T. C.

SELÇUK ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ

YABANCI DİLLER EĞİTİMİ ANA BİLİM DALI İNGİLİZCE ÖĞRETMENLİĞİ BİLİM DALI

COMPARISON OF TEACHER-PROVIDED KEYWORD

AND CONTEXT METHODS ON RETENTION OF

VOCABULARY

YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ

DANIŞMAN

Yrd.Doç.Dr. Abdülkadir ÇAKIR

HAZIRLAYAN Hakan YILMAZ

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my supervisor Assist. Prof.Dr. Abdülkadir ÇAKIR for his kind and constructive comments, suggestions, supervising throughout my study.

I would also like to express my gratitude to my first year students at Selcuk University Kadınhanı Vocational Collage, Computer Technologies and Programming Department for their contributions in this study as subjects.

Finally I wish to express my gratitude and apologies to my wife Huriye and my daughters Beyzagül and Zeynep for enduring much of my time and energy that should have been devoted to them was focused on this study instead.

Hakan YILMAZ Konya-2007

ÖZET

Bu çalışmanın amacı, kelimelerin akılda kalıcılığı bakımından, öğretmen tarafından sağlanmış anahtar kelime metoduyla, bağlamsal metodun etkisini karşılaştırmaktır. Selçuk Üniversitesi, Kadınhanı Meslek Yüksekokulu, Bilgisayar Teknolojisi ve Programlama Bölümünden, İngilizcesi başlangıç düzeyinde olan 84 öğrenci deneylere katılmıştır. Öğrenciler deney ve kontrol grupların oluşturmak için iki gruba ayrılmıştır. Çalışmada kullanılmak üzere 20 sözcük seçilmiştir. Yeni sözcüklerin sunumundan önce öğrencilere ön test uygulanmıştır. Kelimeler deney grubuna anahtar kelime metoduyla, kontrol grubuna ise bağlamsal metot kullanılarak öğretilmiştir. Yakın hatırlama ve tanıma testleri her iki gruba da uygulamadan hemen sonra verilmiştir. Uzun dönem hatırlamayı ölçmek için uzak hatırlama ve tanıma testleri, yakın testlerden beş hafta sonra yapılmıştır. Öğretmen tarafından sağlanmış anahtar kelime metodu ile bağlamsal metot arasındaki farkın analizi için t-test hesaplamaları, ön, yakın ve uzak testlerin sonuçlarında kullanılmıştır. Sonuç olarak, kelimelerin yakın ve uzak hatırlanması ve tanınmasında, öğretmen tarafından sağlanan anahtar kelime metodunun, bağlamsal metottan daha etkili olduğu saptanmıştır.

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study is to investigate the comparison of the effects of the teacher–provided keyword method and context method on retention of the vocabulary items. 84 students who were at the elementary level of English from Selcuk University, Kadınhanı Vocational School, Computer Technology and Programming Department took part in the experiments. The students were divided into two groups to form the experimental and the control groups. 20 target vocabulary items were used in the study. Each group was given a pre-test before the presentation of the new words. The vocabulary items were taught with the keyword method to the experimental group, and the control group was introduced with the context method. Immediate recall and recognition tests were applied to each group after the treatment. To measure long term retention, delayed recall and recognition tests were given to the groups five weeks after the immediate tests. To analyse the difference between the teacher–provided keyword method and context method, t-test calculations were used with the results of the pre-tests, immediate and delayed tests. According to the results, the teacher-provided keyword method is more effective than the context method in immediate and delayed recall and recognition of the vocabulary.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER I ... 1

INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1. Background to the Study ... 1

1.2. The Purpose of the Study ... 4

1.3. Significance of the Study... 4

1.4. Research Questions ... 5

1.5. Limitations... 5

CHAPTER II ... 7

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ... 7

2.1. Background of Vocabulary Teaching... 7

2.2. What is vocabulary? ... 9

2.3. Knowing a word ... 11

2.4. Active and Passive Vocabulary ... 12

2.5. Memory ... 13

2.5.1. Short and Long Term Memories ... 15

2.5.2. Remembering the New Words ... 16

2.6. Memory Strategies... 17

2.6.1. Creating Mental Linkages ... 18

2.6.1.1. Grouping... 18

2.6.1.2. Associating/Elaborating... 18

2.6.1.3. Placing New Words into a Context ... 19

2.6.2. Applying Images and Sounds... 19

2.6.2.1. Using Imagery ... 19

2.6.2.2. Semantic Mapping... 19

2.6.2.3. Using Keywords ... 19

2.6.2.4. Representing Sounds in Memory ... 20

2.6.3. Reviewing Well ... 20

2.6.3.1. Structured Reviewing ... 20

2.6.4. Employing Action ... 20

2.6.4.1. Using Physical Response or Sensation... 21

2.7. Mnemonics ... 21

2.7.1. Loci Method ... 22

2.7.2. The Pegword Method ... 22

2.7.3. Letter Strategies... 23

2.7.4. Keyword Method... 24

2.8. Context Method ... 26

2.9. Studies on Keyword Method ... 28

CHAPTER III ... 35 METHODOLOGY ... 35 3.1. Introduction ... 35 3.2. Research Design ... 35 3.3. Subjects ... 36 3.4. Materials ... 37 3.4.1. Instructional Material ... 37 3.4.2. Testing Material... 37

3.5. Presentation of the Method... 38

3.6. Data Analysis Procedures... 40

CHAPTER IV ... 41

RESULTS... 41

4.1. Results of the Study... 41

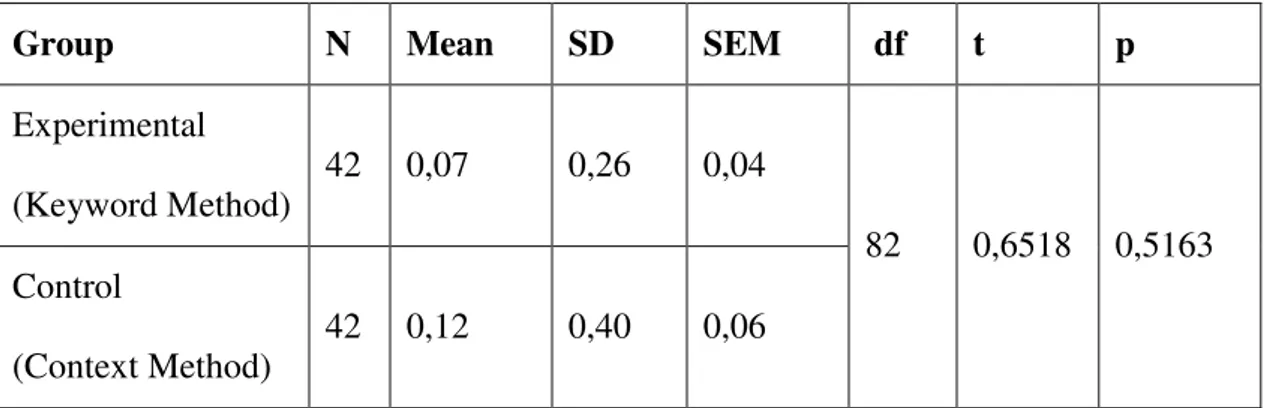

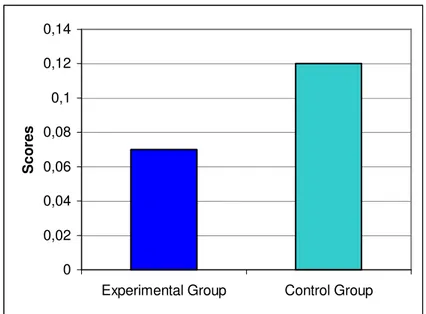

4.2.1. Pre-test Results for Recall ... 41

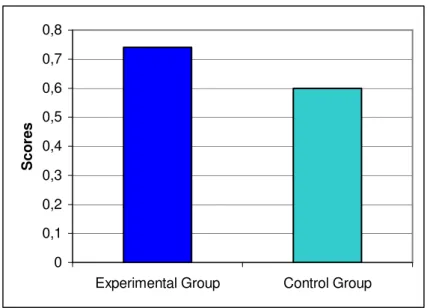

4.2.2. Pre-test Results for Recognition ... 42

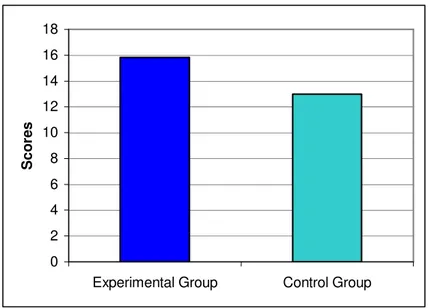

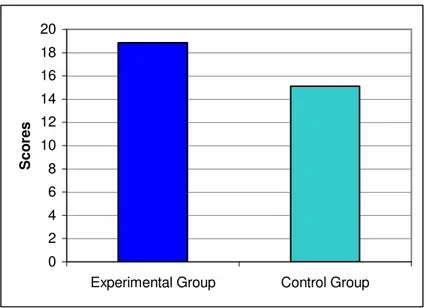

4.2.3. Immediate Test Results for Recall... 43

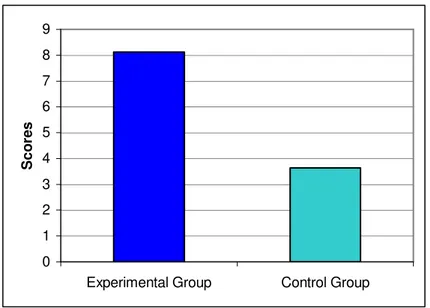

4.2.4. Immediate Test Results for Recognition ... 44

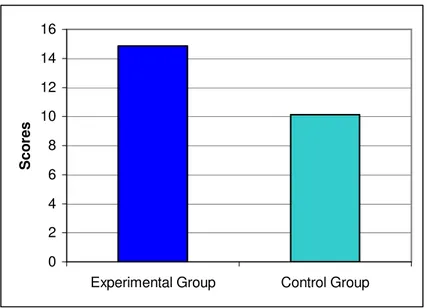

4.2.5. Delayed Test Results for Recall ... 45

4.2.6. Delayed Test Results for Recognition ... 46

CONCLUSION ... 48

APPENDICES... 50

APPENDIX A ... 50

APPENDIX B... 51

APPENDIX D ... 56 APPENDIX E ... 57 APPENDIX F ... 59 APPENDIX G ... 60 APPENDIX H ... 62 APPENDIX I ... 63 APPENDIX J... 65 APPENDIX K ... 66 APPENDIX L... 67 APPENDIX M... 68 REFERENCES ... 69

LIST OF TABLES

Table 4.1: Pre-test Results for Recall ... 41

Table 4.2: Pre-test Results for Recognition... 42

Table 4.3: Immediate Recall Test Results ... 43

Table 4.4: Immediate Recognition Test Results... 44

Table 4.5: Delayed Recall Test Results... 45

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 4.1: Comparison of the Vocabulary Recall Pre-test Results ... 42 Figure 4.2: Comparison of the Vocabulary Recognition Pre-test Results... 43 Figure 4.3: Comparison of the Immediate Vocabulary Recall Test Results ... 44 Figure 4.4: Comparison of the Immediate Vocabulary Recognition Test results . 45 Figure 4.5: Comparison of the Delayed Vocabulary Recall Test Results ... 46 Figure 4.6: Comparison of the Delayed Vocabulary Recognition Test Results.... 47

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background to the Study

The importance of learning vocabulary in foreign language teaching can’t be neglected at present. Although less importance was given to vocabulary learning in the past, many experienced teachers of English as a second language have realised that knowing a language means knowing its vocabulary as well.

What to teach and how to teach new words are very important issues in vocabulary teaching. Deciding how to present the new vocabulary items to students is very important during the teaching process. The new vocabulary items should be presented in such a way that the students can learn and remember them easily when they are needed.

The seek of presenting new vocabulary items in the most effective way forced teachers to use various methods, approaches and techniques. According to Allen (1983:5) there is more attention to techniques for teaching vocabulary today. One reason is in many ESL classes even where teachers have devoted much time to vocabulary teaching, the results have been disappointing. Allen (1983:5) also states that scholars today are taking a new interest in the study of word meanings. A number of research studies have recently dealt with lexical problems (problems related to words) because lexical problems frequently interfere with communication, and communication fails when speaker doesn’t use the right words.

Teachers have known the importance of vocabulary teaching. They closely observe how students of foreign language face difficulties when they don’t know the necessary words while they are speaking. The teachers of second language still have the problems about vocabulary teaching as Allen (1983:6) summarizes the questions below:

Which English words do students need most to learn? How can we make those words seem important to students? How can so many needed words be taught during the short time our students have for English?

What can we do when a few members of the class already know words that the others need to learn?

Which aids to vocabulary teaching are available?

How can we encourage students to take more responsibility for their own vocabulary learning?

What are some good ways to find out how much vocabulary the students have actually learned?

There are many ways to teach vocabulary and some of the linguists have made classification of strategies of vocabulary teaching. Gairns and Redman (1986:73-83) listed traditional approaches and techniques used in the presentation of new vocabulary items as follows:

Visual techniques Visuals

Mime and gesture Verbal Techniques

Use of illustrative situations (oral and written) Use of synonymy and definition

Contrasts and opposites Scales

Examples of the type Translation

Student -Centred Learning Asking others

Using dictionary Contextual guesswork

Oxford (1990;18) cited in Karaaslan (1996;27) has developed a system for categorizing the Direct and Indirect language learning strategies as follows:

Direct Strategies: Memory, Cognitive and Compensational Strategies

I. Memory Strategies

A. Creating mental linkage

1. Grouping

2. Associating / elaborating

3. Placing new words into a context

B. Applying images and sounds

1. Using imaginary

2. Semantic mapping

3. Using Keywords

4. Representing sounds in memory

C. Reviewing well

1. Structured reviewing

D. Employing acting

2. Using Mechanical techniques II. Cognitive strategies

A. Practicing

1. Repeating

2. Formally practicing with sounds and writing

3. Recognizing and using formulas and patterns

4. Recombining

5. Practicing Naturalistically

B. Receiving and sending messages

1. Getting the idea quickly

2. Using resources for receiving and sending

C. Analyzing and reasoning

1. Reasoning deductively

2. Analyzing expressions

3. Analyzing contrastively

4. Translating

5. Transferring

D. Creating structure for input and output

1. Taking notes

2. Summarizing

3. Highlighting

III. Comprehension strategies A. Guessing Intelligently

1. Using linguistic clues

2. Using other clues

B. Overcoming limitations in speaking and writing

1. Switching to the mother tongue

2. Getting help

3. Using mime or gesture

4. Avoiding communication partially or totally

5. Selecting the topic

6. Adjusting or approximating the message

7. Coining words

8. Using a circumlocution or synonym

Among the strategies here, memory strategies where keyword method takes part is our main interest in this study. Memory strategies are also called mnemonics. The word mnemonics means aiding the memory. Highbee cited in Külekçi (2000:3) states that mnemonics is a system or technique which aids the memory by means of stories, rhymes acronyms, verbal mediators and visual imagery.

According to Oxford cited in Külekçi (2000:2), though some teachers think vocabulary learning is easy, language learners have a serious problem remembering the large amounts of vocabulary necessary to achieve fluency in speaking. Language learning strategies such as grouping associating/elaborating, placing new words into a

context, using imagery, semantic mapping, using keywords, representing sounds in memory and structured reviewing are used for better vocabulary learning.

The keyword method was introduced by Atkinson (1975:821) for learning foreign vocabulary. The keyword method is a mnemonic device which helps the learner to transform or organize material in order to enhance its retrievability. The method includes two steps. First, acoustic similarity of the English word is found in first language which is called keyword and in the second step a visual image is created in learners mind including keyword and equivalent of the English word.

For example to learn the English word “cradle”, the Turkish word “kredili” which has acoustic similarity is chosen as a keyword. The meaning of “cradle ” “beşik” in Turkish and the keyword “kredili” are used to create a pictorial image including a shop and a sign “Kredili beşik satışı vardır” on a cradle on the shop window in students minds. This pictorial image triggers students’ memory to remember the word “cradle”

1.2. The Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this experimental study is to see which of the two methods, teacher-provided keyword method and context method, is more effective in helping students’ recognition and retention of vocabulary in short and long term memory. In this way students will be able to learn the required words in a short time, and minimum lack of retention and recognition will be obtained. The results of the immediate and delayed tests which were given after the presentation of the selected vocabulary items will help us to examine students’ retention and recognition. This study was conducted in a Vocational Collage of Turkish University classroom setting.

1.3. Significance of the Study

All of the second language teachers have been asked the questions “How can I learn the new words easily and How can the new words be kept in mind?” by the students. As a second language teacher I have faced these kinds of questions several times. I worked at various schools from secondary to university or I had classes with different ages from 10 to 40, and I observed that keeping the new vocabulary in mind for long term is an important problem. Teachers of second language have presented new

vocabulary items during lessons and at this stage there is no problem. What are waiting for us in the later steps includes difficulties in remembering the words which we taught in previous lessons and related with this problem there are difficulties in producing sentences and lack of communication. Same problems have been spoken by other teachers of English at language schools or preparation classes.

The importance of the acquisition of vocabulary cannot be neglected in learning a second language. Since the time is limited at schools, vocabulary items must be given to the students as in an effective and practical way as possible. In this case, memory strategies may help students to learn and remember words in learning foreign language. By using keyword method and generating their own keywords for different vocabulary items, students can increase their abilities on vocabulary learning. It is important for teachers of foreign language to learn if the teacher-provided keyword method can help them.

1.4. Research Questions

In this study the answers of the questions below will investigated:

1- Is the teacher-provided keyword method superior to the context method in immediate recall of vocabulary?

2- Is the teacher-provided keyword method superior to the context method in delayed recall of vocabulary?

3- Is the teacher-provided keyword method superior to the context method in immediate recognition of vocabulary?

4- Is the teacher-provided keyword method superior to the context method in delayed recognition?

1.5. Limitations

This study focuses on only the retention and recognition of the vocabulary. The study was carried out with the first year students at Selcuk University, Kadınhanı Vocational School, Computer Technology and Programming Department who were at elementary level. The study was applied on only one level of learners. Students of other

levels like pre-intermediate, intermediate, and upper intermediate couldn’t be found at that school. The students had only four hours lesson of English and their level is not very high for context method because some of the students faced difficulties guessing the meaning from the texts, at that time teacher helped them to understand by creating simpler context. The experimenter of the study couldn’t find more efficient students at that school because he has worked there as an English teacher, on the other hand it is difficult to go other faculties or the School of Foreign Languages due to the administrative conditions.

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 2.1. Background of Vocabulary Teaching

Nunan (1998:116) states that the position of vocabulary within the curriculum has varied considerably over the years. It suffered significant neglect during the 1950’s when audio- lingual method had a dominant influence on methodology. But in 1970’s it regained its importance under the influence of communicative language teaching.

In the 20th century, the main emphasis of language teaching has been on the grammar. Nunan (1998:117) argues that “While grammar translation approaches to the teaching of language provided a balanced diet of grammar and vocabulary, audio-lingualists suggested that the emphasis should be strongly on the acquisition of the basic grammatical patterns of the language.” Audio-lingualists believed that at first, basic patterns of language must be learnt and then large vocabulary store could be built on it.

According to Seal in Celce and Murcia (1991:296), in the early decades of the 20th century, in fact, vocabulary teaching and research were absolutely respectable. Grammar Translation Method and Reading Approach were the leading language teaching methodologies. Both of these approaches involved a great deal of direct vocabulary teaching and learning. In the same period, EFL lexicography developed, and much research were undertaken to establish which words were the most useful to be taught at different stages in the learning process.

Seal in Celce and Murcia (1991:297) also claims that the emergence of the Audio Lingual Method had an immediate and devastating effect on further development in vocabulary teaching and research. In terms of this method vocabulary learning should be kept to a minimum.

Allen (1983:1) argues that vocabulary has been neglected in programs for teachers during much of the twentieth century. One reason why vocabulary was neglected in teacher-preparation programs during the period between 1940-1970 was that it had been emphasized too much in language classrooms during the years before that time. There was a false belief that learners could master the language by learning a certain number of English words, along with the meanings of those words in their own language. Allen (1983:2) states that some specialists in methodology seemed to believe

that the meaning of words could not be adequately taught, so it was better not to try to teach them. In the 1950’s many people began to notice that vocabulary teaching is not a simple matter.

Allen (1983:2) mentions that in some books and articles about language teaching, writers gave the impression that it was better not to teach vocabulary at all because scholars, who prepared teachers, gave the impression that vocabulary learning was so complex that one might better devote most of the class time to teach the grammatical structures, with just a few vocabulary items, since students were not to believed to give the full and accurate understanding of the meanings of the words in class. Allen summarizes the reasons as follows:

1-Many who prepared teachers felt that grammar should be emphasized more than vocabulary, because vocabulary was already being given too much time in long class.

2- Specialists in methodology feared that students would make mistakes in sentence construction if too many words were learned before the basic grammar had been mastered. Consequently, teachers were let to believe it was best not to teach much vocabulary.

3- Some who gave advice to teachers seemed to be saying that word meanings can be learned only through experience, that they cannot be adequately taught in a class. As a result, little attention was directed to techniques for vocabulary teaching.

(Allen, 1983:3)

By the 1970’s Audio Lingual Method had fallen disrepute, nevertheless, the concept that vocabulary learning was some how of secondary importance in second language pedagogy had not passed with it. It was during this period that several voices could be heard challenging the current situation (Seal in Celce & Murcia (1991:297) cited in Roser-Sweig 1979; Judd, 1978; Marea,1981;Richards 1976).

During 1980’s there was a revival of interest and activity in lexical subjects. Seal states that:

One can point as indirect evidence to several significant publishing events. There has been the publication of several innovative lexical reference works: the Longman Lexicon (Mc Arthur, 1981), which

lists items according to their semantic fields; the BBI Combinatory Dictionary (Benson, Benson & Ilson, 1986), which lists items together with their most frequent collocates; and the Collins COBUILD Dictionary (Sinclair, 1987), which uses as its citation source a computer corpus of 7.3 million running words. A number of handbooks for teachers devoted entirely to the teaching of vocabulary have been published (Allen, 1983; Gairns & Redman; 1986; Morgan & Rinvolucri, 1986; Wallace, 1982). Some theory-based vocabulary textbooks for ESL students have come onto the market (Rudzka, Channell, Ostyn, & Putseys, 1981,1985; Seal, 1987, 1988) An anthology of vocabulary-based research has been published (Carter & McCarthy, 1988). By contrast with other areas in language learning such a record in publishing may not seem overly impressive; however, in contrast with the amount of attention given to vocabulary over the previous two decades such activity may be considered a veritable flood.

(Seal cited in Celce and Murcia, 1991:297)

Seal explains three developments in the theory and practice of language teaching as the reason of a reassessment of the role that vocabulary can play in second language learning has occurred at this time as follows:

First, the notion that second language learners develop their own internal grammar in predetermined stages that cannot be disturbed by grammar instruction has led some to propose that the traditional teaching of structure should be de-emphasized. At the same time, there has been a shift toward communicative methodologies that emphasize the use of language rather than the formal study of it. These two forces together have led to a view of language teaching as empowering students to communicate, and clearly, one effective way to increase students' facility in communicating is to increase their vocabularies. Finally, within the domain of teaching English for Academic Purposes (EAP), teachers have become increasingly aware that non-native students are significantly disadvantaged in their academic studies on account of the small size of their second language vocabularies. Thus, the de-emphasis on grammar, the newly placed emphasis on communication, and the perceived needs of EAP students have had the effect of elevating the importance of vocabulary in recent years.

(Seal cited in Celce and Murcia, 1991:297-298)

2.2. What is vocabulary?

This question can be easily answered by saying only “words” but, the answer can cover many things like “auxiliaries, verbs, nouns, adjectives, idioms, multiword verbs,

etc.” Ur answers this question as below and at the end he prefers using “vocabulary items” instead of “words”.

Vocabulary can be defined roughly as the words we teach in the foreign language. However, a new item of vocabulary may be more than a single word: for example “post office” and” mother- in- law”, which are made up of two or three words but express a single idea. There are also multiword idioms such as “call it a day” where the meaning of the phrase cannot be deduced from an analysis of the component words. A useful convention is to cover all such cases by talking about “vocabulary items” rather than “words”.

(Ur, 1996:60)

The importance of vocabulary learning was emphasised by many linguists. For example, According to Wallece (1988:9) “there is a sense in which learning a foreign language is basically a matter of learning its vocabulary.” For Read (2001:1) “words are the basic building blocks of language, the units of meaning from which larger structures like sentences, paragraphs and whole texts are formed.” Rivers cited in Nunan (1998:117) also argues that “the acquisition of an adequate vocabulary is essential for successful second language we the structures and functions we may have learned for comprehensible communication.” Nunan (1998:118) states that “The consensus of opinion seems to be that the development of a rich vocabulary is an important element in the acquisition of a second language.” According to Harmer (1991:153) vocabulary is like the vital organs and the flesh of the body whereas structures are the skeleton. Scrivener (1994:73) also states that “Vocabulary is a powerful carrier of meaning. Beginners often manage to communicate in English by using the accumulative effect of individual words”. He defends his idea by giving the example below:

“A student who says ‘Yesterday, Go disco, and friends, dancing’ will almost certainly get much of his message over despite completely avoiding grammar - the meaning is conveyed by the vocabulary alone. A good knowledge of grammar, on the other hand, is not such a powerful tool. I wonder if you could lend me your . . . means little without a word to fill the gap, whereas the gapped word - calculator- on its own could possibly communicate the desired message: Calculator?”

Wallace (1988:9) claims that “learning a foreign language is basically a matter of learning the vocabulary of that language. Not being able to find the word you need to express yourself is the most frustrating experience in speaking another language.

However, the importance of vocabulary teaching mustn’t be understood that we may neglect the grammar. Harmer (1993:154) suggests that “The acquisition of vocabulary is just as important as the acquisition of grammar -though the two are obviously interdependent- and teachers should have the same kind of expertise in the teaching of vocabulary as they do in the teaching of structure.”

The degree of proficiency in a language is related with the words you know. The more words you know, the better you can express your ideas and communicate with others. Without words, people can’t use the words effectively.

2.3. Knowing a word

In simple terms, knowing a word means recognizing it and understanding its meaning in a spoken or written text. Knowing a word can’t be defined by learning only the meaning of it. Knowing a word is more than its dictionary definition. Vocabulary learning also includes the ability to recall the learnt word when needed, use it in correct form, pronounce it properly, spell it correctly, use it with the words it usually goes with (collocates), and be aware of and use it in all its connotations and associations. Wallace defines knowing a word:

To know a word in target language as well as the native speaker knows it may mean the ability to:

a) recognize it in its spoken or written form;

b) recall it at will;

c) relate it to an appropriate object or concept;

d) use it in the appropriate grammatical form;

e) pronounce it in a recognizable way in speech;

f) spell it correctly in writing;

g) use it with the words it correctly goes with, in the correct

collocation;

h) use it at the appropriate level of formality;

i) be aware of its connotations and associations

(Wallace, 1982:27)

Harmer (1991;158) suggest that, in order to know a vocabulary item, we must be aware of its meaning, use, formation and grammar. Harmer cited in Koç and Bamber (1997:6.2) explains them as follows:

Meaning: For the word book Harmer cites 14 dictionary

meanings.

Use: A word may carry information about style. Good morning

and Hi indicate different levels of formality. A word may also indicate register. Doctors will choose different words to talk to colleagues and patients- A word's meaning can also be extended in metaphor and idiom.

Formation: Words change shape according to the affixes

attached to them, and also according to their function. To illustrate this point, Harmer draws our attention to the relationship between death,

dead, dying and die despite their differences in form.

Grammar: Nouns may be countable, for example

chair/chairs, uncountable, for example furniture, or fixed forms such

as the news.

Ur makes a similar list about what needs to be taught to language learners:

1. Form: pronunciation and spelling 2. Grammar

3. Collocation

4. Aspects of meaning (1): denotation, connotation,

appropriateness

5. Aspects of meaning (2): meaning relationships ( Synonyms, Antonyms, Co-hyponyms or co-ordinates, Super-ordinates, Translation)

6. Word formation

(Ur, 1996:61-62)

2.4. Active and Passive Vocabulary

In our daily life we use certain amount of words to communicate. The amount of words we use depends on our education. Although we know many words we needn’t use all of them. We can express our needs by simple words. There is a distinction often made between active and passive vocabulary. The terms are also used as “productive” and “receptive” vocabulary. Gains and Redman define the terms:

“We understand ‘receptive’ vocabulary to mean language items which can only be recognised and comprehended in the context of reading and listening material, and ‘productive’ vocabulary to be language items

which the learner can recall and use appropriately in speech and in writing.”

(Gains and Redman,1998:64)

Harmer (1991:159) prefers using the terms ‘active’ and ‘passive’ vocabulary. He defines that ‘active vocabulary’ are the words that the learner can understand, pronounce correctly and use in speech and writing, and ‘passive vocabulary’ are the words that can only be recognized and understood in the context of reading and listening material, but cannot be produced correctly by the student.

Gairns and Redman (1998:65) state that “an educated native is able to ‘understand’ between 45000 and 60000 items, although no native speaker would pretend that his productive vocabulary would approach this figure.”

The teacher’s role in this situation is to select the commonly used words and teach them. Textbooks which have designed at different levels and have commonly used words in daily life can help teachers about solving this problem because in those kinds of books, classification has already been made by the writers. Another useful application is to use the words which cover more than one meaning. For example, Harmer (1991:156) gives 14 meanings of the word “book”.

The active vocabulary and passive vocabulary can easily be change its place to passive aren’t practiced. As Harmer states:

We can assume that students have a store of words but it would be difficult to say which are active and which are passive. A word that that has been ‘active’ through constant use may slip back into the passive store if it is not used. A word that students have in their passive store may suddenly become active if the situation or context provokes its use. In other words the states of a vocabulary item does not seem to be a permanent state of affairs.

(Harmer, 1991:159)

2.5. Memory

The teachers of a foreign language have faced the problem of learners’ forgetting the vocabulary items which were taught in previous lessons. In teaching a foreign language, helping students to remember words or helping them to store words in memory is a very important task. Gairns and Redman (1986:86) claims that

understanding how information in the memory is stored and why some of the information is recorded in mind and some is flown away is important for language teachers to help students learning words. This information is useful for language teachers in order to teach vocabulary effectively and for the retention of new language items. Scrievener (1994:73) states that “There is no point in studying new words if they are not remembered.”

Our mental lexicon is highly organised and efficient. However, storage of the information is neither haphazard nor like a dictionary. Brown and Mc Neil cited in Gairns and Redman gives us clues about lexical organisations after some experiment:

The experimenters gave testees definitions of low frequency vocabulary items and asked them to name the item. One definition was, 'A navigational instrument used in measuring angular distances, especially the altitude of the sun, moon and stars at sea.’ Some testees were able to supply the correct answer (which was 'sextant'), but the researchers were more interested in the testees who had the answer 'on the tip of their tongues'. Some gave the answer 'compass’ , which seemed to indicate that they had accessed the right semantic field but found the wrong item. Others had a very clear idea of the 'shape' of the item, and were often able to say how many syllables it had, what the first letter was, etc.

(Brown and Mc Neil cited in Gairns and Redman, 1986:88) These experiments prove that lexical systems are interrelated; at a very basic level, there appears to be a phonological system, a system of meaning relations and a spelling system.

Freedman and Loftus cited in Gairns and Redman (1986:88) investigate how the mental lexicon is organised is by comparing the speed at which people are able to recall items. In this experiment:

Freedman and Loftus (1971) asked testees to perform two different types of tasks:

e.g. 1 Name a fruit that begins with a p.

2 Name a word beginning with p that is a fruit.

Testees were able to answer the first type of question more quickly than the second. This seems to indicate that 'fruits beginning with p' are categorised under the 'fruit' heading rather than under a 'words beginning with p' heading. Furthermore, experimenters discovered in subsequent tests that once testees had access to the 'fruit' category, they were able to find other fruits more quickly.

This experiment proves that semantically related items are stored together.

Forster cited in Gairns and Redman (1986;89) put forward the theory that all items are organised in a large “master file” and that there are a variety of “peripheral Access files ” which contain information about spelling, phonology, syntax and meaning. Entries in the master file are also held to be cross-referenced in terms of meaning relatedness.

Word frequency is another factor that affects storage, as the most frequently items are easier to retrieve. We can use this information to attempt to facilitate the learning process by grouping items of vocabulary in semantic fields, such as topics.

2.5.1. Short and Long Term Memories

Gairns and Redman (1986:86) define that “The ability of holding information for a short time, like up to thirty seconds, is called short term memory.” Researchers claim that new items are firstly stored in the short term memory where retention is not very effective. This kind of memory requires fairly constant repetition and interrupting this repetition probably hinders the ability. In this type of memory, retention is not effective if the number of the chunks of information is more than seven. It is often experienced that after repeating words several times, students are able to recall them in a short time.

When we talk about memory, in fact we are talking about long term memory since our short term memory capacity is up to 30 seconds. According to Gairns and Redman (1986:87) “Long term memory is our mental capacity for retention of information can last minutes, weeks and years after the original input. This type of memory can store any amount of new information and it is inexhaustable.”

Long term memories are stored in a different place than short term memories and in a different way. Gairns and Redman (1986:87) state that in some cases, we can remember certain information either by means of repetition or with no conscious attempt to learn it. What’s more, there is no clear distinction between the short and long term memory. Some information entering short term memory may pass quite effortlessly into long term memory.

For long term memories to survive for a very long time for example decades, it is taught that we have recalled them from time to time, otherwise they will be erased as part of forgetting. In other words, when we remember something, we strengthen the connection of it even after many years.

2.5.2. Remembering the New Words

Although these organisational networks in the memory work effectively, students still forget some of the vocabulary learning language even we think that they are well learned.

According to Scrievener (1994:88-89) “Many students record newly learned words in long lists in their exercise books. The action of noting down the lists of words is no guarantee that remembering will take place. Remembering involves putting into storage, keeping in storage, retrieving and using.”

According to the decay theory explained by Gairns and Redman (1986:89), information kept in memory falls into disuse if it is not practiced and revised. On the other hand according to the Cue-Dependent Forgetting Theory memory failure is related with the lack of retrieval rather than storage.

Carter and Nunan (2001:42) mentions that a definition of learning a word depends crucially on what we mean by a word, but it also depends crucially on how a word is remembered, over what period of time, and in what circumstances it can be recalled and whether learning a word also means that it is always retained.

Nattinger in Roland and McCarty(1988:64) claims that words are stored and remembered in a network of associations and they can be of many types and be linked in a number of ways. In our mental lexicon words are tied to each other by meaning, form, sound, sight -we link similar shapes in our minds eye- and by others parts of the contexts in which we have learned or experienced them. He also emphasises the importance of form in vocabulary retention:

Form may be more important than meaning in remembering a vocabulary item. We rely on the form of a word to lead us to its meaning, for we see or hear a particular shape and try then to remember what that shape means. Therefore, in teaching comprehension, we need to teach strategies that take form as the principal path to meaning. For production

on the other hand, it is the meaning that guides us to appropriate form for particular situation.

(Nattinger in Roland and McCarty, 1988:64)

2.6. Memory Strategies

Learners of foreign language use various strategies for learning new vocabulary easily. ‘Learning strategy’ is defined in The Longman Dictionary of Applied Linguistics as:

I- (in language learning) a way in which a learner attempts to work outthe meanings and uses of words, grammatical rules and other aspects of language. For example, by use of ‘generalization’ and ‘inferencing’.

II-(in second language learning, studying, reading, etc.)intentional behaviour and thoughts that learners make use of during learning in order to better help them understand, learn or remember new information. These may include focusing on certain aspects of new information analyzing and organizing information during learning to increase comprehension, evaluating learning when it is completed to see if further action is needed. Learning strategies may be applied to simple tasks involving language comprehension and production. The effectiveness of second language learning is thought to be improved by teaching learners more effective learning strategies.

(Richards, 1985: 208-209)

Oxford defines learning strategies as specific actions, behaviours, steps, or techniques- such as seeking out conversation partners, or giving oneself encouragement to tackle a difficult language task- used by students to enhance their own learning.(URL 1)

Oxford cited in Karaaslan (1996:27) divides language learning strategies into two major types, direct and indirect. The list of the direct strategies was given in the first chapter of this study. The strategies used directly in dealing with a new language are called direct language learning strategies. The three groups which belong to the direct language learning strategies are memory, cognitive and compensation. In memory

strategies, ‘using keywords’ is the main interest of this study. Memory strategies are divided into four sub-titles:

Creating mental linkage: Grouping, Associating / elaborating, Placing new words

into a context

Applying images and sounds: Using imaginary, Semantic mapping, Using

Keywords, Representing sounds in memory

Reviewing well: Structured reviewing

Employing acting: Using physical response or sensation, Using Mechanical

techniques

Oxford cited in Külekçi ( 2000: 21-24) gives the definitions of memory strategies as follows:

2.6.1. Creating Mental Linkages 2.6.1.1. Grouping

Classifying or reclassifying language material into meaningful units, either mentally or in writing, to make the material easier to remember by reducing the number of discrete elements. Groups can be based on type of word (e.g., all nouns or verbs), topic (e.g., words about weather), practical function (e.g., terms for things that make a car work), linguistic function (e.g., apology, request, demand), similarity (e.g., warm, hot, tepid, tropical), dissimilarity or opposition (e.g., friendly/unfriendly), the way one feels about something (e.g., like, dislike), and so on. The power of this strategy may be enhanced by labelling the groups, using acronyms to remember the groups, or using different colours to represent different groups.

2.6.1.2. Associating/Elaborating

Relating new language information to concepts already in memory, or relating on piece of information to another, to create associations in memory. These associations can be simple or complex, mundane or strange, but they must be meaningful to the learner. Associations can be between two things, such as bread and butter, or they can be in the

form of a multipart "development", such as school-book-paper-tree-country-¬earth. They can also be part of a network, such as a semantic map.

2.6.1.3. Placing New Words into a Context

Placing a word or phrase in a meaningful sentence, conversation, or story in order to remember it. This strategy involves a form of associating/elaborating, in which the new information is linked with a context. This strategy is not the same as guessing intelligently, a set of compensation strategies which involve using all possible clues, including the context, to guess the meaning.

2.6.2. Applying Images and Sounds 2.6.2.1. Using Imagery

Relating new language information to concepts in memory by means of meaningful visual imagery, either in the mind or in an actual drawing. The image can be a picture of an object, a set of locations for remembering a sequence of words or expressions, or a mental representation of the letters of a word. This strategy can be used to remember abstract words by associating such words with a visual symbol or a picture of a concrete object.

2.6.2.2. Semantic Mapping

Making an arrangement of words into a picture, which has a key concept at the centre or at the top, and related words and concepts linked with the key concept by means of lines or arrows. This strategy involves meaningful imagery, grouping, and associations; it visually shows how certain groups of words relate to each other.

2.6.2.3. Using Keywords

Remembering a new word by using auditory and visual links. The first step is to identify a familiar word in one's own language that sounds like the new word - this is the "auditory link". The second step is to generate an image of some relationship between the new word and a familiar one - this is the "visual link". Both links must be meaningful

to the learner. For example, to learn the new French word potage (soup), the English speaker associates it with a pot and then pictures a pot full of potage. To use a keyword to remember something abstract, such as a name, associate it with a picture of something concrete that sounds like the new word. For example, Minnesota can be remembered by the image of a mini soda.

2.6.2.4. Representing Sounds in Memory

Remembering new language information according to its sound. This is a broad strategy that can use any number of techniques, all of which create a meaningful, sound based association between the new material and already known material. For instance, you can (a) link a target language word with any other word (in any language) that sounds like the target language word, such as Russian brat (brother) and English brat (annoying person), (b) use phonetic spelling and/or accent marks, or (c) use rhymes to remember a word.

2.6.3. Reviewing Well

2.6.3.1. Structured Reviewing

Reviewing in carefully spaced interva1s, at first close together and then more widely spaced apart. This strategy might start, for example, with a review 10 minutes after the initial learning, then 20 minutes later, an hour or two later, a day later, 2 days later, a week later, and so on. This is sometimes called "spiralling", because the learner keeps spiralling back to what has already been learned at the same time that he or she is learning new information. The goal is "over learning" - that is, being so familiar with the information that it becomes natural and automatic.

2.6.4. Employing Action

The two strategies in this set, using physical response or sensation and using mechanical tricks, both involve some kind of meaningful movement or action. These strategies will appeal to learners who enjoy the kinaesthetic or tactile modes of learning.

2.6.4.1. Using Physical Response or Sensation

Physically acting out a new expression (e.g., going to the door), or meaningfully relating a new expression to a physical feeling or sensation (e.g., warmth).

2.6.4.2. Using Mechanical Techniques

Using creative but tangible techniques, especially involving moving or changing something which is concrete, in order to remember new target language information. Examples are writing words on cards and moving cards from one stack to another when a word is learned, and putting different types of material in separate sections of a language learning notebook.

Learners can use memory strategies to retrieve target language information quickly, so that this information can be employed for communication involving any of the four language skills. The same mechanism that was initially used for getting the information into memory can be used later on for recalling the information. Just thinking of the learner's original image, sound and image combination, action, sensation, association, or grouping can rapidly retrieve the needed information, particularly if the learner has taken the time to review the material in a structured way after the initial encounter. Memory strategies are valuable for storing and retrieving new information in the target language.

2.7. Mnemonics

Mnemonics is the overall term given to a variety of memory aids. These aids are acronyms, acrostics, rhymes, linking information by creating visual images or making up a story. Mnemonics has been recommended as appropriate for remembering vocabulary as well as dates, speeches, phone numbers, artists’ parts in drama and poems. According to Glynn, Koballa and Coleman (2003:53), the word mnemonics comes from mnemonikos (mindful) and associated with Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory, in Greek mythology. Greeks and Romans used this more than 2000 years ago but Sumerians and Babylonians applied mnemonics to the stars 4000 years ago. The ancient

people located stars easier by categorizing the stars into constellations, in which they imagined they saw patterns such as hunter (Orion) with a belt and a sword.

2.7.1. Loci Method

Glynn, Koballa and Coleman (2003:53) state that the method of loci is a classic mnemonic method which focuses on mental imagery. The word ‘loci’ comes from the plural of the Latin word ‘locus’ meaning ‘place’.

The method is associated with the Greek poet Simonides. According to one story, Simonides attended a banquet, interacted with the guests inside, and left the building. As fate would have it, the roof of the building suddenly collapsed killing everyone inside, except for Simonides. The bodies of the victims were so badly mangled that their relatives could not identify them. Simonides however, was able to identify the victims because he remembered where each person sat at the banquet table.

(Glynn, Koballa and Coleman, 2003:53) This method is very effective for remembering lists. First of all you choose a place that you know very well. Any place that you know well enough to call to mind various landmarks easily can be chosen. You must train yourself to go around your landmarks in a particular order with a route. Imagine each item which is needed to be remembered in turn at these landmarks.

Nattinger in Roland and McCarty defines this method as follows:

Loci are based on the fact that we operate ‘cognitive maps’ which are familiar sequences of visual images that can be recalled easily. These images (the loci) are usually situated along a well travelled path, but can also be objects in a familiar room, events in a well-known story or any other such familiar sequence. To memorize an item, one forms a visual image of it and places it at one of the loci in one’s imagined scene. Retrieval of these items then comes about effortlessly when the entire scene is brought back to mind.

(Nattinger in Roland and McCarty, 1998:65)

2.7.2. The Pegword Method

Scruggs and Mastropieri (2000,164) defines Pegword method as “rhyming proxies for numbers and it is used to remember numbered or ordered information”. For example:

One is bun. Two is shoe. Three is tree. Four is a door. Five is a hive. Six is sticks. Seven is heaven. Eight is gate. Nine is line. Ten is hen.

The rhyming words or “pegwords” provide visual images that can be associated with facts or events with and can help students associate the events with the number that rhymes with the pegword. Scruggs and Mastropieri (2000,164) gives example of using this method “to remember that insects have six legs, a picture can be drawn of insects on sticks (pegword for 6). A picture of spiders on gate (pegword for 8) can help students remember that spiders have eight legs”.

2.7.3. Letter Strategies

This type of strategy includes acronyms and acrostics. Acronyms create new words by merging the first letters or listing words. Scrugss and Mastropieri exemplify this as follows:

To help students remember that the countries of the Central Powers in World War One were Turkey, Austria-Hungary, and Germany, a picture can be shown of children playing TAG (acronym for Turkey, Austria-Hungary, and Germany) in Central Park (keyword for Central powers)

(Scruggs and Mastropieri, 2000:165). You can’t make words by using the first letters every time. In that case, acrostics in which the first letters of the target words are used as the first letters of other words to make a meaningful phrase. Mastropieri and Scruggs give an example as below:

If you wished to remember the names of the planets in their order from the sun, the letters would be M-V-E-M-J-S-U-N-P from which a word cannot be made. In these cases, an acrostic can be created in which

the first letters are reconstructed to represent the words in a sentence. In this case, the sentence could be ‘My very educated mother just sent us

nine pizzas’.

(Mastropieri and Scruggs, 1998:207)

2.7.4. Keyword Method

The Mnemonic Keyword Method was introduced to vocabulary teaching by Atkinson. He defines it as follows:

In general, the keyword has no relationship to the foreign word, except for the fact that it is similar in sound. The keyword method divides vocabulary learning into two stages. The first stage requires the subject to associate the spoken foreign word with the keyword, an association that is formed quickly because of acoustic similarity. The second stage requires the subject to form a mental image of the keyword "interacting" with the translation; this stage is comparable to a paired-associate procedure involving the learning of unrelated one's own knowledge. To summarise, the keyword method can be described as a chain of two links connecting a foreign word to its translation. The spoken foreign word is linked to the keyword by a similarity in sound (what I call the acoustic link), and in turn the keyword is linked to the English translation by a mental image (what I call the imagery link).

(Atkinson, 1975:821):

Atkinson (1975) proposed the keyword method as a supplementary technique for foreign language vocabulary study and reported that it is superior to rote rehearsal technique for vocabulary and strongly claims that, this method is highly useful for both foreign and native language learning.

Oxford cited in Külekci (2000; 3) also defined the keyword method as the combination of sounds and visual imagery.

This strategy combines sounds and images so that learners can more easily remember what they hear or read in the new language. The strategy has two steps. First, identify a familiar word in one's own language or another language that sounds like the new word. Second, generate a visual image of the new word and the familiar one interacting the same way- Notice that the target language word does not have to sound exactly like the familiar word (Additional pronunciation practice may be needed via the strategy of formally practising with sounds and writing systems). For example the new French word froid (cold) is linked

with a familiar word., Freud, then is imagined Freud standing outside in the cold.

(Oxford cited in Külekci, 2000:3)

According to Scruggs and Mastropieri (2000:164) “ the new word to-be learned is recoded into a keyword that is concrete (easy to picture), already familiar to the learner, and acoustically similar to the target word. The keyword is then linked to the definition in an interactive picture which shows the keyword and the definition doing

something together.”

Mastropieri and Scruggs exemplify the method as follows:

To help students remember that “barrister” is another word for lawyer, first create a keyword for the unfamiliar word, barrister. Remember, a keyword is a word that sounds like the new word and easily pictured. A good keyword for barrister is bear. Then you create picture of the keyword and the definition doing something together. It is important that these two things actually interact and are not simply presented in the same picture. Therefore, a picture of a bear and lawyer in one picture is not a good mnemonic because the elements are not interacting. A better picture would be a bear who is acting as a lawyer in a courtroom, for example, pleading his client’s innocence. we have created pictures and shown them on overhead projectors, but you could show them in other ways as well. When you practice this strategy, be certain students understand all parts of it.

Class, barrister is another word for lawyer. To remember what a barrister is, first think of the keyword for barrister: bear. What’s the keyword for barrister?[bear] Good, the keyword for barrister is bear, and barrister is a lawyer. Now [displays overhead]look at this picture of a bear acting like a lawyer. When you hear the word barrister, you first think of the keyword...?[bear] Good, and remember, what is the bear doing in the picture?[being a lawyer]. Right being a lawyer. So what does barrister mean?[lawyer] lawyer. Good.

(Mastropieri and Scruggs, 1998:207) After this application, the students would retrieve the keyword, bear; recall the interactive picture, a bear acting as a lawyer in a courtroom; and state the desired response, barrister. Students can draw this picture in their minds.

Nattinger in Roland and McCarty (1998;66) summarizes the characteristics of keyword as below:

Concrete words which one can easily form an image of seem to work best, bizarre images make the most effective associations, keywords can be invented by the student or they can be provided by the teacher without reducing the effectiveness on their recall, the techniques for forming keywords can themselves be taught, the keyword method may actually facilitate rather than interfere with pronunciation, and finally, the technique is valuable for students at both advanced and beginning levels of ability.

(Nattinger in Roland and McCarty, 1998;66)

2.8. Context Method

Knowing a word in foreign language learning includes ‘recognize it in its spoken or written form’. According to Nist and Simpson (1993:29) “ The most common strategy or approach recommended to students who have problems in determining the meaning of a word they meet during reading is to use context.” In context method words sentences or paragraphs around the unknown word help learners determining its meaning. Hycraft (1997:47)states that “The meaning can be deduced if the word takes part in a text or passage where the other words are already known”. Harmer (1993:24) emphasises the importance of giving unknown words in context:

There is a way of looking at vocabulary learning which suggests

that students should go home every evening and learn a list of fifty words ‘by heart’. Such practice may have beneficial results, of course, but it avoids one of the central features of vocabulary use, namely that words occur in context. If we are really to teach students what words mean and how they are used, we need to show them being used together with other words in context. Words do not just exist on their own: they live with other words and they depend upon each other. We need our students to be aware of this. That is why, once again, reading and listening will play such a part in the acquisition of vocabulary.

When students learn words in context they are far more likely to

remember them than if they learn them as single items. And if this were not true they would at least get a much better picture of what the words mean.

(Harmer, 1991:24)

According to Bowen and Marks (1994; 93) There are two main reasons for giving vocabulary in context. Firstly, the context can present an association for the learner that helps to trigger the recall of lexical items linked with this context. Many learners can recall vocabulary by making mental associations with situational or

contextual images. Secondly contextualizing vocabulary presents learner with a means of physical storing vocabulary items under a topic category, rather than in random or alphabetic lists.

According to Nattinger in Carter and McCarty (1988:63) there are some clues that students look for to discover the meaning of new words in context. They are topic, words in discourse and grammatical structure. Nattinger in Carter and McCarty explains as below:

First of all our guesses are guided by the topic, which in conversation is obvious from the type of social interaction involved, and which in reading may be signalled by an abstract or outline of what we are about to read. Even a title provides an effective source of clues for guessing. Secondly we are guided by the other words in the discourse to help us guess. Discourse is full of redundancy, anaphora and parallelism, and each offers clues for understanding new vocabulary. Finally, grammatical structure, as well as intonation in speech and punctuation in writing, contain further clues.

(Nattinger in Carter and McCarty, 1988:63) Nunan (1998:121) claims that encouraging learners to develop strategies for inferring the meaning of new words from the context and teaching them verbal and non-verbal clues is very important. Kurse cited in Nunan lists the suggestions for teaching written vocabulary in context as follows:

1. Word elements such as prefixes, suffixes and roots. The ability to recognise component parts of words, word families, and so on is probably the single most important vocabulary skill a student of reading in EFL can have. It substantially reduces the number of completely new words he will encounter and increase his control of the English lexicon.

2. Pictures, diagrams and charts. These clues, so obviously to the native speaker, must often be pointed out to the EFL students. He may not connect the illustration with the item that is giving him difficulty. He may also be unable to read charts and graphs in English.

3. Clues of definition. The student must be taught to notice the many types of highly useful definition clues. Among these are:

a. Parentheses or footnotes, which are the most obvious definition clues. The student can be taught to recognise the physical characteristics of the clue.

b. Synonyms and antonyms usually occur along with other clues: that is, in clauses, explanations in parentheses, and so on.

(1) is and that is (X is Y; X, that is Y) are easily recognisable signal words giving definition clues.

(2) appositival clause constructions set off by commas, which, or, or dashes (X, Y; X – Y - ; X, which is Y,; X, or Y) are also physical recognisable clues.

4. Inference clues from discourse, which are usually not confined to one sentence:

a. Example clue, where the meaning for the word can be inferred from an example, often use physical clues such as i.e., e.g., and for example.

b. Summary clues: from the sum of the information in a sentence or paragraph, the student can understand the word.

c. Experience clues: the reader can get a meaning from a word by recalling a similar situation he has experienced and making the appropriate inference.

5. General aids, which usually do not help the student with specific meaning, narrow the possibilities. These include the function of the word

in question, i.e. noun, adjective, etc. and the subject being discussed.

(Kruse cited in Nunan, 1998: 121)

2.9. Studies on Keyword Method

Many studies have been conducted on keyword Method since the early 1970’s. Most of the studies have shown that Mnemonic Keyword Method is an effective vocabulary teaching method. These studies conducted in classroom settings.

Atkinson (1975) introduced the mnemonic keyword method in second language teaching. In this study, he proposed the keyword method as a supplementary technique for improving college students’ second language vocabulary learning. In the first stage, the subject associates the spoken foreign word with the keyword, and association that is formed quickly because of the acoustic similarity between the words. In the second step, the subject forms a mental image of the keyword related with the English translation. Atkinson experimentally showed that keyword method was 50% more effective than conventional rote methods.

Atkinson and Raugh (1975) compared the effectiveness of the keyword method with a no strategy control. 120 Russian words were chosen as a target language for college students. Subjects were asked to learn the words. The target vocabulary was divided into three sub-vocabularies of 40 words each.