2. Computer and Vocabulary………....………43

2.6.3. Computer and Reading………...44

2.6.4. Computer and Listening………...46

2.6.5. Computer and Writing……….………....48

CHAPTER III

3. METHOD OF DATA COLLECTION, ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION OF THE RESULTS

3.0. Presentation………...53 3.1. Subjects…...……….53 3.2. Assessment Instruments……..……….………54 3.3. Procedure…..………...57 3.4. Assumptions……….………...60 3.5. Limitations……….……….61

3.6. Data Analysis and Interpretation of the Results……….62

3.7. Conclusion………..67

CHAPTER IV 4. CONCLUSION 4.1. Summary and Findings………..69

4.2. Recommendations……….70

REFERENCES………...72

APPENDICES………78

Appendix I………78

Appendix III……….88 Appendix IV………89 Appendix V……….90 Appendix VI………91 Appendix VII………...92 Appendix VIII………...…..93 Appendix IX………...….94 Appendix X………...…..95 Appendix XI………..….96 Appendix XII………...…...97 Appendix XIII………..……..98 Appendix XIV………..…..99 Appendix XV………..…..100

LIST OF TABLES

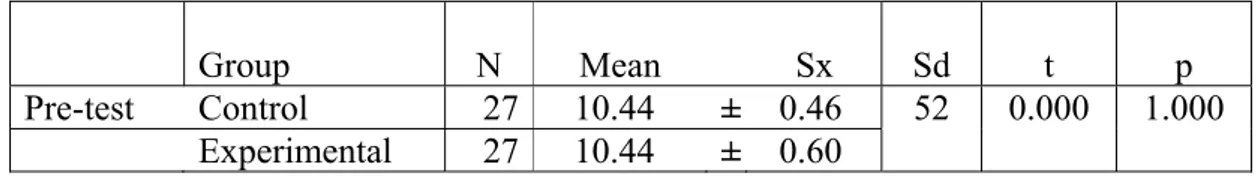

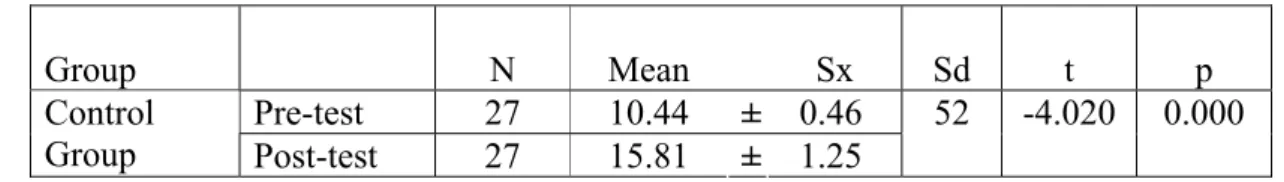

Table 3.1. The Sex Distribution of Subjects in the Study……….54 Table 3.2. Reliability Analysis for Pre – Post and Recall Tests………....56 Table 3.3. Means and Standard Deviations for the Pretest for Experimental and Control Group………62 Table 3.4. Means and Standard Deviations for the Post-test for Experimental and Control Group……….63 Table 3.5. Means and Standard Deviations for the Recall-test for Experimental and Control Group……….63 Table 3.6. Means and Standard Deviations for the Pre-test and Post-test for Experimental Group………...64 Table 3.7. Means and Standard Deviations for the Pre-test and Recall-test for Experimental Group………..….64 Table 3.8. Means and Standard Deviations for the Post-test and Recall-test for Experimental Group………...65 Table 3.9. Means and Standard Deviations for the Pre-test and Post-test for Control Group………....65 Table 3.10. Means and Standard Deviations for the Pre-test and Recall-test for Control Group………....66 Table 3.11. Means and Standard Deviations for the Post-test and Recall-test for Control Group………....66

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 2.1 CALL and related disciplines………..18 Figure 2.2. Common Types of Programs Used in CALL……….40 Figure 2.3. Pedagogical Description of CALL Programs and

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

1.0. Presentation

This chapter provides an overview of this study including the background to the present study, goal and scope of the study, statement of the problem, method of the study and key terminology.

1.1. General Background to the Study

In today’s world, computers are used in teaching languages, drawing maps and graphs, keeping track of manufacturing orders, preparing timetables for trains or aeroplanes. Actually, they have become an integral part of our lives whether we’re scientists, linguists, businessmen or learners. In fact, computers have become the giant brains on which large parts of modern society depend.

The reason people use computers is because computers can do certain necessary or desirable tasks more effectively than people. Computers can also permit people to do things which were not previously possible. Computers are quite powerful tools for learning language. As Philips (1987: 26) states: “Just as the lever is a device which compensates for the limitations of human muscle power, so is the computer a device which compensates for the limitations of brain power”.

As the use of computer-based technology takes its place in the education system, computer-assisted language learning (CALL) may provide new opportunities for applying audio-visual, cognitive and communicative approaches which support the learning of new skills more effectively than classical methods of language

teaching. Moreover, teachers who are aware of CALL can benefit from this technology by improving their teaching techniques, rather than continuing to rely on classical methods in classes. At the same time, experienced teachers may be afraid of using this technology in the classroom because they are not familiar with the technology, while newer teachers are more confident, because they might have had experiences in using computers when they were students (Bebell, O’ Conner, O’ Dwyer & Russell, 2003; Smith, 2003).

In every kind of education system, to teach learners well has been the main aim. With what to teach and how to teach have been extremely important, and the answer has been pointed out computer. Educators are becoming more aware of using new technologies in the classroom, especially in the field of English Language Teaching. Computer – Assisted Language Learning (CALL) is a rapidly expanding field and some comments build up the growth of interest in this field, as Pennington (1996:1) puts it: “CALL promotes a better learning/teaching process.”

Computers can be splendid useful tools for English language learning/teaching. They can process user input quickly, and integrate voice, music, video, pictures, simulations and animations together with texts into lessons. They can be programmed to tailor instruction and tests for each individual learner according to their needs. They can even make students feel more comfortable and willing to take risks, because of their “untiring, unjudgmental nature” (Butler-Pascoe, 1997:20).

CALL is becoming widespread in schools and for language teaching. As mentioned in EARGED (1999), computers have been used for various functions in the field of education. One of the functions of computers in education is its usage as a tool of lesson presentation. In education programs, if possible the entire or partly, the contents and subjects of lessons have been presented to learners via computers. Many institutions are attempting to find ways of integrating CALL into their curricula. Also, computers have been used as a private teacher independent from

classroom environment in education. In this method a specific unit or subject of a lesson has been thought to learners through computers and computers take on the function of private teachers. Moreover, teachers who are aware of CALL can benefit from this technology by improving their teaching techniques, rather than continuing to rely on classical methods in classes.

Brosnan (1995) suggests that students today are in the middle of an explosion of academic information. They can assume more responsibility for their own learning through computer technology. Moreover, they have the opportunity of exploring areas of interest and discovering their own learning styles by studying on their own in a way that seems more fun than traditional methods. In addition, the teachers that are aware of the opportunities that CALL brings may explore their teaching styles.

1.2. Goal and Scope of the Study

The goal of this study is to search the effects of Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) on the 7th grade EFL students’ achievement in learning English at a primary school by determining whether there is difference between the use of computer assisted presentation material in addition to classroom teaching and traditional teacher centred language teaching.

Computers are one of the leading teaching materials in our age. They help arranging teaching – learning environments by taking learners’ attention to the learning procedure and facilitating the learning. Some of the contributions of computers in learning environment are;

“1. They increase the students’ interest and learning intention and motivation in a learning and teaching environment.

3. They support unlimited repetition and practice.

4. They enable the development of upper-level skills of students’ learning. 5. They promote collaborative learning” (Kaptan, 1999: 63).

Considering these assumptions Senemoğlu (1997) indicates that computer – assisted learning effects especially the achievement of primary school students highly, secondary school students in a medium level and university students in a low level.

The thesis intends to help answer the questions such as why computer is important in language learning and teaching, what these factors are, what are the roles of computers and teachers in the learning process, why teaching and learning become more effective and fruitful in CALL rather than teacher – centred language learning, why the language learners learn differently in computer – assisted language classes and in teacher – centred language classes, and is computer the best educational aid in language learning and teaching.

Our aim is to find out whether computer – assisted presentation model in addition to classroom teaching in language learning is beneficial and effective for the achievement of EFL students against the traditional methods or not.

1.3. Statement of the Problem

The problem recognized by the language teachers and learners alike is that language teaching based on traditional methods and using audio/visual materials do not always meet the needs and increase motivation. Therefore, we must look for innovative ways of teaching our course material using new technological advancements. Technology is penetrating into education and the use of computers in the teaching/learning process may correspond the demands. So the primary question is whether using computer-assisted presentation material is effective rather than the traditional teaching methods.

Many researchers report a number of benefits for students related to the general use of computer technology in classrooms. These benefits include mastery of basic skills, increased motivation, improvement in self-concept, more student – centred learning, more active participation, more equal access to teacher interaction, and more engagement in the learning process, resulting in higher-order thinking skills and better recall (Brownlee-Conyers, 1996; Dwyer, 1996; McGrath, 1998; Weiss, 1994).

However the use of computers in language classrooms is a recent innovation in Turkey. State and schools have already started using computers in both administrative and educational settings. Some governmental organizations have also taken initiatives in order to establish CALL or multimedia laboratories in their educational training departments (Selçuk, 1995). In Turkish educational institutions educators witnessed a substantial increase in the exploitation of computer-mediated and enriched instruction in second/foreign language education, as the properties of computers are potentially enhanced in the long run.

A significant step about integrating CALL into the curriculum and learning English by the help of courseware was taken by the Turkish Ministry of Education. The ministerial office signed a protocol for a software program called DynEd, in April 2006, between Sanco, Inc. and Future Prints Computer Industry and Trade, Inc. Besides Turkey, France’s and China’s Ministries of Education have approved the same courseware program. “DynEd”, which stands for “Dynamic Education”, has research-based courses covering all proficiency levels and include a range of age-appropriate courses, from kids in school to adults in leading corporations. In addition, DynEd courses are supported by Records Management System and Mastery and Placement tests for feedback. Having been approved in 2006, it has been actively used in primary and secondary schools of Turkey.

However, the software has some handicaps during the implementation. First of all, each school needs a computer lab or enough number of computers for students. Secondly, the hardware and software of computers should have a proper level, for instance, the operating system should be or over Windows 2000 and XP at least. Finally, the schools must have internet connections to install DynEd software and use the program. When we consider the conditions and layouts of public schools in Turkey, we can say that it cannot be easily implemented and practiced by some schools, especially in rural areas.

Since this thesis is an experimental study of CALL through lesson-presentation aimed treatment (or we can say computer – assisted presentation model) by measuring the effects and permanency on students’ achievement, it will certainly contribute to CALL literature in second/foreign language teaching in Turkey. Thus, this thesis is intended as an introduction to computer-assistant language learning rather than computers. No knowledge of programming is assumed. Answers of the following questions are investigated:

1. Is there any difference in terms of post-test, in the target units, between the test group who have studied computer-assisted presentation model in the computer

lab in addition to classroom teaching and the control group who are taught by traditional methods in a teacher-centred classroom?

2. Is there any difference in terms of recall test of students’ achievement level, in the target structures, between the test group who have studied computer-assisted presentation model in the computer lab in addition to classroom teaching and the control group who are taught by traditional methods in a teacher-centred classroom?

1.4. Method of the Study

The study was applied during the first term of 2007-2008 years of study and presented to 7th grade students in Konya Cihanbeyli Merkez Atatürk Primary School. For this experimental study, it was necessary to learn the subject and then prepare a pre-test accordingly. As a subject matter, the first three units of 7th grade syllabus are chosen. The experimental material is designed and formed with the software of Microsoft Office PowerPoint 2003 presentation program. The subjects of the structures are “Verb to Be Present & Past, Simple Past Tense, and Comparatives of Adjectives”. The pre-test was a multiple choice test consisting of 50 questions related to the structures through fifteen target behaviours that students are expected to achieve. The test was applied to 8th grade students at the same school to determine the achievement level. The reliability of the pre-test was measured by the program SPSS-10. Ten questions were eliminated as a result of this reliability test. After the elimination of some questions, the achievement test was standardized.

Secondly, the students were divided into two groups as experimental (test) and control groups. Both groups were given a pre-test as an English Achievement Test, standardized with the reliability coefficient of α = 0,8046, consisting of fifteen target behaviours and including 40 questions related to the structures respectively. Then the control group was taught with traditional teaching methods by the language teacher while the experimental group studied the same structures with the computer assisted presentation material in addition to classroom teaching by the guidance of the same

language teacher and a computer teacher. This study process took 10 weeks (four hours for each week). After the teaching period, the pre-test was applied to the same students as a post-test.

Finally, eight weeks later, both experiment and control groups were given a recall test, the same as the pre and post tests, to measure the effects and permanency of the structures studied according to the one experiment and one control test model. The data results that belong to the tests are evaluated by independent group’s t-test analysis model of SPSS-12.0.

1.5. Key Terminology

A number of field-specific terms are employed throughout this research. It will be quite useful to provide brief definitions of these terms.

Computer Assisted Instruction (CAI): The application and practice of using computers in education as an instructional tool. The term ‘instruction’ emphasizes the teaching or tutorial role of computers.

Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL): The application and practice of using computer in second/foreign language education as a learning tool. The acronym has been the most standard one in the literature, “a term designating both software and Internet enhanced approaches” (Hanson-Smith, 2000 as cited in Arkın, 2003: 9).

Computer Literacy: As accepted by Computer-Assisted Instruction specialists, computer literacy is the knowledge about computer applications and experience in the learning process. In addition, the actual use of computing skills for

real life problem-solving and knowledge of the role of computers in society are a part of computer literacy.

Courseware: A general term which is used for the developed computer assisted instruction/learning materials. A CALL/CALI lesson is some courseware, educational software or program; however, a computer program, or some educational software is not necessarily courseware.

Hardware: It’s a general term which is used to refer to the physical elements of any computer system, such as monitor, keyboard, mouse, and printer.

PowerPoint Presentation Program: A popular Microsoft presentation software product allowing a user to create dynamic and audiovisual demonstrations, slides, handouts, notes, and outlines incorporating photos, clipart, charts, graphs and text (displayed on a computer monitor or through a projector). The relevant points to the entire presentation are put on slides to accompany speeches for instructional purposes.

Software: It’s a general term which is used to refer to programs, applications, or various system files, by which the computer is instructed to perform specific tasks.

Word-processors: The term has been used to refer to an electronic device which is devoted to the manipulation of text. It usually includes a keyboard, a display screen and some means of storage. The process of working a word-processor is referred to as word-processing.

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

2.0. Presentation

This chapter gives a brief account of the history and scope of CALL. A critical discussion of the roles of computers in second / foreign language learning, roles of the teachers, advantages and limitations of CALL as well as CALL practice and main computer applications in language learning are handled out.

2.1. A Short History of Computer – Assisted Language Learning

“Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) may be defined as “the search for and study of applications of the computer in language teaching and learning”. The name is a fairly recent one since the existence of CALL in the academic literature has been recognizable for about the last thirty years. The subject is interdisciplinary in nature, and it has evolved out of early efforts to find ways of using the computer for teaching or for instructional purposes across a wide variety of subject areas, with the weight of knowledge and breadth of application in language learning ultimately resulting in a more specialized field of study” (Levy, 1997:1). The first use of the computer for instructional purposes was the Whirlwind Project, unveiled at MIT in 1950, and designed as a flight simulator to train combat pilots. It is noteworthy, therefore, that the first use of the computer for educational purposes was a simulation, which substituted for a reality that was potentially costly and dangerous (Levy, 1997).

A review of the published literature on the area indicates that CALL has been practiced in some form since 1960s, although the common term used was not CALL

but CAI (computer – assisted instruction) and CBI (computer – based instruction). In early years, mainly in the United States, before microcomputers increased in number, work on computers and CALL was almost completely limited to college language departments that usually had access to mainframe computers. Furthermore, people who worked with large computer systems tended to feel that a complete CAI system might be an alternative to traditional classroom instruction, rather than a technological supplement and contribution to education large (Underwood, 1984: 41). This tendency is observed to have been mainly a consequence of programmed instruction, which was the most popular pedagogical development during the 1950s and 1960s in the United States.

Based on Skinner’s (1954, cited in Rivers, 1981: 111) behaviourist theory of operant conditioning, programmed learning implied that “a body of knowledge can be reduced to a set of very small steps, each of which is easily learnable. Each step is turned into a “frame” which contains a line or two of exposition and a comprehension question”(Higgins, 1985: 34). Thus, the adherents of this pedagogy stressed “minimal steps”, “individual learning pace” and “immediate feedback” as the three important principals of programmed instruction. Although books, tapes and similar materials were the main media of applying these principals, educators soon came to realize that computers could be well used to present learners any body of knowledge or information through discrete steps turned into small frames. With the proliferation of computers and language educators’ interest in programmed learning, the early experiments with CALL were closely and intellectually linked to Skinner’s theory of operant conditioning and programmed learning. In other words, CALL can be said to have emerged from programmed learning and behaviourist techniques of instruction.

The period between the late 1960s and the early 1970s can be considered particularly important for the historical development of CALL in the United States. It was during this period that computer technologies rapidly developed and that

linguists and literary researchers also became interested in using computers, which then gave way to the introduction of computers in foreign language teaching and learning. Ahmad et al.(1985: 28-34) distinguish between four important CALL projects that were developed and implemented during the late 1960s and the early 1970s, which are the Stanford Project, the PLATO Project, Work at Dartmouth and the Scientific Language Project.

The first project was developed under the supervision of Van Campen (1973) in the Slavic Languages Department at Stanford University. The project was, in nature, a self-instructional computer-based introductory Russian course in which the CALL materials were mostly presented within the format of programmed instruction. In this Russian course, learners had to type answers to questions given in Russian, to inflect words, and to do a variety of transformation exercises. The students on this project also participated in traditional language laboratory exercises, and twice a week they made recordings, which were later evaluated by their teachers.

The Programmed Logic for Automated Teaching Operation (PLATO) system was another computer-based education project which was developed at the University of Illinois in the 1970s. As Ahmad et al.(1985: 30-31) report, the PLATO system was aimed at servicing the needs of computer-based education for a variety disciplines taught at a conventional university. The system consisted mainly of computers and terminals manufactured by a computer company, together with some special purpose software to develop CAI materials, which can only be run on the company’s special hardware. As in the Stanford project, the CALL part of the PLATO system focused on Russian. However the CALL activities were carried out mainly to teach students to translate written texts from Russian to English. Reading and grammar were taught only as aids to translation. In addition Curtin et al.(1972) are referred to as the first language teachers who used the PLATO system for foreign language teaching. Reportedly, their Russian courses included three important components of a CAI course, which are vocabulary drills with relevant explanations,

short grammatical explanations and drills, and translation tests given at different periods. Then a final translation test was given to determine to what extent the students had comprehended written Russian. As a result, the CALL courses at the University of Illinois became successful, and the results of the Stanford Introductory Russian course were really encouraging.

In the meantime, the late 1960s were also witnessing another CALL project at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. As one of the first academic institutions that serviced its users a time-sharing system, the college developed the BASIC programming language (Beginners All Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code), and various computer-supplemented language teaching materials were prepared in BASIC. Waite was among the first language teachers who used the Dartmouth time-sharing system in 1970 and who provided supplementary CALL materials for the teaching of Danish, French, German, Latin, Spanish, English and Russian. All the CALL activities were mostly characteristic of fill-ins and vocabulary drills in addition to the later writing activities which were aimed at developing the correct use of punctuation, colon and semicolon. Like those which were developed in the PLATO system and the Stanford Project, Dartmouth College’s CALL programs were also in the format of programmed instruction which emphasized that students would absorb small learnable frames on their own pace through immediate feedback mechanisms (Öz, 1995).

The last project on the way to the establishment of CALL is the Scientific Language Project which was conducted at the University of Essex between 1965-1969. Referring to Alford (1971), Ahmad et al. (1985:33) report that this project was “designed to provide computer assistant in reading specialist texts in Russian. People who most benefited from the project were researchers and academics in science and in engineering.

Coburn et al. note that in the sixties “with much fanfare an ‘educational revolution’ was declared, although its actual realization always seemed just around the corner” (1984: 233). Also, despite several millions of dollars spent on some pilot projects, CAI did not become efficient and popular. A number of reasons are given by Coburn et al. for such failure:

- The cost of the hardware and software was too high.

- Teachers were not eager to use the computers in education. They feared the loss of their jobs.

- There was no efficient organization to introduce the computer materials into the schools and to train the teachers.

- The effectiveness of CAI was mostly exaggerated.

- Since schools are conservative institutions they did not want to adopt the new methods without being sure of their effectiveness (1984: 234).

It was not until the late 1970s, when the first popular microcomputers appeared, that any significant attempts were made to introduce CALL to a wider audience (Davies & Higgins, 1985). Coburn et al. point out that “The relatively low cost, portability, reliability and friendliness of microcomputer systems have overcome many of the objections that were fatal to educational computing in the sixties and seventies” (1985: 241). TICCIT (Time-Shared, Interactive, Computer-Controlled Information Television) was developed in 1972 and this minicomputer-based system was intended originally for teaching mathematics and English courses to college freshmen (Bitter, 1989). Like PLATO which used a special authoring language called TUTOR, TICCIT also used an authoring system so that users could create their own software. TICCIT also included a colour television and sophisticated graphics. TICCIT attempted to present concepts and to teach the use of rules rather than presenting drill and practice activities as well as giving the learner control over the lesson (Bitter, 1989). Bitter notes that many groups have formed to develop theories and materials in teaching with computers. The Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium (MECC) was one of those groups, formed in 1972, tried to

improve the use of computers in education. MECC began to develop software with a reputation for excellence and reasonable cost. Another group dedicated to improving the use of computers in education is WICAT (the World Institute for Computer-Assisted Teaching); formed in 1977, WICAT was created to develop high quality software for teaching basic skills such as reading and mathematics (Bitter, 1989). In 1977, the Micro-PLATO system was introduced, reflecting the trend of educators toward smaller computer systems.

The development of computer languages, for example, PASCAL and C, enabled computer programmers to create some powerful hypermedia multimedia authoring languages and systems like Course Builder, HyperCard, MacAuthor, and Video Builder. These authoring tools, the characteristics of which are mentioned by Cook (1989: 109-122), in turn enabled educators and also language teachers to involve in developing educational courseware. More importantly, using the available programming languages, authoring languages, and authoring systems, language teachers can now develop a variety of CALL materials and provide various activities for their students.

There is no question that Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL) has come of age. Computers have been a feature of teaching and learning of Modern Foreign Languages (MFL) since the 1960s in higher education and since the early 1980s in secondary education. The rapid growth in the 1980s led to the foundation of the two leading professional associations: CALICO (USA) in 1982 and EUROCALL (Europe) in 1986, both of which continue to thrive and now form part of the WorldCALL umbrella association (Davies, 2003). The articles on CALL have appeared in some EFL journals: Computer Assisted Language Learning, SYSTEMS in Britain; CAELL (Computer Assisted English Language Learning) Journal, CALICO (Computer Assisted Language Instruction Consortium) Journal, several newsletters in the USA; ON-CALL in Australia; MUESLI (Micro Users in ESL Institutions) News, and the newsletter of the CALL special interest group, which is

distributed to interested members of IATEFL (International Association of Teachers of English as a Foreign language) (Higgins, 1996).

The advances in microcomputer technology started work on “artificial intelligence” towards the end of the eighties. According to the goals of artificial intelligence, the computers will be able to reproduce the human intelligence and communicate easily with the users in natural language. But while such work is continuing there is still a dearth of programs which will meet learners’ needs and expectations (Özmen, 1990:18).

“Programs written in the 1980s illustrated the imagination skill of language teacher-programmers as well, perhaps, as their limitations, in the size and complexity of their programs. At this time language teachers had the opportunity to become closely involved in the conceptualization of their programs, and their input needs to be retained at every level in the more team-oriented efforts of the 1990s. Over the last decade authoring programs have become more user-friendly and more powerful even allowing multimedia interactions to be programmed with relative ease” (Levy, 1997: 43). The introduction of interactive multimedia is the most apparent change during the 1990s due to the advances in computer technology. The term multimedia means that more than one medium of communication is employed to deliver a message. Multimedia presentations may combine video, sound, graphics, still photography, animation and text (Kanning, 1994). The ability of the computer to provide video and audio in combination with text is an important advance that has implications for the development of the computer-based language-learning programs (Brett, 1996).

Wolfe reported a number of issues to achieve effective use of computers in language teaching and made some predictions about what might happen in educational technology in the 21st century such as “Textbooks will be converted into CD-ROM (Compact Disc Read Only Memory) like discs about the size of a dollar

coin which will be played on a portable CD player. Feature-length foreign language films of two hour duration will be available on a disc the size of our current CDs. The disc will be erasable and can be recorded over” (Wolfe, 1993: 183).

He mentions the foundation of the National Center for Computer Assisted Language Learning in Canada. The most significant trend of the 1980s for Holmes (1990) was the growing number of CALL developers and even the greater number of users of it, another significant event was the first Canadian on CALL which indicated that the pioneer’s feeling of isolation had finally disappeared.

2.2. Scope of Computer – Assisted Language Learning

In this section the scope of CALL is considered in terms of its relations to other disciplines, its contributions and applications to language teaching, and its research areas. An attempt is made to show the theoretical foundations of the area by discussing interdisciplinary ties between CALL and other areas and touching on CALL activities briefly, followed by common types of research related to CALL.

“CALL is a relatively new, interdisciplinary field of study that has been subject to the influence of a number of other fields and disciplines. In addition to the fields of computing and language teaching/learning, which one would expect to have an impact on CALL, real or potential influences in the development of the field have included elements of psychology, artificial intelligence, computational linguistics, instructional technology and design, and human-computer interaction studies. Many of these disciplines are relatively new in themselves, having developed very significantly since World War II; they each have their own perspective and frame of reference, they often overlap and interrelate, and the extent to which any one should influence the development of CALL has not been determined” (Levy,1997: 47).

CALL, as an interdisciplinary area of study, has been shaped to a large degree by developments in other disciplines and, of course, the development of technology itself. Many of the difficulties faced by CALL practitioners have been encountered by those working in other areas also. To understand CALL and to circumscribe its field of view, therefore, it helps to appreciate the interplay of CALL with other, contributing disciplines. This overview has looked at the influences on CALL of psychology, artificial intelligence, computational linguistics, instructional technology and design, and human-computer interaction studies. The principal avenues of effect on CALL and between the disciplines are illustrated by Levy as:

Figure 2.1 CALL and related disciplines

Resource: Levy, 1997:72.

Such interdisciplinary endeavours have given way to different approaches adopted by the scholars of different disciplines. One approach, for example, which

Human-Computer Interaction Psychology Artificial Intelligence Computational Linguistics CALL Instructional Technology and Design Applied Linguistics

Chomsky (1972) adopts is that linguistics can best contribute to the understanding of human mind and should thus be considered as a branch of psychology. On the other hand, Halvorsen (1988: 202) argues that “computational linguistics is best viewed as a branch of artificial intelligence”. A more extreme argument comes from Matthews (1992), who places CALL into artificial intelligence under the name of “Intelligent CALL”.

For language teaching methodology, there are a number of approaches or methods that have become the foundation for classroom teaching over the past few decades, but these are grouped by Hubbard (1992) as “behaviourist”, “explicit learning” and “acquisition” approaches. While behaviourist approaches are characterized by a view of language as a habit structure and grammar as patterns to be drilled to the point of over-learning; explicit learning, or cognitive code, approaches are characterized by deductive learning of rules of grammar and usage. Including communicative and humanistic approaches, acquisition approaches are characterized by exercises focusing on communicative function of language, realistic interaction and inductive learning.

The use of computer software programs as supportive materials in classrooms provides new opportunities for applying an audio-visual approach, cognitive approach, and communicative approach. While applying an audio-visual approach, pronunciation is stressed, lessons with dialogues are utilized, and mimicry and memorization are used. In a cognitive approach the instruction is often individualized, so students are responsible for their own learning. While using a communicative approach, the goal of language teaching is learner ability to communicate in the target language (Celce-Murcia, 2001). These approaches integrated in software programs support new learning skills more effectively than classical methods for language learning.

According to a methodological framework for CALL which has been proposed by Hubbard (1992), CALL courseware development involves systematic ties between linguistics, psychology and language pedagogy on a theoretical basis. Hubbard adopts Richards and Rodgers’ (1986) methodological framework of language teaching approaches and methods in a dynamic way. The proposed model includes similar views of Approach, Design and Procedure in Richards and Rodgers’ (1986). First, linguistics provide a body of linguistic assumptions for CALL and courseware development, which answers these basic questions as exemplified in Hubbard’s (1992: 42) words: “Is the grammar of a language governed by patterns and analogy or by rules? Is language knowledge fundamentally structural, functional or both? Is the sentence the fundamental unit of language, or are phrases and discourse structures fundamental? Are syntax, semantics, and lexicon separable components of a language or inseparable?” Obviously linguistics provides CALL with a set of theoretical background on which call materials and applications are and should be based (Öz, 1995)

The learning assumptions underlying CALL courseware development is the second important point. In the original model Richards and Rodgers (1986: 8) point out the importance of psycholinguistic and cognitive processes involved in language learning and the conditions necessary for the activation of these processes. Similarly Koç’s (1991a, 1991b, 1993) model of CAI/CALL courseware development reveals the scope of CALL more elaborately. He accounts for the relationship between theories of linguistics/educational psychology and CALL in a dynamic way using a top-down model based on Bloom’s mastery learning. Unlike Hubbard (1992), Koç states that CAI/CALL should also take into consideration institutional needs/national policies as well as societal needs. It thus seems that CALL is also tied with social and political structures of countries.

According to Öz (1995), the last discipline that CALL has intellectually become tied with is Artificial Intelligence (AI), which is generally accepted as a

branch of “Cognitive Sciences” in recent years. However, Underwood (1987a: 198) considers AI as a science somewhere on the border between psychology and computer programming, dedicated to developing techniques for solving intellectual problems. One of the most important contribution of AI to CALL is in fact to be found in the application of its techniques to CALL programs that would normally require intelligence if accompanied by a human. So, AI techniques have been mostly used in machine translation and other programs such as puzzles and chess games that would normally require human intelligence. Due to the advances in technology, in recent years, some simulation programs and games for CALL have been developed on the basis of AI techniques. In Australia, as cited by Lian (1991), the EXCALIBUR project is under development to provide a favourable development and delivery framework for computer-assisted learning (CAL).

“CALL is-and must be-considered as an aid to “in-and outside-the classroom” language education, learning and practice. The main bulk of this contribution includes traditional activities such as cloze exercises, comprehension exercises, dialogs, dictation, gap-filling exercises, grammatical manipulation and vocabulary learning, and more communicative applications like simulations, communicative games, text manipulation and text generation programs” (Öz, 1995: 25).

As for CALL research practices, Pederson (1987: 99-131) distinguishes between three major concerns of the current CALL research: a) Comparative Research Studies, b) Evaluative CALL Research, and c) Basic CALL Research, which is further categorized as Experimental Research, Ethnographic Research, and Formal Surveys. While a comparative research discusses the roles of any two media by investigating differences in achievement and other variables such as attitudes, an evaluative study is a form of applied research which provides “explanatory principles for learning differences that emerge from ethnographic observations or controlled experiments; the purpose of applied research is to achieve practical objectives, i.e. solving problems, in a specific learning situation or with a specific set of learning

materials” (Pederson, 1987: 108). On the other hand, the purpose of Basic CALL research is to discover something about the way students best learn a second/foreign language.

According to Pederson (1987: 115) the experimental type of basic CALL research tries “to investigate the effect of the existence or manipulation of independent variables (learning styles, aptitude, learning task, and the coding elements of the computer) upon dependent variables (achievement or attitude).” In an ethnographic study, however, the researcher goes into the language classroom or the “learning resource centre” to relate learning patterns and variations to previous second language education research. Formal Surveys are Pederson’s last type of basic CALL research; the purpose of such surveys is to identify “special needs, frustrations, misconceptions, and other useful information” (Transferred by: Öz, 1995: 26).

As a scope of CALL research, Chapelle and Jamieson (1991: 37-59) put forward two different paradigms under the names of “Quasi-Experimental Research” and “Descriptive Research”. In CALL research a quasi-experimental design attempts to investigate the effect of CALL on students’ developed language proficiency, for example whether language proficiency of students who use CALL improves, and whether this development can be attributed to CALL activities. Because of the difficulties “in accounting for all the factors affecting students’ performance on language measures” in experimental studies, within the scope of CALL agendas, “researchers have attempted to access the effectiveness of CALL by determining students’ attitudes toward CALL, and by examining the language and strategies students use while they are working on CALL materials” (1991: 43). Through the use of descriptive techniques such as surveys of students’ attitudes toward CALL and observations of students’ behaviour during CALL work, it is possible to determine a number of “phenomena” relevant to CALL and second/foreign language learning.

Warschauer (1996) distinguishes three phases of CALL, illustrating the development of an increasing number of different ways in which the computer has been used in language learning and teaching:

1. Behaviouristic: The computer as tutor, serving mainly as a vehicle for delivering instructional materials to the learner. Ahmad et al. state that Behaviouristic CALL, conceived in the 1950s and implemented in the 1960s and 1970s, could be considered a sub-component of the broader field of computer-assisted instruction. Informed by the behaviourist learning model, this mode of CALL featured repetitive language drills, referred to as drill-and-practice (Ahmad, Corbett, Rogers & Sussex, 1985: 28).

2. Communicative: The computer is used for skill practice, but in a non-drill format and with a greater degree of student choice, control and interaction. This phase also includes (a) using the computer to stimulate discussion, writing or critical thinking, and (b) using the computer as a tool or workhorse - examples include word processors, spelling and grammar checkers, and concordances. Jones & Fortescue et al. mention that communicative CALL emerged in the late 1970s and early 1980s, at the same time that behaviourist approaches to language teaching were being rejected at both the theoretical and pedagogical level, and when new personal computers were creating greater possibilities for individual work. Proponents of communicative CALL stressed that computer-based activities should focus more on using forms than on the forms themselves, teach grammar implicitly rather than explicitly, allow and encourage students to generate original utterances rather than just manipulate prefabricated language, and use the target language predominantly or even exclusively (Jones & Fortescue, 1987; Philips, 1987; Underwood, 1984 also cited in Warschauer, M., & Healey, D., 1998).

3. Integrative: This phase is marked by the introduction of two important innovations: (a) multimedia, (b) the internet. The main advantage of multimedia packages is that they enable reading, writing, speaking and listening to be combined

in a single activity, with the learner exercising a high degree of control over the path that he/she follows through the learning materials. The internet builds on multimedia technology and in addition enables both asynchronous and synchronous communication between learners and teachers. The advent of the web has opened up a new range of tasks for MFL (Modern Foreign Languages) learners, e.g. web quests, web concordance, and collaborative writing. Kaplan (2002: 4) states that “in integrative approaches, students learn to use a variety of technological tools as an ongoing process of language learning and use, rather than visiting the computer laboratory on a once-a-week basis for isolated exercises (whether the exercises be behaviouristic or communicative)”.

We are now well into the third phase. The range of different types of CALL software currently available is impressive. As well as routine drill-and-practice programs, there are vocabulary games, action mazes, adventures and simulations, exploratory programs, and text reconstruction (total cloze) packages.

2.3. The Roles of Computers in Second / Foreign Language Learning

Education has traditionally been known as a conservative institution, one that responds slowly to change (Merrill et al., 1986). Therefore the idea of using computers for teaching purposes in subjects like modern languages arouses mixed feelings and meets with a variety of reactions (Kenning & Kenning, 1983). According to Vockell and Schwartz (1988), computer education parallels book education and the computer has the potential to have an impact on education as beneficial as that of the book. They explain the roles of computers by its strengths and weaknesses as:

“Strengths

- Computer can either control rate of presentation or leave it up to the learner - Computer can permit student to review previous information

- Computer can provide unique information or prompts as needed - Graphics can be realistic and interesting

- Graphics and sound can focus attention effectively - Audio and visual tracks employ different modalities - Computer can require interaction

- Computer can provide immediate feedback - Computer can record student performance Weaknesses

- More expensive than other media

- Unfamiliar to teachers and students” (Vockell and Schwartz, 1988: 73; also cited in Dağıstan, 1995 and Öz, 1995).

According to Philips (1986: 33), the computer is largely different from all other technological aids to language teaching with its potential of changing the teaching process. He thinks that the computer as a new technology promises to change the process of language teaching as he views the convergence of computers and communications as an order of magnitude more powerful than any teaching aids teachers have been accustomed to using.

Computers can be successful in increasing a variety of verbal and language skills, especially when they provide scaffolding, or assistance, to the learner (Shute & Miksad, 1997). In addition, CALL provides visual displays, animated graphics, sound, feedback, and individualization (Clement, 1994). By aiding these capabilities,

even drill-and-practice software can increase children’s language ability (Foster et al., 1994; Shapira, 1995).

Taylor (as cited in Levy, 1997) explains the roles of computers as a tutor, as a tool and as a tutee. While functioning as a tutor, computers provide the students with materials respond to the students’ questions and keep the records of each student. While functioning as a tool, the learner can benefit from computers in a variety of ways such as, improving skills like reading, writing, speaking, and searching subject areas. In explaining the function of the computer as a tutor, Taylor suggests that in order to use the software programs the learners and the teachers should learn how to use and program the computers.

Pennington (1996) addresses the attributes and potentials of the computer in education through language learning theory and the field of CALL. She suggests that the power of CALL is in helping to realize learning potentials as actualities. Specifically, she notes these attributes of computers as an ideal teacher or teaching system for language learning:

- “Helps learners develop and elaborate their increasingly specified cognitive representation for the second language

- Allows learners to experiment and take risks in a psychologically favourable and motivating environment

- Offers input to both conscious and unconscious learning processes

- Offers learners opportunities to practice and to receive feedback on performance

- Allows learners to learn according to their own purposes and goals - Put learners in touch with other learners

- Promotes cultural and social learning

- Promotes interactivity in learning and communication - Exposes the learner to appropriate contexts for learning - Expands the learner’s “zone of proximal development” - Builds learner independence” (Pennington, 1996:7).

Therefore the computer can be a uniquely effective medium for teaching along with the teacher. With these attributes, both the speed and efficiency of our mental efforts and intellectual development can be increased by computers (Jamieson-Proctor, 2002). Moreover, they appear to have established themselves as an inevitable part of modern human life. Sometimes even without any awareness people use them and take advantages of having them consciously and unconsciously, as in banking procedures, traffic controls, electronic vending machines, word processing, accounting, and record-keeping, office management, or even computer games. In fact, the faster they develop, the cheaper they become. In addition to the dramatic decrease of their prices in the last decade, they have become much more powerful, flexible and more adaptable. Hence, they have begun to be used more widely in very different disciplines. Education is perhaps one of the most important domains among these in which the use of computers has spread.

Although computers are incapable of interacting with their users with the sensitivity of a classroom teacher, it must be borne in mind that computer users can interact with computers with fruitful results in the right environment. What is more important is that language teachers can be freed by computers from some of the routine classroom tasks of teaching such as explanations, illustrations, and exercises which are traditionally dependent upon course and work books or tape recorders. Consequently, the language teacher, freed from such a routine work, will have more

time so that he can cope with the functions that the computer cannot achieve (Ingraham, 1990: 27-28; Öz, 1991: 289-290).

The role of computers in foreign/second language learning is best worded by Ahmad et al. (1985: 2):

“The computer is a servant. Its role in education is that of a medium. Far from threatening the teacher’s position, it is totally dependent on the teacher in many ways, for example, it is unable to create educational materials without a human to direct it. All the linguistic material and instructions for its presentation must be specified by the teacher. It is the teacher, then who can make the computer assume various roles.”

It is possible to assign these roles to the computer in a variety of physical settings. The teacher can situate the computer in the classroom or in a special computer laboratory. The computer can also be installed in a particular area of the library, or some other appropriate place where the language learner or a small group of them can use CALL lessons, exercises, or other activities without being disturbed and interrupted. Since most families have started buying computers for home use, the computer can also play its roles in the student’s home.

2.3.1. Motivation

The desire for something is simply motivation, which shows that if the learners are motivated they can achieve that goal rather easily. So motivation is very important in teaching and learning. The techniques which are used in computers are usually high motivated. The techniques and programs give answer to the learners’ interests and wishes. “Computer serves a colourful, different and interesting phantom that this phantom motivates the learner, too” (Alkan, 1997: 56).

Motivation is a critical factor when dealing with students who are learning how to write in English (DerMovsesian, 2001). For example, Warschauer (1996) found that computer-assisted instruction increases ESL/EFL students’ motivation in the writing classroom. Egbert et al. (1999: 6) argue that language learners “must be motivated to take the opportunities presented to them and to be cognitively engaged as they perform them.” Similarly, Wheeler et al. (2002) propose that motivation is a key factor for stimulating creative performance. Torrance (1972) also mentioned motivation as one of the factors for successful creative training in CALL.

By the computer, the learner’s incorrect response is immediately corrected and another chance is given to the learner till s/he finds and understands the correct one. Seeing the result of his/her study encourages the learner to learn (Huh, 2005). The lessons’ goals must be united with the learners’ goals. Without motivation there will be an absence of learning, on the other hand, teaching/learning process via computers encounters motivation in itself.

2.4. The Roles of Teacher in CALL Lessons

It might seem both interesting and difficult to start teaching in a computer lab for teachers who are used to teaching in the classroom without any computers. Opp-Beckman (1999) defines the necessary things for teachers who are planning to start teaching in a computer lab. These are: determining students’ expectations, which should be related to students’ cultural and technological experiences and trying to find support for students’ access to computers. She also suggests that teachers should be realistic and careful while integrating CALL into the curriculum. Following Huss and Susan (1990), it is important to choose the software programs that enable students to think search and understand the concepts on their own.

The roles of teacher in CALL instruction can be listed as choosing the right CALL programs to be integrated into curriculum, monitoring and guiding students, and solving software problems. The importance of CALL in allowing learners and teachers to recognize grammatical, semantic, and sociolinguistic aspects of language use cannot be separated from one another in language learning activity (Pennington, as cited in Garrett, 1990).

The CALL teacher needs to know about the computers’ internal workings. It shouldn’t be forgotten that the computer is a tool which does what it is told, in a very fast way, but also in a literal-minded way. Unlike human beings, there is no expression of feelings, of humour (Kenning & Kenning, 1983). After having a necessary hardware, teachers / educators should look for ways of using appropriate software in their classes. The level of human and financial investment (whether there are enough knowledgeable people to guide about the use of CALL, technological trends) should be considered as well (Gary, 1994; Locatis and Nuaim, 1999).

Often classrooms are teacher-centred while the computer laboratories are student-centred. This may also necessitate a change in the learning process and environment since the teacher must give up a degree of control over students and permit the class to become more student-centred rather than being teacher-centred (Neu and Scarcella, as cited in Dunkel, 1991). In a computer laboratory teachers are like a guide or a facilitator. Moreover they may be seen as a technician who solves technical problems related to passwords, printing and software. On the other hand more traditional classrooms the teachers are experts and directors rather than facilitators. Neu and Scarcella (1991) give an example of the changing role of a teacher in a computer writing class. They state that “in the computer-based writing class, the role of the teacher needs to change from that of ‘provider and judge’ to that of ‘facilitator and resource person’. This change in roles appears to meet the instruction of needs of adult learners”. Thus, individual guidance and consulting by

teachers might be more beneficial for learners since student must figure out the grammatical rules without initial whole class instruction. They also suggest that educators should not give the whole picture but make their students guess the parts that are not given. While studying on their own, students can make progress in being autonomous learners. (Neu and Scarcella, 1991: 173)

Sarı, indicates the roles of teachers in CALL as in the following statements: “1. The teacher must prepare ways for group affection.

2. The teacher must prepare activities for the evaluation of the learning period. 3. The teacher must give the learners learning responsibility as an advisor. 4. As an advisor, the teacher must give feedback.

5. The teacher must ask questions and give clues to improve learning. 6. The learners must be educated depending on real life situations.

7. The lessons must be student-centred and the teacher must help the learners less than the usual lessons.

8. The wanted and needed knowledge must be used, but not the unnecessary knowledge” (Sarı, 1993: 51).

CALL teachers should successfully get linguistic material into computers and instruct computers how to present the material to students. It is also helpful to keep track of students’ performance during CALL lessons. If necessary this information and these instructions can be changed by the teacher or the programmer. The teacher’s job in a computer lab should not be limited to a final report which shows the evaluation of students. Teacher must always be with the students in order to

guide them anytime they need. Feedback given during students’ progress is very useful (Chao, 1999).

Teachers must always try to know about the latest developments in educational technology. Knowing what works and why it works for students is also very important. One very significant and necessary thing is the teacher’s awareness of computer use for teaching. If teachers know that there is some software that helps teaching (and learning) they can attempt to use and benefit from it by examining and reviewing them carefully (Tuzcuoğlu, 2000). The software program that is being used or that is planned to be used should answer the teacher’s questions about the role of software in the curriculum. For the use of computers and software, there should be a scope and sequence that aim to develop student skills systematically, moving from simpler to complex.

When teachers are in the lab, they are regarded differently than they are regarded in a classroom. In a computer lab the teacher’s authority in terms of the learning environment loose its control over students. This permits the class to change from being teacher-centred to being student-centred. In the classroom, if students leave their seats and talk to each other, it is distracting and even disruptive, as these behaviours make difficulties for other students to hear and understand the teacher. This might disrupt the teacher as well. But in the lab, students do not have to pay attention to the teacher every moment; they work individually (Dunkel, 1991; Schofield, 1995). So in the lab teachers can be more tolerant of behaviours such as walking around and talking to peers in order to ask about work or make suggestions to each other. This kind of collaboration doesn’t disturb anyone in the computer lab. So, when compared to the classroom, the computer lab gives more freedom to be active (speaking, going near their friends) as the atmosphere is different, not like the classroom environment. Besides, the teacher can go from group to group sorting out problems, encouraging learners to speak in the target language and giving them the

individual attention which is often difficult to find time in a traditional classroom teaching environment.

Alkan (1997: 61) states that: “There are kinds of knowledge in the memory of the computer, but the learners need an advisor. Of course, this needed advisor is the teacher. No education can be done without teachers. Technology cannot take the place of the teachers but it can change the roles of the teachers”. Also Howie (1998) states that computers can not serve as a substitute for a teacher or a curriculum. There are a number of research studies that support this idea (Brierley & Kemble, 1991; Dhaif, 1989; Kenning & Kenning, 1983; Levy, 1997; Maddison &Maddison, 1987; Robinson, 1991). As Robinson (1991) notes, CALL should be considered an integral part of instruction and teachers as an integral part of CALL. Since computers cannot guide the students directly and cannot take the role of a teacher as a class manager, computers can be considered a complement to what teachers do in classrooms. Computers will not take over the teacher’s role. Teachers will continue to develop real life communication which the computer cannot provide (Galavis, 1998).

If educators are aware of what CALL brings to the learning and teaching process, and of its power to urge the teaching profession to better analyze what happens in classrooms and to reassess the main principles of the educational process, they can benefit from this technology and adapt it into their curricula (Kenning & Kenning, 1983).