İçindekiler 44. Sayı Hakemleri

Gender Differences in Achievement Goals and Their Relations to Self-Reported Persistence/Effort Bulent Agbuga. ... 1-18 Influence of Teacher Perceptions of Students on Teaching High School Biology

Ebru Öztürk Akar & Ali Yıldırım ... 19-32 Prospective Teachers’ Digital Empowerment and Their Information Literacy Self-Efficacy

Buket Akkoyunlu & Ayhan Yılmaz ... 33-50 Metaphorical Images of School: School Perceptions of Primary Education Supervisors

F. Ayşe Balcı ... 51-70 Investigating Levels and Predictors of Life Satisfac-tion among Prospective Teachers

Aslı Uz Baş ... 71-88 Problem-Solving Instruction in the Context of Child-ren’s Literature and Problem Understanding Osman Cankoy... 89-110 Teaching Multicultural Counseling: An Example from a Turkish Counseling Undergraduate Program Dilek Yelda Kağnıcı ... 111-128 Mate Selection Preferences of Turkish University İbrahim Keklik ... 129-148 The Effects of Using Newspapers in Science and Technology Course Activities on Students’ Critical Thinking Skills

Esma Buluş Kırıkkaya & Esra Bozkurt ... 149-166 An Evaluation of English Textbooks in Turkish Primary Education: Students’ and Teachers’ Perceptions

Yasemin Kırkgöz ... 167-184 The Influence of the Physical Environment on Early Childhood Education Classroom Management İkbal Tuba Şahin, Feyza Tantekin Erden, & Hanife Akar ... 185-202 A Study on the Student Teachers’ Acquisition of Science Process Skills

Ayşegül Yıldırım, Yalçın Yalçın, Serap Kaya Şengören, Rabia Tanel, Murat Sağlam, & Nevzat Kavcar . 203-218

A. Rezan ÇEÇEN Adnan Erkuş Ali E. Şahin Alim Kaya Anita Pipere Arda Arıkan Arif Sarıçoban Aymil Doğan Burçin Erol

Cennet Engin Demir

Donald Kincaid Dwight C. Holliday Ercan Kiraz Erkan Tabancalı Erkut Konter Fatih Özmantar Ferhan ODABASI Ferman Konukman Fitnat Kaptan Gülşen Bağcı Kılıç Hakan Tüzün Halil Aydın Haluk Soran Hayati Akyol Inbar Dan İbrahim Yıldırım İsmail H. Demircioğlu Jale Çakıroğlu Kevin J Fitler

Maria Assunção Flores Fernandes

Matthew Peacock

Mehmet Çelik

Mustafa Ulusoy

Mustafa Zülküf Altan

Nesrin Özdener Bayar

Oylum Akkuş

Ömer Kutlu

Paşa Tevfik Cephe

Renan Sezer Senel Poyrazli Şener Büyüköztürk Yalçın Yalaki Yavuz Akpınar Yücel Kabapınar

EURASIAN JOURNAL OF EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH

A Quarterly Peer-Reviewed Journal, Year: 11 Issue: 44/ 2011 1 44 / 2011

Eurasian Journal of Educational Research (EJER) is abstracted and indexed in; Social Science Citation Index (SSCI),

Social Scisearch,

Journal Citation Reports/ Social Sciences Editon, Higher Education Research Data Collection (HERDC),

Educational Research Abstracts (ERA), SCOPUS database, EBSCO Host database, and

national index. FOUNDING EDITOR

V Hacettepe University, Ankara, TURKEY EDITORS

, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, TURKEY Ali E. Hacettepe University, Ankara, TURKEY

Penn State University, PA, USA

INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL BOARD / Ahmet Aypay,

Anita Pipere, Daugavpils University, LATVIA

Wayne State University, USA

Beatrice Adera, Penn State University, PA, USA Cem Birol, Near East University, Nicosia, TRNC Danny Wyffels, KATHO University, Kortrijk, BELGIUM

Ankara University, Ankara, TURKEY

Iordanescu Eugen, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, ROMANIA

United Arab Emirates University, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Mehmet Buldu, United Arab Emirates University, Abu Dhabi, UAE Sven Persson,

Arizona State University, USA

Yusif Mәmmәdov, Azerbaijan State Pedagogy University, Baku, AZERBIJAN

EDITORIAL OFFICE / Yeri

Publishing manager / Sahibi ve Dilek

ejer.editor@gmail.com

Tel: +90.312 425 81 50 pbx Fax: +90.312 425 81 11

Printing Date / 25.05.2011

Printing Address / Matbaa Adresi: Mat. Sit. 558 Sk. No:41 Yenimahalle-Ankara

Cover Design / Typography / Dizgi:

The ideas published in the journal belong to the authors.

Eurasian Journal of Educational Research (ISSN 1302-597X) is a quarterely peer-reviewed journal published by A

1

Gender Differences in Achievement Goals and

Their Relations to Self-Reported Persistence/Effort

Bulent Agbuga*

Suggested Citation:

Agbuga, B. (2010). Gender differences in achievement goals and their relations to self-reported persistence/effort. Egitim Arastirmalari-Eurasian Journal of

Educational Research, 44, 1-18

Abstract

Problem Statement: The assumption of the achievement goal theory is to

develop competence and the notion that students set goals for themselves for participating in physical education classes. These goals can influence their cognition, attitude and behavior. Therefore, the achievement goal theory is a major theoretical framework for research on achievement-related cognitions and behaviors in sport and physical education settings. Achievement goal research in physical education has been conducted primarily in the United States and other Western countries. Research evidence, however, suggests that social, cultural and contextual factors

-related cognition, affect and behavior.

Purpose of Study: The primary objective of this study was to examine

achievement goals and their relationship to student persistence/effort for both male and female students in physical education classes.

Methods: Two hundred and twenty-nine 8th and 11th grade Turkish

students (122 boys and 107 girls) completed questionnaires assessing their achievement goals and persistence/effort. Before running Pearson correlation and regression analyses, a one-way MANOVA and follow-up univariate F tests were conducted to determine gender differences.

Findings and Results: The results of this study showed that mastery and

performance-approach goals demonstrated significant positive predictors of persistence/effort for both gender groups. The results also showed that no differences emerged in the mean scores of achievement goals and persistence/effort between gender groups.

Conclusions and Recommendations: T

coefficients support the viability of the trichotomous model as a theoretical perspective in the assessment of student achievement goals in a physical education setting. Results of the study revealed no differences in the mean scores of achievement goals and persistence/effort between boys

* Asst. Prof. Dr., Pamukkale University, School of Sport Sciences and Technology, Denizli,

2

and girls. Mastery goals and performance-approach goals emerged as -reported persistence/effort, but their predictive power differed by gender. Overall, results of this study provide additional empirical support for the trichotomous achievement goal model in general and to Turkish students specifically in the context of school physical education. More studies are needed in this area in order to appropriately understand the motivational processes across the gender. Such information gained from this line of inquiry would not only help the development of theory but could also lead to a better understanding of gender-appropriate motivational techniques.

Keywords: achievement goals, persistence, gender differences, Turkish

students

The study of student goal orientation is critical if researchers and teachers expect to understand and enhance student achievement and performance in education settings. Over the past decade, achievement goal theory has been used as a framework for understanding and explaining student motivation, achievement-related cognitions and student behavior in a variety of achievement settings, including classrooms and in physical education (Agbuga & Xiang, 2008; Ames, 1992; Anderman & Maehr, 1994; Kaplan & Maehr, 1999; Solmon, 1996; Xiang & Lee, 2002). Achievement goals are cognitive representations of the purposes students perceive for engaging in achievement-related behaviors and the meanings they ascribe to those behaviors (Ames, 1992; Dweck, 1986; Maehr, 1984; Nicholls, 1989). Beliefs about the causes of success and failure (Dweck & Leggett, 1988), cognitive and affective responses to success and failure (Ames, 1992; Dweck & Leggett, 1988) and behavioral options based on stable orientation and situational factors (Pintrich, 2000) are some definitions of achievement goal theory. Achievement goals can influence how students approach, experience and perform in achievement settings.

Achievement goal researchers first conceptualized goal orientation as a dichotomy framework: mastery and performance goals (Ames & Archers, 1987, 1988; Ames, 1992; Dweck & Leggett, 1988). These two goals have been alternatively labeled task-involvement goals and ego-involvement goals (e.g., Maehr & Nicholls, 1980; Nicholls, 1989), learning goals and performance goals (e.g., Dweck, 1986; Elliot & Dweck, 1988), and mastery goals and ability goals (e.g., Ames, 1984; Butler, 1992). In this study, mastery goals and performance goals will be used as terminology throughout the article.

Mastery goals focus on learning, improvement and mastering skills, while performance goals focus on social comparisons and demonstration of competence. Research focusing on these two types of goals reveals that they are associated with different motivational patterns. Mastery goals are associated with adaptive motivational patterns, while performance goals are associated with maladaptive motivational patterns (Ames, 1992; Duda, 1992; Duda & Nicholls, 1992; Elliot & Dweck, 1988). Recently, this dichotomous model has been challenged by Elliot and his colleagues (Elliot, 1997; Elliot, 1999; Elliot & Church, 1997; Elliot & Harackiewicz,

1996). They have proposed a trichotomous, approach-avoidance achievement goal framework in which the mastery goals remain the same as that in the dichotomous framework. The performance goals, however, are dissected into approach and avoidance goals. While performance-approach goals focus on the attainment of favorable judgments of competence, performance-avoidance goals focus on avoiding unfavorable judgments of competence (Church, Elliot, & Gable, 2001). Classroom research supports the trichotomous framework and indicates that compared to performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals, mastery goals are more likely to be associated with adaptive motivational outcomes such as working hard for success, showing intrinsic interest in learning, attributing success to effort, using the deep cognitive strategies, self-regulated learning, persisting in the face of difficulty and positive emotions toward the task and school (Kaplan, Gheen, & Midgley, 2002; Shih, 2005). In the physical education domain, few studies applied the trichotomous model to examine student motivation, behavior and achievement (Agbuga & Xiang, 2008; Guan, Xiang, McBride, & Bruene, 2006; Xiang & Lee, 2002). Clearly, research based on a trichotomous model should be extended to the physical education setting.

The assumption of the achievement goal theory is to develop competence and the notion that students set goals for themselves for participating in physical education classes. These goals can influence their cognition, attitude and behavior. Therefore, achievement goal theory became a major theoretical framework for research on achievement-related cognitions and behaviors in sport and physical education settings. Achievement goal research in physical education has been conducted primarily in the United States and other Western countries (Agbuga, 2009; Elliot, 1999; Xiang & Lee, 2002). However, research evidence suggests that social, cultural -related cognition, affect and behavior. Xiang, Lee and Solmon (1997), for example, reported that the American students scored significantly higher on mastery goals than their Chinese counterparts, while there was no significant difference on performance goals between the two cultural groups.

An important issue that has been given little concern in physical education achievement

genders. Beam, Wiggins and Moode (2000) examined possible gender differences concerning the motivational orientations (task and ego orientations) of middle and high school athletes. They found that girls had a higher level of task orientation than boys. White and Duda (1994) examined the reliability and validity of the Task and Ego Orientation in Sport Questionnaire (TEOSQ). Two hundred and thirty-two male and female youth, high school, intercollegiate and recreational sport participants responded to the TEOSQ. They found that boys were higher in ego orientation than girls. Gill (1986) proposed that boys consistently scored higher on competitiveness and win orientation than girls did. Boys also reported more competitive activities than girls. Kim & Gill (1997), in their study of achievement goals and their correlates among Korean middle school students in physical education, reported that Korean boys scored higher than girls on perceived competence and effort/importance.

4

Furthermore, researchers in both classroom and physical education (e.g., Dweck, 1986; Elliot, McGregor, & Gable, 1999; Heckhausen, 1991; Xiang & Lee, 2002) consider persistence and effort important indications of student achievement. Persistence is defined as a continued investment in learning when obstacles are encountered, while effort refers to the overall amount of energy or work expended in the process of learning (Zimmerman & Risemberg, 1997). Students who persist and put forth effort are more likely to learn and achieve than students who lack persistence and effort. Because of the significant relationships between persistence/effort and student motivation and achievement, researchers (Dweck, 1986; Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996; Guan et al., 2006; Xiang & Lee, 2002) in both academic and physical education settings often include it in their studies. Most previous studies have been based on either a dichotomous achievement goal model or traditional classroom settings (Bouffard, Boisvert, Vezeau, & Larouche, 1995; MacIver, Stipek, & Daniels, 1991; Miller, Greene, Montalvo, Ravindran, & Nichols, 1996; Pintrich, Simith, Garcia, & McKeachie, 1993). However, these studies revealed mixed findings regarding performance goals and persistence/effort. By performing a dichotomous achievement goal model, for example, Ames (1992) reported that performance goals were related to maladaptive motivational patterns such as low persistence in the face of difficulty and the use of less effective or superficial learning strategies. However, Harackiewicz, Barron, Carter, Lehto and Elliot (1997) found that performance goals were positively associated with academic performance among college students. The major reason for these mixed findings is that performance goals were not partitioned into approach and avoidance forms of regulation (Elliot et al., 1999). In the trichotomous achievement model, the construct of performance goals is divided into approach and avoidance goals. The approach-avoidance distinction is a critical element to understanding the relationship between achievement goals and related cognitive, affective and behavioral responses. Harackiewicz, Barron, Pintrich, Elliot cal level, this distinction is a key premise of the multiple goal perspective, and accepting this distinction implies the need to revise division of the performance goal construct, the trichotomous model is assumed to

To gain a more complete understanding of the roles that social, cultural and is a need for more studies that focus on students from different social and cultural backgrounds than those from the United States and other Western countries. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to extend previous work on American student achievement goals in physical education to students from Turkey, a country with remarkably different social and cultural values and structures from the United States. Turkey provides a unique opportunity for researchers to understand gender differences in achievement goals and their persistence/effort. Specifically, the following research questions were addressed: (a) How do achievement goals within a trichotomous achievement model and self-reported persistence/effort among students in a physical education setting vary across gender? (b) What are the relationships among achievement goals and self-reported persistence/effort? and c) Do these relationships differ by gender?

Method

The Setting and Participants

A total of 229 students (122 boys and 107 girls) from two public schools in Turkey served as participants in this study. They were 111 8th graders (57 boys and 54 girls,

M age=14.05, SD=0.67) and 118 11th graders (65 boys and 53 girls, M age=17.28, SD=0 .90). All physical education classes were taught by two experienced physical

education teachers. Class size ranged from 25 to 40 students. Students had coeducational physical education classes once a week for 90 min. Participation was voluntary and permission was obtained from the institution, parents and children. Teaching and learning activities in physical education curriculum of schools in Turkey is determined by the National Ministry of Education. The traditional physical education curriculum focuses on sports such as track and field, soccer and basketball (Milli Egitim Bakanligi, 1995). The curriculum represents the most important set of guidelines for physical education teachers. Notably, the administrative structure of Turkish education is established by the National Ministry of Education, which forms one of the largest bureaucratic hierarchies in the world. The ministry itself, for example, makes the final decision affecting the administration of all schools and educational activities in Turkey (Karakaya, 2004).

Variables and Measures

The students responded to a two-part questionnaire. The first part consisted of demographic information including age, grade, gender and school. The second part assessed student achievement goals and self-reported persistence/effort in secondary physical education.

Achievement Goals. An 18-item questionnaire adapted from Duda and Nicholls

achievement goals: mastery, performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals. All items were prefaced with the

Students rated each item on a seven-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all true for me) to 7 (very true for me). Examples of the six items assessing mastery goals were,

items assessing

performance-Self-Reported Persistence/Effort -reported

persistence/effort in their physical education classes. This questionnaire was adapted from Fincham, Hokoda and Sanders (1989) and Xiang and Lee (2002). Again, Students rated each item on a seven-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all true for

6

The self-report measures on student achievement goals (mastery, performance-approach, performance-avoidance) and persistence/effort were all modified from previous research. They yielded reliable and valid scores with American students (Duda & Nicholls, 1992; Elliot, 1999; Elliot & Church, 1997, Fincham et al., 1989; Xiang & Lee, 2002). Participants in the present study were Turkish students in secondary physical education. Therefore, several steps were taken to preserve the validity and reliability of these measures.

First, all questionnaire items were translated to Turkish by the author, who was fluent in Turkish and English. To control translation quality, a panel of three other bilingual (Turkish/English) experts in the field of physical education was invited to evaluate item consistency between the English and Turkish versions of the questionnaire. The instrument, with a bilingual format, was mailed to each panel member. The panel members were encouraged to record their comments and suggestions if they believed the translation was inconsistent. They found no inconsistencies.

Second, a pilot study was run with 39 nonparticipating students to assess whether the language in the translated questionnaire was appropriate for Turkish students in secondary physical education. Students raised no questions while completing the questionnaires.

Third, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on items measuring (mastery, performance-approach and performance-avoidance) proposed by the

trichotomous framework. s (e.g., Hoyle &

Panter, 1995; Hu & Bentler, 1999), multiple fit indexes were employed to assess the adequacy of the measurement models. Indices used to determine the goodness-of-fit included: (a) the chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio ( 2/df), for which values less

than 3.0 suggest a good fit (McIver & Carmines, 1981), (b) the comparative fit index (CFI), for which values larger than .90 indicate a good fit, (c) the Bentler-Bonett non-normed fit index (NNFI), for which values larger than .90 indicate a good fit and (d) the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), for which .06-.08 is considered an acceptable fit, while .08-.10 is considered a marginal fit (Browne & Gudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1995). Data were analyzed using AMOS 5.0 (Analysis of Moment Structures) and the models were estimated using the maximum likelihood method. The results indicated three distinct achievement goals in the data set. All indices ( 2/df=1.87, CFI=.90, NNFI=.86, and RMSEA=.062) represent an acceptable fit

between the three-factor model and the data. As a result, scales of mastery, performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals were constructed by averaging the items on the sca alphas for the three scales were .73, .73

and .74, respectively, indicating acceptable internal consistency (Nunnally, 1978). Finally, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to examine the factorial validity of self-reported persistence/effort measures. For the self-reported persistence/effort measures, the exploratory factor analysis yielded a single factor

with an eigenvalue greater than 1, accounting for 46.07 percent of the variance (Table 1). All items loaded higher than .40 on the factor. Consequently, an overall score for the self-reported persistence/effort scale was computed by averaging the items on

Table 1

Factor Analysis of Self-Reported Persistence/Effort

Self-Reported Persistence/Effort Items Factor 1 When I have a trouble performing some skills, I go back and practice. ,56 Regardless of whether or not I like the activities, I work my hardest to do them. ,72 When something that I am practicing is difficult, I spend extra time and effort

trying to do it right. ,65

I try to learn and to do well, even if the activity is boring. ,76 I put a lot effort into preparing for skill tests. ,65 I work very hard to prepare for our skills tests. ,74 I work hard to do well even if I do not like what we are doing. ,80 I always pay attention to my teacher. ,48

Eigenvalue 3,68

% Variance 46,07

Note. Factor 1=Persistence/effort Procedure

All data were collected during regularly scheduled physical education classes. The questionnaires were administered to intact classes by the author. Students were told that there were no right or wrong answers and that they could skip any questions if they did not feel comfortable answering them. Students were also informed that information in the survey would be kept confidential and their teachers would not have access to their responses. To ensure independence of oud to the students and they were encouraged to answer as truthfully as they could. Students were encouraged to ask questions if they had difficulty understanding instructions or items in the questionnaire. Students raised no questions while completing the questionnaires, which took approximately 30 minutes to administer.

Results

Gender Differences on Mean Scores of Variables

As indicated in Table 2, the mean scores of the mastery, performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals as well as the self-reported persistence/effort were above the midpoint of the scale (i.e., 4), suggesting that both boys and girls in secondary schools endorsed all three achievement goals and perceived that they put forth effort and persisted in their physical education classes.

8

Table 2

Descriptive Data and Correlations for Achievement Goals and Self-Reported Persistence/Effort M SD 1 2 3 4 Boys (n = 122) 1. Mastery goals 6,32 ,65 1 ,440** ,366** ,440** 2. Performance-approach goals 5,49 1,01 1 ,451** ,501** 3.Performance-avoidance goals 4,88 1,10 1 ,334** 4.Self-reported persistence/effort 5,13 1,28 1 Girls (n = 107 ) 1. Mastery goals 6,12 ,93 1 ,587** ,551** ,626** 2. Performance-approach goals 5,24 1,32 1 ,684** ,688** 3.Performance-avoidance goals 5,14 1,13 1 ,498** 4.Self-reported persistence/effort 5,05 1,36 1 **p < 0.01 (2-tailed)

To determine gender differences in achievement goals and self-reported persistence/effort, a one-way MANOVA was conducted on mean scores of these variables. Prior to the MANOVA analysis, the assumption of homogeneity of covariance was examined using the box M test. The results revealed the assumption was not met (box M=25.909, F=2.542, p

evaluate multivariate significance of the main effect and interactions (Olson, 1979; Tabachnic & Fidell, 1996). The MANOVA analysis yielded a significant main effect

F (4, 224)=4.61, p 2=.076. Follow-up

univariate F tests, however, revealed no significant gender differences on mastery goals, F (1, 227)=3.48, p= 2=.015, performance-approach goals, F (1, 227)=2.51,

p= 2 =.011, performance-avoidance goals, F (1, 227)=3.13, p= 2=.014 and

self-reported persistence/effort, F (1, 227)=.20, p= 2=.001.

Relationships Among Variables by Gender

Pearson product-moment correlations were calculated separately for each gender to identify significant relationships among achievement goals and self-reported persistence/effort (see Table 2). A similar pattern of the relationships was observed for boys and girls. Mastery goals, approach goals, performance-avoidance goals and self-reported persistence/effort were all positively related to one another. Also, t

self-reported persistence/effort, hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted by gender. Considering the previous research findings that mastery goals are more strongly related to persistence/effort than performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals (Cury, Da Fonseca, Rufo, Peres, & Sarrazin, 2003; Elliot, 1999), for both analyses, the mastery goal was entered first, then the performance-approach goal, and last the performance-avoidance goal. As shown in Table 3, mastery goals (boys: =.256, p < .001; girls: =.350, p < .001) and performance approach goals (boys: =.351, p < .001; girls: =.514, p < .001) emerged as significant positive predictors of persistence/effort for boys and girls. The two goal predictors

explained 31 percent -reported persistence/effort for

boys and 53 percent for girls, respectively. However, the performance-avoidance goals did not make a significant contribution to the prediction model (boys: =.082, p > .05; girls: =-.046, p > .05). Table 3 -Reported Persistence/Effort Boys Girls Variable R2 R2 R2 R2 Step 1 MG .194 .194** .440** .392 .392** .626** Step 2 MG .273** .339** PApG .311 .117** .380** .548 .156** .488** Step 3 MG .256** .350** PApG .351** .514** PAvG .316 .005 .082 .549 .001 -.046

Note. MG=mastery goals, PApG=performance-approach goal,

PAvG=performance-avoidance goals; R2 values are cumulative, with each

incremental step adding to the variance explained; ** p < .001. Conclusions and Recommendations This study examined 8th and 11th

achievement goals and their relationship to self-reported persistence/effort in physical education classes. Consistent with the findings reported by Elliot (1999) and Elliot and Church (1997) in academic and university settings, the results of the CFA goal measures were valid and reliable. Scores from the mastery goals, performance-approach and performance-avoidance factors exhibit acceptable psychometric

10

properties of validity. All fit indexes are in the acceptable range, indicating that the trichotomous achievement goal scale produced valid scores and each of the three achievement goals represents a distinct construct. This finding supports the viability of the trichotomous achievement model as a theoretical perspective in the assessment of student achievement goals and related cognition, affect and behaviors in a Turkish physical education setting.

The results of this study revealed no differences in the mean scores of achievement goals and persistence between boys and girls in secondary physical education. This finding is inconsistent with American studies indicating that boys were more likely than girls to emphasize performance goals, while girls were more likely to score higher on mastery goals than their male counterparts (Beam et al., 2000; Duda, Olson, & Templin, 1991; Middleton & Midgley, 1997). One possible explanation might be that both boys and girls in this study viewed their physical education curriculum to be gender appropriate. According to Turkish National Education Policy, a non-discrimination education is an essential tool for achieving the goals of equality of access to and attainment of educational qualifications (Milli Egitim Bakanligi, 1995). Therefore, both boys and girls must perform sport-related skills such as track and field, basketball, volleyball and soccer between their entrance into elementary school and graduation from high school. Another explanation might be that gender differences in achievement goals and persistence do not emerge until students begin to consider future educational and occupational plans. Indeed, in Turkey, 11th grade represents a critical period of schooling in which students have to begin to prepare for the national university entrance examination. This examination requires students to master content knowledge in their classes including science, math, Turkish and social sciences. In addition, university admission is based on a student secondary school grade point average. These educational obligations may require both boys and girls to master the content in all the subject areas including physical education and at the same time study hard throughout secondary school.

Another purpose of the present study was to examine the relationship between -reported persistence/effort. Simple correlations revealed that for boys and girls, mastery, performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals were positively related to their self-reported persistence/effort in physical education classes. The results of hierarchical multiple regressions further confirmed the pattern of the relationships with one exception. For both genders, performance-avoidance goals were not a significant predictor of their self-reported persistence/effort. This result is not surprising since performance-avoidance goals are negatively related or unrelated to persistence and effort (Elliot et al., 1999). Students who endorse performance-avoidance goals, for example, are likely to see achievement settings as a risk to their perceived ability and therefore may try to avoid exerting effort and persisting in those settings (Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996).

In conclusion, the present study applied the trichotomous achievement goal model to the examination of achievement goals and their relations to self-reported persistence/effort among Turkish students in physical education at school. The support the viability of the

trichotomous model as a theoretical perspective in the assessment of student achievement goals in a physical education setting. The results of the study revealed no differences in the mean scores of achievement goals and persistence/effort between boys and girls. Mastery goals and performance-approach goals emerged as -reported persistence/effort, but their predictive power differed by gender. Overall, the results of this study provide additional empirical support for the trichotomous achievement goal model in general and to Turkish students specifically in the context of school physical education. More studies are needed in this area to appropriately understand the motivational processes across genders. Such information would not only help the development of theory but could also lead to a better understanding of gender-appropriate motivational techniques.

References

Agbuga, B. (2009). Reliability and validity of the trichotomous achievement goal model in an elementary school physical education setting. Egitim

Arastirmalari-Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 37, 17-31.

Agbuga, B., & Xiang, P. (2008). Achievement goals and their relations to self-reported persistence/effort in secondary physical education: A trichotomous achievement goal framework. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 27, 179-191.

Ames, C. (1984). Competitive, cooperative, and individualistic goal structures: A motivational analysis. In R. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation in

education (Vol. 1, pp. 177-207). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of

Educational Psychology, 84, 261-272.

school learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79, 409-414.

arning strategies and motivation processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 260-267.

Anderman, E., & Maehr, M. (1994). Motivation and schooling in the middle grades.

Review of Educational Research, 64, 287-310.

Beam, L., Wiggins, M. S., & Moode, F. M. (2000). Task and ego motivational in middle and high school athletes: A gender by school comparison.

KAHPERD Journal, 2, 15-17.

Bouffard, T., Boisvert, J., Vezeau, C., & Larouche, C. (1995). The impact of goal orientation on self-regulation and performance among college students.

British Journal of Educational Psychology, 65, 317-329.

12

Butler, R. (1992). What young people want to know when: Effects of mastery and ability goals on interest in different kinds of social comparisons. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 934-943.

Church, M. A., Elliot, A. J., & Gable, A. L. (2001). Perceptions of classroom environment, achievement goals and achievement outcomes. Journal of

Educational Psychology, 93(1), 43-54.

Cury, F., Da Fonseca, D., Rufo, M., Peres, C., & Sarrazin, P. (2003). The trichotomous model and investment in learning to prepare for a sport test: A mediational analysis. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 73, 529 543.

Duda, J. L. (1992). Motivation in sport settings: a goal perspective approach. In: Roberts G. (Ed). Motivation in Sport and Exercise. Champaign, ILL: Human Kinetics, (pp. 57-92).

Duda, J. L., & Nicholls, J. (1992). Dimensions of achievement motivation in schoolwork and sport. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 290-299.

Duda, J. L., Olson, L. K., & Templin, T. J. (1991). The relationship of task and ego orientation to sportsmanship attitutes and the perceived legitimacy of injusious acts. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 62, 79-87.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41, 1040-1048.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. A. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256-273.

achievement motivation: A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. In M. L. Maehs & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.), Advances in

motivation and achievement (Vol. 10, pp. 243-279). Greenwich, CT:JAI Press.

Elliot, A. J. (1999). Approach and avoidance motivation and achievement goals.

Educational Psychologist, 34, 169-189.

Elliot, A. J. & Church, M. A. (1997). A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 218-232.

Elliot, A. J., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (1996). Approach and Avoidance Achievement Goals and Intrinsic Motivation: A Mediational Analysis. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 461-475.

Elliot, A. J., McGregor, H. A., & Gable, S. (1999). Achievement goals, study strategies, and exam performance: A mediational analysis. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 76, 628-644.

Elliot, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 5-12.

Fincham, F. D., Hokoda, A., & Sanders, R., Jr., (1989). Learned helplessness, test anxiety, and academic achievement: A longitudinal analysis. Child

Gill, D. L. (1986). Competitiveness among females and males in physical activity classes. Sex Roles, 15, 233-247.

Guan, J. M., Xiang, P., McBride, R. E., & Bruene, A. (2006). Achievement goals, social goals, -reported persistence and effort in high school physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 25, 58 74. Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Carter, S. M., Lehto, A. T., & Elliot, A. J. (1997).

Determinants and consequences of achievement goals in the college classrooms: Maintaining interest and making the grade. Journal of Personality

and SocialPsychology, 73, 1284-1295.

Harackiewicz, J., Barron, K. E., Pintrich, P. R., Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2002). Revision of achievement goal theory: Necessary and illuminating. Journal of

Educational Psychology, 94, 638-645.

Heckhausen, H. (1991). Motivation and action. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Hoyle, R. H., & Panter, A. T. (1995). Writing about structural equation models. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 158 176). London: Sage.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation

Modeling, 6, 1 55.

Kaplan, A., Gheen, M., & Midgley, C. (2002). Classroom goal structure and student disruptive behavior. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72, 191-211. Kaplan, A., & Maehr, M. L. (1999).Achievement goals and student well-being.

Contemporary Educational Psychology, 24, 330-358.

of their Professional responsibility. Educational Studies, 30, 195 216.

Kim, B. J., & Gill, D. L. (1997). A cross-cultural extension of goal perspective theory to Korean youth sport. Journalof Sport and Exercise Psychology, 19, 142-155 MacIver, D., Stipek, D., & Daniels, D. (1991). Explaining within-semester changes in

student effort in junior high school and senior high school courses. Journal of

Educational Psychology, 83, 201-211.

Maehr, M. L. (1984). Meaning and motivation: Toward theory of personal investment. In R.E. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation in

education (Vol. 1, pp. 115 144). New York: Academic Press.

Maehr, M. L.., & Nicholls, J. G. (1980). Culture and achievement motivation: A second look. In N. Warren (Ed.), Studies in cross cultural psychology (pp. 221-267). New York: Academic Press.

Middleton, M., & Midgley, C. (1997). Avoiding the demonstration of lack of ability: An underexplored aspect of goal theory. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 710-718.

Miller, R. B., Greene, B. A., Montalvo, G. P., Ravindran, B., & Nichols, J. D. (1996). Engagement in academic work: The role of learning goals, future

14

consequences, pleasing others, and perceived ability. Contemporary

Educational Psychology, 21, 388-422.

Milli Egitim Bakanligi. (1995). Ilkogretim okullari, lise ve dengi okullar beden egitimi dersi

ogretim programlari [Physical education curriculums for primary and

secondary schools]. Istanbul: Milli Egitim Basimevi.

Nicholls, J. G. (1989). The competitive ethos and democratic education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Olson, C.L. (1979). Practical considerations in choosing a MANOVA test statistic: A rejoinder to Stevens. Psychological Bulletin, 86, 1350 1352.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). An achievement goal theory perspective on issues in motivation terminology, theory, and research. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 92-104.

Pintrich, P. R., Simith, D., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1993). Reliability and predictive validity of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53, 801-813.

Shih, S. (2005). Taiwanese Sixth Graders' Achievement Goals and Their Motivation, Strategy Use, and Grades: An Examination of the Multiple Goal Perspective.

Elementary School Journal, 106, 39-59.

perceptions of a physical education setting. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 731-738.

White, S. A., & Duda, J. L. (1994). The relationship of gender, level of sport involvement, and participation motivation to task and ego orientation. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 25, 4-18.

Xiang, P., & Lee, A. (2002). Achievement goals, perceived motivational climate, and stu -reported mastery behaviors. Research Quarterly for Exercise and

Sport, 73, 58-65.

Xiang, P., Lee, A., & Solmon, M. A. (1997). Achievement goals and their correlates among American and Chinese students in physical education: A cross-cultural analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 28, 645-660.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Risemberg, R. (1997). Self-regulatory dimensions of academic learning and motivation. In G. Phye (Ed.), Handbook of academic learning (pp. 105-125). New York: Academic.

Problem Durumu: Ba leri revi aynen isteklerini B .

16 k/gayret Pearson korelasyonu ve -. Bulgular ve S

2/df = 1.87, CFI = .90, NNFI = .86, and RMSEA

tablosundaki p M = 25.909, F = 2.542, p = .005). Bund F (4, 224) = 4.61, p 2 hedeflerde, F (1, 227) = 3.48, p = 2 F (1, 227) = 2.51, p = 2 F (1, 227) = 3.13, p = 2 = .014, F (1, 227) = .20, p = 2 tur. Halbuki, = .256, p = .350, p (erkekler: = .351, p = .514, p < .001) belirleyici

statistik ana

Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, Issue 44, Summer 2011, 19-32

19

Influence of Teacher Perceptions of Students on

Teaching High School Biology

*Suggested Citation:

perceptions of students on teaching high school biology. Egitim

Arastirmalari-Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 44, 19-32.

Abstract

Problem Statement: The research question guiding the current study was

Purpose of the Study: The purpose of this study was to determine how teacher perceptions of students influenced the way teachers teach biology Methods: A survey questionnaire was administered to 685 biology teachers sampled through stratified random and cluster random sampling strategies. Data gathered on teaching methods, techniques, instructional of their students were analyzed through inferential statistics (chi-square and cross tabulation).

Findings and Results: The results highlighted differences in the way biology was taught in classes of teachers with different beliefs and with different perceptions of students. They use different teaching methods, techniques, and instructional materials.

Conclusions and Recommendations:

should be examined as a means to improve instructional practices for science education not just in Turkey but also in other countries. In order to into the way teachers think and act in the classroom, policy capturing, repertory grid technique and process tracing, questionnaires, semi-structured interviews and classroom observations should be used.

Keywords: teacher perceptions, students, teaching biology, teaching

methods, instructional materials

* Ankara, TURKEY,

akar_e@ibu.edu.tr

** Prof.Dr., Middle East Technical University Faculty of Education, Ankara, TURKEY, aliy@metu.edu.tr

-existing knowledge and beliefs about teaching, learning, learners and subject matter facilitate the realization of desired educational goals and support teacher learning for this purpose (Davis, 2003; Pajares, 1992; Shavelson & Stern, 1981). Tobin (1987) and Calderhead (1996) identify teacher beliefs about how students learn and what they ought to learn as having the greatest impact on implementation of educational innovations. Cronin-Jones (1991) also states that (1993) suggests that the beliefs of teachers are associated with their instructional actions.

not be overlooked if innovations that will impact student learning are to be developed (Barab & Luehmann, 2003; Czerniak, Lumpe & Haney, 1999; Clark & Peterson, 1986; Rigano & Ritchie, 2003; Schneider, Krajcik & Blumenfeld, 2005; Tobin, 1993; Verjovsky & Waldegg, 2005). It is widely accepted that a change in teacher beliefs results in the transformation of science teaching (Haney, Lumpe, Czerniak & Egan, 2002; Yerrick, Parke & Nugent, 1997).

Among the factors identified in the literature as shaping what teachers do in the personal pedagogical beliefs, beliefs and perceptions about students and their needs, beliefs and perceptions of the nature of science and the curriculum. Studies on classroom culture, beliefs about teaching and learning and contextual concerns, instructional goal

concerns are too numerous to list (Calderhead, 1996; Crawley & Salyer, 1995; Cronin-Jones, 1991; Czerniak, Lumpe & Haney, 1999; Davis, 2003; Deemer, 2004; Dreyfus, Jungwirth & Tamir, 1985; Fang, 1996; Fetters, Czerniak, Fish & Shawberry, 2002; Gess-Newsome, 2001; Gess-Newsome & Lederman, 1995; Haney, Lumpe, Czerniak & Egan, 2002; Hawthorne, 1992; Hipkins, Barker & Bolstad, 2005; Kagan, 1992; Kang & Wallace, 2004; Keys & Bryan, 2001; LaPlante, 1997; Lederman, 1999; Lewthwaite, & Barab, 2003; Tobin, 1987; Veal, 2004).

The current science education curricula for Turkish secondary schools aim at providing students with the scientific knowledge and skills necessary for self-directed

life-be able to use scientific knowledge and skills in daily life, to have an appreciation of a healthy life and to know about and begin to understand the natural world. During instruction, students are expected to be active individuals that can reflect on science and scientific inquiries and/or interpret the results of such inquiries. Experiencing and searching are promoted and student-centred activities are suggested and reinforced by the Ministry of National Education (MONE, 2007, 2009). The role of the biology teacher is defined as that of a facilitator or a guide who is there to help students comprehend the subject matter optimally, using all five of their senses with an emphasis on active involvement.

constraints on teachers trying to carry out the intended educational tasks (Dindar, 2001; Ekici, 1996; Erten, 1993; Turan,

Eurasian Journal of Educational Research 21 average number of students in the classroom, the physical facilities of the schools, a budget dedicated to biology courses, and familiarity with the teaching methodology are the factors identified

teaching. Insufficient laboratory conditions, crowded classrooms and time limitations were found to be the main reasons for using a laboratory only once or twice a month ran (1996) and Yaman (1998) also point to insufficient facilities and the physical condition of schools as problems that can hinder effective biology education. Author 1 (1999) points to the large amounts of content to be covered and time as the overriding constraints to carry out desirable educational tasks such as laboratory studies. Yet, the role that

play in determining the way teachers teach biology is not clear. The question of the d their perceptions of students shape the way they teach is critical, since the success of instruction may depend on the way teachers perceive their students. Therefore, the purpose of this research is to investigate how teacher perceptions of students influence the way biology is taught in Turkish high

Method

Research Design

A survey questionnaire consisting of open-ended and structured questions was designed to gather data on teaching methods, techniques, instructional materials their perceptions of their students. Related literature was reviewed and curriculum characteristics were examined to prepare the questions for this questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of five parts and included 34 items. Prior to administration, the questionnaire was submitted to a

knowledgeable about the purpose of the high school biology curriculum and the purpose of the questionnaire. They were asked to review and judge the items in the questionnaire and to determine if they adequately sampled the domain of interest and how closely their content corresponded to the objectives and explanations for the suggestions, the questionnaire was pilot tested in five high schools in Ankara. Eighteen biology teachers in these schools were asked if the items on the questionnaire were clear and understandable, and if there was any necessary changes that needed to be made to the questionnaire as a whole. In order to check the reliability, short interviews with the teachers were conducted immediately after the application of the questionnaire

compared. Accordingly, revisions and additions were made to enhance the clarity of the questions.

The quantitative data used in this study were collected through the structured questions in the third and fourth parts of this questionnaire. These questions were related to the teaching methods, techniques and instructional materials used during

their students. The questions related to the teaching methods, techniques and instructional materials were drawn fro

often do you use the listed teaching methods and techniques, i.e. lecture, questioning, discussion, demonstration, field trips and observation, and instructional technology in your you use the listed instructional materials, i.e. living things (animals and plants), examples and models (DNA model, etc.), films, overhead projectors, slides, diagrams, graphs, etc., and written materials (words, texts, formulas, signs) in your hers were required to mark their responses, i.e. yes, moderately, and no, about their beliefs and perceptions of students to the following six structured questions: are your students interested in biology? Do your students see biology as an important course? Do your students

about biology? Can your students connect lesson content to daily life?

Sample

Considering the number of schools (2328 schools in total; 1559 public, 352 private/foundation, and 417 Anatolian high schools) and making the assumption that there are at least two biology teachers working in each school, the size of the sample population was estimated to be 4656 teachers. Since it was thought to be hard to reach all the teachers, a two-step sampling strategy was followed. Sample size was set to 600 biology teachers taking into account return rates for questionnaires and the statistical analyses needed to be conducted using the data collected. This required that questionnaires were sent to 300 schools. Stratified random and cluster random sampling strategies were followed to select the schools and to reach 600 biology teachers. Schooling level (DPT Report, 1998) was used as the main criteria to build five strata from which fifteen cities were randomly selected. Then, questionnaires were sent to randomly-selected schools in these cities. Education Research and the Development Directorate (ERDD) facilitated this process. The return rates for the questionnaires showed that the questionnaires were copied and answered by more teachers than expected.

The majority of the teachers responding to the questionnaire was female (60.9%) and had 10 to 15 years of teaching experience (30%). Over one-fourth of the teachers (26.5%) had six to 10, 18.2% had 21 or more, 17.3% had 16 to 20, and 8.1% had one to five years of teaching experience. One-third (32.1%) of the teachers fell in the age range of 41 and over. 24.5% of the teachers were between 36 and 40, and 23.5% were between 31 and 35. One fifth of the sample (20%) was 30 or younger.

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyse the data collected using structured questions. Means

calculated using frequency distributions. Cross-tabulation and chi-square tests were the way they teach biology. The percentages in the results tables show the interrelationship between variables defined in the rows and columns

.

Eurasian Journal of Educational Research 23 Results

and perceptions of students and the use of tea

the perceptions of students and use of instructional materials.

Relationship between teacher beliefs and perceptions of the students and the use of teaching methods and techniques

perceptions of students. As shown in Table 1, 77.9% of the teachers who mentioned that their students were interested in biology used demonstrations more (44.19%

, X2 (df=8, n=645)

= 26.75, p<0.001. Likewise, 38.45% of the teachers who mentioned that their students were interested in biology also used field trips and observations more (31.92%

, X2 (df=8, n=634) =

52.82, p<0.001.

The teachers who stated that their students actively participated in the lessons used the disc

X2 (df=8, n=649)=29.84,

p<0.001 ,

more often than teachers who moderately agreed or disagreed that students actively participated in lessons.

Table 1.

Use of Frequency of Teaching Methods and Techniques by Beliefs and the Perceptions of Students in Percentages I

Beliefs-perceptions of students Teaching method Demonstration Students are interested in biology Never

(n=45) Rarely (n=148) Sometimes (n=287) Often (n=134) Always (n=31) Yes 5.24 16.85 44.19 28.84 4.87 Moderately 7.78 27.78 44.44 15.28 4.72 No 16.67 16.67 50 11.11 5.56

Field trips-observations Students are interested in biology Never

(n=192) Rarely (n=269) Sometimes (n=140) Often (n=27) Always (n=6) Yes 18.08 43.46 31.92 4.61 1.92 Moderately 37.54 42.86 15.13 4.20 0.28 No 64.71 17.65 17.65 0 0

Discussion Students actively participate in lessons Never

(n=4) Rarely (n=62) Sometimes (n=343) Often (n=176) Always (n=64) Yes 0.48 6.22 46.41 30.62 16.27 Moderately 0.48 10.41 56.17 25.67 7.26 No 3.7 22.22 51.85 22.22 0

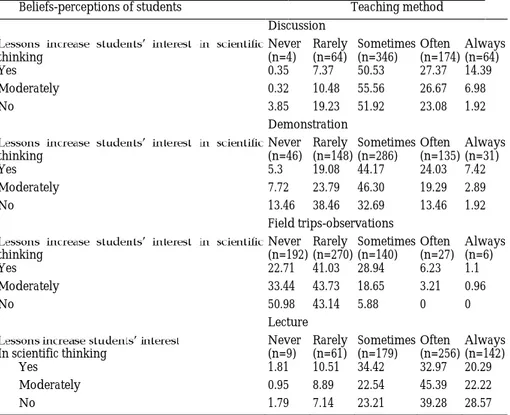

Table 2 shows the interrelationship between teacher beliefs and perceptions of students and the use frequency of teaching methods in percentages. Teachers who believed that biology teaching methods and techniques of discussion more often than other teachers during instruction, X2 (df=8, n=652) =29.17, p<0.001. These teachers also used demonstration and field

trips and observations more often in their classes, X2 (df=8, n=646) =24.07, p<0.001, and X2

(df=8, n=635)=33.25, p<0.001 respectively. 92.29% of these teachers used discussions (50.53% ,

, s and observations

of the teachers who believed that biology lessons increased thei

field trips and observations when teaching biology. Yet, teachers who lectured more were the scientific thinking, learning and research,X2 (df=8, n=647) =16.76, p=0.03. 91.06% of these

, other teachers.

Table 2.

Use of Teaching Methods and Techniques by Beliefs and the Perceptions of Students II

Beliefs-perceptions of students Teaching method Discussion

thinking Never (n=4) Rarely (n=64) Sometimes (n=346) Often (n=174) Always (n=64) Yes 0.35 7.37 50.53 27.37 14.39 Moderately 0.32 10.48 55.56 26.67 6.98 No 3.85 19.23 51.92 23.08 1.92

Demonstration

thinking Never (n=46) Rarely (n=148) Sometimes (n=286) Often (n=135) Always (n=31) Yes 5.3 19.08 44.17 24.03 7.42 Moderately 7.72 23.79 46.30 19.29 2.89 No 13.46 38.46 32.69 13.46 1.92

Field trips-observations

thinking Never (n=192) Rarely (n=270) Sometimes (n=140) Often (n=27) Always (n=6) Yes 22.71 41.03 28.94 6.23 1.1 Moderately 33.44 43.73 18.65 3.21 0.96

No 50.98 43.14 5.88 0 0

Lecture

In scientific thinking Never (n=9) Rarely (n=61) Sometimes (n=179) Often (n=256) Always (n=142) Yes 1.81 10.51 34.42 32.97 20.29 Moderately 0.95 8.89 22.54 45.39 22.22 No 1.79 7.14 23.21 39.28 28.57

Eurasian Journal of Educational Research 25 In T

life are examined together with the use frequency for discussion (X2 (df=8, n=648)

=28.73, p<0.001) and demonstration (X2 (df=8, n=643)=22.03, p<0.001) methods and

techniques. It can be seen that teachers who agreed that students can relate lesson content to daily life used these methods and techniques more often than other . The vast majority (93.72%) of these

,

Table 3.

Use of Teaching Methods by Beliefs and the Perceptions of Students III

Beliefs-perceptions of students Teaching method Discussion

Students can connect lesson content to daily life

Never (n=4) Rarely (n=64) Sometimes (n=243) Often (n=173) Always (n=64) Yes 0 6.28 52.3 26.78 14.64 Moderately 0.8 10.7 54.13 26.67 7.73 No 2.94 26.5 44.12 26.47 0 Demonstration Students can connect lesson

content to daily life Never (n=46) Rarely (n=147) Sometimes (n=286) Often (n=133) Always (n=31) Yes 4.53 17.28 51.03 19.75 7.407 Moderately 8.19 25.96 40.44 21.86 3.55 No 14.71 29.41 41.18 14.71 0

Relationship between teacher beliefs and perceptions of students and the use of instructional materials

Almost half (46.33%) of the teachers who believed that students were interested ,

X2 (df=8, n=623) =25.83,

p<0.001 (see Table 4). It was also found that 77.85% of the teachers who stated that ,

X2 (df=8, n=642) =19.63, p=0.01.; 95.79% used examples and models (17.19%

, X2 (df=8, n=653) =17.54, p=0.02;

, X2

Table 4.

Use of Instructional Materials by Beliefs and the Perceptions of Students I

Beliefs-perceptions of students Instructional material Films

Students are interested in biology Never

(n=285) Rarely (n=94) Sometimes (n=144) Often (n=71) Always (n=29) Yes 34.75 18.92 28.19 11.58 6.56 Moderately 53.03 12.39 19.6 11.53 3.46 No 64.71 11.76 17.65 5.88 0

Living things (animals and plants)

interest in scientific thinking Never (n=52) Rarely (n=121) Sometimes (n=297) Often (n=118) Always (n=54) Yes 5.71 16.43 49.64 21.43 6.78 Moderately 9.03 19.03 44.52 17.74 9.67 No 15.38 30.77 38.46 5.77 9.62

Examples and models Biology lessons increase

interest in scientific thinking Never (n=14) Rarely (n=19) Sometimes (n=133) Often (n=271) Always (n=216) Yes 2.11 2.11 17.19 40.35 38.25 Moderately 2.54 2.54 22.22 42.86 29.84 No 0 9.43 26.42 39.62 24.53

Films Biology lessons increase stud

interest in scientific thinking Never (n=286) Rarely (n=94) Sometimes (n=144) Often (n=71) Always (n=29) Yes 37.04 13.7 27.78 14.44 7.04 Moderately 50.33 17.22 20.86 8.61 2.98 No 65.38 9.61 11.54 11.54 1.92

As shown in Table 5, 76.47% of the teachers who agreed that students could relate ,

2 (df=8, n=639) =20.06, p=0.01. 57.64% used overhead projector

, X2 (df=8, n=613)

=45.91, ,

X2 (df=8, n=638) =18.82, p=0.02 more often than other

Eurasian Journal of Educational Research 27

Table 5

Use of Instructional Materials by Beliefs and the Perceptions of Students II

Beliefs-perceptions of students Instructional material

Living things (animals and plants) Students can connect lesson content to

daily life Never (n=52) Rarely (n=119) Sometimes (n=296) Often (n=117) Always (n=55) Yes 5.88 17.65 46.64 19.75 10.08 Moderately 7.90 19.62 46.05 18.26 8.17 No 26.47 14.71 47.06 8.82 2.94

Overhead projector and slides Students can connect lesson content to

daily life Never (n=185) Rarely (n=99) Sometimes (n=149) Often (n=105) Always (n=75) Yes 24.02 18.34 23.58 18.34 15.72 Moderately 33.99 11.61 26.06 17.28 11.05 No 32.26 51.61 9.67 6.45 0

Diagrams, graphs, etc. Students can connect lesson content to

daily life Never (n=37) Rarely (n=67) Sometimes (n=153) Often (n=214) Always (n=167) Yes 7.85 7.85 19.42 33.88 31 Moderately 4.12 11.54 26.1 33.79 24.5 No 9.37 18.75 34.38 28.13 9.38

Conclusions and Discussion

The results of this study have shown that teacher beliefs and perceptions influence the process of teaching biology in different ways. Teachers with different beliefs and perceptions of their students use different teaching methods and techniques, as well as instructional materials. In the classes of teachers who believed learning and research and that their students were interested in biology, could relate lesson content to daily life. These teachers also actively participated in the lessons using the teaching methods and techniques of demonstrations, field trips, observations, and discussions more often than the other teachers. In addition, these teachers also used films, living things, examples and models, overhead projectors and slides, diagrams and graphs more often in teaching biology.

The underlying assumption while investigating the influence of teacher beliefs on their teaching practices was a

belief-their students determine belief-their classroom actions (Clark & Peterson, 1986; Czerniak, Lumpe & Haney, 1999; Haney, Lumpe, Czerniak & Egan, 2002). However, the relationship identified between teacher beliefs regarding their students and the teaching methodologies and instructional materials they used in biology classes

decisions about their classroom actions.

The results of this study have shown that teachers who believed that their students were interested in biology, that the students could relate lesson content to

everyday issues and that students had an interest in scientific thinking, learning and research used various teaching methods, techniques and instructional materials. reason behind these actions, the findings indicated

subject influenced the teacher, with active participation in the lessons also being 1999). This finding asserts

Gess-students exert a strong influence on the classroom teacher in terms of what they do lessons may have their origin in the various teaching methodologies and instructional materials used by their teachers. In order to keep student interest alive and to maintain their active participation in lessons, teachers should continue to use various teaching methods and instructional materials. These actions on behalf of teachers increase the stude

and this cycle continues setting up a virtuous circle where both sides continue to gain.

Overall, the findings highlight the importance of gaining insight into the way teachers think and act in the classroom. Although the inferences made were specific to the Turkish context and many of the specific issues may be of purely local interest (Dreyfus, Jungwirth & Tamir, 1985), the findings of this study urge us to consider the of improving instructional practices for science education (Shavelson & Stern, 1981; Munby, 1984; Pajares, 1992; Tobin, Tippins & Gallard, 1994; Czerniak, Lumpe & Haney, 1999), not just in Turkey but also in other countries. Policy capturing, i.e. simulated cases or vignettes of students, curriculum materials or teaching episodes; repertory grid technique and process tracing such as think-aloud, stimulated recall and journal keeping, questionnaires, semi-structured interviews and classroom observations (Shavelson & Stern, 1981; Clark & Peterson, 1986; Kagan, 1992; Fang, 1996) can perceptions and to gain

students was one constraint of the study. Because students are the ones who actively participate in the teaching and learning process together with teachers, their beliefs, describe the process of biology teaching. To reduce this constraint and draw rich interpretative information, student questionnaires should also be administered and classroom observations and semi-structured interviews should be conducted.

Eurasian Journal of Educational Research 29 References

Barab, S.A. & Luehmann, A.L. (2003). Building sustainable science curriculum: acknowledging and accommodating local adaptation. Science Education, 87(4), 454-467.

beliefs regarding the implementation of constructivism in their classrooms.

Journal of Science Teacher Education, 11(4), 323-343.

Calderhead, J. (1996). Teachers: beliefs and knowledge. In D.C. Berliner and R.C. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp.709-725). New York: Macmillan.

Handbook of research on teaching (pp.255-296). New York: Macmillan. curriculum reform in Texas. Science Education, 79(6), 611-635.

Cronin-implementation: Two case studies. Journal of Research on Science Teaching,

28(3), 235-250.

Czerniak, C.M

intentions to implement thematic units. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 10(2), 123-145.

Davis, K. S. (2003). Change is hard: What science teachers are telling us about reform and teacher learning of innovative practices. Science Education, 87(1), 3-30. Deemer, S.A. (2004). Classroom goal orientation in high school classrooms: revealing

links between teacher beliefs and classroom environments. Educational

Research, 46(1), 73-92.

Dindar

9(1), 123-132.

Dreyfus, A., Jungwirth, E. & Tamir, P. (1985). Biology education in Israel as viewed by the teachers. Science Education, 69(1), 83-93.

Ekici, G. (1996). Methods used by biology teachers and problems faced during instruction. Unpublished master thesis. Ankara University, Ankara.

problemler. 9, 315-330.

Fang, Z. (1996). A review of research on teacher beliefs and practices. Educational

Research, 38(1), 47-66.

Fetters, M.K., Czerniak, C.M., Fish, L. & Shawberry, J. (2002). Confronting, challenging, and changing t

change professional development program. Journal of Science Teacher

Education, 13(2), 101-130.

Gess-matter structure and its relationship to classroom practice. Journal of Research

in Science Teaching, 32(3), 301-325.

Gess-Newsome, J. (2001). The professional development of science teachers for science education reform: a review of the research. In J. Rhoton and P. Bowers